Dempsey Proof December.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

87 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

87 bus time schedule & line map 87 Kalupur Terminus - Chandkheda View In Website Mode The 87 bus line (Kalupur Terminus - Chandkheda) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Chandkheda: 6:40 AM - 9:30 PM (2) Kalupur Terminus: 7:50 AM - 10:40 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 87 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 87 bus arriving. Direction: Chandkheda 87 bus Time Schedule 26 stops Chandkheda Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 6:40 AM - 9:30 PM Monday 6:40 AM - 9:30 PM Maninagar Maninagar Railway Station, Ahmadābād Tuesday 6:40 AM - 9:30 PM Jawahar Chowk Wednesday 6:40 AM - 9:30 PM Bhairavnath Thursday 6:40 AM - 9:30 PM Friday 6:40 AM - 9:30 PM Sah Alam Darwaja Saturday 6:40 AM - 9:30 PM S. T. Stand Kamnath Mahadev / Raipur Darwaja Sarangpur 87 bus Info Direction: Chandkheda Kalupur Stops: 26 Trip Duration: 47 min Naroda Road, Ahmadābād Line Summary: Maninagar, Jawahar Chowk, Prem Darwaja Bhairavnath, Sah Alam Darwaja, S. T. Stand, Kamnath Mahadev / Raipur Darwaja, Sarangpur, Kalupur, Prem Darwaja, Dariyapur Darwaja, Delhi Dariyapur Darwaja Darwaja, Income Tax O∆ce, Usmanpura, Vadaj Bus Terminuss, Subhash Bridge, Keshav Nagar, Delhi Darwaja Dharmanagar, Ram Nagar, Chintamani Society, Abu Koba Cross Road, Gujarat Stadium, Motera Gam, Income Tax O∆ce Government Engineering College, Santokba Hospital, Shivshakti Nagar, Chandkheda Usmanpura Vadaj Bus Terminuss Subhash Bridge Keshav Nagar Dharmanagar Ram Nagar Chintamani Society Abu Koba Cross Road Ram Bag Road, Ahmadābād Gujarat Stadium -

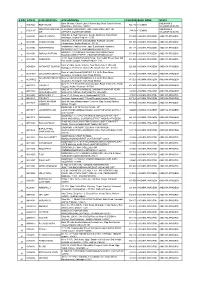

State Zone Commissionerate Name Division Name Range Name

Commissionerate State Zone Division Name Range Name Range Jurisdiction Name Gujarat Ahmedabad Ahmedabad South Rakhial Range I On the northern side the jurisdiction extends upto and inclusive of Ajaji-ni-Canal, Khodani Muvadi, Ringlu-ni-Muvadi and Badodara Village of Daskroi Taluka. It extends Undrel, Bhavda, Bakrol-Bujrang, Susserny, Ketrod, Vastral, Vadod of Daskroi Taluka and including the area to the south of Ahmedabad-Zalod Highway. On southern side it extends upto Gomtipur Jhulta Minars, Rasta Amraiwadi road from its intersection with Narol-Naroda Highway towards east. On the western side it extend upto Gomtipur road, Sukhramnagar road except Gomtipur area including textile mills viz. Ahmedabad New Cotton Mills, Mihir Textiles, Ashima Denims & Bharat Suryodaya(closed). Gujarat Ahmedabad Ahmedabad South Rakhial Range II On the northern side of this range extends upto the road from Udyognagar Post Office to Viratnagar (excluding Viratnagar) Narol-Naroda Highway (Soni ni Chawl) upto Mehta Petrol Pump at Rakhial Odhav Road. From Malaksaban Stadium and railway crossing Lal Bahadur Shashtri Marg upto Mehta Petrol Pump on Rakhial-Odhav. On the eastern side it extends from Mehta Petrol Pump to opposite of Sukhramnagar at Khandubhai Desai Marg. On Southern side it excludes upto Narol-Naroda Highway from its crossing by Odhav Road to Rajdeep Society. On the southern side it extends upto kulcha road from Rajdeep Society to Nagarvel Hanuman upto Gomtipur Road(excluding Gomtipur Village) from opposite side of Khandubhai Marg. Jurisdiction of this range including seven Mills viz. Anil Synthetics, New Rajpur Mills, Monogram Mills, Vivekananda Mill, Soma Textile Mills, Ajit Mills and Marsdan Spinning Mills. -

