The Coins of Purugupta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Succession After Kumaragupta I

Copyright Notice This paper has been accepted for publication by the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, which is published by Cambridge University Press. A final version of the article will be appearing in the JRAS in 2014. 1 The Succession after Kumāragupta I Pankaj Tandon1 Most dynastic lists of the Gupta kings state that Kumāragupta I was succeeded by Skandagupta. However, it is widely accepted that Skandagupta did not accede to the throne peacefully. Nor is it certain that the succession was immediate, since there is a gap between the known dates of Kumāragupta’s and Skandagupta’s reigns. This paper is concerned with the events following the death of Kumāragupta, using numismatic evidence as the primary source, and inscriptional and other epigraphic evidence as further support. Some of the numismatic evidence is new, and even the evidence that is not new has so far received little attention in the literature on the succession after Kumāragupta. Questions are raised about one particular theory that is presently enjoying some currency, that Skandagupta was challenged primarily by his uncle Ghaṭotkacagupta. Some other possible scenarios for the political events in the period after the death of Kumāragupta I will then be proposed and analyzed. Most authors agree that Skandagupta was not the rightful heir to the throne. While he does announce himself on his inscriptions as the son of Kumāragupta I, his mother is not identified by name in any known text or inscription,2 suggesting that he was, at best, the son of a minor queen of Kumāragupta, or more probably the son of a woman who was not a queen at all. -

Gupta Empire and Their Rulers – History Notes

Gupta Empire and Their Rulers – History Notes Posted On April 28, 2020 By Cgpsc.Info Home » CGPSC Notes » History Notes » Gupta Empire and Their Rulers Gupta Empire and Their Rulers – The Gupta period marks the important phase in the history of ancient India. The long and e¸cient rule of the Guptas made a huge impact on the political, social and cultural sphere. Though the Gupta dynasty was not widespread as the Maurya Empire, but it was successful in creating an empire that is signiÛcant in the history of India. The Gupta period is also known as the “classical age” or “golden age” because of progress in literature and culture. After the downfall of Kushans, Guptas emerged and kept North India politically united for more than a century. Early Rulers of Gupta dynasty (Gupta Empire) :- Srigupta – I (270 – 300 C.E.): He was the Ûrst ruler of Magadha (modern Bihar) who established Gupta dynasty (Gupta Empire) with Pataliputra as its capital. Ghatotkacha Gupta (300 – 319 C.E): Both were not sovereign, they were subordinates of Kushana Rulers Chandragupta I (319 C.E. to 335 C.E.): Laid the foundation of Gupta rule in India. He assumed the title “Maharajadhiraja”. He issued gold coins for the Ûrst time. One of the important events in his period was his marriage with a Lichchavi (Kshatriyas) Princess. The marriage alliance with Kshatriyas gave social prestige to the Guptas who were Vaishyas. He started the Gupta Era in 319-320C.E. Chandragupta I was able to establish his authority over Magadha, Prayaga,and Saketa. Calendars in India 58 B.C. -

The Gupta Empire: an Indian Golden Age the Gupta Empire, Which Ruled

The Gupta Empire: An Indian Golden Age The Gupta Empire, which ruled the Indian subcontinent from 320 to 550 AD, ushered in a golden age of Indian civilization. It will forever be remembered as the period during which literature, science, and the arts flourished in India as never before. Beginnings of the Guptas Since the fall of the Mauryan Empire in the second century BC, India had remained divided. For 500 years, India was a patchwork of independent kingdoms. During the late third century, the powerful Gupta family gained control of the local kingship of Magadha (modern-day eastern India and Bengal). The Gupta Empire is generally held to have begun in 320 AD, when Chandragupta I (not to be confused with Chandragupta Maurya, who founded the Mauryan Empire), the third king of the dynasty, ascended the throne. He soon began conquering neighboring regions. His son, Samudragupta (often called Samudragupta the Great) founded a new capital city, Pataliputra, and began a conquest of the entire subcontinent. Samudragupta conquered most of India, though in the more distant regions he reinstalled local kings in exchange for their loyalty. Samudragupta was also a great patron of the arts. He was a poet and a musician, and he brought great writers, philosophers, and artists to his court. Unlike the Mauryan kings after Ashoka, who were Buddhists, Samudragupta was a devoted worshipper of the Hindu gods. Nonetheless, he did not reject Buddhism, but invited Buddhists to be part of his court and allowed the religion to spread in his realm. Chandragupta II and the Flourishing of Culture Samudragupta was briefly succeeded by his eldest son Ramagupta, whose reign was short. -

