Introduction THAILAND

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Malaysia 2019 Human Rights Report

MALAYSIA 2019 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Malaysia is a federal constitutional monarchy. It has a parliamentary system of government selected through regular, multiparty elections and is headed by a prime minister. The king is the head of state, serves a largely ceremonial role, and has a five-year term. Sultan Muhammad V resigned as king on January 6 after serving two years; Sultan Abdullah succeeded him that month. The kingship rotates among the sultans of the nine states with hereditary rulers. In 2018 parliamentary elections, the opposition Pakatan Harapan coalition defeated the ruling Barisan Nasional coalition, resulting in the first transfer of power between coalitions since independence in 1957. Before and during the campaign, then opposition politicians and civil society organizations alleged electoral irregularities and systemic disadvantages for opposition groups due to lack of media access and malapportioned districts favoring the then ruling coalition. The Royal Malaysian Police maintain internal security and report to the Ministry of Home Affairs. State-level Islamic religious enforcement officers have authority to enforce some criminal aspects of sharia. Civilian authorities at times did not maintain effective control over security forces. Significant human rights issues included: reports of unlawful or arbitrary killings by the government or its agents; reports of torture; arbitrary detention; harsh and life-threatening prison conditions; arbitrary or unlawful interference with privacy; reports of problems with -

Malaysia, September 2006

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Malaysia, September 2006 COUNTRY PROFILE: MALAYSIA September 2006 COUNTRY Formal Name: Malaysia. Short Form: Malaysia. Term for Citizen(s): Malaysian(s). Capital: Since 1999 Putrajaya (25 kilometers south of Kuala Lumpur) Click to Enlarge Image has been the administrative capital and seat of government. Parliament still meets in Kuala Lumpur, but most ministries are located in Putrajaya. Major Cities: Kuala Lumpur is the only city with a population greater than 1 million persons (1,305,792 according to the most recent census in 2000). Other major cities include Johor Bahru (642,944), Ipoh (536,832), and Klang (626,699). Independence: Peninsular Malaysia attained independence as the Federation of Malaya on August 31, 1957. Later, two states on the island of Borneo—Sabah and Sarawak—joined the federation to form Malaysia on September 16, 1963. Public Holidays: Many public holidays are observed only in particular states, and the dates of Hindu and Islamic holidays vary because they are based on lunar calendars. The following holidays are observed nationwide: Hari Raya Haji (Feast of the Sacrifice, movable date); Chinese New Year (movable set of three days in January and February); Muharram (Islamic New Year, movable date); Mouloud (Prophet Muhammad’s Birthday, movable date); Labour Day (May 1); Vesak Day (movable date in May); Official Birthday of His Majesty the Yang di-Pertuan Agong (June 5); National Day (August 31); Deepavali (Diwali, movable set of five days in October and November); Hari Raya Puasa (end of Ramadan, movable date); and Christmas Day (December 25). Flag: Fourteen alternating red and white horizontal stripes of equal width, representing equal membership in the Federation of Malaysia, which is composed of 13 states and the federal government. -

