Modernity in Architecture in Relation to Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unity in Diversity Pic

e SUNDAY FEBRUARY 7, 2021 TIMES COMPETITIONS PAGE 2 LANDMARKS PAGE 3 follow us on Unity in Diversity Pic. by Nilan Maligaspe www.fundaytimes.lk 2 TIMES Please send Across Down competition entries to: Junior Crossword – No. 954 1 A spring flower 1 Risky Funday Times 6 Tidy 2 A special grand C/O the Sunday Times 7 Sitting down meal for lots of P.O. Box 1136, Colombo. 9 Go in people Or 11 Robber 3 Student’s table 8, Hunupitiya Cross Road, 12 Frequently 4 Some shoes are Colombo 2. 13 Have a quarrel made of this Please note that competition 16 Hit 5 Female deer entries (except Reeves Art) 18 A married 8 Not the same are accepted by email. partner 10 The late part of Please write the name of the 19 A shoot-out the day competition and the date clearly 14 Departing at the top of your entry and include 15 Stitched the following details: 17 A metal Full Name (including Surname), Date of Birth, Address, Telephone No. and School. TIMES Please underline the name most commonly used. Solution - No. 952 All competition entries should be Please enter your full name, certified by a parent or guardian date of birth, home address, as your own work. mobile number and school. Competition entries without the full details requested above, All entries must be will be disqualified. certified Closing date by a teacher or parent Amaan Morris, for weekly competitions: as your own work. Colombo 7 February 24, 2021 Telephone: 2479337/2479333 Email: [email protected] Age: 10 – 12 years Age: 13 – 15 years Word Count: 150 – 200 Word Count: 200 – 250 Topic: Sri Lanka’s National Flag Some national heroes super Topic: who worked towards Diary of a Wimpy Kid – Independence of the country. -

This Paper Examines Regionalist Interpretations of the Work of the Late Geoffrey Bawa, Sri Lanka's Most Celebrated Architect

The Politics of Culture and the Problem of Tradition: Re-evaluating Regionalist Interpretations of the Architecture of Geoffrey Bawa Carl O'Coill and Kathleen Watt University of Lincoln, United Kingdom Introduction This paper examines regionalist interpretations of the work of the late Geoffrey Bawa, Sri Lanka's most celebrated architect. After a brief period practising law, Bawa turned his love of buildings and gardens into an exceptional 45-year career in architecture, gaining widespread international recognition. The architecture that emerged from Bawa's practice in Colombo has been termed 'eclectic' and is said to reflect the varied backgrounds of the artists and designers with whom he worked. Although sometimes labelled a 'romantic vernacularist' or 'tropical modernist', Bawa is best known as a 'regionalist' because of the way he attempted to blend local building traditions with modernist aspirations. The aim of this paper is to re-evaluate Bawa's architecture as an example of 'regionalism' and show how regionalist interpretations of his work have been constrained by a form of dualistic thinking that has its foundations in the ideology of Western modernity. In their preoccupation with the modern/traditional dichotomy, we argue, critics have failed to acknowledge the extent to which his work is bound up with local struggles over identity in the context of a long-standing and violent ethnic conflict in Sri Lanka. Our intention here is not to tarnish Bawa’s well-deserved reputation, but to reveal alternative readings of his architecture from outside the canon of critical regionalism to demonstrate the fundamental inadequacies of this perspective.1 Regionalism 'Regionalism' is a slippery term and there is no clear consensus about its meaning, however, many authors have acknowledged that debates about regionalism in architecture are united by a common concern with the 'problem' of tradition. -

