HSCTP-CD.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016-2017 Annual Report

2016-2017 ANNUAL REPORT 1 Honorable Kay Ivey Governor of Alabama State Capitol Montgomery, AL 36130 Dear Governor Ivey: I am pleased to submit the Department of Conservation and Natural Resources’ Annual Report for Fiscal Year 2016-17. The Department continues to find more efficient ways to communicate and con- duct business with our constituents. License purchases, special hunt registrations and park lodge and camping reservations are available through our websites, www.outdooralabama.com and www.alapark.com. In addition, we are communi- cating to more than half a million people through email newsletters and notices. Funds derived from the cap on sales tax discounts were restored to State Parks in FY 2017. These funds have provided much-needed relief in addressing the back- log of park maintenance projects. Park guests totaled just under 5 million this fiscal year. The federal management of red snapper and other reef fish continues to be a highly volatile issue within the fishing community. Our Marine Resources Division is working with federal agencies and Congress to provide more state oversight of this fishery and a longer season for anglers. Snapper Check, which continued for the fourth year, is an important part of this effort. The State Lands Division has administered the Coastal Impact Assistance Program (CIAP) on behalf of the State of Alabama since its beginning in 2005. During the life of this program, which closed this year, State Lands administered 49 grants for over $58 million funding various coastal project activities supporting Mobile and Baldwin counties. Participation in the state’s Game Check system for the recording and reporting of both deer and turkey harvests became mandatory during the 2016/2017 hunting seasons. -

2013 Where to Go Camping Guide

2013 Where To Go Camping Guide A Publicaon of the Coosa Lodge of the Greater Alabama Council 504501.",*/(5)$&/563: 8)&3&50(0$".1*/((6*%&4 XXXXIFSFUPHPTDPVUJOHPSH Where to go Camping Guide Table of Contents In Council Camps………………………………………….3 High Adventure Bases…………………………………..5 Alabama State Parks……………………………………8 Wildlife Refuge…………………………………………….19 Points of Interest………………………………….………20 Places to Hike………………………………………………21 Sites to See……………………………………………………24 Maps……………………………………………………………25 Order of the Arrow………………………………...…….27 2 Boy Scout Camps Council Camps Each Campsite is equipped with a flagpole, trashcan, faucet, and latrine (Except Eagle and Mountain Goat) with washbasin. On the side of the latrine is a bulletin board that the troop can use to post assignments, notices, and duty rosters. Camp Comer has two air- conditioned shower and restroom facilities for camp-wide use. Patrol sites are pre- established in each campsite. Most Campsites have some Adarondaks that sleep four and tents on platforms that sleep two. Some sites may be occupied by more than one troop. Troops are encouraged to construct gateways to their campsites. The Hawk Campsite is a HANDICAPPED ONLY site; if you do not have a scout or leader that is handicapped that site will not be available. There are four troop campsites; each campsite has a latrine, picnic table and fire ring. Water may be obtained at spigots near the pavilion. Garbage is disposed of at the Tannehill trash dumpster. Each unit is responsible for providing its trash bags and taking garbage to the trash dumpster. The campsites have a number and a name. Make reservations at a Greater Alabama Council Service Center; be sure to specify the campsite or sites desired. -

