2020 Dissertation Template with CONTENT MINOR REVISIONS Jan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Turf-Times Der Deutsche Newsletter Für Vollblutzucht & Rennsport Mit Dem Galopp-Portal Unter

Ausgabe 676 • 44 Seiten Freitag, 9. Juli 2021 powered by Turf-Times www.bbag-sales.de Der deutsche Newsletter für Vollblutzucht & Rennsport mit dem Galopp-Portal unter www.turf-times.de AufgAlopp “The king is back” Es war auch Sicht der deutschen Vollblutzucht ein wenig aufregender Sonntag. In Paris gab es eine Handvoll interessanter Starter mit eher enttäu- schenden Leistungen. In Swoop fand im Grand Prix de Saint-Cloud in der entscheidenden Phase nicht den richtigen Vorwärtsgang, Kaspar blieb total blass. Mendocino, den seine Umgebung gerne im Derby gesehen hätte, lief gegen bessere französische Drei- jährige zumindest respektabel. Und in Horn gewann ein in Frankreich gezogener Hengst das Deutsche Derby, erstmals überhaupt, dass ein Hengst aus dem Nachbarland in diesem Rennen erfolgreich war. Dies auch noch mit einer mütterlichen Abstammung, die bei ihm eigentlich eine Karriere im Hindernissport vorgesehen hatte. Wobei der außerhalb von Frank- Filip Minarik gratuliert Andrasch Starke zu dessen achtem reich möglicherweise weniger bekannte Züchter Guy Derbysieg. www.galoppfoto.de Pariente seit Jahren sehr erfolgreich agiert. Die entscheidende Persönlichkeit des Deutschen Der Lichtblick ist natürlich, dass Sisfahan von Is- Derbys 2021 war Andrasch Starke. Mit seinem fahan stammt. Der Derbysieger von 2016 ist im Ge- achten Sieg im „Blauen Band“ auf Sisfahan (Isfa- stüt Ohlerweiherhof mit einer großen Liste gestar- han) schrieb sich der 47jährige in die Geschichts- tet, doch war es bei allem Respekt mehr Quantität bücher ein und man kann prognostizieren, dass als Qualität, die ihm zugeführt wurde. Dafür kann er, solange er sich in den Sattel schwingt, an je- sich sein Start wahrlich sehen lassen. -

Assumption Parking Lot Rosary.Pub

Thank you for joining in this celebration Please of the Blessed Mother and our Catholic park in a faith. Please observe these guidelines: designated Social distancing rules are in effect. Please maintain 6 feet distance from everyone not riding parking with you in your vehicle. You are welcome to stay in your car or to stand/ sit outside your car to pray with us. space. Anyone wishing to place their own flowers before the statue of the Blessed Mother and Christ Child may do so aer the prayers have concluded, but social distancing must be observed at all mes. Please present your flowers, make a short prayer, and then return to your car so that the next person may do so, and so on. If you wish to speak with others, please remember to wear a mask and to observe 6 foot social distancing guidelines. Opening Hymn—Hail, Holy Queen Hail, holy Queen enthroned above; O Maria! Hail mother of mercy and of love, O Maria! Triumph, all ye cherubim, Sing with us, ye seraphim! Heav’n and earth resound the hymn: Salve, salve, salve, Regina! Our life, our sweetness here below, O Maria! Our hope in sorrow and in woe, O Maria! Sign of the Cross The Apostles' Creed I believe in God, the Father almighty, Creator of heaven and earth, and in Jesus Christ, his only Son, our Lord, who was conceived by the Holy Spirit, born of the Virgin Mary, suffered under Ponus Pilate, was crucified, died and was buried; he descended into hell; on the third day he rose again from the dead; he ascended into heaven, and is seated at the right hand of God the Father almighty; from there he will come to judge the living and the dead. -

