International Review for the History of Religions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lives of the Saints

Itl 1 i ill 11 11 i 11 i I 'M^iii' I III! II lr|i^ P !| ilP i'l ill ,;''ljjJ!j|i|i !iF^"'""'""'!!!|| i! illlll!lii!liiy^ iiiiiiiiiiHi '^'''liiiiiiiiilii ;ili! liliiillliili ii- :^ I mmm(i. MwMwk: llliil! ""'''"'"'''^'iiiiHiiiiiliiiiiiiiiiiiii !lj!il!|iilil!i|!i!ll]!; 111 !|!|i!l';;ii! ii!iiiiiiiiiiilllj|||i|jljjjijl I ili!i||liliii!i!il;.ii: i'll III ''''''llllllllilll III "'""llllllll!!lll!lllii!i I i i ,,„, ill 111 ! !!ii! : III iiii CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY l,wj Cornell Unrversity Library BR 1710.B25 1898 V.5 Lives ot the saints. Ili'lll I 3' 1924 026 082 572 Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924026082572 THE ilibes? of tlje t)atnt0 REV. S. BARING-GOULD SIXTEEN VOLUMES VOLUME THE FIFTH THE ILities of tlje g)amt6 BY THE REV. S. BARING-GOULD, M.A. New Edition in i6 Volumes Revised with Introduction and Additional Lives of English Martyrs, Cornish and Welsh Saints, and a full Index to the Entire Work ILLUSTRATED BY OVER 400 ENGRAVINGS VOLUME THE FIFTH LONDON JOHN C. NFMMO &-• NEW YORK . LONGMANS, GREEN. CO. MDCCCXCVIll / , >1< ^-Hi-^^'^ -^ / :S'^6 <d -^ ^' Printed by Ballantyne, Hanson &> CO. At the Ballantyne Press *- -»5< im CONTENTS PAGE Bernardine . 309 SS. Achilles and comp. 158 Boniface of Tarsus . 191 B. Alcuin 263 Boniface IV., Pope . 345 S. Aldhelm .... 346 Brendan of Clonfert 217 „ Alexander I., Pope . -

Newsletter the Personal Ordinariate of Our Lady of the Southern Cross Vol 1 No 2 2 April 2020 Passiontide

Newsletter The Personal Ordinariate of Our Lady of the Southern Cross Vol 1 No 2 2 April 2020 Passiontide The Ordinary’s Message We are not yet two weeks into the effective shut- down of group gatherings as a result of the current COVID-19 pandemic. In some ways it seems even longer than just that; however, we should be prepared for a much longer “new normal” with perhaps even stricter levels of isolation and/or Inside This Issue confinement that may persist for months. Page 2 But even as some might be beginning to experience feelings of cabin From the Philippines fever, have we noticed a few blessings? There is much less traffic Page 4 and the noise associated with it; in particular, far fewer airline flights, “Signs of Hope” a reprint from so many of which fly directly over us here in Homebush as they NCR (EWTN) arrive or leave the Sydney airport. And yet, the sound of silence, Page 7 much as it can be helpful to times of prayer, contemplation and Let’s get our patrons correct meditation, can also border on eerie. We live adjacent to a small, but normally well-used park, at the end of which is a day-care facility. I Page 8 miss the hum and noise of the cheerful laughter and yes, shouting, of Prayer for the Suffering children at play. Happily, while humanity is on a pandemically imposed “hold” the natural world continues as ever. The novelty for my wife and I, of the varied sounds of the sub-tropical birds, so much louder than the temperate zone birds of Canada, tell us that, while we humans effectively are holding our breath, the buzz of life otherwise continues. -

ICMA News...And More Summer 2020, No

ICMA NEWS...AND MORE Summer 2020, no. 2 Melanie Hanan, Editor Contents: FROM THE PRESIDENT, NINA ROWE ICMA News 1 Dear ICMA Members, From the President, Nina Rowe 1 I write to you at a moment of great challenge, but also promise. When I composed my President’s Statement of Solidarity letter for the spring issue of ICMA News, colleges and universities had only recently responded and Action 3 to the COVID-19 pandemic by moving teaching online and museums were just beginning to Member News 5 close their doors and reconsider exhibition and event schedules. Now, at the height of sum- Awards mer 2020, many among us are preoccupied with the care of loved ones, engaged with activist Books Appointments responses to social inequalities, and disoriented by uncertainties in our professional lives. At the Events ICMA we have taken measures to try to help our members weather this period and we have In the Media reason for optimism that we will come out stronger as an organization and community. Commemorations: 10 Walter Cahn, 1933 – 2020 It is good to be able to announce a development that will help us stay connected during a Paul Crossley, 1945-2019 time when we cannot gather in person. We applied for and received a grant from the National Robert Suckale, 1943-2020 Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) as part of the CARES government relief program to In Brief 16 fund a part-time, six-month hire—a Coordinator for Digital Engagement. By the moment that Special Features 20 this newsletter reaches you, we expect to have announced the position, reviewed applications, Reflections:Thoughts and perhaps even extended an offer for this important job. -