Where to Go Camping Guidebook

2010 Greater Alabama Council Where to Go Camp ing Guidebook Published by the COOSA LODGE WHERE TO GO CAMPING GUIDE Table of Contents In Council Camps 2 High Adventure Bases 4 Alabama State Parks 7 Georgia State Parks 15 Mississippi State Parks 18 Tennessee State Parks 26 Wildlife Refuge 40 Points of Interest 40 Wetlands 41 Places to Hike 42 Sites to See 43 Maps 44 Order of the Arrow 44 Future/ Wiki 46 Boy Scouts Camps Council Camps CAMPSITES Each Campsite is equipped with a flagpole, trashcan, faucet, and latrine (Except Eagle and Mountain Goat) with washbasin. On the side of the latrine is a bulletin board that the troop can use to post assignments, notices, and duty rosters. Camp Comer has two air-conditioned shower and restroom facilities for camp-wide use. Patrol sites are pre-established in each campsite. Most campsites have some Adarondaks that sleep four and tents on platforms that sleep two. Some sites may be occupied by more than one troop. Troops are encouraged to construct gateways to their campsites. The Hawk Campsite is a HANDICAPPED ONLY site, if you do not have a scout or leader that is handicapped that site will not be available. There are four troop / campsites; each campsite has a latrine, picnic table and fire ring. Water may be obtained at spigots near the pavilion. Garbage is disposed of at the Tannehill trash dumpster. Each unit is responsible for providing its trash bags and taking garbage to the trash dumpster. The campsites have a number and a name. Make reservations at a Greater Alabama Council Service Center; be sure to specify the campsite or sites desired. -

RV Sites in the United States Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile

RV sites in the United States This GPS POI file is available here: https://poidirectory.com/poifiles/united_states/accommodation/RV_MH-US.html Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile Camp Map 370 Lakeside Park Map 5 Star RV Map 566 Piney Creek Horse Camp Map 7 Oaks RV Park Map 8th and Bridge RV Map A AAA RV Map A and A Mesa Verde RV Map A H Hogue Map A H Stephens Historic Park Map A J Jolly County Park Map A Mountain Top RV Map A-Bar-A RV/CG Map A. W. Jack Morgan County Par Map A.W. Marion State Park Map Abbeville RV Park Map Abbott Map Abbott Creek (Abbott Butte) Map Abilene State Park Map Abita Springs RV Resort (Oce Map Abram Rutt City Park Map Acadia National Parks Map Acadiana Park Map Ace RV Park Map Ackerman Map Ackley Creek Co Park Map Ackley Lake State Park Map Acorn East Map Acorn Valley Map Acorn West Map Ada Lake Map Adam County Fairgrounds Map Adams City CG Map Adams County Regional Park Map Adams Fork Map Page 1 Location Map Adams Grove Map Adelaide Map Adirondack Gateway Campgroun Map Admiralty RV and Resort Map Adolph Thomae Jr. County Par Map Adrian City CG Map Aerie Crag Map Aeroplane Mesa Map Afton Canyon Map Afton Landing Map Agate Beach Map Agnew Meadows Map Agricenter RV Park Map Agua Caliente County Park Map Agua Piedra Map Aguirre Spring Map Ahart Map Ahtanum State Forest Map Aiken State Park Map Aikens Creek West Map Ainsworth State Park Map Airplane Flat Map Airport Flat Map Airport Lake Park Map Airport Park Map Aitkin Co Campground Map Ajax Country Livin' I-49 RV Map Ajo Arena Map Ajo Community Golf Course Map -

The Alabama Municipal Journal March/April 2020 Volume 77, Number 5

The Alabama Municipal JournalVolume 77, Number 5 March/April 2020 OPI OOPPIIOOIIID CR IOIDD CCRIISIIS RIISSIISS S G NGG IINNG KIIN ICKK FIICC FFFI FFF AF RAA TRR T T T N N AAN AA M M UUM UU HH H H CC CC OO OO MM MM MM M M U U U U N N N N I I C C I I C C A A A A T T T T I I O O I I O O N N N N H H H H EE EEAA A ALL LLT TT H H HHC CCA AAR R R RE E EE A HEALTHY LIFESTYLES AAC HEALTHYHEALTHY LIFESTYLESLIFESTYLES C CC C CEES ES SS SS SS S S S S E S E S N S N S E SS E N S E N HOMELLEESSSS HHOOMMEEL 2 Official Publication:ALABAMA LEAGUE OF MUNICIPALITIES Table of Contents The Alabama Municipal League Past Presidents Mayors George Roy, Alvin DuPont and Ted Jennings Remembered for their Leadership and Dedication .....................................4 Journal The President’s Report............................................5 Executive Committee Endorses Greg Cochran as Official Publication, Alabama League of Municipalities Next Executive Director; Revisions to Constitution March/April 2020 • Volume 77, Number 5 Barry Crabb Joins League Staff ............................6 OFFICERS Municipal Overview ................................................7 RONNIE MARKS, Mayor, Athens, President Reflections on 34 Years with the League LEIGH DOLLAR, Mayor, Guntersville, Vice President KEN SMITH, Montgomery, Executive Director CHAIRS OF THE LEAGUE’S STANDING COMMITTEES Quality of Life Factors: Committee on State and Federal Legislation Homelessness ................................................................9 ADAM BOURNE, Councilmember, Chickasaw, Chair -

