Allan Cunningham's Anecdotes of British Sculptors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classical Nakedness in British Sculpture and Historical Painting 1798-1840 Cora Hatshepsut Gilroy-Ware Ph.D Univ

MARMOREALITIES: CLASSICAL NAKEDNESS IN BRITISH SCULPTURE AND HISTORICAL PAINTING 1798-1840 CORA HATSHEPSUT GILROY-WARE PH.D UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART SEPTEMBER 2013 ABSTRACT Exploring the fortunes of naked Graeco-Roman corporealities in British art achieved between 1798 and 1840, this study looks at the ideal body’s evolution from a site of ideological significance to a form designed consciously to evade political meaning. While the ways in which the incorporation of antiquity into the French Revolutionary project forged a new kind of investment in the classical world have been well-documented, the drastic effects of the Revolution in terms of this particular cultural formation have remained largely unexamined in the context of British sculpture and historical painting. By 1820, a reaction against ideal forms and their ubiquitous presence during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wartime becomes commonplace in British cultural criticism. Taking shape in a series of chronological case-studies each centring on some of the nation’s most conspicuous artists during the period, this thesis navigates the causes and effects of this backlash, beginning with a state-funded marble monument to a fallen naval captain produced in 1798-1803 by the actively radical sculptor Thomas Banks. The next four chapters focus on distinct manifestations of classical nakedness by Benjamin West, Benjamin Robert Haydon, Thomas Stothard together with Richard Westall, and Henry Howard together with John Gibson and Richard James Wyatt, mapping what I identify as -

Deification in the Early Century

chapter 1 Deification in the early century ‘Interesting, dignified, and impressive’1 Public monuments were scarce in Ireland at the begin- in 7 at the expense of Dublin Corporation, was ning of the nineteenth century and were largely con- carefully positioned on a high pedestal facing the seat fined to Dublin, which boasted several monumental of power in Dublin Castle, and in close proximity, but statues of English rulers, modelled in a weighty and with its back to the seat of learning in Trinity College. pompous late Baroque style. Cork had an equestrian A second equestrian statue, a portrait of George I by statue of George II, by John van Nost, the younger (fig. John van Nost, the elder (d.), was originally placed ), positioned originally on Tuckey’s Bridge and subse- on Essex Bridge (now Capel Street Bridge) in . It quently moved to the South Mall in .2 Somewhat was removed in , and was re-erected at the end of more unusually, Birr, in County Offaly, featured a sig- the century, in ,8 in the gardens of the Mansion nificant commemoration of Prince William Augustus, House, facing out over railings towards Dawson Street. Duke of Cumberland (–) (fig. ). Otherwise The pedestal carried the inscription: ‘Be it remembered known as the Butcher of Culloden,3 he was com- that, at the time when rebellion and disloyalty were the memorated by a portrait statue surmounting a Doric characteristics of the day, the loyal Corporation of the column, erected in Emmet Square (formerly Cumber- City of Dublin re-elevated this statue of the illustrious land Square) in .4 The statue was the work of House of Hanover’.9 A third equestrian statue, com- English sculptors Henry Cheere (–) and his memorating George II, executed by the younger John brother John (d.). -

Oxford Book Fair List 2014

BERNARD QUARITCH LTD OXFORD BOOK FAIR LIST including NEW ACQUISITIONS ● APRIL 2014 Main Hall, Oxford Brookes University (Headington Hill Campus) Gipsy Lane, Oxford OX3 0BP Stand 87 Saturday 26th April 12 noon – 6pm - & - Sunday 27th April 10am – 4pm A MEMOIR OF JOHN ADAM, PRESENTED TO THE FORMER PRIME MINISTER LORD GRENVILLE BY WILLIAM ADAM 1. [ADAM, William (editor).] Description and Representation of the Mural Monument, Erected in the Cathedral of Calcutta, by General Subscription, to the Memory of John Adam, Designed and Executed by Richard Westmacott, R.A. [?Edinburgh, ?William Adam, circa 1830]. 4to (262 x 203mm), pp. [4 (blank ll.)], [1]-2 (‘Address of the British Inhabitants of Calcutta, to John Adam, on his Embarking for England in March 1825’), [2 (contents, verso blank)], [2 (blank l.)], [2 (title, verso blank)], [1]-2 (‘Description of the Monument’), [2 (‘Inscription on the Base of the Tomb’, verso blank)], [2 (‘Translation of Claudian’)], [1 (‘Extract of a Letter from … Reginald Heber … to … Charles Williams Wynn’)], [2 (‘Extract from a Sermon of Bishop Heber, Preached at Calcutta on Christmas Day, 1825’)], [1 (blank)]; mounted engraved plate on india by J. Horsburgh after Westmacott, retaining tissue guard; some light spotting, a little heavier on plate; contemporary straight-grained [?Scottish] black morocco [?for Adam for presentation], endpapers watermarked 1829, boards with broad borders of palmette and flower-and-thistle rolls, upper board lettered in blind ‘Monument to John Adam Erected at Calcutta 1827’, turn-ins roll-tooled in blind, mustard-yellow endpapers, all edges gilt; slightly rubbed and scuffed, otherwise very good; provenance: William Wyndham Grenville, Baron Grenville, 3 March 1830 (1759-1834, autograph presentation inscription from William Adam on preliminary blank and tipped-in autograph letter signed from Adam to Grenville, Edinburgh, 6 March 1830, 3pp on a bifolium, addressed on final page). -