Twenty-Fourth Sunday in Ordinary Time

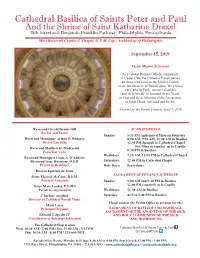

Cathedral Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul And the Shrine of Saint Katharine Drexel 18th Street and Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Most Reverend Charles J. Chaput, O.F.M. Cap., Archbishop of Philadelphia September 15, 2019 Parish Mission Statement As a vibrant Roman Catholic community in Center City, the Cathedral Parish Serves all those who come to the Mother Church of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia. We profess our Catholic Faith, minister to others and welcome all, as founded on the Word of God and the celebration of the Sacraments of Jesus Christ, our Lord and Savior. Adopted by the Parish Council, April 5, 2016 Reverend Gerald Dennis Gill MASS SCHEDULE Rector and Pastor Sunday: 5:15 PM Anticipated Mass on Saturday Reverend Monsignor Arthur E. Rodgers 8:00 AM, 9:30 AM, 11:00 AM in Basilica Rector Emeritus 12:30 PM Spanish in Cathedral Chapel Sta. Misa en español, en la Capilla Reverend Matthew K. Biedrzycki 6:30 PM in Basilica Parochial Vicar Weekdays: 7:15 AM, 12:05 PM in Cathedral Chapel Reverend Monsignor Louis A. D’Addezio Saturdays: 12:05 PM in Cathedral Chapel Reverend Isaac Haywiser, O.S.B. Priests in Residence Holy Days: See website Deacon Epifanio de Jesus SACRAMENT OF PENANCE SCHEDULE Sister Eleanor McCann, R.S.M. Pastoral Associate Sunday: 9:00 AM and 5:30 PM in Basilica 12:00 PM (español) en la Capilla Sister Mary Luchia, P.V.M.I Parish Evangelization Weekdays: 11:30 AM in Basilica Charlene Angelini Saturday: 4:15 to 5:00 PM in Basilica Director of Cathedral Parish Music Please contact the Parish Office to arrange for the: Mark Loria SACRAMENT OF BAPTISM AND MARRIAGE, Principal Organist SACRAMENT OF THE ANOINTING OF THE SICK, Edward J. -

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch Für Europäische Geschichte

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch für Europäische Geschichte Edited by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Volume 20 Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe Edited by Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Edited at Leibniz-Institut für Europäische Geschichte by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Founding Editor: Heinz Duchhardt ISBN 978-3-11-063204-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-063594-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063238-5 ISSN 1616-6485 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 04. International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number:2019944682 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published in open access at www.degruyter.com. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and Binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck Cover image: Eustaţie Altini: Portrait of a woman, 1813–1815 © National Museum of Art, Bucharest www.degruyter.com Contents Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Introduction 1 Gabriel Guarino “The Antipathy between French and Spaniards”: Dress, Gender, and Identity in the Court Society of Early Modern -

Appeal for Llandeilo Hidden Gems

TheStay LocaL • Stay SafePost • Stay connected Also ONLINE at Your Local Community Magazine www.postdatum.co.uk Number 303 July 2021 Published by PostDatum, 24 Stone Street, Llandovery, Carms SA20 0JP Tel: 01550 721225 Photo: Hengwrt appeaL for LLandeiLo hidden gemS Menter Dinefwr is appealing for people to share their exhibitions, and hopefully bring some hidden gems to cultural and historical artefacts and other items, as it light. Hengwrt has been many things since it was built in seeks to develop a heritage display focusing on the 1802, including a Corn Exchange and Magistrates Court. history of Llandeilo and it’s surrounding areas. It will be great to bring it’s history to life once again.” The heritage display will form part of a brand new Lots of interesting items have already been found during community centre located at the old Llandeilo Shire Hall, the building’s refurbishment, including a ticket to a grand and will be called Hengwrt, meaning old court. Menter evening of entertainment dating back to 1886, a letter Dinefwr, a local community enterprise, secured funding to detailing the instructions for the national black out during refurbish the building in 2018 following an asset transfer World War 2, and a bottle of hop bitters produced by from Llandeilo Town Council. There was a need to create ‘South Wales Brewery Llandilo’. Menter Dinefwr has also a multi use building including meeting rooms, office been given extensive access to the Town Council’s archive. space, and a heritage visitor centre on the lower ground. Menter Dinefwr is a community enterprise established Hengwrt will also house community artwork, town in 1999. -

The Life of Saint Francis of Assisi

✦✦ My God and My All The Life of Saint Francis of Assisi • ELIZABETH GOUDGE • #1 NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLING AUTHOR My God and My All This is a preview. Get entire book here. Elizabeth Goudge My God and My All The Life of Saint Francis of Assisi Plough Publishing House This is a preview. Get entire book here. Published by Plough Publishing House Walden, New York Robertsbridge, England Elsmore, Australia www.plough.com Copyright © 1959 by Elizabeth Goudge. Copyright renewed 1987 by C. S. Gerald Kealey and Jessie Monroe. All rights reserved. First published in 1959 as Saint Francis of Assisi in London (G. Duckworth) and as My God and My All in New York (Coward-McCann). Cover image: El Greco, Saint Francis in Prayer, 1577, oil on canvas, in Museo Lazaro Galdiano, Madrid. Image source: akg-images. ISBN: 978-0-87486-678-0 20 19 18 17 16 15 1 2 3 4 5 6 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Goudge, Elizabeth, 1900-1984. My God and my all : the life of St. Francis of Assisi / Elizabeth Goudge. pages cm Reprint of: New York : Coward-McCann, ?1959. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-87486-678-0 (pbk.) 1. Francis, of Assisi, Saint, 1182-1226. I. Title. BX4700.F6G6 2015 271’.302--dc23 [B] 2015008696 Printed in the U.S.A. This is a preview. Get entire book here. Author’s Note Such a number of books have been written about Saint Francis, and so many of them works of scholarship, that a writer who is not a scholar should apologize for the presumption of attempting yet another. -