Edinburgh Research Explorer

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Edinburgh Research Explorer Edinburgh Research Explorer Civic piety and patriotism Citation for published version: Bowd, S 2016, 'Civic piety and patriotism: Patrician humanists and Jews in Venice and its empire ' Renaissance quarterly, vol. 69, no. 4, pp. 1257-1295. DOI: 10.1086/690313 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1086/690313 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Renaissance quarterly Publisher Rights Statement: Accepted for publication by Renaissance Quarterly on Winter 2016. http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/toc/rq/current General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 05. Apr. 2019 1 Civic Piety and Patriotism: Patrician Humanists and Jews in Venice and its Empire Stephen Bowd University of Edinburgh Abstract: This article focuses on the contribution of anti-Jewish themes to political ideals and reality in the works of two leading Venetian patrician humanists – Ludovico Foscarini (1409-80) and Paolo Morosini (1406-ca.1482). -

The Tortures and Torments of the Christian Martyrs

The Tortures and Torments of the Christian Martyrs (A Modern Edition) De SS. Martyrum Cruciatibus by Reverend Father Antonio Gallonio, translated from the Latin by A.R. Allison, 1591 Revised and Edited into Contemporary English by Geoffrey K. Mondello, Boston Catholic Journal. Copyright © 2013 All rights reserved. "Father Gallonio's work was intended for the edification of the Faithful, and was issued with the full authority and approbation of the Church." A. R. Allison Note: This translation by the Boston Catholic Journal has been edited for abstruse and confusing archaisms, needless redundancies, and rendered into Modern (American) English. It is our goal to render this important, historical document into an easily readable format. However, we encourage the reader to consult the following important link: Acta Martyrum for a necessary perspective on the important distinction between authentic Acta Matyrum, scholarly hagiography, and edifying historical literature. This does not pretend to be a scholarly edition, replete with footnotes and historical references. Indeed, the original vexes us with its inconsistent references, and the absence of any methodical attribution to the works or authors cited. However, it must be remembered that the present work is not offered to us as a compendium, or even a 1 work of scholarship. That is not its intended purpose. It is, however, intended to accompany the Roman Martyrology which the Boston Catholic Journal brings to you each day, in the way of supplementing the often abbreviated account of the Catholic Martyrs with an historical perspective and a deeper understanding of the suffering they endured for the sake of Christ, His Holy Catholic Church, and the Faith of our fathers which, in our own times, sadly, recedes from memory for the sake of temporizing our own Catholic Faith to accommodate the world at the cost of Christ. -

St. Timothy Trenton MI Bulletin 1-18-15

EASTER SUNDAY THE RESURRECTION OF THE LORD APRIL 12, 2020 ALLELUIA WHY HAVE YOU THIS IS Abandoned THE DAY THELord HAS MADE; LET US rejoice AND BE GLAD. PSALM 118 Resurrection of the Lord, © shutterstock.com/Zvonimir Athletic St. Timothy’s Guide, Trenton Page 2 GOSPEL MEDITATION - ENCOURAGE DEEPER UNDERSTANDING OF SCRIPTURE Easter Sunday of the Resurrection of the Lord When we awoke this morning, we found ourselves blessed with another day. It is Easter Sunday. As that thought crossed our minds, did we find ourselves saying “so what” or “alleluia”? For many, today is truly a day of alleluia. For others, it is just another day of “so what.” Faith makes a huge difference. It not only makes a differ- ence in how we understand today and the significance of what we celebrate, it also makes a huge difference in terms of how we understand ourselves. Succeed, live well, be productive, find your niche, fol- low your dreams, make money, protect your social status, be politically correct, and keep your preferences to yourself are pretty good examples of the messages our secular life wants us to hear. In and of themselves, they don’t sound all that harmful. But when really examined, they are. The life of resurrection embodied in the Gospel tells us a much different story. Life keeps us busy. We are always connected, distracted, occupied, and working. For many of us, an agen- da awaits us before we even start our day, and unfinished stuff is brought with us when we retire at night. Make the best of life and “find your own road to happiness are messages we all too easily believe. -

