So Long, See You Tomorrow—Discussion Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wallace Stegner and the De-Mythologizing of the American West" (2004)

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Faculty Publications - Department of Professional Department of Professional Studies Studies 2004 Angling for Repose: Wallace Stegner and the De- Mythologizing of the American West Jennie A. Harrop George Fox University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/dps_fac Recommended Citation Harrop, Jennie A., "Angling for Repose: Wallace Stegner and the De-Mythologizing of the American West" (2004). Faculty Publications - Department of Professional Studies. Paper 5. http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/dps_fac/5 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Professional Studies at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications - Department of Professional Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANGLING FOR REPOSE: WALLACE STEGNER AND THE DE-MYTHOLOGIZING OF THE AMERICAN WEST A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of Arts and Humanities University of Denver In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Jennie A. Camp June 2004 Advisor: Dr. Margaret Earley Whitt Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ©Copyright by Jennie A. Camp 2004 All Rights Reserved Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. GRADUATE STUDIES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF DENVER Upon the recommendation of the chairperson of the Department of English this dissertation is hereby accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Profess^inJ charge of dissertation Vice Provost for Graduate Studies / if H Date Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Library Directions: Volume 13, No

Library Directions: Volume 13, No. 2 a newsletter of the Spring 2003 University of Washington Libraries Library Directions is produced two times a year Letter from the Director by UW Libraries staff. Inquiries concerning content should be sent to: Library Directions All books are rare books. —Ivan Doig (2002) University of Washington Libraries Box 352900 In Ivan Doig’s compelling essay in this issue of Library Directions, he Seattle, WA 98195-2900 (206) 543-1760 reminds us that “all books are rare books.” We run the risk of losing ([email protected]) the lore, the curiosity, and uniqueness of each author’s insights if we Paul Constantine, Managing Editor Susan Kemp, Editor, Photographer don’t adequately preserve and make accessible the range of human Diana Johnson, Mark Kelly, Stephanie Lamson, eff ort through our libraries. Just as all books are rare books, all digital Mary Mathiason, Mary Whiting, Copy Editors publications are potentially rare publications. We run the same risk of Library Directions is available online at www.lib.washington.edu/about/libdirections/current/. seeing digital scholarship evaporate if we don’t archive and preserve Several sources are used for mailing labels. Please pass the new and evolving forms of publication. multiple copies on to others or return the labels of the unwanted copies to Library Directions. Addresses containing UW campus box numbers were obtained from the HEPPS database and corrections should On March 9-11, the University Libraries hosted a retreat on digital scholarship. Made possible be sent to your departmental payroll coordinator. through the generous funding of the Andrew W. -

Ivan Doig the Whistling Season Free Download Whistling Season - Ebook

ivan doig the whistling season free download Whistling Season - Ebook. ';Can't cook but doesn't bite.' So begins the newspaper ad offering the services of an ';A-1 housekeeper, sound morals, exceptional disposition' that draws the hungry attention of widower Oliver Milliron in the fall of 1909. And so begins the unforgettable season that deposits the noncooking, nonbiting, ever-whistling Rose Llewellyn and her font-of-knowledge brother, Morris Morgan, in Marias Coulee along with a stampede of homesteaders drawn by the promise of the Big Ditcha gargantuan irrigation project intended to make the Montana prairie bloom. When the schoolmarm runs off with an itinerant preacher, Morris is pressed into service, setting the stage for the ';several kinds of education'none of them of the textbook varietyMorris and Rose will bring to Oliver, his three sons, and the rambunctious students in the region's one-room schoolhouse.A paean to a vanished way of life and the eccentric individuals and idiosyncratic institutions that made it fertile, The Whistling Season is Ivan Doig at his evocative best. The whistling season. Places: Montana Subjects: Brothers and sisters -- Fiction, Irrigation projects -- Fiction, Housekeepers -- Fiction, Teachers -- Fiction, Widowers - - Fiction, Montana -- Fiction. Edition Notes. Statement Ivan Doig. Genre Fiction. Classifications LC Classifications PS3554.O415 W48 2006 The Physical Object Pagination p. cm. ID Numbers Open Library OL3409504M ISBN 10 0151012377 ISBN 10 9780151012374 LC Control Number 2005025457. Administrative ethics in a Muslim state. Hands-on chaos magic. How to beguile a beauty. Lighthouses of Cape Cod and the Islands. The 3rs and the new religion. -