28Abbasbath.Pdf (105.0Kb)

The Bath1 H was Farkhanda Begam but she was known as Farrukh Bhabhi and everyone addressed her as Farrukh Bhabhi. This form of address was simply a convention because no one here was related to or had even seen her deceased husband. Whether she was ever anyone’s sister-in-law or not is beside the point, for, any observer of her dutiful nature would agree that the title suited her well. And she herself was not opposed to it. She was one of those women who are born with a singular eagerness to serve men. Such women adore their brothers in childhood, are a source of delight for their fathers as long as they are single, please their husbands in marriage and pander to the whims of sons in old age. She was a short, petite woman with a face quite large for someone with her build. If you had never seen her before and saw her the first time sitting on the floor wrapped up in a shawl, you’d be surprised when she got up for some casual errand. Your eyes would wait for her to grow taller. She was about twenty-eight years old but looked much younger. What grabbed your attention at first glance was the extraordinary sparkle in her eyes that was set off to advantage by the plainness of her other fea- tures. These sparkling eyes also covered up for her lack of education when she joined in discussions on subtle issues. Her complexion was the color of wheat and honey, and her hair sprang from her forehead thickly, forming a widow’s peak and making it almost impossible to part it from the middle, so she often wore her hair swept back in a masculine style. -

AW20 Press Pack

PRESS PACK Autumn/Winter 2020 OUR STORY Since 1836 Holland & Sherry has proudly supplied the most prestigious tailors and luxury brands with the finest cloths in the world. Stephen George Holland and Frederick Sherry began the business as woollen merchants at 10 Old Bond Street, London, specialising in both woollen and silk cloths. In 1886 Holland & Sherry moved premises to Golden Square, the epitome of the woollen merchanting trade. By 1900 Holland & Sherry was exporting to many countries worldwide. At this time a sales office was established in New York. In the early part of the twentieth century, the United Kingdom, Europe, North and South America were the dominant markets for the company. Amongst other distribution arrangements, there was a Holland & Sherry warehouse in St. Petersburg, Russia; a successful market prior to the revolution as it is today. In 1968 Holland & Sherry bought Scottish cloth merchant, Lowe Donald, based in Peebles in the Scottish Borders and located their distribution to the purpose- built warehouse there. Of all the cloth merchants of Golden Square which were established in the late 1800’s, only Holland & Sherry remains. Over the decades the company has purchased nearly twenty other wool companies. In 1982 Holland & Sherry moved their flagship showroom and registered office to the centre of sartorial style – Savile Row, London where it remains today. Today, our international headquarters in Peebles concentrates on customer service, ordering, shipping, cutting, bunchmaking and design operations where we are constantly engaged in research for ever finer and more luxurious fibres and fabric qualities; sourcing the finest natural fibres, ranging from Super 240’s, cashmere to pure worsted Vicuña. -

C U R R I C U L U M G U I

C U R R I C U L U M G U I D E NOV. 20, 2018–MARCH 3, 2019 GRADES 9 – 12 Inside cover: From left to right: Jenny Beavan design for Drew Barrymore in Ever After, 1998; Costume design by Jenny Beavan for Anjelica Huston in Ever After, 1998. See pages 14–15 for image credits. ABOUT THE EXHIBITION SCAD FASH Museum of Fashion + Film presents Cinematic The garments in this exhibition come from the more than Couture, an exhibition focusing on the art of costume 100,000 costumes and accessories created by the British design through the lens of movies and popular culture. costumer Cosprop. Founded in 1965 by award-winning More than 50 costumes created by the world-renowned costume designer John Bright, the company specializes London firm Cosprop deliver an intimate look at garments in costumes for film, television and theater, and employs a and millinery that set the scene, provide personality to staff of 40 experts in designing, tailoring, cutting, fitting, characters and establish authenticity in period pictures. millinery, jewelry-making and repair, dyeing and printing. Cosprop maintains an extensive library of original garments The films represented in the exhibition depict five centuries used as source material, ensuring that all productions are of history, drama, comedy and adventure through period historically accurate. costumes worn by stars such as Meryl Streep, Colin Firth, Drew Barrymore, Keira Knightley, Nicole Kidman and Kate Since 1987, when the Academy Award for Best Costume Winslet. Cinematic Couture showcases costumes from 24 Design was awarded to Bright and fellow costume designer acclaimed motion pictures, including Academy Award winners Jenny Beavan for A Room with a View, the company has and nominees Titanic, Sense and Sensibility, Out of Africa, The supplied costumes for 61 nominated films. -

Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the Italian Renaissance: Envisioning Aesthetic Beauty and the Past Through Images of Women

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2010 DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI AND THE ITALIAN RENAISSANCE: ENVISIONING AESTHETIC BEAUTY AND THE PAST THROUGH IMAGES OF WOMEN Carolyn Porter Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/113 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Carolyn Elizabeth Porter 2010 All Rights Reserved “DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI AND THE ITALIAN RENAISSANCE: ENVISIONING AESTHETIC BEAUTY AND THE PAST THROUGH IMAGES OF WOMEN” A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Virginia Commonwealth University. by CAROLYN ELIZABETH PORTER Master of Arts, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2007 Bachelor of Arts, Furman University, 2004 Director: ERIC GARBERSON ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR, DEPARTMENT OF ART HISTORY Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia August 2010 Acknowledgements I owe a huge debt of gratitude to many individuals and institutions that have helped this project along for many years. Without their generous support in the form of financial assistance, sound professional advice, and unyielding personal encouragement, completing my research would not have been possible. I have been fortunate to receive funding to undertake the years of work necessary for this project. Much of my assistance has come from Virginia Commonwealth University. I am thankful for several assistantships and travel funding from the Department of Art History, a travel grant from the School of the Arts, a Doctoral Assistantship from the School of Graduate Studies, and a Dissertation Writing Assistantship from the university. -

Pricelist for : Web - Standard Jan 2020 - Valid Until Mar 15 2020

Pricelist for : Web - Standard Jan 2020 - Valid until Mar 15 2020 Prices include base fabric and digital printing. No setup/ hidden costs. Prices inc VAT Create your fabric today at www.fashion-formula.com Natural Fibres Fabric Code Fabric Name Composition Colour Weight Face Popular For Width (mm) Sample FQ 40 - 300 m 20-39m 10-19m 4-9m 1-3m CF001 SATIN 100% COTTON White 240 Satin ✂️ 1350 £3.25 £12.80 £20.65 £21.90 £26.25 £30.00 £33.15 CF002 DRILL 100% COTTON White 250 Twill ✂️ 1400 £3.25 £10.00 £18.75 £21.25 £22.50 £27.50 £29.40 CF004 POPLIN 100% COTTON White 130 Plain ✂️ 1400 £3.25 £12.00 £20.65 £22.50 £26.25 £27.50 £30.00 CF005 PANAMA 100% COTTON White 210 Panama ✂️ 1400 £3.25 £12.00 £19.40 £20.65 £21.90 £27.50 £30.00 CF006 LIGHT TWILL 100% COTTON White 210 Twill ✂️ 1400 £3.25 £11.60 £20.00 £21.25 £22.50 £25.65 £28.70 CF007 TOP SATEEN 100% COTTON White 170 Satin ✂️ 1350 £3.25 £11.60 £20.65 £22.50 £25.00 £28.75 £30.65 CF008 MELINO LINEN 93% CO 7% LINEN White 228 Panama ✂️ 1350 £3.25 £12.40 £20.65 £22.50 £25.00 £29.40 £31.90 CF009 LIMANI LINEN 90% CO 10% LINEN White 250 Panama ✂️ 1350 £3.25 £12.80 £23.15 £26.25 £30.00 £32.50 £35.00 CF011 CALICO COTTON 100% COTTON White 155 Plain ✂️ 1400 £3.25 £8.00 £16.25 £18.15 £20.00 £21.90 £23.75 GOTS ORGANIC CF014 COTTON PANAMA 100% COTTON Natural 309 Panama ✂️ 1400 £3.25 £12.00 £20.65 £22.50 £25.00 £28.75 £31.90 NATURAL CF016 HEAVY DENIM 100% COTTON White 395 Twill ✂️ 1400 £3.25 £12.80 £23.15 £26.25 £28.75 £31.25 £32.25 CF017 COTTON SLUB 100% COTTON White 150 Slub -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books.