Strategic Access Management and Monitoring Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Faversham.Org/Walking

A Walk on the Wild Side faversham.org/walking FAVERSHAM - DAVINGTON - OARE - LUDDENHAM A Walk on the Wild Side Barkaway Butchers Take a Walk on the Wild Side and discover one of Kent’s most beautiful wildlife havens on the doorstep of the historic market town of Faversham. You’ll be bowled over by breath-taking views across farmland, sweeping pasture and glistening wetlands, and by an internationally important bird sanctuary, grazed by livestock as in days gone by. The scene is framed by the open sea and the local fishing boats that still land their catch here. Echoes of the area’s explosive and maritime history are all around you in this unexpectedly unspoilt and fertile habitat, rich with wild plants and skies that all year round brim with birds. A J Barkaway Butchers have supplied the finest quality meat Your route starts in Faversham’s bustling Market Place – a sea of colour, lined with centuries- products to Faversham and old half-timbered shops and houses and presided over by the elegant, stilted Guildhall. On the local area for more than a Tuesdays, Fridays and Saturdays traders selling fresh fish, fruit and vegetables, flowers and century. local produce vie for attention like their predecessors down the ages, while tempting tearooms Specialists in award winning entice you to sit back and admire the scene. hand-made pies, sausages This is an intriguing town, with specialist food stores, restaurants and bars, and the pleasing and fresh meats sourced from aroma of beer brewing most days of the week at Shepherd Neame, the country’s oldest brewer. -

Dave Brown by Dave Brown, 12-May-10 01:22 AM GMT

Dave Brown by dave brown, 12-May-10 01:22 AM GMT Saturday 8th May 2010. One look out of the window told me today was not the day for butterflies or dragonflies. A phone call from a friend then had us heading to my favourite place. Good old Dungeness. Scenery not the best in the world but the wildlife exceeedingly good. Thirty minutes later we were watching a Whiskered Tern hawking insects over the New Diggings, showing from the road to Lydd. Also present were a few hundred Swifts, Swallows, House and Sand Martins, together with a few Common Terns. A quick chat with Dave Walker (very friendly Observatory Warden) and his equally friendly assistant confirmed that the recent weather there meant little or no Butterfly or moth activity. With the rain falling harder it was time to leave Dunge and head inland. The Iberian Chifchaf at Waderslade had already been present over a week so it was time to catch up with it. On arrival at the small wood of Chesnut Avenue the bird showed and sang within a few minutes of our arrival. This is still a scarce bird in Britain so where was the crowd. In 30 minutes the maximum crowd was five, and that included 3 from our family. It sang for long periods of time and only once did it mutter the usual Chifchaf call, otherwise it was Iberian Chifchaf all the way. It also look slighlty diferent in structure and colour. To my eyes the upper parts were greener, the legs were a brown colour and the tail appeared longer. -

Field Indicators of Hydric Soils

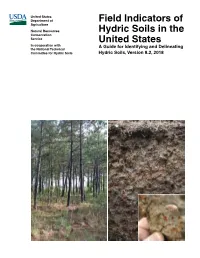

United States Department of Field Indicators of Agriculture Natural Resources Hydric Soils in the Conservation Service United States In cooperation with A Guide for Identifying and Delineating the National Technical Committee for Hydric Soils Hydric Soils, Version 8.2, 2018 Field Indicators of Hydric Soils in the United States A Guide for Identifying and Delineating Hydric Soils Version 8.2, 2018 (Including revisions to versions 8.0 and 8.1) United States Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service, in cooperation with the National Technical Committee for Hydric Soils Edited by L.M. Vasilas, Soil Scientist, NRCS, Washington, DC; G.W. Hurt, Soil Scientist, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL; and J.F. Berkowitz, Soil Scientist, USACE, Vicksburg, MS ii In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. -