Teacher Overview: What Led to the Gupta Golden Age? How Did The

Please Read: We encourage all teachers to modify the materials to meet the needs of their students. To create a version of this document that you can edit: 1. Make sure you are signed into a Google account when you are on the resource. 2. Go to the "File" pull down menu in the upper left hand corner and select "Make a Copy." This will give you a version of the document that you own and can modify. Teacher Overview: What led to the Gupta Golden Age? How did the Gupta Golden Age impact India, other regions, and later periods in history? Unit Essential Question(s): How did classical civilizations gain, consolidate, maintain and lose their power? | Link to Unit Supporting Question(s): ● What led to the Gupta Golden Age? How did the Gupta Golden Age impact India, other regions, and later periods in history? Objective(s): ● Contextualize the Gupta Golden Age. ● Explain the impact of the Gupta Golden Age on India, other regions, and later periods in history. Go directly to student-facing materials! Alignment to State Standards 1. NYS Social Studies Framework: Key Idea Conceptual Understandings Content Specifications 9.3 CLASSICAL CIVILIZATIONS: 9.3c A period of peace, prosperity, and Students will examine the achievements EXPANSION, ACHIEVEMENT, DECLINE: cultural achievements can be designated of Greece, Gupta, Han Dynasty, Maya, Classical civilizations in Eurasia and as a Golden Age. and Rome to determine if the civilizations Mesoamerica employed a variety of experienced a Golden Age. methods to expand and maintain control over vast territories. They developed lasting cultural achievements. -

The Gupta Style of the Buddha & Its Influence in Asia

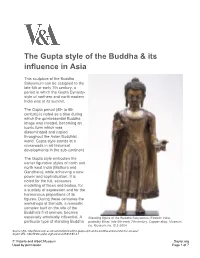

The Gupta style of the Buddha & its influence in Asia This sculpture of the Buddha Sakyamuni can be assigned to the late 6th or early 7th century, a period in which the Gupta Dynasty- style of northern and north eastern India was at its summit. The Gupta period (4th to 6th century) is noted as a time during which the quintessential Buddha image was created, becoming an iconic form which was disseminated and copied throughout the Asian Buddhist world. Gupta style stands at a crossroads in art historical developments in the sub-continent. The Gupta style embodies the earlier figurative styles of north and north west India (Mathura and Gandhara), while achieving a new power and sophistication. It is noted for the full, sensuous modelling of faces and bodies, for a subtlety of expression and for the harmonious proportions of its figures. During these centuries the workshops at Sarnath, a monastic complex built on the site of the Buddha's first sermon, became especially artistically influential. A Standing figure of the Buddha Sakyamuni, Eastern India, particular type of standing Buddha probably Bihar, late 6th-early 7th century. Copper alloy. Museum no. Museum no. IS.3-2004 Source URL: http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/t/the-gupta-style -of-the-buddha-and-its-influence-on-asia/ Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/courses/arth406/#1.4.1 © Victoria and Albert Museum Saylor.org Used by permission. Page 1 of 7 image was produced here whose body is covered by a diaphanous robe, which clings to the figure while flaring at the sides. -

The Achievements of the Gupta Empire 18.1 Introduction in Chapter 17, You Learned How India Was Unified for the First Time Under the Mauryan Empire

CHAPTER ^ An artist of the Gupta Empire painted this delicate image of the Buddha. The Achievements of the Gupta Empire 18.1 Introduction In Chapter 17, you learned how India was unified for the first time under the Mauryan Empire. In this chapter, you will explore the next great Indian empire, the Gupta Empire. The Guptas were a line of rulers who ruled much of India from 320 to 550 C.E. Many historians have called this period a golden age, a time of great prosperity and achievement. Peaceful times allow people to spend time thinking and being creative. During nonpeaceful times, people are usually too busy keeping themselves alive to spend time on inventions and artwork. For this reason, a number of advances in the arts and sciences came out during the peaceful golden age of the Gupta Empire. These achievements have left a lasting mark on the world. Archeologists have made some amazing discoveries that have helped us learn about the accom- plishments of the Gupta Empire. For example, they have unearthed palm-leaf books that were created about 550 C.E. Palm-leaf books often told religious stories. These stories are just one of many kinds of literature that Indians created under the Guptas. Literature was one of several areas of great accomplishment during India's Golden Age. In this chapter, you'll learn more about the rise of the Gupta Empire. Then Use this illustration of a palm-leaf book as a graphic you'll take a close look at seven organizer to help you learn more about Indian achieve- achievements that came out of ments during the Gupta Empire. -