Garofalo Book

Chapter 1 Introduction Fantasies of National Virility and William Wordsworth’s Poet Leader Violent Warriors and Benevolent Leaders: Masculinity in the Early Nineteenth-Century n 1822 British women committed a public act against propriety. They I commissioned a statue in honor of Lord Wellington, whose prowess was represented by Achilles, shield held aloft, nude in full muscular glory. Known as the “Ladies’ ‘Fancy Man,’” however, the statue shocked men on the statue committee who demanded a fig leaf to protect the public’s out- raged sensibilities.1 Linda Colley points to this comical moment in postwar British history as a sign of “the often blatantly sexual fantasies that gathered around warriors such as Nelson and Wellington.”2 However, the statue in its imitation of a classical aesthetic necessarily recalled not only the thrilling glory of Great Britain’s military might, but also the appeal of the defeated but still fascinating Napoleon. After all, the classical aesthetic was central to the public representation of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic regimes. If a classical statue was supposed to apotheosize Wellington, it also inevitably spoke to a revolutionary and mar- tial manhood associated with the recently defeated enemy. Napoleon him- self had commissioned a nude classical statue from Canova that Marie Busco speculates “would have been known” to Sir Richard Westmacott, who cast the bronze Achilles. In fact Canova’s Napoleon was conveniently located in the stairwell of Apsley House after Louis XVIII presented it to the Duke of Wellington.3 These associations with Napoleon might simply have underscored the British superiority the Wellington statue suggested. -

John Gibson and the Anglo-Italian Sculpture Market in Rome

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Loughborough University Institutional Repository John Gibson and the Anglo-Italian Sculpture Market in Rome: Letters, Sketches and Marble Alison Yarrington Tate Papers no.29 John Gibson established a hugely successful sculpture studio in Rome, and despite strong reasons to return to London, such as the cholera outbreaks in Rome in the 1830s, he remained steadfast in his allegiance to the city. His status and success in this intensely competitive environment was promoted through a sympathetic engagement with a wide variety of friends, fellow sculptors and patrons. This paper explores this method of engagement, notably through Gibson’s works for and correspondence with the 6th Duke of Devonshire. There is no place in Europe like Rome for the number of artists of different nations, there is no place where there is so much ambition of who shall produce the finest works – this concentration for fame keeps up the art and good taste. Here art is not a money making trade. You should make an effort to come here and we would go to the Vatican together.1 When John Gibson penned this letter to his friend and former fellow pupil John Barber Crouchley in early May 1837, his primary place of residence and the centre of his sculptural practice was firmly established in Rome, with his career on a firm upward trajectory towards success and recognition. By contrast, Crouchley, who had been prevented by his father from travelling abroad with Gibson when he left Liverpool in 1817, saw his ambitions as a sculptor subsequently fade. -

Women Sculptors and Their Male Assistants: a Criticised but Common Practice in France in the Long Nineteenth-Century

Laurence Riviale et Jean-François Luneau (dir.) L’Invention partagée © Presses Universitaires Blaise Pascal, 2019 ISBN (papier) – 978-2-84516-847-3 ISBN (pdf) – 978-2-84516-848-0 ISBN (ePub) – 978-2-84516-849-7 Women Sculptors and their Male Assistants: a Criticised but Common Practice in France in the long Nineteenth-Century Marjan Sterckx Maître de conférences en histoire de l’art / Associate professor in art history Université de Gand / Ghent University Abstract: The creation process of sculpture always has relied on the use of assistants. However, women sculptors often have faced a double standard. Despite simply following standard sculpting practices, they have commonly been reproached for not being the true authors of their works, as sceptics could hardly believe a woman, due to her slighter physique, could be a sculptor. The multitude of references to such rumours and comments in historic and more recent publications on women sculptors shows that it has been an international and persistent phenomenon. This article takes France, and particularly Paris, as a case study, covering the (very) long nineteenth century, with the aim of examining developments across different periods. The earliest French sculptresses – some worked as ‘amateurs’ because of their high social status while others struggled to make money – were attacked for their use of assistants. The Second Empire, with its many commissions for contemporary sculptors, saw a rise in ‘professional’ women sculptors from the middle classes. It then became more acceptable for women to employ assistants and openly communicate about it. The relatively easy access to praticiens in Paris actually seems to have helped sculptresses in nurturing professional careers alongside their male colleagues, while their training opportunities were still all but equal. -