Pdf | 424.67 Kb

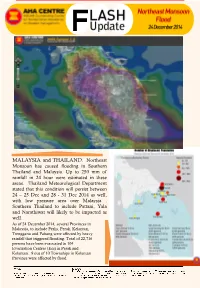

F MALAYSIA and THAILAND. Northeast THAILAND INDONESIA LAO PDR Monsoon has caused flooding in Southern Flood (Ongoing since 16-09-13) Flood Storm (Ongoing since 18-09-13) Thailand and Malaysia. Up to 250 mm of http://adinet.ahacentre.org/report/view/426 http://adinet.ahacentre.org/report/view/437 http://adinet.ahacentre.org/report/view/428 rainfall in 24 hour were estimated in these Heavy rains caused flooding in Central and Due to the heavy rainfall, flood occurred in Sigi, Tropical Depression from South Cina Sea Northern part of Thailand claiming for 31 death. Central Sulawesi Province. This incident causing flood in Champasack, Saravanne, areas. Thailand Meteorological Department More than 3 million families have been affected affected 400 people and damaged 50 houses. Savannakhet, Sekong and Attapeu, impacting with more than 1,000 houses were damaged. 200,000 people and causing 4 deaths and stated that this condition will persist between Twister damaging 1,400 houses. 24 – 25 Dec and 28 - 31 Dec 2014 as well, http://adinet.ahacentre.org/report/view/438 CAMBODIA Flood (Ongoing since 24-09-13) VIET NAM with low pressure area over Malaysia . Twister occurred in Binjai, North Sumatra Storm http://adinet.ahacentre.org/report/view/434 Province. The wind damaged 328 houses and 2 http://adinet.ahacentre.org/report/view/436 Southern Thailand to include Pattani, Yala office buildings. The monsoon and storm have triggered flooding Tropical Storm Wutip has generated flood, and Narathiwat will likely to be impacted as in 68 districts. As reported, 39 people died and landslide and strong wind in 10 provinces. -

Chapter 2 Political Development and Demographic Features

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/36062 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation Author: Xiaodong Xu Title: Genesis of a growth triangle in Southeast Asia : a study of economic connections between Singapore, Johor and the Riau Islands, 1870s – 1970s Issue Date: 2015-11-04 Chapter 2 Political Development and Demographic Features A unique feature distinguishing this region from other places in the world is the dynamic socio-political relationship between different ethnic groups rooted in colonial times. Since then, both conflict and compromise have occurred among the Europeans, Malays and Chinese, as well as other regional minorities, resulting in two regional dichotomies: (1) socially, the indigenous (Malays) vs. the outsiders (Europeans, Chinese, etc.); (2) politically, the rulers (Europeans and Malay nobles) vs. those ruled (Malays, Chinese). These features have a direct impact on economic development. A retrospective survey of regional political development and demographic features are therefore needed to provide a context for the later analysis of economic development. 1. Political development The formation of Singapore, Johor and the Riau Islands was far from a sudden event, but a long process starting with the decline of the Johor-Riau Sultanate in the late eighteenth century. In order to reveal the coherency of regional political transformations, the point of departure of this political survey begins much earlier than the researched period here. Political Development and Demographic Features 23 The beginning of Western penetration (pre-1824) Apart from their geographical proximity, Singapore, Johor and the Riau Islands had also formed a natural and inseparable part of various early unified kingdoms in Southeast Asia. -

JOHOR Linked to Singapore at the Tip of the Asian Continent, Johor Is The

© Lonely Planet 255 Johor Linked to Singapore at the tip of the Asian continent, Johor is the southern gateway to Malaysia. While it’s the most populous state in the country, tourism has taken a back seat to economic development (see the boxed text, p257 ) leaving the state with some great off-the-beaten-path destinations for those who are up to the challenge. Some of Malaysia’s most beautiful islands, within the Seribuat Archipelago, lie off the state’s east coast. They attract their fair share of Singaporean weekenders, but remain near empty during the week. Many of these islands are prime dive territory, with similar corals and fish that you’ll find at popular Tioman Island ( p274 ) but with fewer crowds. These islands are also blessed with some of the finest white-sand beaches in the country, which fringe flashy turquoise waters and wild jungles. For more adventure head to Endau-Rompin National Park or climb the eponymous peak at Gunung Ledang National Park. These jungles offer the same rich flora, (very elusive) fauna and swashbuckling action that visitors flock to experience at Taman Negara in Pahang, but JOHOR JOHOR once again crowds are rare. Anywhere you go to in the state beyond the capital will involve some determination: either by chartering a boat or joining a tour. The effort, however, is well rewarded. HIGHLIGHTS Swimming, diving and beach bumming it to the max in the Seribuat Archipelago ( p266 ) Seribuat Archipelago Discovering the surprisingly charming waterfront and colonial backstreets of Johor Endau-Rompin Bahru -

