An Examination of Halloween Literature and Its Effect on The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Siriusxm and Pandora Present Halloween at Home with Music, Talk, Comedy and Entertainment Treats for All

NEWS RELEASE SiriusXM and Pandora Present Halloween at Home with Music, Talk, Comedy and Entertainment Treats For All 10/13/2020 The world is scary enough, so have some spooky fun by streaming Halloween programming on home devices & mobile apps NEW YORK, Oct. 13, 2020 /PRNewswire/ -- SiriusXM and Pandora announced today they will feature a wide variety of exclusive Halloween-themed programming on both platforms. With traditional Halloween activities aected by the Covid-19 pandemic, SiriusXM and Pandora plan to help families and listeners nd creative and safe ways to keep the spirit alive with endless hours of music and entertainment for the whole family. Beginning on October 15, SiriusXM will air extensive programming including everything from scary stories, to haunted house-inspired sounds, to Halloween-themed playlists across SiriusXM's music, talk, comedy and entertainment channels. Pandora oers a lineup of Halloween stations and playlists for the whole family, including the newly updated Halloween Party station with Modes, and a hosted playlist by Halloween-obsessed music trio LVCRFT. All programming from SiriusXM and Pandora is available to stream online on the SiriusXM and Pandora mobile apps, and at home on a wide variety of connected devices. SiriusXM's Scream Radio channel is an annual tradition for Halloween enthusiasts, providing the ultimate bone- chilling soundtrack of creepy sound eects, traditional Halloween favorite tunes, ghost stories, spooky music from classic horror lms, and more. The limited run channel will also feature a top 50 Halloween song countdown, "The Freaky 50" and will play scary score music, sound eects, spoken word stories 24 hours a day, and will set the tone for a spooktacular haunted house vibe. -

John Carpenters Tales for a Halloween Night Kindle

JOHN CARPENTERS TALES FOR A HALLOWEEN NIGHT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK John Carpenter | 96 pages | 17 Nov 2015 | Storm King Productions | 9780985325893 | English | CA, United States John Carpenters Tales For A Halloween Night PDF Book John Laughlin marked it as to-read Oct 31, Kealan Patrick Burke ,. Ana-Maria marked it as to-read Oct 18, Twists, turns, red herrings, the usual suspects: These books have it all No ratings or reviews yet No ratings or reviews yet. John Steinbeck Paperback Books. Return to Book Page. Did enjoy the one where if you killed someone you had to take over their life, like you were them. View all Our Sites. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. James rated it really liked it Jan 15, This collection of six stories has a distinct Tales from the Crypt and Creepshow vibe to it, in that we are introduced to a narrator of sorts, who is going to tell us some tales. There are three victims, two women, and one man. Average rating 3. Related Articles. Rating details. Heath , Hardcover 4. Error rating book. Make sure this is what you intended. If you get too scared, remember, it's only a comic. Brad rated it really liked it Sep 21, From John Carpenter, the man who brought you the cult classic horror film Halloween and all of the scares beyond comes the ultimate graphic novel anthology of tales to warm your toes by on a dark and stormy October night! Meg rated it really liked it Nov 07, What size image should we insert? About John Carpenter. -