REQUEST for PROPOSALS State Parks Reservations and Point Of

REQUEST FOR PROPOSALS Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources State Parks Division State Parks Reservations and Point of Sale System CAMPGROUNDS, CABINS, AND DAY USE FACILITIES – CRS419 OVERVIEW The State Parks Division (SPD) of the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (ADCNR) is interested in obtaining integrated technology solutions for park business needs. These solutions should include, at a minimum, a Campground Reservation System (“CRS”) capable of supporting online, in-person, and park level reservations for multiple locations statewide on a 24/7 basis; and a Point of Sale (POS) system capable of supporting over $23 million in financial transactions on an annual basis. Proposed solution should offer convenience to park visitors, staff, and management, and should offer integration capabilities for mobile devices and personal computer dashboard reporting and management. Offering increased access to our parks as well as gaining access to visitor information to support trend analysis, planning and marketing are important ADCNR priorities. Proposed solution must support these priorities while complying with the Americans with Disabilities Act for accessibility and inclusion. The initial Contract term will be three (3) years followed by two (2) additional option periods of one (1) year each. 1 ADCNR RFP# CRS419 – 4/30/2019 1 RFP Specifications and General Terms and Conditions 1.1 Compliance with Specifications This document outlines the specifications and qualifications which must be met in order -

County Attractions

ALABAMA TOURISM DEPARTMENT’S CARES ACT RECOVERY CAMPAIGN County Representative and Attractions List AUTAUGA COUNTY: Prattville Area Chamber of Commerce – Anne Sanford • Attractions o Robert Trent Jones Golf Trail at Capitol Hill o Continental Gin Company o Daniel Pratt Historic District BALDWIN COUNTY/ GULF SHORES: Gulf Shores & Orange Beach Tourism – Herb Malone Team Members: Gulf Shores & Orange Beach Tourism – Laura Beebe, Joanie Flynn Eastern Shore Chamber of Commerce – Casey Williams • Attractions o Alabama Gulf Coast Zoo o Coastal Arts Center of Orange Beach o Cotton Bayou - A Gulf State Park Beach Area o Gulf Place - Gulf Shores Main Public Beach o Historic Blakeley State Park o Fairhope Municipal Pier (pending approval by City Officials) o OWA o Gulf State Park BARBOUR COUNTY: Eufaula Barbour County Chamber – Ann Sparks • Attractions o James S. Clark Interpretive Center o Fendall Hall o Lakepoint State Park Resort o Yoholo Micco Rail Trail BIBB COUNTY: Bibb County Chamber – Valerie Cook Team Members: UA Center for Economic Development – Candace Johnson- Beers • Attractions o Brierfield Ironworks Historical State Park o Cahaba River National Wildlife Refuge o Coke Ovens Park BLOUNT COUNTY: Alabama Mountain Lakes Tourist Association/ North Alabama Tourism Tami Reist • Attractions o Palisades Park o Rickwood Caverns State Park BULLOCK COUNTY: Bullock County Tourism – Midge Putnam Team Members: Tourism Council of Bullock County Board Members • Attractions o Eddie Kendricks Mural o Hank Williams Mural o Field Trails Mural - updated in portal o Bird Dog Monument BUTLER COUNTY: Alabama Black Belt Adventures – Pam Swanner Team Members: Greenville Area Chamber – Tracy Salter • Attractions o Robert Trent Jones Golf Trail at Cambrian Ridge o Sherling Lake Park & Campground o Hank Williams Sr. -