Sabarmati Riverfront Development Project

SABARMATI RIVERFRONT DEVELOPMENT PROJECT A Multidimensional Environmental Improvement and Urban Rejuvenation Project … one of the most innovative projects towards urban regeneration in the world to make the city livable & sustainable (KPMG ) SABARMATI RIVER and AHMEDABAD The River Sabarmati flows from north to south splitting Ahmedabad into almost two equal parts. For many years, it has served as a water source and provided almost no formal recreational space for the city. As the city has grown, the Sabarmati river had been abused and neglected and with the increased pollution was posing a major health and environmental hazard to the city. The slums on the riverbank were disastrously flood prone and lack basic infrastructure services. The River became back of the City and inaccessible to the public Ahmedabad and the Sabarmati :1672 Sabarmati and the Growth of Ahmedabad Sabarmati has always been important to Ahmedabad As a source for drinking water As a place for recreation As a place to gather Place for the poor to build their hutments Place for washing and drying clothes Place for holding the traditional Market And yet, Sabarmati was abused and neglected Sabarmati became a place Abuse of the River to dump garbage • Due to increase in urban pressures, carrying capacity of existing sewage system falling short and its diversion into storm water system releasing sewage into the River. Storm water drains spewed untreated sewage into the river • Illegal sewage connections in the storm water drains • Open defecation from the near by human settlements spread over the entire length. • Discharge of industrial effluent through Nallas brought sewage into some SWDs. -

(To Be Published in the Gazette of India, Part-II, and Section 3, Sub

Form 1 Application for Environmental Clearance Under EIA Notification, 2006 (amended) for settting up Mandal Becharaji Special Investment Region In two clusters at Mandal, Detroj Taluka of Ahmedabad District and Becharaji, Bechraji Taluka of Mehsana District Gujarat M/s Mandal Becharaji Special Investment Region Development Authority Block No. 1-2, 3rd Floor, Udyog Bhavan, Gandhinagar - 382017, Gujarat May 2018 Form 1 Proposed Mandal Becharaji Special Investment Region in Ahmedabad and Mehsana District, Gujarat ============================================================================================================ FORM 1 (I) Basic Information: Item Details S.No. 1 Name of the project/s: Mandal Becharaji Special Investment Region 2 S. No. in the schedule large industrial park/areas (schedule 7 (c )) Common Effluent Treatment Plant (schedule 7(h)) Common Municipal Solid Waste Management Facility (schedule 7(i)) Area Development projects (schedule 8(b) 3. Proposed Total area: 10200 ha (102 sq.km) capacity/area/length/tonnage Two clusters: to be handled/command Cluster A - approx. 5060 ha (revenue lands of 3 villages, area/lease area/number of wells falling in Ahmedabad and Mehsana districts) to be drilled. Cluster B - approx. 5150 ha (revenue lands of 5 villages, falling in Ahmedabad district) Annex I - list of villages under SIR Notification 4. New/Expansion/Modernization New 5. Existing Capacity Area etc. Not applicable 6. Category of Project i.e.' A' or 'B' Category – A 7. Does it attract the general No condition? If yes, Please -

