Rails-With-Trails: Lessons Learned Literature Review, Current Practices, Conclusions TMC3/BB252 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Laurel Highlands Pennsylvania

The LaureL highLands pennsylvania 2010 Travel Guide a place of WONDER You really should be here! Make New Family Memories Seven Springs Mountain Resort is the perfect place to reconnect and make a new memory with your family and friends! Whether the snow is blanketing the ground, the leaves are gilded in rich autumn hues or the sun is shining and there is a warm summer breeze, Seven Springs is your escape destination. At Pennsylvania’s largest resort, you can unwind at Trillium Spa, take a shot at sporting clays, explore 285 acres of skiable terrain, enjoy the adrenaline rush of a snowmobile tour – the opportunities are endless! At Seven Springs, we strive to provide you and yours with legendary customer service, value and warm lifelong memories. What are you waiting for? You really should be here! Seasonal packages available year-round - call 800.452.2223 or visit us on line at www.7Springs.com. Seven Springs Mountain Resort 777 Waterwheel Drive | Seven Springs, PA 15622 800.452.2223 | www.7Springs.com s you look through the 2010 Laurel AHighlands Travel Guide, you may notice the question, have you ever wondered, used a lot! Have you ever wondered what it would be like to 1won-der: \wən-dər\ n 1 a: a cause of astonishment or admiration: marvel b: miracle 2 : the quality of exciting amazed admiration 3 a : rapt attention or astonishment at something awesomely mysterious or new to one’s experience 2won-der: v won·dered; won·der·ing 1 a : to be in a state of wonder b : to feel surprise 2 : to feelhave curiosity oryou doubt 3 won-derever: adj WONDERED? wondrous, wonderful: as a : exciting amazement or admiration b : effective or efficient far beyond anything previously known or anticipated. -

Warner Spur Multi-Use Trail Master Plan

Warner Spur Multi-Use Trail Master Plan Chester County Tredyffrin Township Prepared by: December 2019 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Prepared for the In partnership with Tredyffrin Township Chester County Board of Commissioners Plan Advisory Committee Michelle Kichline Zachary Barner, East Whiteland Township Kathi Cozzone Mahew Baumann, Tredyffrin Township Terence Farrell Les Bear, Indian Run Road Association Stephen Burgo, Tredyffrin Township Carol Clarke, Great Valley Association Consultants Rev. Abigail Crozier Nestlehu, St. Peter's Church McMahon Associates, Inc. Jim Garrison, Vanguard In association with Jeff Goggins, Trammel Crow Advanced GeoServices, Corp. Rachael Griffith, Chester County Planning Commission Glackin Thomas Panzak, Inc. Amanda Lafty, Tredyffrin Township Transportation Management Association of Tim Lander, Open Land Conservancy of Chester County Chester County (TMACC) William Martin, Tredyffrin Township Katherine McGovern, Indian Run Road Association Funding Aravind Pouru, Atwater HOA Dave Stauffer, Chester County Department of Facilities and Parks Grant funding provided from the William Penn Brian Styche, Chester County Planning Commission Foundation through the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission’s Regional Trails Program. Warner Spur Multi-Use Trail Master Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 | Background 3 | Conceptual Improvement Plan Introduction 1-1 Conceptual Improvement Plan 3-1 History and Previous Plans 1-1 Conceptual Design Exhibits for Key 3-8 Connections and Crossings Study Area 1-2 Public and Emergency -

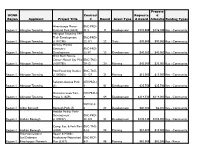

Keystone Fund Projects by Applicant (1994-2017) Propose DCNR Contract Requeste D Region Applicant Project Title # Round Grant Type D Award Allocatio Funding Types