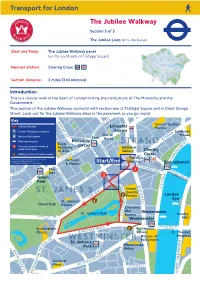

The Jubilee Walkway. Section 5 of 5

Transport for London. The Jubilee Walkway. Section 5 of 5. The Jubilee Loop (anti-clockwise). Start and finish: The Jubilee Walkway panel (on the south side of Trafalgar Square). Nearest station: Charing Cross . Section distance: 2 miles (3 kilometres). Introduction. This is a circular walk in the heart of London linking the institutions of The Monarchy and the Government. This section of the Jubilee Walkway connects with section one at Trafalgar Square and at Great George Street. Look out for the Jubilee Walkway discs in the pavement as you go round. Directions. This walk starts from Trafalgar Square. Did you know? Trafalgar Square was laid out in 1840 by Sir Charles Barry, architect of the new Houses of Parliament. The square, which is now a 'World Square', is a place for national rejoicing, celebrations and demonstrations. It is dominated by Nelson's Column with the 18-foot statue of Lord Nelson standing on top of the 171-foot column. It was erected in honour of his victory at Trafalgar. With Trafalgar Square behind you and keeping Canada House on the right, cross Cockspur Street and keep right. Go around the corner, passing the Ugandan High Commission to enter The Mall under the large stone Admiralty Arch - go through the right arch. Keep on the right-hand side of the broad avenue that is The Mall. Did you know? Admiralty Arch is the gateway between The Mall, which extends southwest, and Trafalgar Square to the northeast. The Mall was laid out as an avenue between 1660-1662 as part of Charles II's scheme for St James's Park. -

The Invisible “Sculpteuse”: Sculptures by Women in the Nineteenth-Century Urban Public Space—London, Paris, Brussels

Marjan Sterckx The Invisible “Sculpteuse”: Sculptures by Women in the Nineteenth-century Urban Public Space—London, Paris, Brussels Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 7, no. 2 (Autumn 2008) Citation: Marjan Sterckx, “The Invisible ‘Sculpteuse’: Sculptures by Women in the Nineteenth- century Urban Public Space—London, Paris, Brussels,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 7, no. 2 (Autumn 2008), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/autumn08/90-the-invisible- sculpteuse-sculptures-by-women-in-the-nineteenth-century-urban-public-spacelondon-paris- brussels. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. ©2008 Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide Sterckx: Sculptures by Women in the Nineteenth-Century Urban Public Space–London, Paris, Brussels Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 7, no. 2 (Autumn 2008) The Invisible “Sculpteuse”: Sculptures by Women in the Nineteenth-century Urban Public Space—London, Paris, Brussels[1] by Marjan Sterckx Introduction The Dictionary of Employment Open to Women, published by the London Women’s Institute in 1898, identified the kinds of commissions that women artists opting for a career as sculptor might expect. They included light fittings, forks and spoons, racing cups, presentation plates, medals and jewelry, as well as “monumental work” and the stone decoration of domestic facades, which was said to be “nice work, but poorly paid,” and “difficult to obtain without -

Anne Seymour Damer (1749-1828) Hannah Chalker

Anne Seymour Damer (1749-1828) Hannah Chalker Three Witches from Macbeth by Daniel Gardner (1775) Elizabeth Lamb, Georgiana Cavendish, Anne Damer Early Life Anne Seymour Damer was the only child of Henry Seymour Conway, a Field Marshal in the British army and Whig MP, and his wife Caroline, daughter of the fourth Duke of Argyll. Damer lived with her family in Kent at Park Place. Damer’s father’s secretary, David Hume, encouraged Damer to pursue a skill in the art of sculpture. She was exceptional at sculpting and was an honorary exhibitor at the Royal Academy. At this point in history it was rare for women to be sculptors. It is said that she was exceptionally skilled Portrait of Anne Damer at sculpting animals, according to Horace Walpole. Damer’s sculptures were of people who were fairly aristocratic, like herself. Sculptures Snuffbox given to Damer from Napoleon Princess Caroline of Elizabeth Lamb Wales Marriage Anne Seymour Conway married the Honorable John Damer on June 14, 1767. John Damer was considered a felon and a rake, but Anne’s father accepted his proposal due to Damer’s inheritance of his father’s income of 30,000 pounds a year. As it turns out Damer’s father did not make that large of an income, but rather 5,000 pounds a year. During their marriage, John Damer owed more than 70,000 pounds to various creditors, placing a strain on his and Anne’s marriage. Anne became appearing less and less with her husband, and while they never officially divorced, the couple was separated until Damer committed suicide due to his accumulating debts. -

