Transactions 1994

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Norfolk Local Flood Risk Management Strategy

Appendix A Norfolk Local Flood Risk Management Strategy Consultation Draft March 2015 1 Blank 2 Part One - Flooding and Flood Risk Management Contents PART ONE – FLOODING AND FLOOD RISK MANAGEMENT ..................... 5 1. Introduction ..................................................................................... 5 2 What Is Flooding? ........................................................................... 8 3. What is Flood Risk? ...................................................................... 10 4. What are the sources of flooding? ................................................ 13 5. Sources of Local Flood Risk ......................................................... 14 6. Sources of Strategic Flood Risk .................................................... 17 7. Flood Risk Management ............................................................... 19 8. Flood Risk Management Authorities ............................................. 22 PART TWO – FLOOD RISK IN NORFOLK .................................................. 30 9. Flood Risk in Norfolk ..................................................................... 30 Flood Risk in Your Area ................................................................ 39 10. Broadland District .......................................................................... 39 11. Breckland District .......................................................................... 45 12. Great Yarmouth Borough .............................................................. 51 13. Borough of King’s -

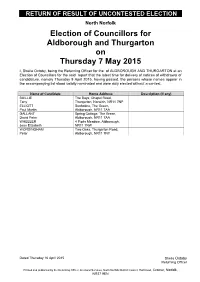

Return of Result of Uncontested Election

RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION North Norfolk Election of Councillors for Aldborough and Thurgarton on Thursday 7 May 2015 I, Sheila Oxtoby, being the Returning Officer for the of ALDBOROUGH AND THURGARTON at an Election of Councillors for the said report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 9 April 2015, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) BAILLIE The Bays, Chapel Road, Tony Thurgarton, Norwich, NR11 7NP ELLIOTT Sunholme, The Green, Paul Martin Aldborough, NR11 7AA GALLANT Spring Cottage, The Green, David Peter Aldborough, NR11 7AA WHEELER 4 Pipits Meadow, Aldborough, Jean Elizabeth NR11 7NW WORDINGHAM Two Oaks, Thurgarton Road, Peter Aldborough, NR11 7NY Dated Thursday 16 April 2015 Sheila Oxtoby Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Electoral Services, North Norfolk District Council, Holt Road, Cromer, Norfolk, NR27 9EN RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION North Norfolk Election of Councillors for Antingham on Thursday 7 May 2015 I, Sheila Oxtoby, being the Returning Officer for the of ANTINGHAM at an Election of Councillors for the said report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 9 April 2015, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) EVERSON Margra, Southrepps Road, Graham Fredrick Antingham, North Walsham, NR28 0NP JONES The Old Coach House, Antingham Independent Graham Hall, Cromer Road, Antingham, N. -

Appropriate Assessment (Submission)

June 2007 North Norfolk District Council Planning Policy Team Telephone: 01263 516318 E-Mail: [email protected] Write to: Jill Fisher, Planning Policy Manager, North Norfolk District Council, Holt Road, Cromer, NR27 9EN www.northnorfolk.org/ldf All of the LDF Documents can be made available in Braille, large print or in other languages. Please contact 01263 516321 to discuss your requirements. Core Strategy Appropriate Assessment (Submission) Contents 1 Introduction 4 2 The Appropriate Assessment Process 4 3 Consultation and Preparation 5 4 Evidence gathering for the Appropriate Assessment 6 European sites that may be affected 6 Characteristics and conservation objectives of the European sites 8 Other relevant plans or projects 25 5 Appropriate Assessment and Plan analysis 28 Tables Table 4.1 - Broadland SPA/SAC qualifying features 9 Table 4.2 - Great Yarmouth North Denes SPA/SAC 12 Table 4.3 - North Norfolk Coast SPA/SAC qualifying features 15 Table 4.4 - Norfolk Valley Fens SAC qualifying features 19 Table 4.5 - Overstrand Cliffs SAC qualifying features 21 Table 4.6 - Paston Great Barn SAC qualifying features 23 Table 4.7 - River Wensum SAC qualifying features 24 Table 4.8 - Neighbouring districts Core Strategy progress table 27 Table 5.1 - Screening for likely significant effects 29 Table 5.2 - Details of Settlements in policies SS1, SS3, SS5 and SS7 to SS14 and how policy amendments have resulted in no likely significant effects being identified 35 Maps Map 4.1 - Environmental Designations 7 Map 4.2 - Broadland Environmental -

Contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (Are Distinguished by Letter Code, Given Below) Those from 1801-13 Have Also Been Transcribed and Have No Code

Norfolk Family History Society Norfolk Marriages 1801-1837 The contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (are distinguished by letter code, given below) those from 1801-13 have also been transcribed and have no code. ASt All Saints Hel St. Helen’s MyM St. Mary in the S&J St. Simon & St. And St. Andrew’s Jam St. James’ Marsh Jude Aug St. Augustine’s Jma St. John McC St. Michael Coslany Ste St. Stephen’s Ben St. Benedict’s Maddermarket McP St. Michael at Plea Swi St. Swithen’s JSe St. John Sepulchre McT St. Michael at Thorn Cle St. Clement’s Erh Earlham St. Mary’s Edm St. Edmund’s JTi St. John Timberhill Pau St. Paul’s Etn Eaton St. Andrew’s Eth St. Etheldreda’s Jul St. Julian’s PHu St. Peter Hungate GCo St. George Colegate Law St. Lawrence’s PMa St. Peter Mancroft Hei Heigham St. GTo St. George Mgt St. Margaret’s PpM St. Peter per Bartholomew Tombland MtO St. Martin at Oak Mountergate Lak Lakenham St. John Gil St. Giles’ MtP St. Martin at Palace PSo St. Peter Southgate the Baptist and All Grg St. Gregory’s MyC St. Mary Coslany Sav St. Saviour’s Saints The 25 Suffolk parishes Ashby Burgh Castle (Nfk 1974) Gisleham Kessingland Mutford Barnby Carlton Colville Gorleston (Nfk 1889) Kirkley Oulton Belton (Nfk 1974) Corton Gunton Knettishall Pakefield Blundeston Cove, North Herringfleet Lound Rushmere Bradwell (Nfk 1974) Fritton (Nfk 1974) Hopton (Nfk 1974) Lowestoft Somerleyton The Norfolk parishes 1 Acle 36 Barton Bendish St Andrew 71 Bodham 106 Burlingham St Edmond 141 Colney 2 Alburgh 37 Barton Bendish St Mary 72 Bodney 107 Burlingham -

County Town Title Film/Fiche # Item # Norfolk Benefices, List Of

County Town Title Film/Fiche # Item # Norfolk Benefices, List of 1471412 It 44 Norfolk Census 1851 Index 6115160 Norfolk Church Records 1725-1812 1526807 It 1 Norfolk Marriage Allegations Index 1811-1825 375230 Norfolk Marriage Allegations Index 1825-1839 375231 Norfolk Marriage Allegations Index 1839-1859 375232 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1715-1734 1596461 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1734-1749 1596462 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1770-1774 1596563 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1774-1781 1596564 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1790-1797 1596566 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1798-1803 1596567 Norfolk Marriage Bonds 1812-1819 1596597 Norfolk Marriages Parish Registers 1539-1812 496683 It 2 Norfolk Probate Inventories Index 1674-1825 1471414 It 17-20 Norfolk Tax Assessments 1692-1806 1471412 It 30-43 Norfolk Wills V.101 1854-1857 167184 Norfolk Alburgh Parish Register Extracts 1538-1715 894712 It 5 Norfolk Alby Parish Records 1600-1812 1526778 It 15 Norfolk Aldeby Church Records 1725-1812 1526786 It 6 Norfolk Alethorpe Census 1841 438859 Norfolk Arminghall Census 1841 438862 Norfolk Ashby Church Records 1725-1812 1526786 It 7 Norfolk Ashby Parish Register Extracts 1646 894712 It 5 Norfolk Ashwell-Thorpe Census 1841 438851 Norfolk Aslacton Census 1841 438851 Norfolk Baconsthorpe Parish Register Extracts 1676-1770 894712 It 6 Norfolk Bagthorpe Census 1841 438859 Norfolk Bale Census 1841 438862 Norfolk Bale Parish Register Extracts 1538-1716 894712 It 6 Norfolk Barmer Census 1841 438859 Norfolk Barney Census 1841 438859 Norfolk Barton-Bendish Church Records 1725-1812 1526807 It -