Keystone Fund Projects by Applicant (1994-2017) Propose DCNR Contract Requeste d Region Applicant Project Title # Round Grant Type d Award Allocatio Funding Types Alverthorpe Manor BRC-PRD- Region 1 Abington Township Cultural Park (6422) 11-3 11 Development $223,000 $136,900 Key - Community Abington Township TAP Trail- Development BRC-PRD- Region 1 Abington Township (1101296) 22-171 22 Trails $90,000 $90,000 Key - Community Ardsley Wildlife Sanctuary- BRC-PRD- Region 1 Abington Township Development 22-37 22 Development $40,000 $40,000 Key - Community Briar Bush Nature Center Master Site Plan BRC-TAG- Region 1 Abington Township (1007785) 20-12 20 Planning $42,000 $37,000 Key - Community Pool Feasibility Studies BRC-TAG- Region 1 Abington Township (1100063) 21-127 21 Planning $15,000 $15,000 Key - Community Rubicam Avenue Park KEY-PRD-1- Region 1 Abington Township (1) 1 01 Development $25,750 $25,700 Key - Community Demonstration Trail - KEY-PRD-4- Region 1 Abington Township Phase I (1659) 4 04 Development $114,330 $114,000 Key - Community KEY-SC-3- Region 1 Aldan Borough Borough Park (5) 6 03 Development $20,000 $2,000 Key - Community Ambler Pocket Park- Development BRC-PRD- Region 1 Ambler Borough (1102237) 23-176 23 Development $102,340 $102,000 Key - Community Comp. Rec. & Park Plan BRC-TAG- Region 1 Ambler Borough (4438) 8-16 08 Planning $10,400 $10,000 Key - Community American Littoral Upper & Middle Soc/Delaware Neshaminy Watershed BRC-RCP- Region 1 Riverkeeper Network Plan (3337) 6-9 06 Planning $62,500 $62,500 Key - Rivers Keystone Fund Projects by Applicant (1994-2017) Propose DCNR Contract Requeste d Region Applicant Project Title # Round Grant Type d Award Allocatio Funding Types Valley View Park - Development BRC-PRD- Region 1 Aston Township (1100582) 21-114 21 Development $184,000 $164,000 Key - Community Comp. -

Appendix IV: Regional Vision Project Lists for Southwestern Pennsylvania

Appendix IV: Regional Vision Project Lists for Southwestern Pennsylvania IV-2: Projects Currently Beyond Fiscal Capacity Appendix IV-2: Projects Currently Beyond Fiscal Capacity The following projects are consistent with the Regional Vision of a world-class, safe and well maintained transportation system that provides mobility for all, enables resilient communities, and supports a globally competitive economy. While beyond current fiscal capacity, these projects would contribute to achievement of the Regional Vision. They are listed herein to illustrate additional priority projects in need of funding. Project Type Project Allegheny Port Authority of Allegheny West Busway BRT Extension – Downtown to County Pittsburgh International Airport Extend East Busway to Monroeville (including Braddock, East Pittsburgh, Turtle Creek) Improved Regional Transit Connection Facilities Enhanced Rapid Transit Connection – Downtown to North Hills Technological Improvements New Maintenance Garage for Alternative Fuel Buses Purchase of 55 New LRT Vehicles Park and Ride – Additional Capacity Pittsburgh International Airport Enlow Airport Access Road Related New McClaren Road Bridge High Quality Transit Service and Connections Clinton Connector US 30 and Clinton Road: Intersection Improvements Roadway / Bridge SR 28: Reconstruction PA 51: Flooding – Liberty Tunnel to 51/88 Intersection SR 22 at SR 48: Reconstruction and Drainage SR 837: Reconstruction SR 22/30: Preservation to Southern Beltway SR 88: Reconstruction – Conner Road to South Park SR 351: Reconstruction SR 3003 (Washington Pike): Capacity Upgrades SR 3006: Widening – Boyce Road to Route 19 Project Type Project Waterfront Access Bridge: Reconstruction Elizabeth Bridge: Preservation Glenfield Bridge: Preservation I-376: Bridge Preservation over Rodi Road Kennywood Bridge: Deck Replacement – SR 837 over Union RR Hulton Road Bridge: Preservation 31st Street Bridge: Preservation Liberty Bridge: Preservation Marshall Avenue Interchange: Reconstruction 7th and 9th St. -

Heritage Rail Trail Feasibility Study 2017

TOWN OF DEDHAM HERITAGE RAIL TRAIL FEASIBILITY STUDY 2017 PLANNING DEPARTMENT + ENVIRONMENTAL DEPARTMENT ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We gratefully recognize the Town of Dedham’s dedicated Planning and Environmental Department’s staff, including Richard McCarthy, Town Planner and Virginia LeClair, Environmental Coordinator, each of whom helped to guide this feasibility study effort. Their commitment to the town and its open space system will yield positive benefits to all as they seek to evaluate projects like this potential rail trail. Special thanks to the many representatives of the Town of Dedham for their commitment to evaluate the feasibility of the Heritage Rail Trail. We also thank the many community members who came out for the public and private forums to express their concerns in person. The recommendations contained in the Heritage Rail Trail Feasibility Study represent our best professional judgment and expertise tempered by the unique perspectives of each of the participants to the process. Cheri Ruane, RLA Vice President Weston & Sampson June 2017 Special thanks to: Virginia LeClair, Environmental Coordinator Richard McCarthy, Town Planner Residents of Dedham Friends of the Dedham Heritage Rail Trail Dedham Taxpayers for Responsible Spending Page | 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction and Background 2. Community Outreach and Public Process 3. Base Mapping and Existing Conditions 4. Rail Corridor Segments 5. Key Considerations 6. Preliminary Trail Alignment 7. Opinion of Probable Cost 8. Phasing and Implementation 9. Conclusion Page | 2 Introduction and Background Weston & Sampson was selected through a proposal process by the Town of Dedham to complete a Feasibility Study for a proposed Heritage Rail Trail in Dedham, Massachusetts. -