Artful Nature

ArtfulNature 1 Artful Laura Engel andNature Amelia Rauser Produced in conjunction with the exhibition Artful Nature: Fashion and Theatricality 1770–1830, on view from February 6 to May 22, 2020, at the Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University ArtfulFashion Nature & Theatricality In a ca. 1798 French portrait in the collection of the National Gallery of Art (fig. 1), a woman poses in an austere neoclassical interior wearing the most radical version of fashionable neoclassical dress: a sheer white muslin overdress twisted at the bust and gathered with little tasseled cords to form short sleeves. An opaque, high- waisted white shift underneath the sheer muslin drapes loosely over the sitter’s lower torso and legs, while a rich red shawl fills the chair behind her and twines around her back and over her left knee. Her unpowdered hair is ornamented only with a braid; she wears no jewelry. Restrained in palette, detail, and texture, this fashionable sitter’s ensemble is arranged to emphasize that her beauty is “natural” and embodied in her physical form, rather than in artifice or ornamentation. Yet, paradoxically, it proclaims its wearer’s natural beauty using the language of art: in its color, drape, and shape, the dress construes her as a classical goddess or muse, a marble sculpture come to life. This radical fashion of undress, sometimes called empire-style or robes à la grecque, swept the metropolitan centers of Europe and 1. Circle of Jacques-Louis David. Portrait of a Young Woman in White, ca. 1798. Oil on canvas. National Gallery of Art, Chester Dale Collection, 1963.10.118 2 3 3. -

Childish Ways: Anne Damer and Other Precursors to Childe Harold's

1 CHILDISH WAYS : ANNE DAMER AND OTHER PRECURSORS TO CHILDE HAROLD ’S PILGRIMAGE JONATHAN GROSS DE PAUL UNIVERSITY How did Anne Damer and William Beckford anticipate, and in a sense make possible, Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage ? A brief overview of these Byron precursors might be helpful. In 1787, William Beckford (author of Vathek) visited Lisbon as a social outcast after his reputed affair with William Courtenay in the Powderham scandal; he struggled unsuccessfully to be admitted to the King and Queen of Portugal and kept a journal recounting the events. Four years later, in 1791, Anne Damer arrived in the same city to recover her health. Her husband had committed suicide in 1776 and she lived a precarious life as an amateur actress, sculptress, and novelist. In fact, she wrote the rough draft of Belmour (1801) during her stay. In 1808, Byron had to consider whether he would be a politician (potentially a soldier), or a writer when he came to Lisbon. Though he had written several poems, they had received mixed reviews, and it was not clear whether Byron would ever mature successfully from the poetic persona he had established in Fugitive Pieces , Hours of Idleness , and English Bards and Scotch Reviewers . When he began the poem that made him famous in Cintra at the St. Lawrence hotel, Byron’s future was not firmly established. All three figures, Beckford, Damer, and Byron, viewed Portugal and Cintra, as places to recover their lost youth, and to celebrate the creative values associated with childishness which they explored in their art, whether in Vathek , Belmour , or Childe Harold . -

David Irwin, John Flaxman 1755-1826

REVIEW David Irwin, John ilaxman 1755-1826: Sculptor, Illustrator, Designer Janice Lyle Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 15, Issue 4, Spring 1982, pp. 176-178 176 John Flaxman REVIEWS 1755-1826 Sculptor Illustrator Designer David Irwin. John Flaxman 1 755- 1826, Sculptor, Illustrator, Designer. London: Studio Vista/Christie's, 1979. New York: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., 1980. xviii + 249 pp., 282 illus. $55.00. David Irwin Reviewed by Janice Lyle ntil recently the only full-length monograph Irwin has been quite successful in the task he on John Flaxman available to scholars was set for himself. He has assembled and collated U the limited edition of W. G. Constable's information from widely diverse and often hard-to- biography published in 1927. However, 1979 saw find sources into a logical, cogent--if at times dry-' Flaxman's full re-emergence as an artistic exposition of Flaxman's development. Undoubtedly, personality. The re-evaluation of his importance the book's greatest contribution to scholarship is reached its peak with the major Flaxman exhibitions its presentation of factual information in an held in Hamburg, Copenhagen, and London accompanied organized format. by an extensive catalogue edited by David Bindman, the numerous reviews of these exhibitions, and the publication of David Irwin's monograph, John Flaxman Technically the book is excellent. It is well- 2755-2826 Soulptor Illustrator Designer. Thus, John designed and offers 282 illustrations, all black-and- Flaxman, whose art Irwin promoted as early as 1959 white (a fact which is less distressing with (see "Reviving Interest in Flaxman," Connoisseur, Flaxman's work than with that of most artists, as the 144 [1959], 104-05), is now the subject of much majority of his drawings are pen-and-ink while his modern attention.