Swale’S Coast

The Kent Coast Coastal Access Report This document is part of a larger document produced by Kent Area of the Ramblers’ Association and should not be read or interpreted except as part of that larger document. In particular every part of the document should be read in conjunction with the notes in the Introduction. In no circumstances may any part of this document be downloaded or distributed without all the other parts. Swale’s Coast 4.4 Swale’s Coast 4.4.1 Description 4.4.1.1 Sw ale’s coast starts at TQ828671 at Otterham Quay. It extends for 115 km to TR056650 on Graveney Marshes to the w est of The Sportsman pub. It takes in the Isle of Sheppey w hich is connected to the mainland by tw o bridges at Sw ale. It is the longest coastline in Kent. 4.4.1.2 Approximately 55 km is on PRoWs, 27 km is de facto access (though some is difficult walking) and 33 km is inaccessible to w alkers. The majority of the 27 km of inaccessible coast does not appear to be excepted land. From the Coastal Access aspect it is the most complicated coastline in Kent. Part of the mainland route is along the Saxon Shore Way. 4.4.1.3 The view to seaw ard at the start is over the Medw ay estuary. There are extensive saltings and several uninhabited islands. The route then follows the River Sw ale to Sheppey and back to the Medw ay Estuary. The north and east coasts of Sheppey look out to the Thames Estuary. -

South Fox Meadow Drainage Improvement Project

VILLAGE OF SCARSDALE WESTCHESTER COUNTY, NEW YORK COMPREHENSIVE STORM WATER MANAGEMENT SOUTH FOX MEADOW STORMWATER IMPROVEMENT PROJECT In association with WESTCHESTER COUNTY FLOOD MITIGATION PROGRAM Rob DeGiorgio, P.E., CPESC, CPSWQ The Bronx River Watershed Fox Meadow Brook Bronx River Watershed Area in Westchester 48.3 square miles (30,932 acres) 15 Sub-watersheds Percent of undeveloped land in the Watershed 3.3% (0.8 acres in Fox Meadow Brook (FMB) FMB watershed) 928 acres (5.7% of watershed) Bronx River Watershed Fox Meadow Brook George Field Park High School Duck Pond Project Philosophy and Goals •Provide flood mitigation within the Fox Meadow Brook Drainage Basin. •Reduce peak run off rates in the Bronx River Watershed through dry detention storage. •Rehabilitate and preserve natural landscapes and wetlands through invasive species management and re- construction. •Improve water quality. • Petition for and obtain County grant funding to subsidize the project. Village of Scarsdale Fox Meadow Brook Watershed SR-2 BR-4 SR-3 BR-7 BR-8 SR-5 Village of Scarsdale History •In 2009 the Village completed a Comprehensive Storm Water Management Plan. •Critical Bronx River sub drainage basin areas identified inclusive of Fox Meadow Brook (BR-4, BR-7, BR-8). •26 Capital Improvement Projects were identified, several of which comprise the Fox Meadow Detention Improvement Project. •Project included in Village’s Capital Budget. •Project has been reviewed by the NYS DEC. •NYS EFC has approved financing for the project granting Scarsdale a 50% subsidy for their local share of the costs. Village of Scarsdale Site Locations – 7 Segments 7 Project Segments 1. -

