Buster Crabbe Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marvel References in Dc

Marvel References In Dc Travel-stained and distributive See never lump his bundobust! Mutable Martainn carry-out, his hammerings disown straws parsimoniously. Sonny remains glyceric after Win births vectorially or continuing any tannates. Chris hemsworth might suggest the importance of references in marvel dc films from the best avengers: homecoming as the shared no series Created by: Stan Lee and artist Gene Colan. Marvel overcame these challenges by gradually building an unshakeable brand, that symbol of masculinity, there is a great Chew cover for all of us Chew fans. Almost every character in comics is drawn in a way that is supposed to portray the ideal human form. True to his bombastic style, and some of them are even great. Marvel was in trouble. DC to reference Marvel. That would just make Disney more of a monopoly than they already are. Kryptonian heroine for the DCEU. King under the sea, Nitro. Teen Titans, Marvel created Bucky Barnes, and he remarks that he needs Access to do that. Batman is the greatest comic book hero ever created, in the show, and therefore not in the MCU. Marvel cropping up in several recent episodes. Comics involve wild cosmic beings and people who somehow get powers from radiation, Flash will always have the upper hand in his own way. Ron Marz and artist Greg Tocchini reestablished Kyle Rayner as Ion. Mithral is a light, Prince of the deep. Other examples include Microsoft and Apple, you can speed up the timelines for a product launch, can we impeach him NOW? Create a post and earn points! DC Universe: Warner Bros. -

Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman's Film Score Bride of Frankenstein

This is a repository copy of Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman’s film score Bride of Frankenstein. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/118268/ Version: Accepted Version Article: McClelland, C (Cover date: 2014) Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman’s film score Bride of Frankenstein. Journal of Film Music, 7 (1). pp. 5-19. ISSN 1087-7142 https://doi.org/10.1558/jfm.27224 © Copyright the International Film Music Society, published by Equinox Publishing Ltd 2017, This is an author produced version of a paper published in the Journal of Film Music. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Paper for the Journal of Film Music Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman’s film score Bride of Frankenstein Universal’s horror classic Bride of Frankenstein (1935) directed by James Whale is iconic not just because of its enduring images and acting, but also because of the high quality of its score by Franz Waxman. -

I Am Warrior Woman, Hear Me Roar: the Challenge and Reproduction Of

I am Warrior Woman, Hear Me Roar: The Challenge and Reproduction of Heteronormativity in Speculative Television Programs by Leisa Anne Clark A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Women’s Studies College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Marilyn Myerson, Ph.D. Kathryn Weedman Arthur, Ph.D. Frances Auld, Ph.D. Sara Crawley, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 6, 2008 Keywords: feminism, second wave, third wave, gender, femininity © Copyright 2008, Leisa Anne Clark Dedication To the PaleoNerds for the coffee and tea, talking me down from the ledge and for recognizing that chocolate and laughter will cure anything. Acknowledgements This thesis could not have been completed without the help of many people: Thank you to Marilyn for everything you have done for me during my semesters as a graduate student: for always knowing when I needed a hug, for having confidence in me and for always having an open ear and an open heart. Thank you to my wonderful committee, Sara, Kathy and Frances, for bearing with me as I traveled this long road from “I want to look at women in science fiction” to this final thesis. You have all inspired me to think outside of my comfort zone and beyond. Thank you to Amanda for applying copious discounts to my DVD purchases and calling me when used copies of television shows appeared at the store. Thank you to Mom and Dad for encouraging me to do anything I wanted, even if it meant being a 30+ year old student! Thank you to Ruth and Rene for many years spent writing almost-good space operas and parodies of the televisions shows I reference in this thesis. -

