David Tyldesley and Associates Planning, Landscape and Environmental Consultants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Norfolk Local Flood Risk Management Strategy

Appendix A Norfolk Local Flood Risk Management Strategy Consultation Draft March 2015 1 Blank 2 Part One - Flooding and Flood Risk Management Contents PART ONE – FLOODING AND FLOOD RISK MANAGEMENT ..................... 5 1. Introduction ..................................................................................... 5 2 What Is Flooding? ........................................................................... 8 3. What is Flood Risk? ...................................................................... 10 4. What are the sources of flooding? ................................................ 13 5. Sources of Local Flood Risk ......................................................... 14 6. Sources of Strategic Flood Risk .................................................... 17 7. Flood Risk Management ............................................................... 19 8. Flood Risk Management Authorities ............................................. 22 PART TWO – FLOOD RISK IN NORFOLK .................................................. 30 9. Flood Risk in Norfolk ..................................................................... 30 Flood Risk in Your Area ................................................................ 39 10. Broadland District .......................................................................... 39 11. Breckland District .......................................................................... 45 12. Great Yarmouth Borough .............................................................. 51 13. Borough of King’s -

Habitat Regulations Assessment: Breckland Council Submission Core Strategy and Development Control Policies

Habitats Regulation Assessment of the Site Specific Allocations & Policies Document, Wymondham Area Action Plan, Long Stratton Area Action Plan and Cringleford Neighbourhood Development Plan, undertaken for South Norfolk Council October 2013 Natural Environment Team HRA of Site Allocations Document, Wymondham AAP, Long Stratton AAP and Cringleford Neighbourhood Plan for South Norfolk Council October 2013 Habitats Regulation Assessment of the Site Specific Allocations and Policies Document, the Wymondham Area Action Plan, the Long Stratton Area Action Plan and the Cringleford Neighbourhood Development Plan Executive Summary As required by the Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2010, before deciding to give consent or permission for a plan or project which is likely to have a significant effect on a European site, either alone or in combination with other plans or projects, the competent authority is required to make an appropriate assessment of the implications for that site in view of that site’s conservation objectives. This document is a record of the Habitats Regulation Assessment of the Sites Allocation Document, undertaken for South Norfolk Council. Additionally, proposed development at Wymondham, as described in the emerging Wymondham Area Action Plan, at Long Stratton, as described in the emerging Long Stratton Area Action Plan and proposed housing in the parish of Cringleford, guided by the emerging Cringleford Draft Neighbourhood Plan, are assessed Three groups of plans are reviewed with respect to their conclusions with respect to potential in-combination effects. These are plans for The Greater Norwich Development Partnership, Great Yarmouth Borough Council, Breckland District Council, and The Broads Authority including local development plans and the Tourism Strategy. -

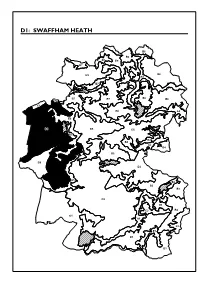

D1: Swaffham Heath

D1: SWAFFHAM HEATH B6 B6 B7 E9 B7 E9 B6 A4 B7 F1 B7 E7 E8 B6 F1 F1 B6 A5 E6 D1 B5 E5 B5 B4 B4 A2 B4 B5 B8 E4 A3 B2 B3 E3 D2 D3 E2 B2 C1 A1 E2 E1 D3 B1 D1: SWAFFHAM HEATH Location and Boundaries D1.1 A large area of the Breckland Heathland with Plantation landscape type located to the north-west, west and south west of Swaffham, with character defined primarily by the land use of arable farmland, historic parklands and plantation woodland and distinctive Scot’s pine belts. To the north the character area boundary is marked by the adjacent River Nar character area and to the west by the district boundary and a change in character to a more settled area of farmland and plantations. To the south and east the landform falls towards the River Wissey. Key Characteristics • Drift deposits of sand, clay and gravel create a gently undulating landscape, with topography ranging from 10-70m AOD across the character area. • Free draining sandy soils support the functional land cover of arable cultivation, pig farming and plantation woodland. • Ancient, contorted scots pine shelterbelts and screening belts of trees provide shelter to the easily eroded brown soils and are a prominent landscape feature. • At Cockleycley Heath and Swaffham Heath, the woodland plantation blocks create a visually prominent feature in the landscape. • The large scale arable fields are delineated by hedgerows in variable condition from occasional species rich intact hedgerows with hedgerow trees, thorn hedges and pine lines. • Breckland Farmland SSSI covers a large part of the character area – the cultivated land proving a habitat for stone curlew. -