SRFDCL Presentation

Sabarmati Riverfront Reconnecting Ahmedabad to its River Sabarmati Riverfront A Catalyst for Ahmedabad’s Economic Growth Sabarmati Riverfront Reconnecting Ahmedabad to its River Urbanization is the defining phenomenon of the 21st century Globally, an unprecedented Pace & Scale of Urbanization Sabarmati Riverfront Reconnecting Ahmedabad to its River For the first time in history, more than half of the world’s population lives in cities 90% of urban growth is taking place in the developing world UN World Population Prospects: The 2006 Revision and World Urbanization Prospects Cities are Engines of Economic Growth •Economic growth is associated with Sabarmati Riverfront Reconnecting Ahmedabad to its River agglomeration • No advanced country has achieved high levels of development w/o urbanizing •Density is crucial for efficiency in service delivery and key to attracting investments due to market size •Urbanization contributes to poverty reduction UN World Population Prospects: The 2006 Revision and World Urbanization Prospects Transformational Urbanism Sabarmati Riverfront Reconnecting Ahmedabad to its River 1. The logic of economic geography 2. Well-planned urban development – a pillar of economic growth Sabarmati Riverfront Reconnecting Ahmedabad to its River Living close to work can encourage people to walk and cycle or use public transport. Makes the private vehicle less popular. Makes the city healthy Advantage Gujarat Sabarmati Riverfront Reconnecting Ahmedabad to its River 6% of India’s Geographical 5% of India’s population: Area: -

Project Topic:- “Mode Choice Between Roadway and Waterway”

Project Topic:- “Mode choice between Roadway and Waterway” Content… • Introduction • Objective • Literature review • Methodology • Study area map • Various survey • Analysis of survey • Over view of sabarmati riverfront, Ahmedabad • Research paper for waterway • Conclusion • References Introduction •. Roadway and waterway are plays an important role in our country’s society and economy as well as in our multi-modal transportation system. Its low expenses and high accessibility, as compared with other alternatives, amplifies a great demand for carrying goods and passengers within the country. • The main objective of this study is to introduce non- conventional mode of transportation at urban level and reduce environmental impacts , traffic congestion, traffic delay and large traffic emissions at urban level by introducing alternative mode of transportation. • Selection of route for water transportation is from Subhas bridge circle to paldi circle and carrying out the analysis for the route. Continue…. • Comparing the distance, time and feasibility for the water transportation to the various other modes of transportation and mass transportation in the Ahmedabad city. • Carrying out the study for the social, economical and environmental impacts related with the various modes of transportation and comparing them. In this study main three types of survey we are doing and its shown below: 1) Traffic volume count 2) Origin and destination (O-D) survey 3) Speed survey Characteristics of Urban Transportation Modes: • Efficiency • Air Pollution • Noise Pollution • Climate Change • Aesthetic Values • Vulnerability of Transport Modes and Systems • Sustainability of the Modes and the System • Accidents Objectives 1. To introduce non-conventional mode of transportation at urban level. 2. To reduce environmental impacts , traffic congestion, traffic delay and large traffic emissions at urban level by introducing alternative mode of transportation. -

MERCHANT STORE ADDRESS CITY STATE NAME BHARTI AIRTEL SER Airtel Lobby, Zodiac House Ground Floor, Off Sg Highway AHMEDABAD Gujar

MERCHANT STORE ADDRESS CITY STATE_NAME BHARTI AIRTEL SER Airtel Lobby, Zodiac House Ground Floor, Off Sg Highway AHMEDABAD Gujarat Samsung Mobile 59, Jay Ambe Complex , Bavla AHMEDABAD Gujarat Samsung Mobile 12- Arth Complex Apna Cinema Station Road Sanand AHMEDABAD Gujarat JIYA SALES Madhuvan Shopping Center,Opp. Shivbhula Hall, Dholka Road, Bavla AHMEDABAD Gujarat BHARTI AIRTEL SER GF,6 Aaron Elegance Opp. Radhe Bungalow-1 New CG road, Chandkheda AHMEDABAD Gujarat Vijay Sales R 3, The Mall,2 Ed Floor, AHMEDABAD Gujarat HOTSPOT SALES N SOL PVT LTD Shop No.8,Devarc Mall, Iscon Cross Road, S G Highway Near Croma AHMEDABAD Gujarat HOTSPOT SALES N SOL PVT LTD Shop No 8, Balaji Centre, Drive in Road, Memnagar AHMEDABAD Gujarat Reliance Retail Arved Transcube Plaza,Unit No.46 Ground Floor Unit No.30 Fi Subhash Bridge Bus Terminal AHMEDABAD Gujarat Samsung Mobile 303, Sunrise Avenue, Opp Vedant Hospital, Stadium Commerce Road, Navrangpura AHMEDABAD Gujarat Infiniti Retail Ratna Business Sqr, Final Plot No 485 Tp Scheme No 3, Opp Hk College AHMEDABAD Gujarat Infiniti Retail Himalaya Mall, Near Indraprasth Tower, AHMEDABAD Gujarat Reliance Retail Shyam Shikhar Complex, India Colony Cross Road, Bapunagar AHMEDABAD Gujarat Reliance Retail Shop No. 1,2,3, 100Ft Road, Prahlad Nagar,Anand Nagar, AHMEDABAD Gujarat Reliance Retail Sangath Mall, Opp Eng College, Chandkheda Gandhinagar Highway, Sabarmati AHMEDABAD Gujarat Reliance Retail Opp Navarangpura Police Station , Opp Naptune House, High Street, Shrimali Society AHMEDABAD Gujarat Reliance Retail Drive In Store , Near Drive In Cinema,Fp No.-05Sub Plot No-5/1,Tp No.-1/A, AHMEDABAD Gujarat Samsung Mobile C-008/9/9A, Supath-2 Complex,Nr. -

Why India /Why Gujarat/ Why Ahmedabad/ Why Joint Care Arthroscopy Center ? Why India ? Medical Tourism in India Has Witnessed Strong Growth in Past Few Years

Why India /Why Gujarat/ Why Ahmedabad/ Why Joint Care Arthroscopy Center ? Why India ? Medical Tourism in India has witnessed strong growth in past few years. India is emerging as a preferred destination for international patients due to availability of best in class treatment at fraction of a cost compared to treatment cost in US or Europe. Hospitals here have focused its efforts towards being a world-class that exceeds the expectations of its international patients on all counts, be it quality of healthcare or other support services such as travel and stay. Why Gujarat ? With world class health facilities, zero waiting time and most importantly one tenth of medical costs spent in the US or UK, Gujarat is becoming the preferred medical tourist destination and also matching the services available in Delhi, Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh. Gujarat spearheads the Indian march for the “Global Economic Super Power” status with access to all Major Countries like USA, UK, African countries, Australia, China, Japan, Korea and Gulf Countries etc. Gujarat is in the forefront of Health care in the country. Prosperity with Safety and security are distinct features of This state in India. According to a rough estimate, about 1,200 to 1,500 NRI's, NRG's and a small percentage of foreigners come every year for different medical treatments For The state has various advantages and the large NRG population living in the UK and USA is one of the major ones. Out of the 20 million-plus Indians spread across the globe, Gujarati's boasts 6 million, which is around 30 per cent of the total NRI population. -

S No Atm Id Atm Location Atm Address Pincode Bank

S NO ATM ID ATM LOCATION ATM ADDRESS PINCODE BANK ZONE STATE Bank Of India, Church Lane, Phoenix Bay, Near Carmel School, ANDAMAN & ACE9022 PORT BLAIR 744 101 CHENNAI 1 Ward No.6, Port Blair - 744101 NICOBAR ISLANDS DOLYGUNJ,PORTBL ATR ROAD, PHARGOAN, DOLYGUNJ POST,OPP TO ANDAMAN & CCE8137 744103 CHENNAI 2 AIR AIRPORT, SOUTH ANDAMAN NICOBAR ISLANDS Shop No :2, Near Sai Xerox, Beside Medinova, Rajiv Road, AAX8001 ANANTHAPURA 515 001 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 3 Anathapur, Andhra Pradesh - 5155 Shop No 2, Ammanna Setty Building, Kothavur Junction, ACV8001 CHODAVARAM 531 036 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 4 Chodavaram, Andhra Pradesh - 53136 kiranashop 5 road junction ,opp. Sudarshana mandiram, ACV8002 NARSIPATNAM 531 116 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 5 Narsipatnam 531116 visakhapatnam (dist)-531116 DO.NO 11-183,GOPALA PATNAM, MAIN ROAD NEAR ACV8003 GOPALA PATNAM 530 047 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 6 NOOKALAMMA TEMPLE, VISAKHAPATNAM-530047 4-493, Near Bharat Petroliam Pump, Koti Reddy Street, Near Old ACY8001 CUDDAPPA 516 001 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 7 Bus stand Cudappa, Andhra Pradesh- 5161 Bank of India, Guntur Branch, Door No.5-25-521, Main Rd, AGN9001 KOTHAPET GUNTUR 522 001 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta, P.B.No.66, Guntur (P), Dist.Guntur, AP - 522001. 8 Bank of India Branch,DOOR NO. 9-8-64,Sri Ram Nivas, AGW8001 GAJUWAKA BRANCH 530 026 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 9 Gajuwaka, Anakapalle Main Road-530026 GAJUWAKA BRANCH Bank of India Branch,DOOR NO. 9-8-64,Sri Ram Nivas, AGW9002 530 026 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH -

Ph.D. Synopsis Submitted to for the Award of Degree of Doctor Of

TO DEVELOP FLOOD FORECASTING APPROACH OF AHMEDABAD CITY, GUJARAT, INDIA Ph.D. Synopsis Submitted to GUJARAT TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY Ahmadabad, Gujarat July-2019 For the Award of Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Civil Engineering By UJAS DEVEN PANDYA Enrollment No: 149997106023 Under the Supervision of Dr. Dhruvesh P. Patel Assistant Professor, Civil Engineering Department School of Technology, PDPU Gandhinagar, Gujarat, India 1 Contents 1. Abstract……………………………………………………………….. 3 2. Brief description on the state of the art of the research topic………… 4 3. Definition of the problem …………………………………………….. 5 4. Objectives …………………..………………………………………… 6 5. Future Scope ………………….……………………………………… 7 6. Original contribution by the thesis…………………………….……… 7 7. Methodology of Research and Results………………………………... 7 8. Achievements with respect to objectives……………………………... 16 9. Conclusion…………………………………………………………….. 16 10. List of Paper publications………………………………………..….. 17 11. References…………………………………………………………… 18 2 1. Abstract: Flood is disastrous for developing countries, its assessment are important for flood risk management. Ahmedabad is largest city and former capital of Gujarat and included under the 100 Smart city project of India is situated 151.6 km downstream for Dharoi dam. The city has experienced floods in the year 1973, 1983, 1988, 1991, 1993, 1998, 2003, 2004, 2005 and 2006. Going by statistics the city has experienced flood in almost consecutive three to four years. In addition, AMC has developed the Sabarmati River Front along the banks across the city which narrows the river section. Whether any study about risk of flood vulnerability has been done prior to the implementation of the project is not clear. How the river will react during flood situation is a matter of speculation for general public. -

Life Membership 2011-18 Dec Telephone

LIFE MEMBERSHIP 2011-18 DEC TELEPHONE . Sl.No Name Designation ADDRESS NO SABZAZRE_NASEEBA-17,Muslim 1 A A MUNSHI HD Pharmasist soc. Navrangpura, AHMEDABAD 9979148439 380009. Gineshwar part - I Nr Kanti part 2 A B PANT EE(D) society,Ghatlodia Ahmedabad- 27604204 380061 B-32, Orchid park nr Shailby Hospital 3 A C Bajaj Mgr(Logistic) 9904981023 opp. Karnavati c;lub Satelite , A-22,Park Avenue New cg 4 A C Barua Dy.SE(P) 9427336696 roadChandkheda Ahmedabad-380005 22,Somvil Bunglows,Bhaikaka Nagar 5 A C Saini SE(P) Thaltej Ahmedabad-55 B-302.Chinubhai Tower Satelite 6 A D PATEL SE(P) 9428563893 Memnagar AHMEDABAD-52. 27,Konark Society Sabarmati 7 A D VAID DySE(E) 9898218428 Ahmedabad -380019 A-9 AL-Ashurfi Society,B/H Haider 8 A G SHAIKH AEE(P) Nagar, JUHAPAURA, Sarkhej Road 9428330591 AHMEDABAD 380055 B-27, Shardakrupa Society, B/H 9 A H Naik Dy. SE(P) Janatanagar Chandkheda, 27516085 GANDHINAGAR-382424. 66/7 Madini Chamber ,Mahakali 10 A I Shaikh AE(M) Temple Dudeshwar Shahibaug 9824591030 Ahmedabad 8 Sindhu Mahal soc. Ashram road Old 11 A J Sharma DM(HR) 9428008152 Vadaj Ahmedabad 380013. D-303 Aditya residency Motera 12 A K Dhawan GM(Res) 9428332121 Ahmedabad 380005. H-6,Karnavati Soc.GHB Chandkheda 13 A K GAHLAUT GM(P) 23296926 Ahmedabad-382424 Flat no 1001 Sangath Diomond 14 A K Gupta Exe.Director Tower nr PVR cinema Motera 9712922825 Ahmedabad 380005. 2nd floor Rituraj Apartment op Rupal 15 A K Gupta DGM(MM) flats nr Xavier Loyla school 9426612638 Ahmedabad B-77,RJESHWARI 09428330135- 16 A K MEHTA EE(M) SOCIETY,PO,TRAGAD,IOC ROAD 27508082 CHANDKHEDA AHMEDABAD-382470. -

A Study of Physico Chemical and Biological Characteristics of Sabarmati River Water in Ahmedabad City, Gujarat, India

Jr. of Industrial Pollution Control 34(1)(2018) pp 1877-1881 www.icontrolpollution.com Research Article A STUDY OF PHYSICO CHEMICAL AND BIOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF SABARMATI RIVER WATER IN AHMEDABAD CITY, GUJARAT, INDIA IKRAM QURESHI1*, DEVANG GANDHI1, SAMARTH ZARAD2 AND HARSHAL GANDHI2 1Department of Biosciences, Shri Jagdishprasad Jhabarmal Tibrewala University, Vidyanagari, Jhunjhunu, Rajasthan, India. 2Pollucon Laboratories Pvt. Ltd, Surat, Gujarat, India (Received 09 September, 2017; accepted 23 April, 2018) Key words: BOD, COD, DO, Sabarmati river, pH. ABSTRACT Sabarmati River water sample was analyzed for the Chemical and Biological parameters such as pH, BOD, DO, COD, Phosphate, Conductivity and Total Coliform Organisms. River water samples were seasonally collected from the location of Dr. Ambedkar bridge, Sardar bridge, Swami Vivekanand bridge, Gandhi bridge and Subhash bridge. Evolution of Chemical and Microbiological Test results concluds that Sabarmati river water does not classified in Class-A,B or C Category, hence water treatment and disinfection process of river water was required before its use for drinking purpose. INTRODUCTION analyzed as per IS 10500(2012) specifications. Water quality was evaluated as per specifications given in Sabarmati River Basin has a length about 300 km Indian Standard guideline IS 10500 (2012) and APHA and its covered the Rajasthan and Gujarat state. (Table 2). Sabarmati Basin covers total catchment area of 21674 km2 out of it 18550 km2 area covers in Gujarat state. Sampling Time: Water sampling was carried out Current Research paper focused on Sabarmati river in the second week of March 2016, July 2016 and water quality in Ahmedabad city. Total 15 river December 2016.