Buddha to Krishna

BUDDHA TO KRISHNA This book traces the emergence of modernism in art in South Asia by exploring the work of the iconic artist George Keyt. Closely interwoven with his life, Keyt’s art reflects the struggle and triumph of an artist with very little support or infrastructure. He painted as he lived: full of colour, turmoil and intensity. In this compelling account, the author examines the eventful course of Keyt’s journey, bringing to light unknown and star- tling facts: the personal ferment that Keyt went through because of his tumultuous relationships with women; his close involvement with social events in India and Sri Lanka on the threshold of Independence; and his somewhat angular engagement with artists of the ’43 Group. A collector’s delight, including colour plates and black and white pho- tographs, reminiscences and intimate correspondences, this book reveals the portrait of an artist among the most charismatic figures of our time. This book will be of interest to scholars and researchers of art and art history, modern South Asian studies, sociology, cultural studies as well as art aficionados. Yashodhara Dalmia is an art historian and independent curator based in New Delhi, India. She has written several books including Amrita Sher- Gil: A Life (2006) that have received widespread international acclaim. She is also the author of The Making of Modern Indian Art: The Progressives (2001) and Journeys: Four Generations of Indian Artists (2011). She has curated many art shows, with the most recent being the centenary show ‘Amrita Sher-Gil: The Passionate Quest’ at the National Gallery of Mod- ern Art in New Delhi, Mumbai and Bengaluru in 2014. -

Aitken Spence Newsletter

MONTHLY NEWSLETTER JANUARY 2020 EXPLORE Awe-inspiring sights, sounds and sensations at Heritance Kandalama Heritance Kandalama is widely considered an architectural masterpiece and an eco-resort unlike any other. Adding to this allure is the hotel's idyllic location, which overlooks the world’s eighth wonder. The first thing you notice about the hotel is how it rises majestically alongside the face of a cliff and is engulfed by a canopy of tropical vegetation. This makes for a lush, panoramic setting, and a truly enchanting destination. The property's award winning design is a testament to the prowess of architect Geoffrey Bawa and the Company's vision towards sustainability. With a large number of accolades, recognition and certifications, Heritance Kandalama has been a trendsetter in hospitality, culinary excellence, service superiority and continues to make waves through its unique value propositions. Escape to your own private island with Adaaran Select Hudhuran Fushi, Maldives Adaaran Select Hudhuran Fushi is set amidst 83 sprawling acres of lush tropical beach property neighbouring the pristine Kani Beach on the enchanting Lohifushi Island. An atoll which richly deserves its title as the isle of white gold. The resorts unique design lets it blend into the tropical wilderness that surrounds it, making it one of the most aesthetically appealing resorts in the Maldives. This meticulous attention to detail extends to every facet of the resort, from the exquisite villas each offering a variety of settings, to the scrumptious gastronomy, endless excursions, and exhilarating activities. There are also endless options for rest and relaxation, including a spa that offers world-class therapy, accompanied by signature service that is always on call, ready to satisfy your every need. -

The Jewels of Sri Lanka with Dick Bradford

The Jewels of Sri Lanka with Dick Bradford 4th – 17th February 2018 The Ultimate Travel Company Escorted Tours Gal Vihara, Polonnaruwa The Jewels of Sri Lanka With Dick Bradford 4th – 17th February 2018 Contact Flora Scott-Williams Direct Line 020 7386 4643 Telephone 020 7386 4620 Fax 020 7386 8652 Email [email protected] Dick Bradford During his service in the Army Dick lived with his wife Anne and their children in various countries of South East Asia. He has recently retired from his second career as a land manager. He is an enthusiastic and experienced world traveller with a particular interest in the cultures, customs and food of the East. Anne’s cousin, David Swannell is the owner of the Ashburnham Estate which we will visit. Dick’s late sister, Julia was a travel consultant with The Ultimate Travel Company from its inception and was well known by many clients. Detailed Itinerary The beautiful island of Sri Lanka, with its ancient past, colonial tradition, spectacular scenery and lush tropical jungle, will enchant everybody, and this tour is a fascinating introduction to this very special country. It encompasses impressive rock-hewn fortresses, magnificent second and third century BC temples - many UNESCO World Heritage Sites - ethereal religious sites and ruined cities, botanical gardens, wildlife sanctuaries, tea plantations and an unspoiled Victorian hill station. Our journey begins in the capital city of Colombo, from which we head inland to Habarana to explore the cultural triangle. We see Sigiriya, an impressive rock-hewn fortress, and the beautifully preserved remains of the 11th century capital, Polonnaruwa. -

The Architecture of Geoffrey Bawa an Illustrated Presentation by Architect Thomas Soper, AIA Sunday, June 19, 2016, 2 P.M