John Carpenter Halloween (Original Soundtrack) Mp3, Flac, Wma

John Carpenter Halloween (Original Soundtrack) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Stage & Screen Album: Halloween (Original Soundtrack) Country: Japan Released: 1979 Style: Soundtrack, Score, Experimental, Minimal, Ambient MP3 version RAR size: 1282 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1373 mb WMA version RAR size: 1461 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 758 Other Formats: AIFF AAC DTS AHX DMF DXD APE Tracklist A1 Main Theme From "Halloween" A2 Boyfriend And Susan A3 Illinois Smith's Grove A4 Myers' House A5 At School Yard B1 Behind The Bush B2 Row 18 Lot 20 B3 Doctor And Sheriff In The Myer's House B4 Doyle Residence B5 The Night He Came Home B6 End Title Companies, etc. Made By – Nippon Columbia Co., Ltd. Credits Composed By – John Carpenter Performer – Bowling Green Jr. Philharmonic Orchestra Notes Limited pressing with "Spacesizer 360 System Recording". LP housed in poly bag, cover included OBI strip. Includes 4 page insert. Back cover states "Joy Pack Film" presents. Labels states date of August 1979 "℗ '79. 8" Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Halloween (Original John Motion Picture STV 81176 Varèse Sarabande STV 81176 US Unknown Carpenter Soundtrack) (LP, Album, Club) John Halloween (Original VSC-81176 Varèse Sarabande VSC-81176 US 1983 Carpenter Soundtrack) (Cass) Halloween (Original John Motion Picture STV 81176 Varèse Sarabande STV 81176 US 1983 Carpenter Soundtrack) (LP, Album) Halloween (Original John CL 0008 Filmmusik) (LP, Celine Records CL 0008 Germany 1989 Carpenter Album, RE) Halloween (Original John 115980 Soundtrack) (CD, Marketing-Film 115980 Germany 2003 Carpenter Album, Ltd) Comments about Halloween (Original Soundtrack) - John Carpenter Pryl Interesting...I don't think the value of the OG presses will go down though. -

Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960S and Early 1970S

TV/Series 12 | 2017 Littérature et séries télévisées/Literature and TV series Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960s and early 1970s Dennis Tredy Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/2200 DOI: 10.4000/tvseries.2200 ISSN: 2266-0909 Publisher GRIC - Groupe de recherche Identités et Cultures Electronic reference Dennis Tredy, « Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960s and early 1970s », TV/Series [Online], 12 | 2017, Online since 20 September 2017, connection on 01 May 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/2200 ; DOI : 10.4000/tvseries.2200 This text was automatically generated on 1 May 2019. TV/Series est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series o... 1 Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960s and early 1970s Dennis Tredy 1 In the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, in a somewhat failed attempt to wrestle some high ratings away from the network leader CBS, ABC would produce a spate of supernatural sitcoms, soap operas and investigative dramas, adapting and borrowing heavily from major works of Gothic literature of the nineteenth and early twentieth century. The trend began in 1964, when ABC produced the sitcom The Addams Family (1964-66), based on works of cartoonist Charles Addams, and CBS countered with its own The Munsters (CBS, 1964-66) –both satirical inversions of the American ideal sitcom family in which various monsters and freaks from Gothic literature and classic horror films form a family of misfits that somehow thrive in middle-class, suburban America. -

Redalyc.GROTESQUE REALISM, SATIRE, CARNIVAL AND

Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI E-ISSN: 1576-3420 [email protected] Sociedad Española de Estudios de la Comunicación Iberoamericana España Asensio Aróstegui, Mar GROTESQUE REALISM, SATIRE, CARNIVAL AND LAUGHTER IN SNOOTY BARONET BY WYNDHAM LEWIS Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, núm. 15, marzo, 2008, pp. 95-115 Sociedad Española de Estudios de la Comunicación Iberoamericana Madrid, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=523552801005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative REVISTA DE LA SEECI. Asensio Aróstegui, Mar (2008): Grotesque realism, satire, carnival and laughter in Snooty Baronet by Wyndham Lewis. Nº 15. Marzo. Año XII. Páginas: 95-115 ISSN: 1576-3420 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15198/seeci.2008.15.95-115 ___________________________________________________________________ GROTESQUE REALISM, SATIRE, CARNIVAL AND LAUGHTER IN SNOOTY BARONET BY WYNDHAM LEWIS REALISMO GROTESCO, LA SÁTIRA, EL CARNAVAL Y LA RISA EN SNOOTY BARONET DE WYNDHAM LEWIS AUTORA Mar Asensio Aróstegui: Profesora de la Facultad de Letras y de la Educación. Universidad de La Rioja. Logroño (España). [email protected] RESUMEN Aunque la obra del escritor británico Percy Wyndham Lewis muestra una visión satírica de la realidad, cuyas raíces se sitúan en el humor carnavalesco típico de la Edad Media y esto hace que sus novelas tengan rasgos comunes a las de otros escritores Latinoamericanos como Borges o García Márquez, la repercusión que la obra de Lewis ha tenido en los países de habla hispana es prácticamente nula. -