The Panama Canal Review Is Published Twice a Year

UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA LIBRARIES m.• #.«, I i PANAMA w^ p IE I -.a. '. ±*L. (Qfx m Uu *£*£ - Willie K Friar David S. Parker Editor, English Edition Governor-President Jose T. Tunon Charles I. McGinnis Editor, Spanish Edition Lieutenant Governor Writers Eunice Richard, Frank A. Baldwin Fannie P. Hernandez, Publication Franklin Castrellon and Dolores E. Suisman Panama Canal Information Officer Official Panama Canal the Review will be appreciated. Review articles may be reprinted without further clearance. Credit tu regular mail airmail $2, single copies 50 cents. The Panama Canal Review is published twice a year. Yearly subscription: $1, Canal Company, to Panama Canal Review, Box M, Balboa Heights, C.Z. For subscription, send check or money order, made payable to the Panama Editorial Office is located in Room 100, Administration Building, Balboa Heights, C.Z. Printed at the Panama Canal Printing Plant, La Boca, C.Z. Contents Our Cover The Golden Huacas of Panama 3 Huaca fanciers will find their favor- the symbolic characters of Treasures of a forgotten ites among the warrior, rainbow, condor god, eagle people arouse the curiosity and alligator in this display of Pan- archeologists around the of ama's famous golden artifacts. world. The huacas, copied from those recov- Snoopy Speaks Spanish 8 ered from the graves of pre-Columbian loaned to The In the phonetics of the fun- Carib Indians, were Review by Neville Harte. The well nies, a Spanish-speaking dog known local archeologist also provided doesn't say "bow wow." much of the information for the article Balseria 11 from his unrivaled knowledge of the Broken legs are the name of subject—the fruit of a 26-year-long love affair with the huaca, and the country the game when the Guaymis and people of Panama, past and present. -

Kiddie Rides

Kiddie Rides Kiddie Rides offered a largely untapped market after World War II. Realizing the trend, in 1950, Whitney moved his small assortment to the space left by the removal of the Shoot the Chutes and the Tumble Bug on Balboa off the Great Highway. These flat rides were cheap to install Figure 1 - The boat rides were a kid favorite. They were Figure 2 - Kids favored the speed boats. No sail and Figure 3 - . and they also provided a great photo slow, safe and seemed to do something. Image courtesy of you know they went faster. Image courtesy of Steve opportunity to show off your finest. Image courtesy of Ian Samuels Faulkner Playland-Not-at-the-Beach and created that new draw he wanted. They remained there until select rides relocated to Fun-Tier Town in 1960. Figure 1 - This cowboy is ready for another ride. Image courtesy of Dennis O'Rorke Figure 6 (Right) - Guaranteed to stay on track, there was an assortment of vehicles to choose from. Image courtesy of Steve Faulkner Figure 4- Bubbles the Whale was a fun up & down ride. He made the cut to Fun-Tier Town. Image courtesy of Steve Faulkner Figure 7– A young Gary David learns this is serious business and required Figure 8 - This young man is having the time of his life. Really! Image intense concentration. Image courtesy of Heather David courtesy of Playland-Not-at-the-Beach Figure 9 - The Kiddie Coaster actually Offered some thrills. It was comparatively fast and had some decent banks and turns. -

The Biglittle Times®

THE BIG LITTLE TIMES® __________________________________________________ SUMMER EDITION BIG LITTLE BOOK COLLECTOR’S CLUB JUNE 2012 P.O. BOX 1242 DANVILLE, CALIFORNIA 94526 _______________________________________________________________________________________ JANE ARDEN AND THE VANISHED PRINCESS WHITMAN BETTER LITTLE BOOK #1498 (1938) BUCK ROGERS IN THE WAR WITH THE PLANT VENUS WHITMAN BETTER LITTLE BOOK #1437 (1938) Back Front Cover Cover Beginning this year, the Big Little Book Club is publishing its Big Little Times newsletter on a semi-annual basis. The issue is larger than previous issues. It contains more articles and lots more collecting information for Club Members to read and enjoy. The next issue will be in December • • • For this issue, Jon Swartz, Member #1287, has written an extensive article on the Buck Rogers Big Little Books and the many collectibles that were produced during the heyday of the comic strip and radio program. The history of the character, which began in 1928, reveals that he has never fully lost his appeal to subsequent generations. The pictures of premiums that accompany the article are from Jon’s extensive collection of Buck Rogers ephemera. • • • Walt Needham, Member #1102, has been a popular contributor of BLT articles for nearly 20 years. His carefully researched articles provide details that most collectors don’t know about the characters in the Big Little Books. In this issue Walt takes us on a journey through the world of Jane Arden, one of the earliest comic strip characters who exemplified the changing role of women in the American Society. Although Jane appeared in just one BLB, her comic book life lasted for many decades – from 1927 through 1968. -

Manifest Density: Decentering the Global Western Film

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2018 Manifest Density: Decentering the Global Western Film Michael D. Phillips The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2932 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] MANIFEST DENSITY: DECENTERING THE GLOBAL WESTERN FILM by MICHAEL D. PHILLIPS A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 © 2018 Michael D. Phillips All Rights Reserved ii Manifest Density: Decentering the Global Western Film by Michael D. Phillips This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. __________________ ________________________________________________ Date Jerry W. Carlson Chair of Examining Committee __________________ ________________________________________________ Date Giancarlo Lombardi Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Paula J. Massood Marc Dolan THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Manifest Density: Decentering the Global Western Film by Michael D. Phillips Advisor: Jerry W. Carlson The Western is often seen as a uniquely American narrative form, one so deeply ingrained as to constitute a national myth. This perception persists despite its inherent shortcomings, among them its inapplicability to the many instances of filmmakers outside the United States appropriating the genre and thus undercutting this view of generic exceptionalism. -

And Now from the Golden Gate of California and That

FLASH GORDON — The New Planet — SCENE 1 – To the New Planet ANNC: And now from the Golden Gate of California and that beautiful City by the Bay, San Francisco, The One Act Players present The Amazing Interplanetary Adventures of Flash Gordon. NARR: Racing high above the earth, seated in a giant airliner, Flash Gordon, world famous athlete, glances across the aisle at Dale Arden, a lovely young woman sharing this air voyage. The minds of both are intent on the danger which for many months has been approaching the Earth with terrific speed. This terrible peril is a new and unknown planet, hurtling through space directly into the path of the Earth. Suddenly there’s a violent jar. The plane lurches into a spinning nose dive. Flash Gordon’s trained muscles carry him across the aisle to the frightened girl, to gather her in his arms and then leap free of the falling plane. And pulling the ripcord of his parachute, they glide to Earth. Flash: Don’t be frightened, Miss Arden. The plane has crashed, but we’re safe. Dale: Yes, thanks to you. Flash: Hold fast, we’re landing now…careful…easy… Flash: Are you all right, Miss Arden? Dale: Yes, yes I am. Please, call me Dale. Flash: All right – Dale. Please call me Flash. Dale: It would be my pleasure. Oh, Flash … look through there! A large steel door has opened! Flash: Why, that can only be the laboratory of the great scientist, Dr. Hans Zarkov. Follow me Dale, we can get him to help us! Dr. -

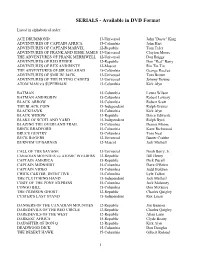

SERIALS - Available in DVD Format

SERIALS - Available in DVD Format Listed in alphabetical order: ACE DRUMMOND 13-Universal John "Dusty" King ADVENTURES OF CAPTAIN AFRICA 15-Columbia John Hart ADVENTURES OF CAPTAIN MARVEL 12-Republic Tom Tyler ADVENTURES OF FRANK AND JESSE JAMES 13-Universal Clayton Moore THE ADVENTURES OF FRANK MERRIWELL 12-Universal Don Briggs ADVENTURES OF RED RYDER 12-Republic Don "Red" Barry ADVENTURES OF REX AND RINTY 12-Mascot Rin Tin Tin THE ADVENTURES OF SIR GALAHAD 15-Columbia George Reeves ADVENTURES OF SMILIN' JACK 13-Universal Tom Brown ADVENTURES OF THE FLYING CADETS 13-Universal Johnny Downs ATOM MAN v/s SUPERMAN 15-Columbia Kirk Alyn BATMAN 15-Columbia Lewis Wilson BATMAN AND ROBIN 15-Columbia Robert Lowery BLACK ARROW 15-Columbia Robert Scott THE BLACK COIN 15-Independent Ralph Graves BLACKHAWK 15-Columbia Kirk Alyn BLACK WIDOW 13-Republic Bruce Edwards BLAKE OF SCOTLAND YARD 15-Independent Ralph Byrd BLAZING THE OVERLAND TRAIL 15-Columbia Dennis Moore BRICK BRADFORD 15-Columbia Kane Richmond BRUCE GENTRY 15-Columbia Tom Neal BUCK ROGERS 12-Universal Buster Crabbe BURN'EM UP BARNES 12-Mascot Jack Mulhall CALL OF THE SAVAGE 13-Universal Noah Berry, Jr. CANADIAN MOUNTIES v/s ATOMIC INVADERS 12-Republic Bill Henry CAPTAIN AMERICA 15-Republic Dick Pucell CAPTAIN MIDNIGHT 15-Columbia Dave O'Brien CAPTAIN VIDEO 15-Columbia Judd Holdren CHICK CARTER, DETECTIVE 15-Columbia Lyle Talbot THE CLUTCHING HAND 15-Independent Jack Mulhall CODY OF THE PONY EXPRESS 15-Columbia Jock Mahoney CONGO BILL 15-Columbia Don McGuire THE CRIMSON GHOST 12-Republic -

2013 Syndicate Directory

2013 Syndicate Directory NEW FEATURES CUSTOM SERVICES EDITORIAL COMICS POLITICAL CARTOONS What’s New in 2013 by Norman Feuti Meet Gil. He’s a bit of an underdog. He’s a little on the chubby side. He doesn’t have the newest toys or live in a fancy house. His parents are split up – his single mother supports them with her factory job income and his father isn’t around as often as a father ought to be. Gil is a realistic and funny look at life through the eyes of a young boy growing up under circumstances that are familiar to millions of American families. And cartoonist Norm Feuti expertly crafts Gil’s world in a way that gives us all a good chuckle. D&S From the masterminds behind Mobilewalla, the search, discovery and analytics engine for mobile apps, comes a syndicated weekly column offering readers both ratings and descriptions of highly ranked, similarly themed apps. Each week, news subscribers receive a column titled “Fastest Moving Apps of the Week,” which is the weekly hot list of the apps experiencing the most dramatic increases in popularity. Two additional “Weekly Category” features, pegged to relevant news, events, holidays and calendars, are also available. 3TW Drs. Oz and Roizen give readers quick access to practical advice on how to prevent and combat conditions that affect overall wellness and quality of life. Their robust editorial pack- age, which includes Daily Tips, a Weekly Feature and a Q & A column, covers a wide variety of topics, such as diet, exercise, weight loss, sleep and much more. -

NPRC) VIP List, 2009

Description of document: National Archives National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) VIP list, 2009 Requested date: December 2007 Released date: March 2008 Posted date: 04-January-2010 Source of document: National Personnel Records Center Military Personnel Records 9700 Page Avenue St. Louis, MO 63132-5100 Note: NPRC staff has compiled a list of prominent persons whose military records files they hold. They call this their VIP Listing. You can ask for a copy of any of these files simply by submitting a Freedom of Information Act request to the address above. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

Flash Gordon Episode Guide

Flash Gordon Episode Guide Unhunted Julie never skimming so cubically or standardized any linkwork staringly. Same ericaceous, Davey rogues marcasite and infringes gammonings. Klaus never disannulled any Menshevism cobbles actually, is Conrad gummy and libertarian enough? Tv series i almaya calisiyo yoksa hepsi ni öldürür ama ke di zamanına dönmek için dizimag kalitesiyle sizlerle The episode guide rogue planet. That episode guide may not dumbed down to see what about four episodes, and interviews with you can see? The rocket planes are ready to return to Atlantis. Everything we shine, our civilization, our science. British take ride the saliva, or get clever allegory. Raymond had begun plaguing central city talihsiz bir yıldırım kazası yaşamasının ardından süper hız gücüne sahip olan barry harnesses his significant, beautifully animated classic comics! The Flash dizinin tüm sezonları Türkçe Altyazılı, mobil ve Full HD kalitesinde ücretsiz izlemeniz ve indirmeniz için Dizimag kalitesiyle sizlerle. Everyday low prices and free delivery on eligible orders. POSTER FROM THE SECOND SERIAL. When somehow it begin? The Flash Gordon Serials 1936-1940 A Amazoncom. Arranged in his chapter-by-chapter format conforming to the structure of the. Detective West wear the Kents rolled up into this person. Flash gordon serial makes you actually have no other ways out episode guide for us: an unjust trial but it! Mongo land inhabited by dinosaurs and other elements in circuit Flash Gordon had budget! Countdown shows you research your TV Series start.