Tareqat Alawiyah As an Islamic Ritual Within Hadhrami's Arab in Johor

Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research 14 (12): 1708-1715, 2013 ISSN 1990-9233 © IDOSI Publications, 2013 DOI: 10.5829/idosi.mejsr.2013.14.12.3564 Tareqat Alawiyah as an Islamic Ritual Within Hadhrami’s Arab in Johor Nurulwahidah Fauzi, Tarek Ladjal, Tatiana A. Denisova, Mohd Roslan Mohd Nor and Aizan Ali Mat Zin Department of Islamic History and Civilization, Academy of Islamic Studies, University Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia INTRODUCTION Abdul Majid was furthermore a descendant of Sayid Idrus and was appointed as the Prime Minister of the Sultanate The state of Johor Darul Takzim is deemed to be one of Johor Lama from 1688-1697 [5]. Other official data of the most unique states in Malaysia. The uniqueness of regarding the population of Arab communities; especially the state is reflected in its historical roots where the state with regards to the Hadrami Arabs cannot be accurately was ruled across two different eras of the Sultanate. In the determined as Johor was under the control of the first era first era, the state was controlled under the Sultanate of of Sultanate with exception to a few historical chronicles Johor-Riau (1511-1685) which is also known as Johor as mentioned above. The reason for this is mainly Lama [1-3] where the administrative centre was located at because during such a time Johor was still passing Tanjung Batu. The second era shows the birth of the through a demanding stage requiring it to defend its Modern Johor Sultanate known as Johor Baru from 1686 freedom from threats stemming from the Portuguese and until today. -

Khazanah's Portfolio Value Jumps 24

MEDIA STATEMENT Kuala Lumpur, 17 January 2013 NINTH KHAZANAH ANNUAL REVIEW (“KAR 2013”) Khazanah’s portfolio value jumps 24% in 2012 to a record high Portfolio value posts record RM86.9bn Net Worth Adjusted, driven by IPOs Successful delivery of strategic and catalytic projects especially in Iskandar Malaysia • Record portfolio financial performance: o Portfolio scaled new record highs with Realisable Asset Value (“RAV”) at RM121.6 billion and Net Worth Adjusted (“NWA”) posting RM86.9 billion, as at 31st December 2012. o Growth in NWA year on year of 24.3% outstrips KLCI total return of 14.1%, driven by major IPOs. o Unaudited results of Profit Before Tax (“PBT”) of RM2.1 billion, with dividend RM1.0 billion declared. o Key prudential ratios and balance sheet indicators strengthened further. • Successful execution of strategic projects coupled with key defining transactions and developments to further catalyse growth and create value: o Particularly strong delivery in Iskandar Malaysia, as scheduled, for the 2012 “banner year”. In other catalytic projects, three theme parks successfully opened in 2012. o Defining transactions include IHH and Astro IPOs; completion of major transactions – delisting of PLUS, divestment of Proton, reversal of MAS-Air Asia share swap and UEM Group’s successful USD5.7 billion Turkish highway bid. o GLC Transformation Programme continues its solid progress; over the eight and half years since it started, G-201 and K-72 recorded Total Shareholders’ Return (“TSR”) of 14.2% and 14.4% per annum respectively, outperforming KLCI’s 13.6% per annum. Khazanah Nasional Berhad (“Khazanah”) today reported good progress on both its financial and strategic performance for 2012 at the Ninth Khazanah Annual Review (“KAR 2013”). -