Forest Heath District Council

Forest Heath District Council Single Issue Review Policy CS7 of the Core Strategy Document Habitats Regulations Assessment, (HRA), Screening Stage July 2012 Contents 1. Introduction 1.1 Overview of the process to date 1.2 Background to Habitats Regulations Assessment 1.3 Outline of Habitats Regulations Assessment process 1.4 Introduction to the HRA screening process 2. European sites potentially affected by the Single Issue Review 3. Baseline conditions affecting European sites 4. Is it necessary to proceed to the next HRA stage? Which aspects of the document require further assessment? 4.1 Screening of the Single Issue Review 1 1. Introduction 1.1 Overview of the process to date: In order to ensure that the Single Issue Review is compliant with the requirements of the Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2010, Forest Heath District Council has embarked upon an assessment of the ‘Reviews’ implications for European wildlife sites, i.e. a Habitats Regulations Assessment of the plan. This report sets out the first stage of the HRA process for the Single Issue Review, the Screening Stage. To establish if the ‘Review’ is likely to have a significant adverse effect on any European sites it is necessary to consider evidence contained in the original HRA of the Forest Heath Core Strategy DPD that was produced in March 2009. For a number of policies within the Core Strategy, including the original Policy CS7, it was considered either that significant effects would be likely, or that a precautionary approach would need to be taken as it could not be determined that those particular plan policies would not be likely to have a significant effect upon any European Site. -

Habitats Regulations Assessment of the South Norfolk Village Cluster Housing Allocations Plan

Habitats Regulations Assessment of the South Norfolk Village Cluster Housing Allocations Plan Regulation 18 HRA Report May 2021 Habitats Regulations Assessment of the South Norfolk Village Cluster Housing Allocations Plan Regulation 18 HRA Report LC- 654 Document Control Box Client South Norfolk Council Habitats Regulations Assessment Report Title Regulation 18 – HRA Report Status FINAL Filename LC-654_South Norfolk_Regulation 18_HRA Report_8_140521SC.docx Date May 2021 Author SC Reviewed ND Approved ND Photo: Female broad bodied chaser by Shutterstock Regulation 18 – HRA Report May 2021 LC-654_South Norfolk_Regulation 18_HRA Report_8_140521SC.docx Contents 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Purpose of this report ............................................................................................................................................... 1 2 The South Norfolk Village Cluster Housing Allocations Plan ................................................................... 3 2.1 Greater Norwich Local Plan .................................................................................................................................... 3 2.2 South Norfolk Village Cluster Housing Allocations Plan ................................................................................ 3 2.3 Village Clusters .......................................................................................................................................................... -

Landscape Character Assessment Documents 2

Norfolk Vanguard Offshore Wind Farm Landscape Character Assessment Documents 2. Breckland District Part 1 of 5 Applicant: Norfolk Vanguard Limited Document Reference: ExA; ISH; 10.D3.1E 2.1 Deadline 3 Date: February 2019 Photo: Kentish Flats Offshore Wind Farm May 2007 Breckland District Landscape Character Assessment Final Report for Breckland District Council by Land Use Consultants LANDSCAPE CHARACTER ASSESSMENT OF BRECKLAND DISTRICT Final Report Prepared for Breckland Council by Land Use Consultants May 2007 43 Chalton Street London NW1 1JD Tel: 020 7383 5784 Fax: 020 7383 4798 [email protected] CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................... 1 PART 1: OVERVIEW 1. Introduction ......................................................................................... 1 The landscape of Breckland...................................................................................................................... 1 Purpose of the report................................................................................................................................ 1 Structure of the report ............................................................................................................................. 1 2. Method Statement.............................................................................. 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Data collation -