The Tradition of Rama Gupta and the Indian Nationalist Historians

The Tradition of Rama Gupta and the Indian Nationalist Historians Since 1923, when a fragmentary drama called Devicandraguptam was discovered by Levy 1 and Sarasvati,2 historians have entered into violent arguments about the historicity of Rama Gupta. By doing so the historians of the present day have made the history of Rama Gupta as much a part of historiography as of ancient history. This is so for two reasons: firstly the controversy over the acceptance of the Rama Gupta story raised the problem of methods of history - how far a tradition could be used as a source. And secondly the judgements over the episode betray the attitude of certain modern historians for whom history has become as much a study of the past as the projection of the present over the past. In this paper I will try to answer two questions: how far the tradition can be trusted and why most Indian historians find it difficult to accept the historicity of the tradition. In my opinion the tradition whose story was the central theme of the drama Devicandraguptam should be treated as part of the Vikram tradition of the conquest of Ujjain by King Vikramaditya from the Sakas. As we do not know the exact date of Visakhadatta, the author of Devicandraguptam, I take the reference in Bru;a3 as the earliest reference to the story. BliD.a only tells us a part of the story, that Candra Gupta in the guise of a woman killed a Sakadhipati. From BaD-a's I Sylvain Levy, 'Deux Nouveau Traite de Dramaturgie Indiemie', Journal Asiatique, Tome CCIII, pp. -

CLASSICAL INDIA.Pdf

CLASSICAL INDIA Gupta and Mauryan empires 500 BCE-500 CE Recall: INDUS RIVER VALLEY CIVILIZATION ● What do you remember about the Indus River Valley Civilization? ● Lasted about 1000 years, from ~2500 BCE-1500 BCE The Aryans ● The Aryans, an Indo-European group, migrated into India by about 2000 BCE. ● Their sacred literature, the Vedas, are four collections of prayers, hymns, mantras, instructions for performing rituals, as well as spells and incantations. ● The Vedas are the oldest Hindu scriptures. ● Most important Veda is the Rig Veda- contains 1,028 hymns to Aryan gods. ● Passed down orally for years- not written until much later. Vedas The Aryans ● According to the Rig Veda, Ancient Indian society was divided into four groups called varnas. When the Portuguese came to India in the 1500s, they’d call these groups castes: ○ Brahmins- priests and teachers ○ Kshatriyas- warriors and rulers ○ Vaishyas- traders, farmers, and herders ○ Shudras- laborers and peasants The Aryans ● Varnas were initially flexible, then became more structured and based on birth. Later, varna would determine the kind of work people did, whom they could marry, and with whom they could eat. ● Cleanliness and purity became all-important: those considered most impure were called untouchables because of the work they did (collecting trash, cleaning toilets) ● According to a passage in the Rig Veda, the people of the four varnas were created from the body of a single being. The Caste System Aryan Kingdoms Begin ● Aryans extended their settlements east along the Ganges River ● Initially, chiefs were elected by the entire tribe. ● Around 1000 BCE, minor kings who wanted to set up territorial kingdoms arose- they struggled with one another for land and power. -

Cultural History of Indian Subcontinent; with Special Reference to Arts and Music

1 Cultural History of Indian subcontinent; with special reference to Arts and Music Author Raazia Hassan Naqvi Lecturer Department of Social Work (DSW) University of the Punjab, www.pu.edu.pk Lahore, Pakistan. Co-Author Muhammad Ibrar Mohmand Lecturer Department of Social Work (DSW) Institute of Social Work, Sociology and Gender Studies (ISSG) University of Peshawar, www.upesh.edu.pk Peshawar, Pakistan. 2 Introduction Before partition in 1947, the Indian subcontinent includes Pakistan, India and Bangladesh; today, the three independent countries and nations. This Indian Subcontinent has a history of some five millennium years and was spread over the area of one and a half millions of square miles (Swarup, 1968). The region is rich in natural as well as physical beauty. It has mountains, plains, forests, deserts, lakes, hills, and rivers with different climate and seasons throughout the year. This natural beauty has deep influence on the culture and life style of the people of the region. This land has been an object of invasion either from the route of mountains or the sea, bringing with it the new masses and ideas and assimilating and changing the culture of the people. The invaders were the Aryans, the Dravidians, the Parthians, the Greeks, the Sakas, the Kushans, the Huns, the Turks, the Afghans, and the Mongols (Singh, 2008) who all brought their unique cultures with them and the amalgamation gave rise to a new Indian Cilvilization. Indus Valley Civilization or Pre-Vedic Period The history of Indian subcontinent starts with the Indus Valley Civilization and the coming of Aryans both are known as Pre-Vedic and Vedic periods. -