Southeast Alabama Regional Planning and Development Commission

2017-2019 Southeast Alabama Regional Planning and Development Commission Region 7 Serving the counties of: Barbour, Coffee, Covington, Dale, Geneva, Henry & Houston Prepared by the Southeast Alabama Regional Planning and Development Commission In cooperation with the Alabama Association of Regional Councils (AARC) and the Alabama Department of Transportation (ALDOT) September 2017 Reproduction of this document, in whole or in part, is permitted as long as appropriate attribution is made. The preparation of this report was financed, in part, by the Alabama Department of Transportation (ALDOT). For information or copies, contact: Southeast Alabama Regional Planning and Development Commission 462 North Oates Street P.O. Box 1406 Dothan, AL 36302 Planning Area: Barbour, Coffee, Covington, Dale, Geneva, Henry and Houston counties, including the Southeast Wiregrass Area Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) and the Southeast Alabama Rural Planning Organization (RPO) Lead Agency: Southeast Alabama Regional Planning & Development Commission Contact Persons: Scott Farmer, Community Development Director [email protected] Darrell Rigsby, Transportation Director [email protected] Telephone: (334) 794-4093 ii Abstract: This document is the Human Services Coordinated Transportation Plan for the Southeast Alabama Region 2017-2019, which updates the product that the Southeast Alabama Regional Planning and Development Commission (SEARP&DC) most recently published in September 2015. The Human Services Coordinated Transportation Plan for the Southeast Alabama Region 2017-2019 is developed in accordance with the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act, as well as former transportation bills, including the Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users (SAFETEA–LU) and the Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century (MAP-21) federal transportation reauthorizations. -

Fiscal Year 2019 Annual Report

ALABAMA DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION AND NATURAL RESOURCES 2018-2019 ANNUAL REPORT 1 BRAD LACKEY 2 The Honorable Kay Ivey Governor of Alabama State Capitol Montgomery, AL 36130 Dear Governor Ivey: I am pleased to submit the Department of Conservation and Natural Resources’ Annual Report for the scal year ending September 30, 2019. The Department continues to nd new ways to serve the public while adhering to our mission of promoting the wise stewardship and enjoyment of Alabama’s natural resources for current and future generations. In 2019, Gulf State Park was named Attraction of the Year by the Alabama Tourism Department. This distinction was due in part to the grand opening of the park’s new lodge, the rst at the park since Hurricane Ivan destroyed the previous lodge in 2004. Gulf State Park’s Eagle Cottages were also included in National Geographic’s Unique Lodges of the World Program. The cottages are one of seven locations in the U.S. to be included in the program with only 55 lodges in the program worldwide. We can now offer world-class destinations within one of the most beautiful state parks along the Gulf Coast. The Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries Division’s Adult Mentored Hunting Program continued to be a successful tool for recruiting hunters, bringing in 88 new hunters to participate in 13 adult mentored hunting events. Programs like this build on our already-established youth hunting programs with a goal of creating more hunters who will purchase the licenses that provide so much of the Department’s revenue. The 2019 red snapper shing season was managed under an Exempted Fishing Permit issued by the National Marine Fisheries Service. -