The Proliferation of the Grotesque in Four Novels of Nelson Algren

THE PROLIFERATION OF THE GROTESQUE IN FOUR NOVELS OF NELSON ALGREN by Barry Hamilton Maxwell B.A., University of Toronto, 1976 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department ot English ~- I - Barry Hamilton Maxwell 1986 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY August 1986 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL NAME : Barry Hamilton Maxwell DEGREE: M.A. English TITLE OF THESIS: The Pro1 iferation of the Grotesque in Four Novels of Nel son A1 gren Examining Committee: Chai rman: Dr. Chin Banerjee Dr. Jerry Zaslove Senior Supervisor - Dr. Evan Alderson External Examiner Associate Professor, Centre for the Arts Date Approved: August 6, 1986 I l~cr'ct~ygr.<~nl lu Sinnri TI-~J.;~;University tile right to lend my t Ire., i6,, pr oJcc t .or ~~ti!r\Jc~tlcr,!;;ry (Ilw tit lc! of which is shown below) to uwr '. 01 thc Simon Frasor Univer-tiity Libr-ary, and to make partial or singlc copic:; orrly for such users or. in rcsponse to a reqclest from the , l i brtlry of rllly other i111i vitl.5 i ty, Or c:! her- educational i r\.;t i tu't ion, on its own t~l1.31f or for- ono of i.ts uwr s. I furthor agroe that permissior~ for niir l tipl c copy i rig of ,111i r; wl~r'k for .;c:tr~l;rr.l y purpose; may be grdnted hy ri,cs oi tiI of i Ittuli I t ir; ~lntlc:r-(;io~dtt\at' copy in<) 01. -

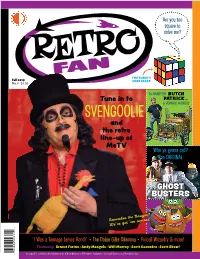

SVENGOOLIE and the Retro Line-Up of Metv Who Ya Gonna Call? the ORIGINAL

Are you too square to solve me? THE RUBIK'S Fall 2019 CUBE CRAZE No. 6 $8.95 The MUNSTERS’ BUTCH Tune in to PATRICK… & HORRIFIC HOTRODS SVENGOOLIE and the retro line-up of MeTV Who ya gonna call? The ORIGINAL GHOST BUSTERS Remember the Naugas? We’ve got ’em covered 2 2 7 3 0 0 “I Was a Teenage James Bond!” • The Dobie Gillis Dilemma • Pinball Wizardry & more! 8 5 6 2 Featuring Ernest Farino • Andy Mangels • Will Murray • Scott Saavedra • Scott Shaw! 8 Svengoolie © Weigel Broadcasting Co. Ghost Busters © Filmation. Naugas © Uniroyal Engineered Products, LLC. 1 The crazy cool culture we grew up with CONTENTS Issue #6 | Fall 2019 40 51 Columns and Special Features Departments 3 2 Retro Television Retrotorial Saturday Nights with 25 Svengoolie 10 RetroFad 11 Rubik’s Cube 3 Andy Mangels’ Retro Saturday Mornings 38 The Original Ghost Busters Retro Trivia Goldfinger 21 43 Oddball World of Scott Shaw! 40 The Naugas Too Much TV Quiz 25 59 Ernest Farino’s Retro Retro Toys Fantasmagoria Kenner’s Alien I Was a Teenage James Bond 21 74 43 Celebrity Crushes Scott Saavedra’s Secret Sanctum 75 Three Letters to Three Famous Retro Travel People Pinball Hall of Fame – Las Vegas, Nevada 51 65 Retro Interview 78 Growing Up Munster: RetroFanmail Butch Patrick 80 65 ReJECTED Will Murray’s 20th Century RetroFan fantasy cover by Panopticon Scott Saavedra The Dobie Gillis Dilemma 75 11 RetroFan™ #6, Fall 2019. Published quarterly by TwoMorrows Publishing, 10407 Bedfordtown Drive, Raleigh, NC 27614. Michael Eury, Editor-in-Chief. John Morrow, Publisher. -