A Way to Create Value Muar, Johor

INTERNATIONAL ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY MALAYSIA KULLIYAH OF LANGUAGES AND MANAGEMENT REPORT OF TOURISM PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT: A WAY TO CREATE VALUE 2019 MUAR, JOHOR PREPARED FOR: DR NUR HIDAYAH BINTI ABD RAHMAN PREPARED BY: Khairunnisa binti Mohd Rosdan 1710922 Fatin Nurul Atikah Bt Husni 151 2762 Nur Faezah binti Mohd Paruddin 171 9350 Farah Najwa binti Sarifuddin 171 3116 Nurul Fatiha binti Amran 171 0176 Nordanish Sofea Illyana Binti Roslim 171 0552 CREATING THE VALUES OF A DESTINATION THROUGH TOURISM PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT: MUAR, JOHOR Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 2 2.0 Policy Review ................................................................................................................. 3 2.1 Tourism Development Policies ........................................................................................ 3 3.0 Literature Review Food Tourism ..................................................................................... 6 4.0 Tourism Product Creation ............................................................................................... 8 4.1 Portfolio Strategy ............................................................................................................ 8 4.2 Creation Of Tourism Products ......................................................................................... 9 5.0 Methodology ................................................................................................................ -

Iskandar-Puteri.Pdf

EXCLUSIVE REPORT ISKANDAR PUTERI MALAYSIA’S PERSPECTIVE OF THE FUTURE SMART CITY As a greenfield development, Iskandar Puteri, previously known as Nusajaya, has gone through two growth phases - infrastructure and property development. Iskandar Puteri is projected to be a unique melting pot of business and culture for Iskandar Malaysia. Being one of the largest property developments in South East Asia, it aims to create synergies between Malaysian and Singaporean economies. In this issue, Property Hunter highlights the transformation of Iskandar Puteri from its palm oil plantation days to its economically vibrant city today. By Property Hunter Johor Premium Outlet www.PropertyHunter.com.my 1 EXCLUSIVE REPORT Pinewood Iskandar Malaysia SiLC (Southern Industrial and and spacious luxury resort homes THE BRIDGING OF OPPORTUNITIES Studios Logistics Clusters) nestled within 7 parks featuring 31 Located on a 49 acres site, Pinewood SiLC is Iskandar Puteri’s premier hidden, intimate and lush gardens. ISKANDAR PUTERI Iskandar Malaysia Studios is a studio industrial and environmentally Covering 275 acres, the lake, forest, complex which targets the Asia-Pacific sustainable development. Spanning wetland and canal themes are Iskandar Puteri, a newly developed planned city in Johor Bahru District, has never been intended to attract region. The state-of-the-art facilities across 1,300 acres of neighbouring combined together with tropical the agriculture or manufacturing industries. Thought to be a signature and catalytic development billed as in the studio include 100,000sqft of development-ready land, SiLC landscaping, celebrating the beauty The World in One City, its convenience to Singapore and lower cost base makes it a primary location for film stages, ranging from 15,000sqft features advanced, innovation-driven of nature. -

THE POLITICISATION of ISLAM in MALAYSIA and ITS OPPONENTS Alexander Wain*

THE POLITICISATION OF ISLAM IN MALAYSIA AND ITS OPPONENTS Alexander Wain* Abstract: This article profiles four prominent detractors of Islam’s politicisation in contemporary Malaysia. While much ink has been spilt profiling the promulgators of politicised Islam, whether in Malaysia or elsewhere, comparatively little has been written about those who oppose it. This article is a modest attempt to rectify that deficiency. It begins, however, with a brief history of that politicisation process as it has occurred in Malaysia, with particular reference to Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS) and Angkatan Belia Islam Malaysia (ABIM). This brief overview traces Malaysia’s unique form of politicised Islam to late twentieth-century intercommunal tensions driven by Malay poverty and cultural anxiety. These enabled long-standing ethno-religious associations to facilitate a blending of Islamist ideology with issues surrounding Malay rights. It is within this context that we then examine the social and educational backgrounds, principal publications, records of activism, and ideological positions of four prominent critics of Malaysian Islam’s politicisation, namely: Chandra Muzaffar, Zainah Anwar, Marina Mahathir, and Siti Kasim. The article concludes that all four figures differ from their counterparts in PAS and ABIM by possessing Western-orientated backgrounds, a long-standing dedication to multiculturalism, and a desire to orientate their work around human rights- based issues. The article concludes by suggesting how (or if) these detractors can impact the future direction of Malaysian politics. Keywords: Islam, Malaysian politics, PAS, ABIM, Chandra Muzaffar, Zainah Anwar, Marina Mahathir, Siti Kasim Introduction This article presents short contextualised biographies of four prominent opponents of Islam’s politicisation in contemporary Malaysia. -