John Patrick Publishing

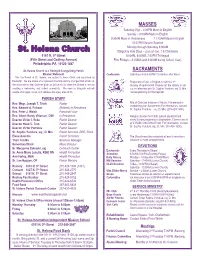

MASSES Saturday Vigil – 4:30PM Mass in English Sunday – 8:00AM Mass in English 9:30AM Mass in Vietnamese 11:15AM Mass in English 12:30PM Mass in Spanish Monday through Saturday 8:00AM Obligatory Holy Days – (except Jan. 1 & Christmas) 6161 N. 5th Street 8:00AM, 9:00AM, 7:00PM Tri-lingual (Fifth Street and Godfrey Avenue) First Fridays – 8:00AM (and 9:00AM during School Year) Philadelphia, PA 19120-1497 St. Helena Church is a Tithing & Evangelizing Parish SACRAMENTS Mission Statement Confession Saturdays 4:00-4:30PM 15 minutes after Mass We, the Parish of St. Helena, are rooted in Jesus Christ and nourished by Eucharist. We are aware of our present diversity and the changes that enrich us. Preparation Class in English is held the 1st We strive with all that God has given us to live and to share the Gospel of love by Sunday of each month. Please call the rectory to set creating a welcoming and united community. We seek to integrate actively up an interview with Sr. Sophie Yondura, ssj. D. Min. people of all ages, races, and cultures into every area of life. before planning for the baptism. PARISH STAFF Rev. Msgr. Joseph T. Trinh Pastor Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults. If interested in completing your Sacraments For information, contact Rev. Edward A. Pelczar (Retired) In Residence Sr. Sophie Yondura, ssj., D. Min. (215-424-1300). Rev. Peter J. Welsh Parochial Vicar Rev. Albert Gardy Villarson, OMI In Residence Religion classes for Public School students held Deacon Victor I. Seda Parish Deacon every Sunday beginning in September. -

St. Mary's Parish

St. Mary’s Parish Our Mission: Mass Schedule: “To know Christ and to make Him known.” Confession: Saturdays from Noon – 12:45 PM in the Monday through Saturday 8 Church St., Holliston, MA 01746 church or anytime by 9:00 AM appointment. Website: www.stmarysholliston.com Saturday Vigils Email Address: [email protected] Anointing of the Sick: Any 5:00 PM Rectory Phone: (508) 429 - 4427 or (508) 879 - 2322 time by appointment. Please 7:30 PM Religious Education Phone: (508) 429 - 6076 call as soon as you are aware Sunday Fax: (508) 429 - 3324 of a serious illness or 7:30 AM upcoming surgery. Dear Visitors: Welcome! We are delighted 9:30 AM Family Mass that you chose to worship with us this day. Baptism: The 2nd & 4th (C.L.O.W. Sept. – May) Please introduce yourself to the priest, and if Sunday of each month. To 11:30 AM Sung Mass you are interested in becoming a member of the register for Baptism Holy Days: Announced parish then please call the rectory to register. Preparation call 429-4427. Please also be aware that for generations it has Marriage: Please call at Adoration Schedule: been the custom at St. Mary’s to kneel together least 6 months in advance of First Fridays from for a silent Hail Mary at the end of Mass. your desired wedding date. 9:30-10:30 AM Please join in! Saint Mary’s Parish 8 Church St. ~ Holliston, MA ~ 01746 ~ (508) 429-4427 April 5, 2020 Palm Sunday Dear Members of the St. -

Roman Martyrology by Month

www.boston-catholic-journal.com Roman Martyrology by Month 1916 Edition January February March April May June July August September October November December The following is the complete text of the Roman Martyrology circa 1900 A.D. Many more Saints and Martyrs have since been entered into this calendar commemorating the heroic faith, the holy deeds, the exemplary lives, and in many cases the glorious deaths of these Milites Christi, or Soldiers of Christ, who gave 1 every fiber of their being to God for His glory, for the sanctification of His Holy Catholic Church, for the conversion of sinners both at home and in partibus infidelium 1, for the salvation of souls, and for the proclamation of the Gospel of Jesus Christ, even as He had last commanded His holy Apostles: “Euntes ergo docete omnes gentes: baptizantes eos in nomine Patris, et Filii, et Spiritus Sancti. Docentes eos servare omnia quæcumque mandavi vobis.” “Going therefore, teach all nations: baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost. Teaching them to observe all things whatsoever I have commanded you.” (St. Matthew 28.19-20) While the Martyrology presented is complete, it nevertheless does not present us with great detail concerning the lives of those whose names are forever indited within it, still less the complete circumstances surrounding and leading up to their martyrdom. For greater detail of their lives, the sources now available on the Internet are extensive and we encourage you to explore them.2 As it stands, the Martyrology is eminently suited to a brief daily reflection that will inspire us to greater fervor, even to imitate these conspicuously holy men and women in whatever measure our own state in life affords us through the grace and providence of Almighty God. -