Sky Pilot, How High Can You Fly - Not Even Past

Sky Pilot, How High Can You Fly - Not Even Past BOOKS FILMS & MEDIA THE PUBLIC HISTORIAN BLOG TEXAS OUR/STORIES STUDENTS ABOUT 15 MINUTE HISTORY "The past is never dead. It's not even past." William Faulkner NOT EVEN PAST Tweet 19 Like THE PUBLIC HISTORIAN Sky Pilot, How High Can You Fly by Nathan Stone Making History: Houston’s “Spirit of the Confederacy” I started going to camp in 1968. We were still just children, but we already had Vietnam to think about. The evening news was a body count. At camp, we didn’t see the news, but we listened to Eric Burdon and the Animals’ Sky Pilot while doing our beadwork with Father Pekarski. Pekarski looked like Grandpa from The Munsters. He was bald with a scowl and a growl, wearing shorts and an official camp tee shirt over his pot belly. The local legend was that at night, before going out to do his vampire thing, he would come in and mix up your beads so that the red ones were in the blue box, and the black ones were in the white box. Then, he would twist the thread on your bead loom a hundred and twenty times so that it would be impossible to work with the next day. And laugh. In fact, he was as nice a May 06, 2020 guy as you could ever want to know. More from The Public Historian BOOKS America for Americans: A History of Xenophobia in the United States by Erika Lee (2019) April 20, 2020 More Books The Munsters Back then, bead-craft might have seemed like a sort of “feminine” thing to be doing at a boys’ camp. -

Fracking (With) Post-Modernism, Or There's a Lil' Dr Frankenstein in All

1 Fracking (with) post-modernism, or there’s a lil’ Dr Frankenstein in all of us by Bryan Konefsky Since the dawn of (wo)mankind we humans have had the keen, pro-cinematic ability to assess our surroundings in ways not unlike the quick, rack focus of a movie camera. We move fluidly between close examination (a form of deconstruction) to a wide-angle view of the world (contextualizing the minutiae of our dailiness within deep philosophical inquiries about the nature of existence). To this end, one could easily infer that Dziga Vertov’s kino-eye might be a natural outgrowth of human evolution. However, we should be mindful of obvious and impetuous conclusions that seem to lead – superficially – to the necessity of a kino-prosthesis. In terms of a kino-prosthesis, the discomfort associated with a camera-less experience is understood, especially in a world where, as articulated so well by thinkers such as Sherry Turkle or Marita Sturken, one impulsively records information as proof of experience (see Turkle’s Alone Together: Why We Expect More From Technology and Less From Each Other and Sturken’s Practices of Looking: An Introduction to Visual Culture). The unsettling nature of a camera-less experience reminds me of visionary poet Lisa Gill (see her text Caput Nili), who once told me about a dream in which she and Orson Welles made a movie. The problem was that neither of them had a camera. Lisa is quick on her feet so her solution was simply to carve the movie into her arm. For Lisa, it is clear what the relationship is between a sharp blade and a camera, and the association abounds with metaphors and allusions to my understanding of the pro-cinematic human. -