Susquehanna Greenway & Trail Authority Case Study, August 2014

Susquehanna Greenway & Trail Authority Case Study August 2014 Susquehanna Greenway Partnership Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 1 Trail Organization Types ............................................................................................................................... 3 Advantages and Disadvantages of Trail Ownership Structures .................................................................. 21 Trail Maintenance ....................................................................................................................................... 23 Potential Cost‐Sharing Options ................................................................................................................... 25 Potential Sources and Uses ......................................................................................................................... 27 Economic Benefits ....................................................................................................................................... 32 Two‐County, Three‐County, and Five‐County Draft Budget Scenarios ...................................................... 38 Recommendations ...................................................................................................................................... 54 Attachment 1 ............................................................................................................................................. -

America's Rails-With-Trails

America’s Rails-with-Trails A Resource for Planners, Agencies and Advocates on Trails Along Active Railroad Corridors About Rails-to-Trails Conservancy Rails-to-Trails Conservancy (RTC) has helped develop more than 21,000 miles of rail-trail throughout the country and provide technical assistance for thousands of miles of potential rail-trails waiting to be built. Serving as the national voice for more than 100,000 members and supporters, RTC has supported the tremendous growth and development of rail-trails since opening our doors on February 1, 1986, and remains dedicated to the creation of a nationwide network of trails and connecting corridors. RTC is committed to enhancing the health of America’s environment, transportation, economy, neighborhoods and people — ensuring a better future made possible by trails and the connections they inspire. Orange Heritage Trail, N.Y. (Boyd Loving) Acknowledgements The team wishes to recognize and thank RTC staff who contributed to the accuracy and utility of this report: Barbara Richey, graphic designer, Jake Lynch, editor, and Tim September 2013 Rosner, GIS specialist. Report produced by Rails-to-Trails The team is also grateful for the support of other RTC staff and interns who assisted Conservancy with research and report production: LEAD AUTHORS: Priscilla Bocskor, Jim Brown, Jesse Cohn, Erin Finucane, Eileen Miller, Sophia Kuo Kelly Pack, Director of Trail Development Tiong, Juliana Villabona, and Mike Vos Pat Tomes, Program Manager, RTC extends its gratitude to the trail managers and experts who shared their Northeast Regional Office knowledge to strengthen this report. A complete list of interview and survey participants is included in the Appendix, which is available online at www. -

RWT Section 3

SECTION III: RWT Development Process The current RWT development process varies from location to location, although com Blackstone River Bikeway, mon elements exist. Trail advocacy groups and public agencies often initially identify a Albion, RI desired RWT as part of a bikeway master plan. They then work to secure funding prior to initiating contact with the affected railroad. “As a general rule, bike When a public agency seeks approval of an RWT, the railroad company typically lacks an es tablished, accessible review and approval process. While some RWTs move forward quickly trails should not be (typically those where the trail development agency owns the land), many more are outright located along railroad rejected or involve a lengthy, contentious process. RWT processes typically take between rights-of-way…[we] should three and ten years from concept to construction. not encourage recreational Overview of Recommendations use next to active [railroad] Based on the research conducted for this report, the following recommendations are made rights-of-way.” regarding RWT development processes: DEBORAH SEDARES, PROVIDENCE AND WORCESTER RAILROAD, MA 1. Local or regional bikeway or trail plans should include viable alternatives to any trail that is proposed within an active railroad corridor. 2. Each proposed RWT project should undergo a comprehensive feasibility study. If “The biggest driver was the required, the proposed project also should undergo an independent, comprehensive realization that this was a environmental review. historic transportation 3. Trail agencies must involve the railroad throughout the process and work to address corridor…to put another their safety, capacity, and liability concerns. mode into this old corridor 4. -

April 2018 GUIDEBOOK for Pennsylvania's Metropolitan Planning Organizations and Rural Planning Organizations

GUIDEBOOK FOR Pennsylvania's Metropolitan Planning Organizations and Rural Planning Organizations April 2018 GUIDEBOOK FOR Pennsylvania's Metropolitan Planning Organizations and Rural Planning Organizations TABLE OF CONTENTS chapTer 1 - Transportation Planning A. Purpose of the Guidebook....................................................................................................................................................1 xii. Congestion Management Plan.......................................................................................................................................34 B. History of Transportation Planning..............................................................................................................................1 xiii. Roadway Functional Classification Review..............................................................................................................34 C. Federal Authority and Role..................................................................................................................................................5 xiv. Annual Listing of Obligated Projects...........................................................................................................................34 i. Federal Highway Administration (FHWA).........................................................................................................................5 xv. Public Participation Plan for Statewide Planning...............................................................................................35 -