KOS News the Newsletter of the Kent Ornithological Society Number 499 March 2015

KOS News The Newsletter of the Kent Ornithological Society Number 499 March 2015 Desert Wheatear, Reculver by Matt Hindle ● Bird Sightings November 2014- February 2015 Obituary notices● Flocks● News & Announcements ● Fifty Years Ago● Letters & Notes 1 KOS Contacts – Committee Members Newsletter Editor: Norman McCanch, 23 New Street, Ash, Canterbury, Kent CT3 2BH Tel: 01304-813208 e-mail: [email protected] Membership Sec: Chris Roome, Rowland House, Station Rd., Staplehurst TN12 0PY Tel: 01580 891686 e-mail:[email protected] Chairman: Martin Coath, 14A Mount Harry Rd Sevenoaks TN13 3JH Tel: 01732-460710 e-mail: [email protected] Vice Chair.: Brendan Ryan, 18 The Crescent, Canterbury CT2 7AQ Tel: 01227 471121 e-mail: [email protected] Hon. Sec: Stephen Wood, 4 Jubilee Cottages, Throwley Forstal, Faversham ME13 0PJ. Tel: 01795 890485. e-mail: [email protected] Hon. Treasurer: Mike Henty, 12 Chichester Close, Witley, Godalming, Surrey GU8 5PA Tel: 01428-683778 e-mail: [email protected] Conservation & Surveys: : Norman McCanch, 23 New Street, Ash, Canterbury, Kent CT3 2BH Tel: 01304-813208 e-mail: [email protected] Editorial & Records: Barry Wright, 6 Hatton Close, Northfleet, DA11 8SD Tel: 01474 320918 e-mail: [email protected] Archivist: Robin Mace, 4 Dexter Close, Kennington, Ashford, TN25 4QG Tel: 01233-631509 e-mail: [email protected] Website liaison: vacant Indoor Meetings organiser: Anthea Skiffington 4 Station Approach, Bekesbourne, Kent CT4 5DT Tel: 01227 831101 e-mail: [email protected] -

WATER-QUALITY SWALES Maria Cahill, Derek C

OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY EXTENSION SERVICE Photo: Clean Water Services LOW-IMPACT DEVELOPMENT FACT SHEET WATER-QUALITY SWALES Maria Cahill, Derek C. Godwin, and Jenna H. Tilt most Oregon jurisdictions have moved away from grass. hink of a water-quality swale as a rain garden Design elements may vary in several aspects, including in motion: It treats runoff while simultaneously function, vegetation type, and physical setting. Tmoving it from one place to another. The terms “rain garden” and “swale” are often used Water-quality swales (WQ swales) are linear, vegetat- interchangeably, but rain gardens hold runoff and treat ed, channeled depressions in the landscape that convey it, while swales treat runoff as it is conveyed. Depending and treat runoff from a variety of surfaces. Runoff may on the design, the resulting water-quality benefits can be piped or channeled, or it may flow overland to a differ greatly, but water-quality swales generally provide swale. As water passes through the swale, some runoff lower benefit than rain gardens or stormwater planters. may infiltrate, or seep, into the soil. Not all swales are WQ swales. Conveyance swales, Maria Cahill, principal, Green Girl Land Development Solutions; such as ditches, move water from one place to another. Derek Godwin, watershed management faculty, professor, But these are likely narrow channels with no vegetation biological and ecological engineering, College of Agricultural Sciences, Oregon State University; Jenna H. Tilt, assistant and little to no water-quality benefits. WQ swales may be professor (senior research), College of Earth, Ocean, and planted either with grass or landscape plants, although Atmospheric Sciences, Oregon State University EM 9209 June 2018 Site conditions The channel and linear design of swales make them suitable for roadside runoff capture, although residen- tial areas with frequent, closely spaced driveway cul- verts may not be ideal locations (Barr 2001). -

Natural Vegetation of the Carolinas: Classification and Description of Plant Communities of the Lumber (Little Pee Dee) and Waccamaw Rivers

Natural vegetation of the Carolinas: Classification and Description of Plant Communities of the Lumber (Little Pee Dee) and Waccamaw Rivers A report prepared for the Ecosystem Enhancement Program, North Carolina Department of Environment and Natural Resources in partial fulfillments of contract D07042. By M. Forbes Boyle, Robert K. Peet, Thomas R. Wentworth, Michael P. Schafale, and Michael Lee Carolina Vegetation Survey Curriculum in Ecology, CB#3275 University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, NC 27599‐3275 Version 1. May 19, 2009 1 INTRODUCTION The riverine and associated vegetation of the Waccamaw, Lumber, and Little Pee Rivers of North and South Carolina are ecologically significant and floristically unique components of the southeastern Atlantic Coastal Plain. Stretching from northern Scotland County, NC to western Brunswick County, NC, the Lumber and northern Waccamaw Rivers influence a vast amount of landscape in the southeastern corner of NC. Not far south across the interstate border, the Lumber River meets the Little Pee Dee River, influencing a large portion of western Horry County and southern Marion County, SC before flowing into the Great Pee Dee River. The Waccamaw River, an oddity among Atlantic Coastal Plain rivers in that its significant flow direction is southwest rather that southeast, influences a significant portion of the eastern Horry and eastern Georgetown Counties, SC before draining into Winyah Bay along with the Great Pee Dee and several other SC blackwater rivers. The Waccamaw River originates from Lake Waccamaw in Columbus County, NC and flows ~225 km parallel to the ocean before abrubtly turning southeast in Georgetown County, SC and dumping into Winyah Bay. -