Roundabout Publications PO Box 19235 Lenexa

Published by: Roundabout Publications P.O. Box 19235 Lenexa, KS 66285 800-455-2207 www.TravelBooksUSA.com RV Camping in State Parks, copyright © 2015 by David J. Davin. Printed and bound in the United States of America. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without the prior written permission of the author. Although efforts are made to ensure the accuracy of this publication, the author and Roundabout Publications shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to be caused, directly or indirectly by the information contained in this publication. Published by: Roundabout Publications P.O. Box 19235 Lenexa, KS 66285 Phone: 800-455-2207 Internet: www.TravelBooksUSA.com Library of Congress Control Number: 2014943154 ISBN-10: 1-885464-57-6 ISBN-13: 978-1-885464-57-6 Contents Introduction.......................................................................4 Montana............................................................................97 Alabama...............................................................................5 Nebraska.........................................................................100 Alaska...................................................................................8 Nevada............................................................................105 Arizona...............................................................................13 New.Hampshire...........................................................108 -

Game, Fish, Furbearers, and Other Wildlife

ALABAMA REGULATIONS 2017-2018 GAME, FISH, FURBEARERS, AND OTHER WILDLIFE REGULATIONS RELATING TO GAME, FISH, FURBEARERS AND OTHER WILDLIFE KAY IVEY Governor CHRISTOPHER M. BLANKENSHIP Commissioner EDWARD F. POOLOS Deputy Commissioner CHUCK SYKES Director FRED R. HARDERS Assistant Director The Department of Conservation and Natural Resources does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, age, gender, national origin or disability in its hiring or employment practices nor in admission to, access to, or operations of its programs, services or activities. This publication is available in alternative formats upon request. O.E.O. U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. 20204 TABLE OF CONTENTS Division of Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries Personnel: Administrative Office .......................................... 1 Aquatic Education ................................................ 8 Carbon Hill Fish Hatchery ................................... 7 Eastaboga Fish Hatchery ...................................... 7 Federal Game Agents ............................................ 5 Fisheries Section ................................................... 6 Fisheries Development ......................................... 8 Hunter Education ................................................ 11 Law Enforcement Section ..................................... 2 Marion Fish Hatchery ........................................... 7 Mussel Management ............................................. 6 Non-game Wildlife ........................................... -

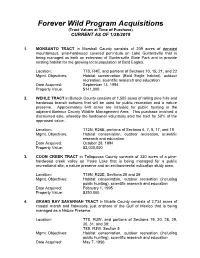

Forever Wild Program Acquisitions (Tract Values at Time of Purchase) CURRENT AS of 1/28/2019

Forever Wild Program Acquisitions (Tract Values at Time of Purchase) CURRENT AS OF 1/28/2019 1. MONSANTO TRACT in Marshall County consists of 209 acres of donated mountainous, pine-hardwood covered peninsula on Lake Guntersville that is being managed as both an extension of Guntersville State Park and to provide nesting habitat for the growing local population of Bald Eagles. Location: T7S, R4E, and portions of Sections 10, 15, 21, and 22 Mgmt. Objectives: Habitat conservation (Bald Eagle habitat), outdoor recreation, scientific research and education Date Acquired: September 13, 1994 Property Value: $141,000 2. WEHLE TRACT in Bullock County consists of 1,505 acres of rolling pine hills and hardwood branch bottoms that will be used for public recreation and a nature preserve. Approximately 640 acres are included for public hunting in the adjacent Barbour County Wildlife Management Area. This purchase involved a discounted sale, whereby the landowner voluntarily sold the tract for 50% of the appraised value. Location: T12N, R26E, portions of Sections 6, 7, 8, 17, and 18 Mgmt. Objectives: Habitat conservation, outdoor recreation, scientific research and education Date Acquired: October 28, 1994 Property Value: $2,000,000 3. COON CREEK TRACT in Tallapoosa County consists of 320 acres of a pine- hardwood creek valley on Yates Lake that is being managed for a public recreational site, a nature preserve and an environmental education study area. Location: T19N, R22E, Sections 28 and 29 Mgmt. Objectives: Habitat conservation, outdoor recreation (including public hunting), scientific research and education Date Acquired: February 1, 1995 Property Value: $350,000 4.