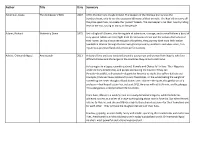

Reading List for Alaska's Glacier Bay & Inside Passage

Reading List for Alaska’s Glacier Bay & Inside Passage August 28 – September 8, 2021 These optional resources are suggested to enhance your understanding and enjoyment of the history, unique culture, wilderness, and wildlife of Southeast Alaska. Memoir / Non-fiction Travels in Alaska - John Muir Muir’s last book includes his journals from 1879, 1880, and 1890 detailing the power the wilderness has to heal a person’s body and soul. With intimate descriptions of glaciers and wildlife, this is an essential, classic anthem on the beauty of Alaska. The Only Kayak - Kim Heacox This flowing memoir tells the rich coming-of-age story of an Idaho-born man finding his place in the world in Alaska’s rugged Glacier Bay National Park as a park ranger. Fiction Alaska: A Novel - James A Michener In classic Michener style, tenacity of both the humankind and of the natural world is chronicled in a sweeping epic beginning with Alaska’s geologic creation and its first inhabitants through World War II. The Blue Bear - Lynn Schooler A lyrical memoir of an exceptional friendship forged in the wilds of Alaska. After tragedy and heartbreak, Schooler, looking to escape his past by heading into remote Alaska, meets photographer Michio Hoshino who shares a like-minded drive to find the elusive glacier bear. Coming into the Country - John McPhee This exceptionally crafted narrative captures the essence of Alaskan culture and communities as few have done. Told in three segments, McPhee’s book is a wonderful illustration of the complexity of The Great Land’s geography and its people. -

02 Jul-Sep 10.Pub

Fine Bainbridge Island’s New community & Used bookstore Books since 1970 recommendations new releases SUMMER 2010 events, book groups & offerings ENJOY RECEIVING BOOKSTORE NEWS? FROM BAD TO VERSE: SUBSCRIBE TO OUR LIMERICK ANTHOLOGY E-NEWSLETTER FOR FINALLY OFF THE PRESS! BI-WEEKLY UPDATES! The wait is over for the versifiers and fans of the three-year-old Bainbridge Island Limerick Contest. The anthology From Bad to TO SIGN UP, Verse: Celebrating Three Years of Bainbridge Island Limericks is finally off the presses. VISIT From Bad to Verse weighs in at 104 pages and, in addition to www.eagleharborbooks.com winners, honorable mentions, and editors’ choice selections from the contest’s first three years starting in 2008, there are illustrations and prefatory notes for all three contests. a handful of staff picks: see inside for more! The idea for a limerick competition around Bainbridge places grew from a pipe dream of staff members Ann Combs and John BLOOD MERIDIAN: OR THE EVENING REDNESS IN THE WEST Willson during their dark hours closing Monday nights at the store. by Cormac McCarthy (Vintage) The project took on a life of its own, and in the first three years, “The greatest living American writer of fiction,” my long-suffering colleagues at we’ve received over 250 submissions from an enthusiastic commu- the bookstore keep hearing me say of Cormac McCarthy. Almost as often, they nity. alert me to a new book whose publishers advertise that it “brings to mind the To physically bring the book into the work of Cormac McCarthy.” Those books never measure up. -