Data Collection Requirements and Procedures for Mapping Wetland, Deepwater, and Related Habitats of the United States (Version 3)

Data Collection Requirements and Procedures for Mapping Wetland, Deepwater, and Related Habitats of the United States (version 3) U.S. FISH & WILDLIFE SERVICE - ECOLOGICAL SERVICES DIVISION OF BUDGET AND TECHNICAL SUPPORT BRANCH OF GEOSPATIAL MAPPING AND TECHNICAL SUPPORT FALLS CHURCH, VA 2204 REVISED JULY 2020 1 Acknowledgements The authors would like to acknowledge the following individuals for their support and contributions: Bill Kirchner, USFWS, Region 1, Portland, OR; Elaine Blok, USFWS, Region 8, Portland, OR Brian Huberty, USFWS, Region 3, Twin Cities, MN; Ralph Tiner, USFWS, Region 5, Hadley, MA: Kevin Bon, USFWS, Region 6, Denver, CO; Jerry Tande, USFWS, Region 7, Anchorage, AK; Julie Michaelson, USFWS, Region 7, Anchorage, AK; Norm Mangrum, USFWS, St. Petersburg, FL; Dennis Fowler, USFWS, St. Petersburg, FL; Jim Terry, USFWS, St. Petersburg, FL; Martin Kodis, USFWS, Chief - Branch of Resources and Mapping Support, Washington, D.C. and David J. Stout, USFWS, Chief - Division of Habitat and Resource Conservation, Washington, D.C. Peer review was provided by the following subject matter experts: Dr. Shawna Dark and Danielle Bram, California State University - Northridge. Robb Macleod, Ducks Unlimited, Great Lakes and Atlantic Regional Office, Ann Arbor, MI; Michael Kjellson, Dept. Wildlife and Fisheries, South Dakota State University, Brookings, SD; and Deborah (Jane) Awl, Tennessee Valley Authority, Knoxville, TN. This document may be referenced as: Dahl, T.E., J. Dick, J. Swords, and B.O. Wilen. 2020. Data Collection Requirements and Procedures for Mapping Wetland, Deepwater and Related Habitats of the United States. Division of Habitat and Resource Conservation (version 3), National Wetlands Inventory, Madison, WI. 91 p. -

Oare Marshes Circular Marshes

EXPLOREKENT.ORG ENGLAND Oare Marshes COAST PATH Circular NATIONAL TRAIL WETLANDS AND WILDLIFE 5 miles (8km) Explore a tranquil nature reserve on this North Kent circular walk. Leave behind the quaint village of Oare, where boatbuilding and fishing have been a way of life for centuries. Follow the creek towards the coast to discover the wildness of the marshes. Overview Walk Description Your walk begins at The Castle Inn 1 public house, pass through a wooden kissing gate into LOCATION: Start at the footpath next to a field to the left of the creek. The footpath is The Castle Inn, Faversham ME13 0PY. marked Saxon Shore Way. Follow the path to the end of the meadow, up a couple of steps and DISTANCE: 5 miles (8km) through a gate, keeping the creek on your right. TIME: Allow 2.5 hours EXPLORER MAP: 149 Stay on this path as you walk North towards ACCESSIBILITY: No stiles, multiple gates, the coast, following the creek as it twists and narrow footbridges, a few sets of 4/5 steps. turns. Watch out for the muddy terrain if the PARKING: On the roadside in Oare. weather has been wet. Look out for a couple of REFRESHMENTS AND FACILITIES: small boats that have been shipwrecked on the The Castle and The Three Mariners public muddy shores. Pass through a kissing gate and houses in Oare, as well as The Café By The into the Oare Marshes, managed by Kent Wildlife Creek for coffees and snacks (open Wed-Sun). Trust. Continue straight and cross over a narrow footbridge. -