May Mean Abundant Or Great

IN THE GUPTA INSCRIPTIONS 25 89 and predecessor of Narasirhhagupta is spelt as Purugupta. The reading Purugupta is unmistakeable on the fragmentary Nalanda Seal of Narasirhhagupta and is also fairly clear on the seals of Kumaragupta II. The medial u sign in the first letter of the name Purugupta is indicated by an additional stroke attached to the base of the letter and the downward elongation of its right limb; mere elongation of the right limb by itself would have denoted the short medial u as in puttras in LL. 2 and 3. In the second letter of the name, viz. ru. the medial u is shown by a small hook turned to left and joined to the foot of r. Palaeographical considerations apart, the name Purz/gupta yields a more plausible-sense than Purugupta and fits better in the series of the grand and digni- fied names of the Gupta kings. The first part of the Gupta names constituted the real or substantive name and yielded satisfactory meaning independently of the latter half, viz. gupta, which being family surname was a mere adjunct. Pura, by itself is neither a complete nor a dignified name while Puru is both. Puru or its variant Puru may, like Vainya in Vainya- gupta signify the homonymous epic hero of the lunar race who was the ancestor of the Kauravas and the Pandavas, or 90 may mean abundant or great. 10. Kumaragupta II : (No. 48, L. 5) : Kumaragupta II was the immediate successor of Purugupta in the light of the data given in two dated inscriptions, viz. -

Inscriptions, Coins and Historical Ideology

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ZENODO Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland http://journals.cambridge.org/JRA Additional services for Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Later Gupta History: Inscriptions, Coins and Historical Ideology Michael Willis Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland / Volume 15 / Issue 02 / July 2005, pp 131 150 DOI: 10.1017/S135618630500502X, Published online: 26 July 2005 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S135618630500502X How to cite this article: Michael Willis (2005). Later Gupta History: Inscriptions, Coins and Historical Ideology. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland, 15, pp 131150 doi:10.1017/ S135618630500502X Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/JRA, IP address: 131.251.133.25 on 25 Oct 2012 Later Gupta History: Inscriptions, Coins and Historical Ideology MICHAEL WILLIS In memory of Wladimir Zwalf 1932–2002 Some time before May 1886 a large metal seal was unearthed when the foundations for a house were being excavated at Bhitr¯ı, the important Gupta site near Var¯ an¯ . asi. An old and respectable family at the place (their name is not recorded in the published sources) presented the seal to C. J. Nicholls, a judge at Kanpur, who accepted it on behalf of government.1 In due course the seal was passed to the Government Museum at Lucknow. -

Indian HISTORY

Indian HISTORY AncientIndia PRE-HISTORICPERIOD G The Mesolithic people lived on hunting, fishing and food-gathering. At a later G The recent reported artefacts from stage, they also domesticated animals. Bori in Maharashtra suggest the appearance of human beings in India G The people of the Palaeolithic and around 1.4 million years ago. The early Mesolithic ages practised painting. man in India used tools of stone, G Bhimbetka in Madhya Pradesh, is a roughly dressed by crude clipping. striking site of pre-historic painting. G This period is therefore, known as the Stone Age, which has been divided into The Neolithic Age The Palaeolithic or Old Stone Age (4000-1000 BC) The Mesolithic or Middle Stone Age G The people of this age used tools and The Neolithic or New Stone Age implements of polished stone. They particularly used stone axes. The Palaeolithic Age G It is interesting that in Burzahom, (500000-9000 BC) domestic dogs were buried with their masters in their graves. G Palaeolithic men were hunters and food G First use of hand made pottery and gatherers. potter wheel appears during the G They had no knowledge of agriculture, Neolithic age. Neolithic men lived in fire or pottery; they used tools of caves and decorated their walls with unpolished, rough stones and lived in hunting and dancing scenes. cave rock shelters. G They are also called Quartzite men. The Chalcolithic Age G Homo Sapiens first appeared in the (4500-3500 BC) last phase of this period. The metal implements made by them G This age is divided into three phases were mostly the imitations of the stone according to the nature of the stone forms.