Habitats Regulations Assessment of the South Norfolk Village Cluster Housing Allocations Plan

Habitats Regulations Assessment of the South Norfolk Village Cluster Housing Allocations Plan Regulation 18 HRA Report May 2021 Habitats Regulations Assessment of the South Norfolk Village Cluster Housing Allocations Plan Regulation 18 HRA Report LC- 654 Document Control Box Client South Norfolk Council Habitats Regulations Assessment Report Title Regulation 18 – HRA Report Status FINAL Filename LC-654_South Norfolk_Regulation 18_HRA Report_8_140521SC.docx Date May 2021 Author SC Reviewed ND Approved ND Photo: Female broad bodied chaser by Shutterstock Regulation 18 – HRA Report May 2021 LC-654_South Norfolk_Regulation 18_HRA Report_8_140521SC.docx Contents 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Purpose of this report ............................................................................................................................................... 1 2 The South Norfolk Village Cluster Housing Allocations Plan ................................................................... 3 2.1 Greater Norwich Local Plan .................................................................................................................................... 3 2.2 South Norfolk Village Cluster Housing Allocations Plan ................................................................................ 3 2.3 Village Clusters .......................................................................................................................................................... -

David Tyldesley and Associates Planning, Landscape and Environmental Consultants

DAVID TYLDESLEY AND ASSOCIATES PLANNING, LANDSCAPE AND ENVIRONMENTAL CONSULTANTS Habitat Regulations Assessment: Breckland Council Submission Core Strategy and Development Control Policies Document Durwyn Liley, Rachel Hoskin, John Underhill-Day & David Tyldesley 1 DRAFT Date: 7th November 2008 Version: Draft Recommended Citation: Liley, D., Hoskin, R., Underhill-Day, J. & Tyldesley, D. (2008). Habitat Regulations Assessment: Breckland Council Submission Core Strategy and Development Control Policies Document. Footprint Ecology, Wareham, Dorset. Report for Breckland District Council. 2 Summary This document records the results of a Habitat Regulations Assessment (HRA) of Breckland District Council’s Core Strategy. The Breckland District lies in an area of considerable importance for nature conservation with a number of European Sites located within and just outside the District. The range of sites, habitats and designations is complex. Taking an area of search of 20km around the District boundary as an initial screening for relevant protected sites the assessment identified five different SPAs, ten different SACs and eight different Ramsar sites. Following on from this initial screening the assessment identifies the following potential adverse effects which are addressed within the appropriate assessment: • Reduction in the density of Breckland SPA Annex I bird species (stone curlew, nightjar, woodlark) near to new housing. • Increased levels of recreational activity resulting in increased disturbance to Breckland SPA Annex I bird species (stone curlew, nightjar, woodlark). • Increased levels of people on and around the heaths, resulting in an increase in urban effects such as increased fire risk, fly-tipping, trampling. • Increased levels of recreation to the Norfolk Coast (including the Wash), potentially resulting in disturbance to interest features and other recreational impacts. -

233 08 SD50 Environment Permitting Decision Document

Environment Agency permitting decisions Bespoke permit We have decided to grant the permit for Didlington Farm Poultry Unit operated by Mr Robert Anderson, Mrs Rosamond Anderson and Mr Marcus Anderson. The permit number is EPR/EP3937EP. We consider in reaching that decision we have taken into account all relevant considerations and legal requirements and that the permit will ensure that the appropriate level of environmental protection is provided. Purpose of this document This decision document: • explains how the application has been determined • provides a record of the decision-making process • shows how all relevant factors have been taken into account • justifies the specific conditions in the permit other than those in our generic permit template. Unless the decision document specifies otherwise we have accepted the applicant’s proposals. Structure of this document • Key issues • Annex 1 the decision checklist • Annex 2 the consultation, web publicising responses. EPR/EP3937EP/A001 Page 1 of 12 Key Issues 1) Ammonia Impacts There are two Special Areas for Conservation (SAC) within 3.4km, one Special Protection Area (SPA) within 850m, seven Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) within 4.9km and six Local Wildlife Sites (LWS) within 1.4km of the facility, one of which is within 250m. Assessment of SAC and SPA If the Process Contribution (PC) is below 4% of the relevant critical level (CLe) or critical load (CLo) then the farm can be permitted with no further assessment. Initial screening using Ammonia Screening Tool (AST) v4.4 has indicated that the PC for Breckland SAC, Norfolk Valley Fens SAC and Breckland SPA is predicted to be greater than 4% of the CLe for ammonia. -

Site Improvement Plan Norfolk Valley Fens

Improvement Programme for England's Natura 2000 Sites (IPENS) Planning for the Future Site Improvement Plan Norfolk Valley Fens Site Improvement Plans (SIPs) have been developed for each Natura 2000 site in England as part of the Improvement Programme for England's Natura 2000 sites (IPENS). Natura 2000 sites is the combined term for sites designated as Special Areas of Conservation (SAC) and Special Protected Areas (SPA). This work has been financially supported by LIFE, a financial instrument of the European Community. The plan provides a high level overview of the issues (both current and predicted) affecting the condition of the Natura 2000 features on the site(s) and outlines the priority measures required to improve the condition of the features. It does not cover issues where remedial actions are already in place or ongoing management activities which are required for maintenance. The SIP consists of three parts: a Summary table, which sets out the priority Issues and Measures; a detailed Actions table, which sets out who needs to do what, when and how much it is estimated to cost; and a set of tables containing contextual information and links. Once this current programme ends, it is anticipated that Natural England and others, working with landowners and managers, will all play a role in delivering the priority measures to improve the condition of the features on these sites. The SIPs are based on Natural England's current evidence and knowledge. The SIPs are not legal documents, they are live documents that will be updated to reflect changes in our evidence/knowledge and as actions get underway. -

Garden Moth Scheme Report 2017

Garden Moth Scheme Report 2017 Heather Young – April 2018 1 GMS Report 2017 CONTENTS PAGE Introduction 2 Top 30 Species 2017 3 Scientific Publications 4 Abundant and Widespread Species 8 Common or Garden Moths 11 Winter GMS 2017-18 15 Coordination Changes 16 GMS Annual Conference 16 GMS Sponsors 17 Links & Acknowledgements 18 Cover photograph: Peppered Moth (H. Young) Introduction The Garden Moth Scheme (GMS) welcomes participants from all parts of the United Kingdom and Ireland, and in 2017 received 360 completed recording forms, an increase of over 5% on 2016 (341). We have consistently received records from over 300 sites across the UK and Ireland since 2010, and now have almost 1 ½ million records in the GMS database. Several scientific papers using the GMS data have now been published in peer- reviewed journals, and these are listed in this report, with the relevant abstracts, to illustrate how the GMS records are used for research. The GMS is divided into 12 regions, monitoring 233 species of moth in every part of the UK and Ireland (the ‘Core Species’), along with a variable number of ‘Regional Species’. A selection of core species whose name suggests they should be found commonly, or in our gardens, is highlighted in this report. There is a round-up of the 2017-18 Winter Garden Moth Scheme, which attracted a surprisingly high number of recorders (102) despite the poor weather, a summary of the changes taking place in the GMS coordination team for 2018, and a short report on the 2018 Annual Conference, but we begin as usual with the Top 30 for GMS 2017. -

Harper's Island Wetlands Butterflies & Moths (2020)

Introduction Harper’s Island Wetlands (HIW) nature reserve, situated close to the village of Glounthaune on the north shore of Cork Harbour is well known for its birds, many of which come from all over northern Europe and beyond, but there is a lot more to the wildlife at the HWI nature reserve than birds. One of our goals it to find out as much as we can about all aspects of life, both plant and animal, that live or visit HIW. This is a report on the butterflies and moths of HIW. Butterflies After birds, butterflies are probably the one of the best known flying creatures. While there has been no structured study of them on at HIW, 17 of Ireland’s 33 resident and regular migrant species of Irish butterflies have been recorded. Just this summer we added the Comma butterfly to the island list. A species spreading across Ireland in recent years possibly in response to climate change. Hopefully we can set up regular monitoring of the butterflies at HIW in the next couple of years. Butterfly Species Recorded at Harper’s Island Wetlands up to September 2020. Colias croceus Clouded Yellow Pieris brassicae Large White Pieris rapae Small White Pieris napi Green-veined White Anthocharis cardamines Orange-tip Lycaena phlaeas Small Copper Polyommatus icarus Common Blue Celastrina argiolus Holly Blue Vanessa atalanta Red Admiral Vanessa cardui Painted Lady Aglais io Peacock Aglais urticae Small Tortoiseshell Polygonia c-album Comma Speyeria aglaja Dark-green Fritillary Pararge aegeria Speckled Wood Maniola jurtina Meadow Brown Aphantopus hyperantus Ringlet Moths One group of insects that are rarely seen by visitors to HIW is the moths. -

Serving Holt, Sheringham, Wells, Fakenham And

Issue 444 Free Fortnightly 28th Feb 2020 TheThe HoltHolt www.holtchronicle.co.uk All Saints Church Sharrington by Jim Key Serving Holt, Sheringham, Wells, Fakenham and surrounding villages THE HOLT CHRONICLE The deadline for Issue 445 is Noon Tuesday 3rd March The Next Issue will be Published on 13th March 2020 Please send articles for publication, forthcoming event details, ‘For Sale’ adverts, etc. by e-mail to info@ holtchronicle.co.uk or leave in our collection box in Feeney’s Newsagents, Market Place, Holt. Your Editor is Jo who can be contacted on 01263 821463. We can also arrange DELIVERY OF LEAFLETS - delivery starts at just 3p per insertion of an A4/A5 sheet. Anthony Keeble DNHHEOHURR¿QJ#\DKRRFRXN Advertising in THE HOLT CHRONICLE could promote Director 6 Station Road your business way beyond your expectations. 07748 845143 / 01328 829152 *UHDW5\EXUJK Call Pete on 07818 653720 Don’t forget to visit our website at www.holtchronicle.co.uk 31 Church Street, Sheringham 31 Church Street, Sheringham, Holt Foot Clinic Ltd. NR26 8QS Norfolk NR26 8QS TELTEL 01263 825274825274 FAX 01263 823745823745 01263 711011 Email:[email protected] Painful Feet? WeWe can help with all foot problems. Manufacturers0DQXIDFWXUHUV 6XSSOLHUVRI & Suppliers of: WeWe provide a range of treatments ƔIRRWFDUHQDLOFXWWLQJKDUGVNLQFRUQV DQHUDFWRRIƔ VQURFQLNVGUDKJQLWWXFOLD CurtainsCurtains && CurtainCurtain Poles, Roller Blinds,Blinds, ƔELRPHFKDQLFDODVVHVVPHQWVRUWKRWLFV LQDKFHPRLEƔ VFLWRKWURVWQHPVVHVVDODF PleatedPleated Blinds, Blinds, VerticalVertical Blinds, Venetian Blinds,Blinds, ƔIRRWZHDUDGYLFH GDUDHZWRRIƔ HFLYG VisionVision Blinds Blinds, ,Perfect Perfect Fit Blinds, Fly screens, ƔLQJURZLQJWRHQDLOVQDLOVXUJHU\ RWJQLZRUJQLƔ \UHJUXVOLDQVOLDQHR WoodenWooden Shutters, Wooden Venetians,Venetians ƔKRPHYLVLWVDYDLODEOH VWLVLYHPRKƔ HOEDOLDYD DutchDutch Canopies,Canopies, Awnings $QGLI\RXMXVWQHHGDELWRISDPSHULQJZHGRWKDWWRR HQWVXMXR\ILGQ$ DKWRGHZJQLUHSPDSIRWLEDGHH RRWWD and much more...more.