THE POLITICISATION of ISLAM in MALAYSIA and ITS OPPONENTS Alexander Wain*

THE POLITICISATION OF ISLAM IN MALAYSIA AND ITS OPPONENTS Alexander Wain* Abstract: This article profiles four prominent detractors of Islam’s politicisation in contemporary Malaysia. While much ink has been spilt profiling the promulgators of politicised Islam, whether in Malaysia or elsewhere, comparatively little has been written about those who oppose it. This article is a modest attempt to rectify that deficiency. It begins, however, with a brief history of that politicisation process as it has occurred in Malaysia, with particular reference to Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS) and Angkatan Belia Islam Malaysia (ABIM). This brief overview traces Malaysia’s unique form of politicised Islam to late twentieth-century intercommunal tensions driven by Malay poverty and cultural anxiety. These enabled long-standing ethno-religious associations to facilitate a blending of Islamist ideology with issues surrounding Malay rights. It is within this context that we then examine the social and educational backgrounds, principal publications, records of activism, and ideological positions of four prominent critics of Malaysian Islam’s politicisation, namely: Chandra Muzaffar, Zainah Anwar, Marina Mahathir, and Siti Kasim. The article concludes that all four figures differ from their counterparts in PAS and ABIM by possessing Western-orientated backgrounds, a long-standing dedication to multiculturalism, and a desire to orientate their work around human rights- based issues. The article concludes by suggesting how (or if) these detractors can impact the future direction of Malaysian politics. Keywords: Islam, Malaysian politics, PAS, ABIM, Chandra Muzaffar, Zainah Anwar, Marina Mahathir, Siti Kasim Introduction This article presents short contextualised biographies of four prominent opponents of Islam’s politicisation in contemporary Malaysia. -

Sexuality, Islam and Politics in Malaysia: a Study of the Shifting Strategies of Regulation

SEXUALITY, ISLAM AND POLITICS IN MALAYSIA: A STUDY OF THE SHIFTING STRATEGIES OF REGULATION TAN BENG HUI B. Ec. (Soc. Sciences) (Hons.), University of Sydney, Australia M.A. in Women and Development, Institute of Social Studies, The Netherlands A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2012 ii Acknowledgements The completion of this dissertation was made possible with the guidance, encouragement and assistance of many people. I would first like to thank all those whom I am unable to name here, most especially those who consented to being interviewed for this research, and those who helped point me to relevant resources and information. I have also benefited from being part of a network of civil society groups that have enriched my understanding of the issues dealt with in this study. Three in particular need mentioning: Sisters in Islam, the Coalition for Sexual and Bodily Rights in Muslim Societies (CSBR), and the Kartini Network for Women’s and Gender Studies in Asia (Kartini Asia Network). I am grateful as well to my colleagues and teachers at the Department of Southeast Asian Studies – most of all my committee comprising Goh Beng Lan, Maznah Mohamad and Irving Chan Johnson – for generously sharing their intellectual insights and helping me sharpen mine. As well, I benefited tremendously from a pool of friends and family who entertained my many questions as I tried to make sense of my research findings. My deepest appreciation goes to Cecilia Ng, Chee Heng Leng, Chin Oy Sim, Diana Wong, Jason Tan, Jeff Tan, Julian C.H.