Trinidad & Tobago

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trade, War and Empire: British Merchants in Cuba, 1762-17961

Nikolaus Böttcher Trade, War and Empire: British Merchants in Cuba, 1762-17961 In the late afternoon of 4 March 1762 the British war fleet left the port of Spithead near Portsmouth with the order to attack and conquer “the Havanah”, Spain’s main port in the Caribbean. The decision for the conquest was taken after the new Spanish King, Charles III, had signed the Bourbon family pact with France in the summer of 1761. George III declared war on Spain on 2 January of the following year. The initiative for the campaign against Havana had been promoted by the British Prime Minister William Pitt, the idea, however, was not new. During the “long eighteenth century” from the Glorious Revolution to the end of the Napoleonic era Great Britain was in war during 87 out of 127 years. Europe’s history stood under the sign of Britain’s aggres sion and determined struggle for hegemony. The main enemy was France, but Spain became her major ally, after the Bourbons had obtained the Spanish Crown in the War of the Spanish Succession. It was in this period, that America became an arena for the conflict between Spain, France and England for the political leadership in Europe and economic predominance in the colonial markets. In this conflict, Cuba played a decisive role due to its geographic location and commercial significance. To the Spaniards, the island was the “key of the Indies”, which served as the entry to their mainland colonies with their rich resources of precious metals and as the meeting-point for the Spanish homeward-bound fleet. -

City of Port-Of-Spain Mass Egress Plan Executive Summary

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction Port-of-Spain (POS), the Capital City of Trinidad and Tobago is located in the county of St. George. It has a residential population of 49,031 and a population density of 4,086. Moreover, it has an average transient population on any given day of 350,000 persons. The Port of Spain Corporation (POSC) is vulnerable to a number of natural, man-made and technological hazards. The list of natural hazards includes, but not limited to, floods, earthquakes, hurricanes and landslides. Chiefly and most frequent among the natural hazards is flooding. When this event occurs, the result is excessive street flooding that inhibits the movement of individuals in and out of the City for approximately two-three hours, until flood waters subside. The intensity of the event is magnified by concurrent high tide. The purpose of the City of Port-of-Spain Mass Egress Plan is to address the safe and strategic movement of the mass number of people from places of danger in POS to areas deemed safe. This plan therefore endeavours to facilitate planned and unplanned egress of persons when severe flooding occurs in the City. Levels of Egress Fundamentally, the City of Port-of-Spain Mass Egress Plan establishes a three-tiered egress process: . Level 1 Egress is done using the regular operating mode of the resources of local government and non-government authorities. Level 2 Egress of the City overwhelms the capacity of the regular operating mode of the resources of local entities. At this level, the Disaster Management Unit (DMU) of the POSC will take control of the egress process through its Emergency Operations Centre (EOC). -

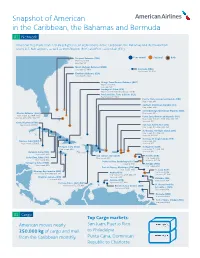

Snapshot of American in the Caribbean, the Bahamas and Bermuda 01 Network

Snapshot of American in the Caribbean, the Bahamas and Bermuda 01 Network American flies more than 170 daily flights to 38 destinations in the Caribbean, the Bahamas and Bermuda from seven U.S. hub airports, as well as from Boston (BOS) and Fort Lauderdale (FLL). Freeport, Bahamas (FPO) Year-round Seasonal Both Year-round: MIA Seasonal: CLT Marsh Harbour, Bahamas (MHH) Seasonal: CLT, MIA Bermuda (BDA) Year-round: JFK, PHL Eleuthera, Bahamas (ELH) Seasonal: CLT, MIA George Town/Exuma, Bahamas (GGT) Year-round: MIA Seasonal: CLT Santiago de Cuba (SCU) Year-round: MIA (Coming May 3, 2019) Providenciales, Turks & Caicos (PLS) Year-round: CLT, MIA Puerto Plata, Dominican Republic (POP) Year-round: MIA Santiago, Dominican Republic (STI) Year-round: MIA Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic (SDQ) Nassau, Bahamas (NAS) Year-round: MIA Year-round: CLT, MIA, ORD Punta Cana, Dominican Republic (PUJ) Seasonal: DCA, DFW, LGA, PHL Year-round: BOS, CLT, DFW, MIA, ORD, PHL Seasonal: JFK Grand Cayman (GCM) Year-round: CLT, MIA San Juan, Puerto Rico (SJU) Year-round: CLT, MIA, ORD, PHL St. Thomas, US Virgin Islands (STT) Year-round: CLT, MIA, SJU Seasonal: JFK, PHL St. Croix, US Virgin Islands (STX) Havana, Cuba (HAV) Year-round: MIA Year-round: CLT, MIA Seasonal: CLT Holguin, Cuba (HOG) St. Maarten (SXM) Year-round: MIA Year-round: CLT, MIA, PHL Varadero, Cuba (VRA) Seasonal: JFK Year-round: MIA Cap-Haïtien, Haiti (CAP) St. Kitts (SKB) Santa Clara, Cuba (SNU) Year-round: MIA Year-round: MIA Year-round: MIA Seasonal: CLT, JFK Pointe-a-Pitre, Guadeloupe (PTP) Camagey, Cuba (CMW) Seasonal: MIA Antigua (ANU) Year-round: MIA Year-round: MIA Fort-de-France, Martinique (FDF) Year-round: MIA St. -

Trinidad and Tobago Parliamentary Elections

Report of the Commonwealth Observer Group TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS 7 September 2015 Map Trinidad and Tobago Parliamentary Elections 7 September 2015 Table of Contents LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL .................................................................................... iv CHAPTER 1 ............................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1 Terms of Reference ............................................................................................ 1 Activities .............................................................................................................. 2 CHAPTER 2 ............................................................................................................... 3 Political Background ............................................................................................... 3 Early History ........................................................................................................ 3 Transition to independence ................................................................................. 3 Post-Independence Elections.............................................................................. 4 Context for the 2015 Parliamentary Elections ..................................................... 5 CHAPTER 3 .............................................................................................................. -

Waterford City Council Regular Meeting – June 18, 2015 - 6:30 Pm

AGENDA WATERFORD CITY COUNCIL - REGULAR MEETING WATERFORD CITY HALL, CITY COUNCIL CHAMBERS 101 “E” STREET, WATERFORD, CA WATERFORD CITY COUNCIL REGULAR MEETING – JUNE 18, 2015 - 6:30 PM CALL TO ORDER: Mayor Van Winkle FLAG SALUTE: Mayor Van Winkle INVOCATION: Greg Pace ROLL CALL: Mayor: Michael Van Winkle Vice Mayor: Jose Aldaco Council Members: Ken Krause, Joshua Whitfield, John Gothan ADOPTION OF AGENDA: A member of the City Council motions to accept the items on the agenda for consideration as presented, or motions for any additions, including emergency items, or items pulled from consideration. CONFLICT OF INTEREST DECLARATION: Declaration by City Council members who may have a direct Conflict of Interest on any scheduled agenda item to be considered. ADOPTION OF CONSENT CALENDAR: All Matters listed under the Consent Calendar are considered routine by the Council and will be adopted by one action of the Council unless any Council Member desires to discuss any item or items separately. In that event, the Mayor will remove that item from the Consent Calendar and action will be considered separately. 1. CONSENT CALENDAR 1a: Waive Readings - All readings of Ordinances and Resolutions, except by title, are waived 1b: RESOLUTION 2015-45: Warrant Register 1c: Minutes of the Regular City Council Meeting held on June 4, 2015 1d: Amendment to Professional Services Contract for Engineering Services 1e: Approve Pay Schedules for Fiscal Years 11-12, 12-13, 13-14, 14-15 and 15-16 2. PRESENTATIONS 2a: Introduction: New Employee – Kyle Perry 2b: Howard Training Center Update – Executive Director Carla Strong 3. COMMUNICATIONS FROM THE AUDIENCE This is the portion of the meeting specifically set aside to invite public comments regarding any matters not appearing on the agenda and within the jurisdiction of the City Council or the Successor Agency. -

20030912, House Debates

1 Papers Laid Friday, September 12, 2003 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Friday, September 12, 2003 The House met at 1.30 p.m. PRAYERS [MR. SPEAKER in the Chair] Mr. Speaker: Hon. Members, I have received correspondence requesting leave of absence from the following members: Hon. Camille Robinson-Regis, (Arouca South); Mrs. Eudine Job-Davis, (Tobago East) and Mr. Nizam Baksh, (Naparima). The leave of absence which these Members seek is granted. PAPERS LAID 1. Report of the Auditor General of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago on the financial statements of the Sangre Grande Regional Corporation for the nine-month period ended September 30, 1998. [The Minister of Health (Hon. Colm Imbert)] To be referred to the Public Accounts Committee. 2. The National Insurance (Benefit) (Amendment) Regulations, 2003. [Hon. C. Imbert] FINANCE COMMITTEE REPORT (Presentation) The Prime Minister and Minister of Finance (Hon. Patrick Manning): Mr. Speaker, I wish to present the Third Report 2002/2003 Session of the Finance Committee of the House of Representatives of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago on the proposal for the supplementation of the 2003 appropriation. HOUSE COMMITTEE REPORT (Presentation) The Minister of Health (Hon. Colm Imbert): Mr. Speaker, I wish to present the report of the House Committee of the House of Representatives 2002/2003 Session. COMMITTEE OF PRIVILEGES REPORT (Presentation) The Minister of Culture and Tourism (Hon. Pennelope Beckles): Mr. Speaker, I beg to lay on the Table, the House of Representatives Second Report of the Committee of Privileges 2002/2003 Session. 2 Standing Orders Committee Report Friday, September 12, 2003 STANDING ORDERS COMMITTEE REPORT (Presentation) The Minister of Health (Hon. -

Religion and the Alter-Nationalist Politics of Diaspora in an Era of Postcolonial Multiculturalism

RELIGION AND THE ALTER-NATIONALIST POLITICS OF DIASPORA IN AN ERA OF POSTCOLONIAL MULTICULTURALISM (chapter six) “There can be no Mother India … no Mother Africa … no Mother England … no Mother China … and no Mother Syria or Mother Lebanon. A nation, like an individual, can have only one Mother. The only Mother we recognize is Mother Trinidad and Tobago, and Mother cannot discriminate between her children. All must be equal in her eyes. And no possible interference can be tolerated by any country outside in our family relations and domestic quarrels, no matter what it has contributed and when to the population that is today the people of Trinidad and Tobago.” - Dr. Eric Williams (1962), in his Conclusion to The History of the People of Trinidad and Tobago, published in conjunction with National Independence in 1962 “Many in the society, fearful of taking the logical step of seeking to create a culture out of the best of our ancestral cultures, have advocated rather that we forget that ancestral root and create something entirely new. But that is impossible since we all came here firmly rooted in the cultures from which we derive. And to simply say that there must be no Mother India or no Mother Africa is to show a sad lack of understanding of what cultural evolution is all about.” - Dr. Brinsley Samaroo (Express Newspaper, 18 October 1987), in the wake of victory of the National Alliance for Reconstruction in December 1986, after thirty years of governance by the People’s National Movement of Eric Williams Having documented and analyzed the maritime colonial transfer and “glocal” transculturation of subaltern African and Hindu spiritisms in the southern Caribbean (see Robertson 1995 on “glocalization”), this chapter now turns to the question of why each tradition has undergone an inverse political trajectory in the postcolonial era. -

John Simm ~ 47 Screen Credits and More

John Simm ~ 47 Screen Credits and more The eldest of three children, actor and musician John Ronald Simm was born on 10 July 1970 in Leeds, West Yorkshire and grew up in Nelson, Lancashire. He attended Edge End High School, Nelson followed by Blackpool Drama College at 16 and The Drama Centre, London at 19. He lives in North London with his wife, actress Kate Magowan and their children Ryan, born on 13 August 2001 and Molly, born on 9 February 2007. Simm won the Best Actor award at the Valencia Film Festival for his film debut in Boston Kickout (1995) and has been twice BAFTA nominated (to date) for Life On Mars (2006) and Exile (2011). He supports Man U, is "a Beatles nut" and owns seven guitars. John Simm quotes I think I can be closed in. I can close this outer shell, cut myself off and be quite cold. I can cut other people off if I need to. I don't think I'm angry, though. Maybe my wife would disagree. I love Manchester. I always have, ever since I was a kid, and I go back as much as I can. Manchester's my spiritual home. I've been in London for 22 years now but Manchester's the only other place ... in the country that I could live. You never undertake a project because you think other people will like it - because that way lies madness - but rather because you believe in it. Twitter has restored my faith in humanity. I thought I'd hate it, but while there are lots of knobheads, there are even more lovely people. -

Democracy in the Caribbean a Cause for Concern

DEMOCRACY IN THE CARIBBEAN A CAUSE FOR CONCERN Douglas Payne April 7, 1995 Policy Papers on the Americas Democracy in the Caribbean A Cause for Concern Douglas W. Payne Policy Papers on the Americas Volume VI Study 3 April 7, 1995 CSIS Americas Program The Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), founded in 1962, is an independent, tax-exempt, public policy research institution based in Washington, DC. The mission of CSIS is to advance the understanding of emerging world issues in the areas of international economics, politics, security, and business. It does so by providing a strategic perspective to decision makers that is integrative in nature, international in scope, anticipatory in timing, and bipartisan in approach. The Center's commitment is to serve the common interests and values of the United States and other countries around the world that support representative government and the rule of law. * * * CSIS, as a public policy research institution, does not take specific policy positions. Accordingly, all views, positions, and conclusions expressed in this report should be understood to be solely those of the authors. © 1995 by the Center for Strategic and International Studies. This study was prepared under the aegis of the CSIS Policy Papers on the Americas series. Comments are welcome and should be directed to: Joyce Hoebing CSIS Americas Program 1800 K Street, NW Washington, DC 20006 Phone: (202) 775-3180 Fax: (202) 775-3199 Contents Preface ..................................................................................................................................................... -

Hsse & Leadership

LINKAGE SPECIAL EDITION 3/2018 AMCHAM T&T STALWART NICHOLAS GALT: THE HANDOVER LEADING THROUGH CHANGE HSSE & LEADERSHIP Building A Safety Culture IN THIS ISSUE: Cyber Incident Response Plan Our Economic Tipping Points The Not So Secret Secret of Great Leadership AMCHAM T&T AMCHAM ON THE INSIDE AS "THE PATHWAY TO THE AMERICAS", SOME OF AMCHAM T&T’S SERVICES ARE LISTED BELOW: Did you know? One-on-One Appointments AMCHAM T&T Organsing Your Event Our strong mix of formidable local and Through our local and international (Event must be trade or business-related) international member companies, strong connections as well as the international AMCHAM T&T can arrange the logistics of networking links, close association with the AMCHAM network, AMCHAM T&T can arrange your event, all arrangements including sending U.S. Embassy and alliances with the Association one-on-one appointments for companies out invitations via email or otherwise, and of American Chambers of Commerce in who are seeking to expand their business in special invitation to ministers / diplomatic Latin America and The Caribbean (AACCLA) Trinidad and Tobago and the Americas. corps, following up for responses, coordination all ensure rapid access to what you need of logistics at venue before and after function. to compete effectively both in local and overseas markets. We can therefore secure AMCHAM T&T Executive Info Session for members strategic information on doing Launching a new product or service? AMCHAM Join an AMCHAM T&T Committee! business in a particular country as well as T&T’s InfoSessions are an excellent way of • Chamber Experience and Imaging (CEI) set up introductions to the right business niche marketing to the decision makers of Committee organisations or companies in the U.S. -

A CASE STUDY of the INDEPENDENT in TRINIDAD by CASSANDRA

TRYING TO GO IT ALONE AND FAILING IN AN AUTHORITARIAN DEVELOPING STATE: A CASE STUDY OF THE INDEPENDENT IN TRINIDAD By CASSANDRA D. CRUICKSHANK A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN MASS COMMUNICATION UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2005 Copyright 2005 by Cassandra D. Cruickshank ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to gratefully acknowledge the enthusiastic supervision of Dr. Michael Leslie during this work. It was a pleasure and an education to work with someone as knowledgeable about international media as he is. I would also like to thank Dr. Howard Sid Pactor, Dr. Debbie Treise, Dr. Kim Walsh-Childers, Dr. Julian Williams and Dr. Jon Roosenraad for their guidance and participation as committee members. I am forever indebted to my parents, Clive Cruickshank and Veda Joseph- Cruickshank, for their understanding, endless patience and encouragement when it was most required. Finally, I am grateful to my best friend Terry Wilson. Sometimes I thought he wanted this degree more than I did, but I am thankful all the same that he was there to help me through the bad times. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................................................................................................. iii LIST OF TABLES............................................................................................................. vi ABSTRACT..................................................................................................................... -

1 the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR PEGGY BLACKFORD Interviewe

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR PEGGY BLACKFORD Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial Interview Date: November 28, 2016 Copyright 2017 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Birth/Education/Employment with IRS/Life in NYC Entered FS - 1972 Office of the Inspector General, Washington, DC 1972-1974 Nairobi, Kenya 1974-1976 Budget & Fiscal officer Office of Transportation, Washington, DC 1976-1978 GSO Sao Paulo, Brazil 1978 - 1981 Portuguese Language Training Administrative officer HR, Washington, DC 1981 -1983 Career Management officer Office of Southern African Affairs, Washington, DC 1983-1985 Political officer Harare Zimbabwe 1985-1987 Administrative officer Office of Political Military Affairs, Washington, DC 1987-1989 Executive Director Paris, France 1989- 1992 Personnel officer Bamako, Mali 1992- 1995 Deputy Chief of Mission 1 Bissau, Guinea-Bissau 1995-1998 Chief of mission Diplomat in Residence 1998-2000 City University of New York (CUNY) Short term assignments for State as retired annuitant 2000-2017 lots of travel and theater INTERVIEW Q: Today is the 28th of November, 2016 with Peggy Blackford. I’m doing it on behalf of the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training and I’m Charles Stuart Kennedy. You go by, I assume, by Peggy. BLACKFORD: I do; that is my name. Mother wanted to name me for my Aunt Margaret but she didn’t like the name Margaret and opted instead for Peggy which is a common nickname for Margaret. Q: Let’s start at the beginning. When and where were you born? BLACKFORD: I was born in Trenton, New Jersey, in 1942.