SACHI in collaboration with Palo Alto Art Center is delighted to present An illuminating discussion on Sri Lankan Architect Geoffrey Bawa Portal to Sri Lankan Culture: The Architecture of Geoffrey Bawa An Illustrated Presentation by Architect Thomas Soper, AIA Sunday, June 19, 2016, 2 p.m. Palo Alto Art Center | 1313 Newell Road, Palo Alto Rsvp recommended, [email protected]; Tel. 650-918-6335 Geoffrey Bawa (1919-2003) is Sri Lanka's and one of Asia's most celebrated and influential architects of the 20th century. Bawa received the Aga Khan Special Award for a Lifetime's Achievement in Architecture in 2001. His life, work, and legacy have had a tremendous impact on emerging architects in the regions of Asia. In describing the essence of Bawa's work, Sri Lankan architect, Channa Daswatte, Geoffrey Bawa's protege, sums up his mentor's ennobling vision: "Architecture is seen as a line that defines and marks the presence of man in the landscape and then dissolves into the background to make way for life." Mr. Soper's objective is to present Geoffrey Bawa's inspiring vision as a world Architect. He will elaborate on some of Bawa's key projects to demonstrate his mastery of regional splendor, providing insight into Sri Lankan culture via his art form. Mr. Soper traveled to Sri Lanka in 2007, and continues to explore Bawa's architecture with great fascination. Kandalama Hotel , Dambulla 1991-4 | photography by Thomas Soper Thomas Soper is a practicing architect working in and from the Bay Area for the past four decades. -

Splendid Sri Lanka

SPLENDID SRI LANKA Small Group Trip 12 Days ATJ.com | [email protected] | 800.642.2742 Page 1 Splendid Sri Lanka SPLENDID SRI LANKA Small Group Trip 12 Days SRI LANKA Minneriya National. Park Polonnaruwa Sigiriya .. Dambulla . Kandalama . Kandy Negombo . Colombo Nuwara Eliya . Yala National Park . Galle . UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE SITES, ROCK ART, WILDLIFE SAFARIS, COUNTRY TRAIN RIDES, NATURE WALKS, THE ESALA PERAHERA FESTIVAL, GORGEOUS INDULGE YOUR ACCOMMODATIONS WANDERLUST Perched like a precious pearl below the “ear of India” in the Indian Ocean, Sri Lanka is Ø Experience the spectacular Esala Perahera festival an island awash in cultural wealth and natural beauty, whose inhabitants compare their land to the alongside locals Garden of Eden. A stunning mix of mountains, jungles and beaches, it is dotted with the ruins of Ø Search for Sri Lanka’s elusive leopard and other spectacular palaces and shrines. fauna on 4WD wildlife safaris Over the centuries, Sri Lanka has welcomed a variety of influences that have uniquely shaped Ø Explore the historic Galle Fort with a fourth- its culture. These included Hindu invaders from the north, Arab and the Dutch spice traders, Portuguese missionaries and the English in their quest for tea, regional hegemony and lush, generation local as your guide cool hill stations. These visitors all left their mark atop the ancient veneer of vibrant Sinhalese Ø Sip tea and nibble scones at British-tinged hill civilization, which peaked around 1,000 years ago, leaving a plethora of rich archaeology sites in stations amid rolling tea plantations its wake. Ø Converse with a wildlife biologist who has been On this definitive journey, delve deep into Sri Lanka’s contrasting landscapes, cultural treasures studying Sri Lankan primates for decades and national parks teeming with wildlife. -

Sri Lanka: Colours & Flavours 4 – 18 September 2020

SRI LANKA: COLOURS & FLAVOURS 4 – 18 SEPTEMBER 2020 FROM £4,895 PER PERSON Tour Leaders: Chris and Carolyn Caldicott SPECTACULAR SCENERY, COLONIAL HISTORY AND RICH CULLINARY TRADITIONS Join us on this off the beaten track journey to the teardrop island of Sri Lanka and discover the rich culinary traditions, cultural diversity and atmospheric historic towns of this lush tropical island with a backdrop of extraordinarily beautiful landscapes of misty hills, verdant forests and palm fringed beaches. The journey begins in the dynamic Indian Ocean port of Colombo where we will stay in a charming colonial era villa and explore the thriving street markets, ancient Buddhist temples and the contemporary cool café and shopping scene. Travelling inland by rail, a feat of 19th century British imperial railway construction that offers a nostalgia packed train ride from the steamy jungles of the coast to the colonial era hill stations of tea country, we will explore the island’s interior staying in a boutique plantation house of a working tea estate. From an eco-jungle lodge in the wilderness of Gal Oya National Park we will walk with indigenous Vedda people to a forest waterfall for sundowners and take a boat safari in search of swimming elephants. Sitting in God’s Forest stylish Koslanda will be our base for forest treks to find wild coffee, pepper vines and cinnamon and culinary adventures into local cuisine between visiting the largest rock cut Buddha statues on the island and the dizzy heights and spectacular views of Lipton’s Seat. Back on the coast the Galle Fort is packed with remnants of a vibrant past that lured spice merchants from around the globe for centuries alongside chic café society in beautifully restored villas. -

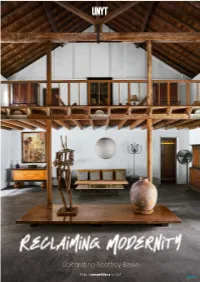

Celebrating Geoffrey Bawa

Celebrating Geoffrey Bawa https://competitions.uni.xyz https://competitions.uni.xyz Source Img 1: The Horagalla Home Source Premise Emphasising on the lack of ornamentation and the clarity in function, structural innovation and choice of materials, modernism emerged in the early years of the 20th century in response to the drastic developments in technologies and social circumstances. Adapting this to the tropics, meant a greater focus on context and climate - local materials, technique, art and the warm humid climate. Offering an alternative to international modernism, Tropical or regional modernism demonstrated that architecture could reflect context, tradition and time. https://competitions.uni.xyz 2 Img 3: Lunuganga, Bawa’s Garden Source Backstory In India, Sri Lanka, the Middle East, Africa, and the Caribbean, Brazil, and Mexico; Tropical Modernism rose as a response to colonial architecture as a negation of local tradition, and context, which was known for its formal symmetrical style with a disregard for local technique and craft. Let's have a closer look at Sri Lanka. Humble, aesthetic and radical, Tropical Modernism in Sri Lanka manages to reflect the country's traditional, cultural, and historical resources without rejecting new technological influences from the West, while engaging with broader cultural and political questions. Considered to be one of Sri Lanka's foremost architects, Geoffrey Bawa is credited to be one the founding fathers of Tropical Modernism. https://competitions.uni.xyz 3 Img 4: The Neptune Hotel (now the Heritance Ayurveda at Beruwala) Source Brief Leaving an everlasting mark on Sri Lanka's built landscape, Geoffrey Bawa's designs establish an unique, recognizable style of design inspiring architects across the world; referencing local conditions while allowing for a modern lifestyle. -

Voluptuous Maidens and Cubist Demons: the "War of Mara" Panel of George Keyt's

VOLUPTUOUS MAIDENS AND CUBIST DEMONS: THE "WAR OF MARA" PANEL OF GEORGE KEYT'S MURALS AT GOTAMI VIHARA, BORELLA, SRI LANKA I 2 Sometime before 1937 , George Keyt wrote the following lines of verse: The desired image continues to subsist on absence, Continues to subsist in me, And presents a masquerade of itself, An assumption of itself, Many moods and sources of its face and voice in things not visible, The breath of feelings which hasten across my path, The contemplation of a shadow. But is it no cause for alarm that returning That shape will find itself a stranger among the emanations') I shall spare the work of absence, The hidden images, the twisted longings ecstatic in entanglement, Desires fading into foliage, The hidden images, the happiness in everlasting retreat from the fear of revelation.3 Prior to the 1930s Keyt had long abandoned his Christian up-bringing and enjoyed his own Buddhist revival." During the 1930s he had begun the process of divorce I This essay is the result of work begun for Professors Jane Daggett Dillenberger and Doug Adams (1947-2007) as part of 'The Devil and Soul in Art and Theology" at the Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, California. The author wishes to acknowledge their support, enthusiasm and pioneering life work in the field of art and religion with deepest admiration and gratitude. The author also thanks Mr. LSD. Pieris of the Sapumal Foundation for readily allowing "Still Life with Mangoes" which is part of the holdings of the Foundation to be reproduced in the journal; Mr. -