THE ABSTRACT GROTESQUE in BECKETT's TRILOGY David Musgrave

THE ABSTRACT GROTESQUE IN BECKETT’S TRILOGY David Musgrave Through an examination of Beckett’s usage of the rhetorical device of the ‘enthymeme’ I try to show how the grotesque in Beckett’s Trilogy differs from previous literary examples of the mode. The article takes as its starting point Bakhtin’s periodization of the grotesque in terms of carnival culture (Rabelais) and the ‘subjective grotesque’ (Sterne) and puts forward the argument that the abstractness of Beckett’s gro- tesque is its defining feature. By positioning Beckett’s work in a gen- eral history of the grotesque, I hopefully provide a context for under- standing Beckett’s ‘modernist’ grotesque and show how it is primarily concerned with the discovery of the new. Much of the work carried out in recent years assessing Beckett’s achievements in the light of the theories of Mikhail Bakhtin has tended to focus on questions of dialogue and genre: the bedrock, in other words, of Bakhtin’s ideas that are often referred to under the rubric of ‘dialogism’. Henning’s work on Beckett and carnival, for example, works under the assumption that “Beckett shares Mikhail Bakhtin’s criticism of the repressive monologism that is so character- istic of Western thought with its penchant for abstract integrality” (Henning, 1) and proceeds to discuss some shorter works of Beckett in terms of “carnivalized dialogization” (29-31). While the Bakhtin of menippean satire is to some degree evoked, the historian of laughter and the grotesque is scarcely dealt with in this and other recent stud- ies.1 Similarly, work which focuses on the grotesque aspects of Beck- ett’s work has tended to dwell on established theories of the grotesque and has not attempted to determine how the grotesque in Beckett’s works differs from other representatives of the mode.2 My primary goal in this article is to describe how Beckett’s grotesque represents a significant development in the history of that mode. -

Fragmentary Futures: Bradbury's Illustrated Man Outlines--And Beyond

2015 Fragmentary Futures: Bradbury's Illustrated Man Outlines--and Beyond Jonathan R. Eller Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis Indianapolis, Indiana, USA IUPUI ScholarWorks This is the author’s manuscript: This article was puBlished as Eller, Jonathan R. “Fragmentary Futures: Bradbury's Illustrated Man Outlines--and Beyond” The New Ray Bradbury Review 4 (2015): 70- 85. Print. No part of this article may Be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted, or distriButed, in any form, by any means, electronic, mechanical, photographic, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Kent State University Press. For educational re-use, please contact the Copyright Clearance Center (508-744- 3350). For all other permissions, please contact Carol Heller at [email protected]. https://scholarworks.iupui.edu Fragmentary Futures: Bradbury’s Illustrated Man Outlines—and Beyond “I believe first drafts, like life and living, must be immediate, quick, passionate. By writing a draft in a day I have a story with a skin around it.” Ray Bradbury’s creative coda originated long before he fashioned this concise version of it for his December 1964 Show magazine interview. His daily writing habit had become a quotidian fever by the early 1940s, and he soon learned to avoid interruptions from any other voices—including his own rational judgments. Each day became a race between subconscious inspiration and the stifling effects of his own self-conscious thoughts—the more logical thought patterns that he desperately tried to hold at bay during the few hours it would take him to complete an initial draft. Bradbury was convinced that the magic would dissolve away if he failed to carry through on a story idea or an opening page at first sitting, and it’s not surprising that his Show interview coda came with a cautionary corollary: “If one waits overnight to finish a story, quite often the texture one gets the next day is different. -

Passages Taken from Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World

Passages taken from Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World. Trans. by Helene Iswolsky. Bloomington: Indiana University Press (1984). For a fuller understanding of Bakhtin's work one should read the work in full, but I hope the following will serve to introduce Bakhtin's concepts to beginning students of renaisance drama. Page numbers after particular passages refer the reader to the book. "Bakhtin's carnival, surely the most productive concept in this book, is not only not an impediment to revolutionary change, it is revolution itself. Carnival must not be confused with mere holiday or, least of all, with self-serving festivals fostered by governments, secular or theocratic. The sanction for carnival derives ultimately not from a calendar prescribed by church or state, but from a force that preexists priests and kings and to whose superior power they are actually deferring when they appear to be licensing carnival." (Michael Holquist, "Prologue," Rabelais and His World, xviii) From the "Introduction" "The aim of the present introduction is to pose the problem presented by the culture of folk humor in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance and to offer a description of its original traits. "Laughter and its forms represent... the least scrutinized sphere of the people's creation.... The element of laughter was accorded to the least place of all in the vast literature devoted to myth, to folk lyrics, and to epics. Even more unfortunate was the fact that the peculiar nature of the people's laughter was completely distorted; entirely alien notions and concepts of humor, formed within the framework of bourgeois modern culture and aesthetics, were applied to this interpretation.