5.. Gardens for the Soul

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) The Artful Hermit. Cardinal Odoardo Farnese's religious patronage and the spiritual maening of landsacpe around 1600 Witte, A.A. Publication date 2004 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Witte, A. A. (2004). The Artful Hermit. Cardinal Odoardo Farnese's religious patronage and the spiritual maening of landsacpe around 1600. in eigen beheer. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:02 Oct 2021 5.. GARDENS FOR THE SOUL inn i615. when Lanfranco will have started his work on the decoration in the Camerino, Cardinal Robertoo Bcilarmino published a book caiied Scala di satire con la menie a Dio per mezo delie cosecose create, a 'Ladder to ascend with the mind to God by means of the created things' (fig.82). -

The Golden Legend, Vol. 7

The Golden Legend, vol. 7 Author(s): Voragine, Jacobus de (1230-1298) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Subjects: Christian Denominations Roman Catholic Church Biography and portraits Collective Saints and martyrs i Contents Title Page 1 The Life of S. Katherine 2 The life of S. Saturnine 18 Remark 20 The Life of S. James the Martyr 21 The Life of Bede 24 The Life of S. Dorothy 26 The Life of S. Brandon 29 The Life of S. Erkenwold 39 The Life of the Abbot Pastor 42 The Life of the Abbot John 45 The Life of the Abbot Moses 46 The Life of S. Arsenius 47 The Life of the Abbot Agathon 50 The Life of Barlaam the Hermit 52 The History of S. Pelagius the Pope, the Lombards, Muhammed, and Others 63 The Life of S. Simeon 80 The Life of S. Polycarp 84 The Passion of S. Quiriacus 86 The Life of S. Thomas Aquinas 89 The Life of S. Gaius 93 The Life of S. Arnold 95 The Life of S. Tuien 99 The Life of S. Fiacre 101 The Life of S. Justin 105 The Life of S. Demetrius 106 ii The Life of S. Rigobert 108 The Life of S. Landry 110 The Life of S. Mellonin 112 The Life of S. Ives 113 The Life of S. Morant 119 The Life of S. Louis, King of France 121 The Life of s. Louis of Marseilles 127 The Life of S. Aldegonde 129 The Life of S. Albine 131 The History of the Exposition of the Mass 133 The Second Part of the Mass 138 The Third Part of the Mass 147 The Fourth Part of the Mass 150 The Twelve Articles of Our Faith 154 Translator's Afterword 156 Appendix 157 The Life of S. -

Martyrology of the Sacred Order of Friars Preachers

THE MARTYROLOGY OF THE SACRED ORDER OF FRIARS PREACHERS THE MARTYROLOGY OF THE SACRED ORDER OF FRIARS PREACHERS Translated by Rev. W. R. Bonniwell, O.P. THE NEWMAN PRESS + WESTMINSTER, MARYLAND 1955 [1998] Nihil obstat: FRANCIS N. WENDELL , 0. P. FERDINAND N. GEORGES , 0. P. Censores Librorum Imprimatur: MOST REV . T. S. MCDERMOTT , 0. P. Vicar General of the Order of Preachers November 12, 1954 Copyright, (c) 1955, by the NEWMAN PRESS Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 55-8660 Printed in the United States of America [This electronic edition: 1998] TO OUR BELOVED FATHERS , BROTHERS , AND SISTERS OF THE ORDER OF FRIARS PREACHERS , WE FATHER TERENCE STEPHEN MCDERMOTT MASTER OF SACRED THEOLOGY AND THE HUMBLE VICAR GENERAL AND SERVANT OF THE ENTIRE ORDER OF FRIARS PREACHERS GREETINGS AND BLESSINGS : With the rapid growth of the liturgical movement especially in the last quarter of a century, there has been an increasing volume of requests from Dominican Sisters and Lay Tertiaries for an English translation of our Breviary and Martyrology. It is with pleasure, therefore, that I am able to announce the fulfillment of these desires. The Breviary, translated by Father Aquinas Byrnes, O.P., is now in the process of publication at Rome, while the translation of the Dominican Martyrology has just completed. The Martyrology is one of the six official books of the Church's liturgy, its use in the choral recitation of the Divine Office is obligatory. Because of the salutary effects derived from the reading of this sacred volume, various Pontiffs have urged its use by those who recite the Office privately.