Bibli 29.7.99

Geoffrey Bawa Bibliography American Institute of Architects. "Quietly monumental parliament in the new capital city". Architecture. USA: Sept., 1984. American Institute of Architects. "Gracefully horizontal university buildings overlooking the sea". Architecture. USA: Sept., 1988. Anjalendran, C. "Current Architecture in Sri Lanka". Mimar, no. 42. March, 1992. Anjalendran, C. & Channa Daswatte. "Recent Architecture in Sri Lanka: 1991-93". Architecture + Design, vol. xi, no. 4. July/Aug., 1994. Anjalendran, C & Rajiv Wanasundera. "Trends and Transitions - A review of styles and influences on the built form in Sri Lanka, 1940-1990". Architecture + Design. vol. vii, no. 2, March/April, 1990a. Bawa, Geoffrey. "A Way of Building". Times of Ceylon Annual. Colombo: 1968. Bawa, Geoffrey. "Ceylon a Philosophy for Building". Architects' Journal. 15 Oct., 1969. Bawa, Geoffrey. "My Architecture". ARCASIA Forum Conference, Bali, 24 October 1987. Hong Kong: Architect Asia Publications, August, 1988. Bawa, Geoffrey. "The Eighties". Architecture and Design. vol. vii, no.2, March/April, 1990. Bawa, Geoffrey & Ulrik Plesner. "Gamle Bygninger pa Ceylon". Arkitekten. no. 16, 1965a. Bawa, Geoffrey & Ulrik Plesner. "Arbejder pa Ceylon". Arkitekten. no.17, 1965b. Bawa, Geoffrey & Ulrik Plesner. "Ceylon - Seven New Buildings". Architectural Review. February 1966a. Bawa, Geoffrey & Ulrik Plesner . "The Traditional Architecture of Ceylon". Architectural Review. February 1966b. Bawa, Geoffrey, Christoph Bon & Dominic Sansoni. Lunuganga. Singapore: Times Editions, 1990. Brawne, Michael. "The Work of Geoffrey Bawa". Architectural Review. April 1978. Brawne, Michael. "The University of Ruhuna". Architectural Review. Nov., 1986. Brawne, Michael. From Idea to Building. London: Butterworth Heinemann, 1992. Brawne, Michael. "Paradise Found". Architectural Review. Dec., 1995. Brawne, Michael. “Bawa Beatified” (review), Architectural Review, June 2003 Bryant, Lynne. -

Heritage Tour to Sri Lanka Medical, Military and Cultural Histories 15 – 29 April 2021

Sigiriya Citadel Heritage Tour to Sri Lanka Medical, Military and Cultural Histories 15 – 29 April 2021 With Galle Extension 15 April – 2 May 2021 Elephants in Habarana Welcome to Sri Lanka, a small island Next day drive to Habarana in the ancient crammed full of treasures, with no fewer cultural triangle of the island. Arrive in Habarana than eight UNESCO World Heritage Sites. and check into the lovely Cinnamon Lodge. It offers mystical ruins, jungles, gleaming Spend the rest of the day at leisure or take white tropical beaches, national parks with options to visit the spa or take a short nature huge herds of elephants and mouthwatering and wildlife trek of the area before dinner. cuisine. Its seas are home to dolphins, turtles and the largest colony of blue whales on the Next day head out to the legendary sky citadel planet. of Sigiriya, possibly the most spectacular site in Sri Lanka. Built in the 5th century on top On this heritage tour you will travel from of a vast 200m granite rock, the rock fortress the colonial capital, Colombo, to the ancient is famous for its ‘Lion Rock’ and its ‘Celestial cultural heartland of the island, through Maidens’ frescoes. Climb up in the cool early jungles to the coast at Trincomalee and into morning for spectacular jungle views. After the highlands of Nuwara Eliya. Along the descending, visit a nearby village and its school way there is a wide range of visits providing before enjoying a typical Sri Lankan lunch. real insight into Sri Lankan history and society as well as ample free time to relax or explore at your own pace.