Abandoned Railroad Corridors in Kentucky

KTC-03-31/MSC1-01-1F Abandoned Railroad Corridors in Kentucky: An Inventory and Assessment Kentucky Department for Local Government June 2003 Prepared by the Kentucky Transportation Center 1. Report No. 12. Government Accession 3. Recipients catalog no KTC-03-31/MSC 1-0 1-1F No. 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date June 2003 Abandoned Railroad Corridors in Kentucky: An Inventory and Assessment 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Lisa Rainey Brownell KTC-03-31/MSC1-01-1F Kentucky Transportation Center 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) 9. Performing Organization Name and Address Kentucky Transportation Center 11. Contract or Grant No. University of Kentucky Oliver H. Raymond Building Lexington. KY 40506-0281 12. Sponsoring Agency Code 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Department for Local Governments Final 1024 Capital Center Dr. Ste. 340 Frankfort, KY 40601 14. Sponsoring Agency Code 15. Supplementary Notes 16. Abstract This report provides an inventory of Kentucky's abandoned rail lines and a detailed assessment to highlight the lines that may be the most suitable for future trail use. A secondary purpose of the report was to inventory historic railroad structures. Over 125 different abandoned rail lines were identified, mapped using GIS technology, and assessed for their current use and condition. These abandoned rights of way exist in all regions of the state, in urban and rural areas. 17. Key Words 18. Distribution Statement Abandoned Railroads, Rails to Trails Unlimited 19. Security Classif. (of this report) 120. Security Classif. (of this page) 121. No. of Pages 122. -

New Horizons ~ a County-Wide Greenway and Blueway Network

New Horizons A County-Wide Greenways and Blueways Network Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania a companion document to the County’s comprehensive land use, parks, recreation and open space planning efforts Prepared for: Westmoreland County Department of Planning & Development Westmoreland County Bureau of Parks and Recreation The Smart Growth Partnership of Westmoreland County Prepared by: Environmental Planning and Design, LLC Spring 2008 Resolution Resolution PLACEHOLDER COUNTY OF WESTMORELAND, PENNSYLVANIA RESOLUTION NO. ______ New Horizons i Resolution ii Westmoreland County Greenways and Blueways Plan Acknowledgments Acknowledgements This project was financed in part by a grant from the Community Conservation Partnership Program, Environmental Stewardship Fund, under the administration of the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Bureau of Recreation and Conservation. This project was made possible through the time, efforts and expertise of the following project stakeholders: Citizens Advisory Board Dr. Ed Lewis, Chairman Marty Mateer McGuire Jeanne Ashley Angela Rose-O’Brien Barbara Ferrier, Ph.D. Kris Samloff John Framel Patty Sutherland Dave Hawk John Ward Nancy Kukovich Randy Stas Roy Lenhardt Dr. Nick Senuta Westmoreland County Matt Bruno, Asst. Program Coordinator, Bureau of Parks and Recreation Dan Carpenter, Program Coordinator, Bureau of Parks and Recreation Wayne Johnson, Maintenance Coordinator, Bureau of Parks and Recreation Larry Larese, Executive Director, Department of Planning and Development -

America's Rails-With-Trails

America’s Rails-with-Trails A Resource for Planners, Agencies and Advocates on Trails Along Active Railroad Corridors About Rails-to-Trails Conservancy Rails-to-Trails Conservancy (RTC) has helped develop more than 21,000 miles of rail-trail throughout the country and provide technical assistance for thousands of miles of potential rail-trails waiting to be built. Serving as the national voice for more than 100,000 members and supporters, RTC has supported the tremendous growth and development of rail-trails since opening our doors on February 1, 1986, and remains dedicated to the creation of a nationwide network of trails and connecting corridors. RTC is committed to enhancing the health of America’s environment, transportation, economy, neighborhoods and people – ensuring a better future made possible by trails and the connections they inspire. Orange Heritage Trail, N.Y. (Boyd Loving) Acknowledgements The team wishes to recognize and thank RTC staff who contributed to the accuracy and utility of this report: Barbara Richey, graphic designer, Jake Lynch, editor, and Tim September 2013 Rosner, GIS specialist. Report produced by Rails-to-Trails The team is also grateful for the support of other RTC staff and interns who assisted Conservancy (RTC): with research and report production: Kelly Pack Priscilla Bocskor, Jim Brown, Jesse Cohn, Erin Finucane, Eileen Miller, Sophia Kuo Pat Tomes Tiong, Juliana Villabona, and Mike Vos Barry Bergman RTC extends its gratitude to the trail managers and experts who shared their Patrick Donaldson knowledge to strengthen this report. A complete list of interview and survey Eli Griffen participants is included in the Appendix, which is available online at www.