Circular Walks East Norfolk Coast Introduction

National Trail 20 Circular Walks East Norfolk Coast Introduction The walks in this guide are designed to make the most of the please be mindful to keep dogs under control and leave gates as natural beauty and cultural heritage of the Norfolk coast. As you find them. companions to stretch one and two of the Norfolk Coast Path (part of the England Coast Path), they are a great way to delve Equipment deeper into this historically and naturally rich area. A wonderful Depending on the weather, some sections of these walks can array of landscapes and habitats await, many of which are be muddy. Even in dry weather, a good pair of walking boots or home to rare wildlife. The architectural landscape is expansive shoes is essential for the longer routes. Norfolk’s climate is drier too. Churches dominate, rarely beaten for height and grandeur than much of the country but unfortunately we can’t guarantee among the peaceful countryside of the coastal region, but sunshine, so packing a waterproof is always a good idea. If you there’s much more to discover. are lucky enough to have the weather on your side, don’t forget From one mile to nine there’s a walk for everyone here, whether sun cream and a hat. you’ve never walked in the countryside before or you’re a Other considerations seasoned rambler. Many of these routes lend themselves well to The walks described in these pages are well signposted on the trail running too. With the Cromer ridge providing the greatest ground, and detailed downloadable maps are available for elevation of anywhere in East Anglia, it’s a great way to get fit as each at www.norfolktrails.co.uk. -

Habitats Regulation Assessment East Cambridgeshire Local Plan

Habitats Regulation Assessment East Cambridgeshire Local Plan June 2018 (Supersedes the November 2017 Screening Report) Contents Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................... 1 Non-Technical Summary .................................................................................................................. 1 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 1 Background to the East Cambridgeshire Local Plan ..................................................................... 1 Key Components of the Emerging East Cambridgeshire Local Plan ............................................. 2 Potential Impacts Arising from the Local Plan ............................................................................... 5 Report Purpose and Overview ...................................................................................................... 6 2. Habitats Regulation Assessment - Legislation and Requirements ................................................ 8 HRA Guidance and Best Practice ................................................................................................. 8 Main Stages of HRA ..................................................................................................................... 9 Consultation with Natural England ............................................................................................. -

Marriott's Way Circular Route Guide

MARRIOTT’S WAY CIRCULAR ROUTE GUIDE WELCOME TO MARRIOTT’S WAY MARRIOTT’S WAY is a 26-mile linear trail for riders, walkers and cyclists. Opened in 1991, it follows part of the route of two former Victorian railway lines, The Midland and Great Northern (M&GN) and Great Eastern Railway (GER). It is named in honour of William Marriott, who was chief engineer and manager of the M&GN for 41 years between 1883 and 1924. Both lines were established in the 1880s to transport passengers, livestock and industrial freight. The two routes were joined by the ‘Themelthorpe Curve’ in 1960, which became the sharpest bend on the entire British railway network. Use of the lines reduced after the Second World War. Passenger traffic ceased in 1959, but the transport of concrete ensured that freight trains still used the lines until 1985. The seven circular walks and two cycle loops in this guide encourage you to head off the main Marriott’s Way route and explore the surrounding areas that the railway served. Whilst much has changed, there’s an abundance of hidden history to be found. Many of the churches, pubs, farms and station buildings along these circular routes would still be familiar to the railway passengers of 100 years ago. 2 Marriott’s Way is a County Wildlife Site and passes through many interesting landscapes rich in wonderful countryside, wildlife, sculpture and a wealth of local history. The walks and cycle loops described in these pages are well signposted by fingerposts and Norfolk Trails’ discs. You can find all the circular trails in this guide covered by OS Explorer Map 238. -

Norfolk Boreas Offshore Wind Farm Appendix 22.14 Norfolk Vanguard Onshore Ecology Consultation Responses

Norfolk Boreas Offshore Wind Farm Appendix 22.14 Norfolk Vanguard Onshore Ecology Consultation Responses Preliminary Environmental Information Report Volume 3 Author: Royal HaskoningDHV Applicant: Norfolk Boreas Limited Document Reference: PB5640-005-2214 Date: October 2018 Photo: Ormonde Offshore Wind Farm Date Issue Remarks / Reason for Issue Author Checked Approved No. 20/07/18 01D First draft for Norfolk Boreas Limited review GC CD DT 20/09/18 01F Final for PEIR submission GC CD AD/JL Preliminary Environmental Information Report Norfolk Boreas Offshore Wind Farm PB5640-005-2214 October 2018 Page i Table of Contents 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................... 1 2 Consultation responses Norfolk Vanguard ............................................................... 1 3 References ........................................................................................................... 27 Preliminary Environmental Information Report Norfolk Boreas Offshore Wind Farm PB5640-005-2214 October 2018 Page ii Tables Table 2.1 Norfolk Vanguard Consultation Responses 2 Preliminary Environmental Information Report Norfolk Boreas Offshore Wind Farm PB5640-005-2214 October 2018 Page iii Glossary of Acronyms CoCP Code of Construction Practice DCO Development Consent Order EIA Environmental Impact Assessment ES Environmental Statement ETG Expert Topic Group HVAC High Voltage Alternating Current HVDC High Voltage Direct Current PEIR Preliminary Environmental Information Report SoS Secretary of State Preliminary Environmental Information Report Norfolk Boreas Offshore Wind Farm PB5640-005-2214 October 2018 Page iv This page is intentionally blank. Preliminary Environmental Information Report Norfolk Boreas Offshore Wind Farm PB5640-005-2214 October 2018 Page v 1 Introduction 1. Consultation is a key driver of the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) process, and throughout the lifecycle of the project, from the initial stages through to consent and post-consent. 2. -

233 08 SD50 Environment Permitting Decision Document

Environment Agency permitting decisions Bespoke permit We have decided to grant the permit for Didlington Farm Poultry Unit operated by Mr Robert Anderson, Mrs Rosamond Anderson and Mr Marcus Anderson. The permit number is EPR/EP3937EP. We consider in reaching that decision we have taken into account all relevant considerations and legal requirements and that the permit will ensure that the appropriate level of environmental protection is provided. Purpose of this document This decision document: • explains how the application has been determined • provides a record of the decision-making process • shows how all relevant factors have been taken into account • justifies the specific conditions in the permit other than those in our generic permit template. Unless the decision document specifies otherwise we have accepted the applicant’s proposals. Structure of this document • Key issues • Annex 1 the decision checklist • Annex 2 the consultation, web publicising responses. EPR/EP3937EP/A001 Page 1 of 12 Key Issues 1) Ammonia Impacts There are two Special Areas for Conservation (SAC) within 3.4km, one Special Protection Area (SPA) within 850m, seven Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) within 4.9km and six Local Wildlife Sites (LWS) within 1.4km of the facility, one of which is within 250m. Assessment of SAC and SPA If the Process Contribution (PC) is below 4% of the relevant critical level (CLe) or critical load (CLo) then the farm can be permitted with no further assessment. Initial screening using Ammonia Screening Tool (AST) v4.4 has indicated that the PC for Breckland SAC, Norfolk Valley Fens SAC and Breckland SPA is predicted to be greater than 4% of the CLe for ammonia. -

Coarse Fishing Close Season on English Rivers

Coarse fishing close season on English rivers Appendix 1 – Current coarse fish close season arrangements The close season on different waters In England, there is a coarse fish close season on all rivers, some canals and some stillwaters. This has not always been the case. In the 1990s, only around 60% of the canal network had a close season and in some regions, the close season had been dispensed with on all stillwaters. Stillwaters In 1995, following consultation, government confirmed a national byelaw which retained the coarse fish close season on rivers, streams, drains and canals, but dispensed with it on most stillwaters. The rationale was twofold: • Most stillwaters are discrete waterbodies in single ownership. Fishery owners can apply bespoke angling restrictions to protect their stocks, including non-statutory close times. • The close season had been dispensed with on many stillwaters prior to 1995 without apparent detriment to those fisheries. This presented strong evidence in favour of removing it. The close season is retained on some Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs) and the Norfolk and Suffolk Broads, as a precaution against possible damage to sensitive wildlife - see Appendix 1. This consultation is not seeking views on whether the close season should be retained on these stillwaters While most stillwater fishery managers have not re-imposed their own close season rules, some have, either adopting the same dates as apply to rivers or tailoring them to their waters' specific needs. Canals The Environment Agency commissioned a research project in 1997 to examine the evidence around the close season on canals to identify whether or not angling during the close season was detrimental to canal fisheries.