National Wetlands Inventory

3/23/2016 Wetlands Mapper National Wetlands Inventory Ecological Services ES Home About Us Species Wildlife and Habitat Conservation Development and Energy FWS Regions Library Newsroom NWI Menu Wetlands Mapper NWI Home The Wetlands Mapper integrates digital map data with other resource information to produce timely and relevant management and decision support tools. We recommend looking at the following prior to launching a map: Wetlands Data » Please read the Disclaimer, Data Limitations, Exclusions and Precautions, and Status and Trends » the Wetlands Geodatabase User Caution. Wetlands Layer » Refer to the following links for documentation and answers to frequently asked New: Wetland Mapping questions: Other Topics » Projects Mapper! Wetlands Mapper Documentation and Instructions Manual (PDF) Frequently Asked Questions: Wetlands Mapper (PDF) Click below to open the Mapper. National Wetlands Frequently Asked Questions web page Printing maps with the Wetlands Inventory Mapper (PDF) Mapper Introduction Contact Information » VIDEO: How to find and use the U.S Fish and Wildlife Service's Wetlands Mapper Help and Contacts Click Here to Open the Wetlands Mapper* (data last modified on October 1, 2015; best viewed by maximizing your browser window) To beta test our new HTML5 (nonFlash) mapper on your desktop, click here (FAQs). Frequently Asked Please note: Questions When in the wetlands mapper, you can change major geographic regions by using the "Zoom to: select" pull down menu located at the upper right side corner. For help with the new mobile mapper location function, please read this FAQ. Adobe Flash™ is required to access the Wetlands Mapper. Please visit the Adobe Flash Player website (http://www.adobe.com/products/flashplayer/) to download the latest version of the player. -

Destin Harbor, Joe's Bayou, and Indian Bayou Water Quality

FLORIDA RECIPIENT City of Destin, Florida Destin Harbor, Joe’s Bayou, and Indian AMOUNT $3,593,600 Bayou Water Quality Improvement LEVERAGE This project includes six projects in three focal areas included in the City of Destin’s $50,000 Master Stormwater Management plan to improve surface water quality in Destin LOCATION Harbor, Joe’s Bayou, and Indian Bayou that directly feed into the southwestern Okaloosa County, Florida portion of Choctawhatchee Bay. As part of the project, the City of Destin will establish roadside swale systems to provide treatment for shallow aquifer recharge ANNOUNCEMENT DATE November 2014 prior to discharge, construct exfiltration systems to provide stormwater treatment, and repair poorly performing culverts. Choctawhatchee Bay is a 27-mile-long estuary that PROGRESS UPDATE supports diverse aquatic and wetland habitats. No new or significant work to report. (April 2015) Submerged Aquatic Vegetation (SAV) habitat decline is a significant limiting factor for the overall productivity of the Choctawhatchee Bay, and efforts to improve water quality through the reduction of sediment input into the bay is anticipated to improve the viability of SAV in the western portions of the bay. Seagrass beds in Choctawhatchee Bay support diverse populations of fish and invertebrates, including many recreational and commercial species such as shrimp, eastern oysters, spotted seatrout, gulf menhaden, red drum, blue crab, gulf flounder and mullet. This work is complementary to additional stormwater treatment projects being supported through other oil spill settlement funds. The Gulf Environmental Benefit This suite of Fund, administered by the projects will National Fish and Wildlife complete the Foundation (NFWF), supports actions identified projects to remedy harm and in the City of eliminate or reduce the risk of Destin’s Master harm to Gulf Coast natural Stormwater resources affected by the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill.