Mathematics Standards Introduction Outline of Mathematics Strands And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Variables in Mathematics Education

Variables in Mathematics Education Susanna S. Epp DePaul University, Department of Mathematical Sciences, Chicago, IL 60614, USA http://www.springer.com/lncs Abstract. This paper suggests that consistently referring to variables as placeholders is an effective countermeasure for addressing a number of the difficulties students’ encounter in learning mathematics. The sug- gestion is supported by examples discussing ways in which variables are used to express unknown quantities, define functions and express other universal statements, and serve as generic elements in mathematical dis- course. In addition, making greater use of the term “dummy variable” and phrasing statements both with and without variables may help stu- dents avoid mistakes that result from misinterpreting the scope of a bound variable. Keywords: variable, bound variable, mathematics education, placeholder. 1 Introduction Variables are of critical importance in mathematics. For instance, Felix Klein wrote in 1908 that “one may well declare that real mathematics begins with operations with letters,”[3] and Alfred Tarski wrote in 1941 that “the invention of variables constitutes a turning point in the history of mathematics.”[5] In 1911, A. N. Whitehead expressly linked the concepts of variables and quantification to their expressions in informal English when he wrote: “The ideas of ‘any’ and ‘some’ are introduced to algebra by the use of letters. it was not till within the last few years that it has been realized how fundamental any and some are to the very nature of mathematics.”[6] There is a question, however, about how to describe the use of variables in mathematics instruction and even what word to use for them. -

An Introduction to Mathematical Modelling

An Introduction to Mathematical Modelling Glenn Marion, Bioinformatics and Statistics Scotland Given 2008 by Daniel Lawson and Glenn Marion 2008 Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Whatismathematicalmodelling?. .......... 1 1.2 Whatobjectivescanmodellingachieve? . ............ 1 1.3 Classificationsofmodels . ......... 1 1.4 Stagesofmodelling............................... ....... 2 2 Building models 4 2.1 Gettingstarted .................................. ...... 4 2.2 Systemsanalysis ................................. ...... 4 2.2.1 Makingassumptions ............................. .... 4 2.2.2 Flowdiagrams .................................. 6 2.3 Choosingmathematicalequations. ........... 7 2.3.1 Equationsfromtheliterature . ........ 7 2.3.2 Analogiesfromphysics. ...... 8 2.3.3 Dataexploration ............................... .... 8 2.4 Solvingequations................................ ....... 9 2.4.1 Analytically.................................. .... 9 2.4.2 Numerically................................... 10 3 Studying models 12 3.1 Dimensionlessform............................... ....... 12 3.2 Asymptoticbehaviour ............................. ....... 12 3.3 Sensitivityanalysis . ......... 14 3.4 Modellingmodeloutput . ....... 16 4 Testing models 18 4.1 Testingtheassumptions . ........ 18 4.2 Modelstructure.................................. ...... 18 i 4.3 Predictionofpreviouslyunuseddata . ............ 18 4.3.1 Reasonsforpredictionerrors . ........ 20 4.4 Estimatingmodelparameters . ......... 20 4.5 Comparingtwomodelsforthesamesystem . ......... -

![Example 10.8 Testing the Steady-State Approximation. ⊕ a B C C a B C P + → → + → D Dt K K K K K K [ ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6323/example-10-8-testing-the-steady-state-approximation-a-b-c-c-a-b-c-p-d-dt-k-k-k-k-k-k-156323.webp)

Example 10.8 Testing the Steady-State Approximation. ⊕ a B C C a B C P + → → + → D Dt K K K K K K [ ]

Example 10.8 Testing the steady-state approximation. Å The steady-state approximation contains an apparent contradiction: we set the time derivative of the concentration of some species (a reaction intermediate) equal to zero — implying that it is a constant — and then derive a formula showing how it changes with time. Actually, there is no contradiction since all that is required it that the rate of change of the "steady" species be small compared to the rate of reaction (as measured by the rate of disappearance of the reactant or appearance of the product). But exactly when (in a practical sense) is this approximation appropriate? It is often applied as a matter of convenience and justified ex post facto — that is, if the resulting rate law fits the data then the approximation is considered justified. But as this example demonstrates, such reasoning is dangerous and possible erroneous. We examine the mechanism A + B ¾¾1® C C ¾¾2® A + B (10.12) 3 C® P (Note that the second reaction is the reverse of the first, so we have a reversible second-order reaction followed by an irreversible first-order reaction.) The rate constants are k1 for the forward reaction of the first step, k2 for the reverse of the first step, and k3 for the second step. This mechanism is readily solved for with the steady-state approximation to give d[A] k1k3 = - ke[A][B] with ke = (10.13) dt k2 + k3 (TEXT Eq. (10.38)). With initial concentrations of A and B equal, hence [A] = [B] for all times, this equation integrates to 1 1 = + ket (10.14) [A] A0 where A0 is the initial concentration (equal to 1 in work to follow). -

Chapter 1 the Field of Reals and Beyond

Chapter 1 The Field of Reals and Beyond Our goal with this section is to develop (review) the basic structure that character- izes the set of real numbers. Much of the material in the ¿rst section is a review of properties that were studied in MAT108 however, there are a few slight differ- ences in the de¿nitions for some of the terms. Rather than prove that we can get from the presentation given by the author of our MAT127A textbook to the previous set of properties, with one exception, we will base our discussion and derivations on the new set. As a general rule the de¿nitions offered in this set of Compan- ion Notes will be stated in symbolic form this is done to reinforce the language of mathematics and to give the statements in a form that clari¿es how one might prove satisfaction or lack of satisfaction of the properties. YOUR GLOSSARIES ALWAYS SHOULD CONTAIN THE (IN SYMBOLIC FORM) DEFINITION AS GIVEN IN OUR NOTES because that is the form that will be required for suc- cessful completion of literacy quizzes and exams where such statements may be requested. 1.1 Fields Recall the following DEFINITIONS: The Cartesian product of two sets A and B, denoted by A B,is a b : a + A F b + B . 1 2 CHAPTER 1. THE FIELD OF REALS AND BEYOND A function h from A into B is a subset of A B such that (i) 1a [a + A " 2bb + B F a b + h] i.e., dom h A,and (ii) 1a1b1c [a b + h F a c + h " b c] i.e., h is single-valued. -

Real Numbers and Their Properties

Real Numbers and their Properties Types of Numbers + • Z Natural numbers - counting numbers - 1, 2, 3,... The textbook uses the notation N. • Z Integers - 0, ±1, ±2, ±3,... The textbook uses the notation J. • Q Rationals - quotients (ratios) of integers. • R Reals - may be visualized as correspond- ing to all points on a number line. The reals which are not rational are called ir- rational. + Z ⊂ Z ⊂ Q ⊂ R. R ⊂ C, the field of complex numbers, but in this course we will only consider real numbers. Properties of Real Numbers There are four binary operations which take a pair of real numbers and result in another real number: Addition (+), Subtraction (−), Multiplication (× or ·), Division (÷ or /). These operations satisfy a number of rules. In the following, we assume a, b, c ∈ R. (In other words, a, b and c are all real numbers.) • Closure: a + b ∈ R, a · b ∈ R. This means we can add and multiply real num- bers. We can also subtract real numbers and we can divide as long as the denominator is not 0. • Commutative Law: a + b = b + a, a · b = b · a. This means when we add or multiply real num- bers, the order doesn’t matter. • Associative Law: (a + b) + c = a + (b + c), (a · b) · c = a · (b · c). We can thus write a + b + c or a · b · c without having to worry that different people will get different results. • Distributive Law: a · (b + c) = a · b + a · c, (a + b) · c = a · c + b · c. The distributive law is the one law which in- volves both addition and multiplication. -

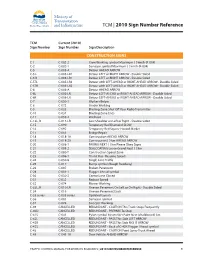

2010 Sign Number Reference for Traffic Control Manual

TCM | 2010 Sign Number Reference TCM Current (2010) Sign Number Sign Number Sign Description CONSTRUCTION SIGNS C-1 C-002-2 Crew Working symbol Maximum ( ) km/h (R-004) C-2 C-002-1 Surveyor symbol Maximum ( ) km/h (R-004) C-5 C-005-A Detour AHEAD ARROW C-5 L C-005-LR1 Detour LEFT or RIGHT ARROW - Double Sided C-5 R C-005-LR1 Detour LEFT or RIGHT ARROW - Double Sided C-5TL C-005-LR2 Detour with LEFT-AHEAD or RIGHT-AHEAD ARROW - Double Sided C-5TR C-005-LR2 Detour with LEFT-AHEAD or RIGHT-AHEAD ARROW - Double Sided C-6 C-006-A Detour AHEAD ARROW C-6L C-006-LR Detour LEFT-AHEAD or RIGHT-AHEAD ARROW - Double Sided C-6R C-006-LR Detour LEFT-AHEAD or RIGHT-AHEAD ARROW - Double Sided C-7 C-050-1 Workers Below C-8 C-072 Grader Working C-9 C-033 Blasting Zone Shut Off Your Radio Transmitter C-10 C-034 Blasting Zone Ends C-11 C-059-2 Washout C-13L, R C-013-LR Low Shoulder on Left or Right - Double Sided C-15 C-090 Temporary Red Diamond SLOW C-16 C-092 Temporary Red Square Hazard Marker C-17 C-051 Bridge Repair C-18 C-018-1A Construction AHEAD ARROW C-19 C-018-2A Construction ( ) km AHEAD ARROW C-20 C-008-1 PAVING NEXT ( ) km Please Obey Signs C-21 C-008-2 SEALCOATING Loose Gravel Next ( ) km C-22 C-080-T Construction Speed Zone C-23 C-086-1 Thank You - Resume Speed C-24 C-030-8 Single Lane Traffic C-25 C-017 Bump symbol (Rough Roadway) C-26 C-007 Broken Pavement C-28 C-001-1 Flagger Ahead symbol C-30 C-030-2 Centre Lane Closed C-31 C-032 Reduce Speed C-32 C-074 Mower Working C-33L, R C-010-LR Uneven Pavement On Left or On Right - Double Sided C-34 -

Advanced Discrete Mathematics Mm-504 &

1 ADVANCED DISCRETE MATHEMATICS M.A./M.Sc. Mathematics (Final) MM-504 & 505 (Option-P3) Directorate of Distance Education Maharshi Dayanand University ROHTAK – 124 001 2 Copyright © 2004, Maharshi Dayanand University, ROHTAK All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means; electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the written permission of the copyright holder. Maharshi Dayanand University ROHTAK – 124 001 Developed & Produced by EXCEL BOOKS PVT. LTD., A-45 Naraina, Phase 1, New Delhi-110 028 3 Contents UNIT 1: Logic, Semigroups & Monoids and Lattices 5 Part A: Logic Part B: Semigroups & Monoids Part C: Lattices UNIT 2: Boolean Algebra 84 UNIT 3: Graph Theory 119 UNIT 4: Computability Theory 202 UNIT 5: Languages and Grammars 231 4 M.A./M.Sc. Mathematics (Final) ADVANCED DISCRETE MATHEMATICS MM- 504 & 505 (P3) Max. Marks : 100 Time : 3 Hours Note: Question paper will consist of three sections. Section I consisting of one question with ten parts covering whole of the syllabus of 2 marks each shall be compulsory. From Section II, 10 questions to be set selecting two questions from each unit. The candidate will be required to attempt any seven questions each of five marks. Section III, five questions to be set, one from each unit. The candidate will be required to attempt any three questions each of fifteen marks. Unit I Formal Logic: Statement, Symbolic representation, totologies, quantifiers, pradicates and validity, propositional logic. Semigroups and Monoids: Definitions and examples of semigroups and monoids (including those pertaining to concentration operations). -

An Elementary Approach to Boolean Algebra

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Plan B Papers Student Theses & Publications 6-1-1961 An Elementary Approach to Boolean Algebra Ruth Queary Follow this and additional works at: https://thekeep.eiu.edu/plan_b Recommended Citation Queary, Ruth, "An Elementary Approach to Boolean Algebra" (1961). Plan B Papers. 142. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/plan_b/142 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Plan B Papers by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. r AN ELEr.:ENTARY APPRCACH TC BCCLF.AN ALGEBRA RUTH QUEAHY L _J AN ELE1~1ENTARY APPRCACH TC BC CLEAN ALGEBRA Submitted to the I<:athematics Department of EASTERN ILLINCIS UNIVERSITY as partial fulfillment for the degree of !•:ASTER CF SCIENCE IN EJUCATION. Date :---"'f~~-----/_,_ffo--..i.-/ _ RUTH QUEARY JUNE 1961 PURPOSE AND PLAN The purpose of this paper is to provide an elementary approach to Boolean algebra. It is designed to give an idea of what is meant by a Boclean algebra and to supply the necessary background material. The only prerequisite for this unit is one year of high school algebra and an open mind so that new concepts will be considered reason able even though they nay conflict with preconceived ideas. A mathematical science when put in final form consists of a set of undefined terms and unproved propositions called postulates, in terrrs of which all other concepts are defined, and from which all other propositions are proved. -

Differentiation Rules (Differential Calculus)

Differentiation Rules (Differential Calculus) 1. Notation The derivative of a function f with respect to one independent variable (usually x or t) is a function that will be denoted by D f . Note that f (x) and (D f )(x) are the values of these functions at x. 2. Alternate Notations for (D f )(x) d d f (x) d f 0 (1) For functions f in one variable, x, alternate notations are: Dx f (x), dx f (x), dx , dx (x), f (x), f (x). The “(x)” part might be dropped although technically this changes the meaning: f is the name of a function, dy 0 whereas f (x) is the value of it at x. If y = f (x), then Dxy, dx , y , etc. can be used. If the variable t represents time then Dt f can be written f˙. The differential, “d f ”, and the change in f ,“D f ”, are related to the derivative but have special meanings and are never used to indicate ordinary differentiation. dy 0 Historical note: Newton used y,˙ while Leibniz used dx . About a century later Lagrange introduced y and Arbogast introduced the operator notation D. 3. Domains The domain of D f is always a subset of the domain of f . The conventional domain of f , if f (x) is given by an algebraic expression, is all values of x for which the expression is defined and results in a real number. If f has the conventional domain, then D f usually, but not always, has conventional domain. Exceptions are noted below. -

Kind of Quantity’

NIST Technical Note 2034 Defning ‘kind of quantity’ David Flater This publication is available free of charge from: https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.TN.2034 NIST Technical Note 2034 Defning ‘kind of quantity’ David Flater Software and Systems Division Information Technology Laboratory This publication is available free of charge from: https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.TN.2034 February 2019 U.S. Department of Commerce Wilbur L. Ross, Jr., Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology Walter Copan, NIST Director and Undersecretary of Commerce for Standards and Technology Certain commercial entities, equipment, or materials may be identifed in this document in order to describe an experimental procedure or concept adequately. Such identifcation is not intended to imply recommendation or endorsement by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, nor is it intended to imply that the entities, materials, or equipment are necessarily the best available for the purpose. National Institute of Standards and Technology Technical Note 2034 Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Tech. Note 2034, 7 pages (February 2019) CODEN: NTNOEF This publication is available free of charge from: https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.TN.2034 NIST Technical Note 2034 1 Defning ‘kind of quantity’ David Flater 2019-02-06 This publication is available free of charge from: https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.TN.2034 Abstract The defnition of ‘kind of quantity’ given in the International Vocabulary of Metrology (VIM), 3rd edition, does not cover the historical meaning of the term as it is most commonly used in metrology. Most of its historical meaning has been merged into ‘quantity,’ which is polysemic across two layers of abstraction. -

On the Relation Between Hyperrings and Fuzzy Rings

ON THE RELATION BETWEEN HYPERRINGS AND FUZZY RINGS JEFFREY GIANSIRACUSA, JAIUNG JUN, AND OLIVER LORSCHEID ABSTRACT. We construct a full embedding of the category of hyperfields into Dress’s category of fuzzy rings and explicitly characterize the essential image — it fails to be essentially surjective in a very minor way. This embedding provides an identification of Baker’s theory of matroids over hyperfields with Dress’s theory of matroids over fuzzy rings (provided one restricts to those fuzzy rings in the essential image). The embedding functor extends from hyperfields to hyperrings, and we study this extension in detail. We also analyze the relation between hyperfields and Baker’s partial demifields. 1. Introduction The important and pervasive combinatorial notion of matroids has spawned a number of variants over the years. In [Dre86] and [DW91], Dress and Wenzel developed a unified framework for these variants by introducing a generalization of rings called fuzzy rings and defining matroids with coefficients in a fuzzy ring. Various flavors of matroids, including ordinary matroids, oriented matroids, and the valuated matroids introduced in [DW92], correspond to different choices of the coefficient fuzzy ring. Roughly speaking, a fuzzy ring is a set S with single-valued unital addition and multiplication operations that satisfy a list of conditions analogous to those of a ring, such as distributivity, but only up to a tolerance prescribed by a distinguished ideal-like subset S0. Beyond the work of Dress and Wenzel, fuzzy rings have not yet received significant attention in the literature. A somewhat different generalization of rings, known as hyperrings, has been around for many decades and has been studied very broadly in the literature. -

Glossary of Linear Algebra Terms

INNER PRODUCT SPACES AND THE GRAM-SCHMIDT PROCESS A. HAVENS 1. The Dot Product and Orthogonality 1.1. Review of the Dot Product. We first recall the notion of the dot product, which gives us a familiar example of an inner product structure on the real vector spaces Rn. This product is connected to the Euclidean geometry of Rn, via lengths and angles measured in Rn. Later, we will introduce inner product spaces in general, and use their structure to define general notions of length and angle on other vector spaces. Definition 1.1. The dot product of real n-vectors in the Euclidean vector space Rn is the scalar product · : Rn × Rn ! R given by the rule n n ! n X X X (u; v) = uiei; viei 7! uivi : i=1 i=1 i n Here BS := (e1;:::; en) is the standard basis of R . With respect to our conventions on basis and matrix multiplication, we may also express the dot product as the matrix-vector product 2 3 v1 6 7 t î ó 6 . 7 u v = u1 : : : un 6 . 7 : 4 5 vn It is a good exercise to verify the following proposition. Proposition 1.1. Let u; v; w 2 Rn be any real n-vectors, and s; t 2 R be any scalars. The Euclidean dot product (u; v) 7! u · v satisfies the following properties. (i:) The dot product is symmetric: u · v = v · u. (ii:) The dot product is bilinear: • (su) · v = s(u · v) = u · (sv), • (u + v) · w = u · w + v · w.