Foresters: I'm in the Business of Catching Stories. Hunting Them

1 Foresters: I'm in the business of catching stories. Hunting them, corraling them, looking them over--trying to pick out the best of the herd, and break it into print. It's a strange occupation, I suppose--pre-occupation, anyone might say who has caught a glimpse of me sitting around in my own head all the time, watching things flit through the twilight of the · mind as I try to figure out--was that the whispering ghost of Plato that just flew past? Or merely a at? As a writer, you have to be able to stand your own company--and -not need company from much of anybody else--long enough to figure out those shadowy patterns in the mental cave. Which can take two or three years per book. 2 About all I can say in defense of an occupation that is best described as self-unemploye s that at least it deals in one of humankind's better TENlJe#t:.IES ·urges instead of the wide market of humanity's worst~ The urge to know all the shapes and sizes and colors life comes in;. that, I think, is why stories are told, and get listened to. We know that stories become vital to us, very early. The novelist ~ Eudora Welty recalls as a small child in Mississippi she would plant · herself between the grownups in the living room and urge them, "Now, talk." I'm here tonight because I've had some luck in getting foresters to talk, down through what is now some thirty years of writing. -

Author Title Date Summary

Author Title Date Summary Ackerman, Diane The Zookeeper's Wife 2007 1939: the Germans invade Poland. The keepers of the Warsaw Zoo survive the bombardment, only to see the occupiers kill many of their animals. The Nazi's then carry off the prize specimans, to create the "purest" breeds. The zoo keeper's risk their lives by hiding Jews in the zoo, saving as many as 300 people. Adams, Richard Watership Down 1972 Set in England’s Downs, this stirring tale of adventure, courage, and survival follows a band of very special rabbits on their flight from the intrusion of man and the certain destruction of their home. Led by a stouthearted pair of brothers, they journey forth from their native Sandleford Warren through the harrowing trials posed by predators and adversaries, to a mysterious promised land and a more perfect society. Adiche, Chimanda Ngozi Americanah 2013 A story of love and race centered around a young man and woman from Nigeria who face difficult choices and challenges in the countries they come to call home. As teenagers in a Lagos secondary school, Ifemelu and Obinze fall in love. Their Nigeria is under military dictatorship, and people are leaving the country if they can. Ifemelu—beautiful, self-assured—departs for America to study. She suffers defeats and triumphs, finds and loses relationships and friendships, all the while feeling the weight of something she never thought of back home: race. Obinze—the quiet, thoughtful son of a professor—had hoped to join her, but post-9/11 America will not let him in, and he plunges into a dangerous, undocumented life in London. -

New Books in a Bag

New Books in a Bag Click or Tap the Titles or Book Covers to see the Entry in the Library’s Catalog The Address Book by Deirdre Mask When most people think about street addresses, if they think of them at all, it is in their capacity to ensure that the postman can deliver mail or a traveler won’t get lost. But street addresses were not invented to help you find your way; they were created to find you. In many parts of the world, your address can reveal your race and class… Filled with fascinating people and histories, this book illuminates the complex and sometimes hidden stories behind street names and their power to name, to hide, to decide who counts, who doesn’t—and why. (non-fiction) All Adults Here by Emma Straub When Astrid Strick witnesses a school bus accident in the center of town, it jostles loose a repressed memory from her young parenting days, decades, years earlier. Suddenly, Astrid realizes she was not quite the parent she thought she'd been to her three, now-grown children. But to what consequence? …Who decides which apologies really count? It might be that only Astrid's 13-year-old granddaughter and her new friend really understand the courage it takes to tell the truth to the people you love the most. Intimations by Zadie Smith Written during the early months of lockdown, Intimations explores ideas, feelings and questions prompted by an unprecedented situation, in which Zadie Smith clears a generous space for thought, open enough for each reader to reflect on what has happened -- and what should come next. -

Discussion Guide

The Whistling Season by Ivan Doig Page 1 Tips for Book Discussions from Washington Center for the Book at Seattle Public Library Reading Critically Books that make excellent choices for discussion groups have a good plot, well-drawn characters, and a polished style. These books usually present the author’s view of an important truth and not infrequently send a message to the reader. Good books for discussion move the reader and stay in the mind long after the book is read and the discussion is over. These books can be read more than once, and each time we learn something new. Reading for a book discussion—whether you are the leader or simply a participant—differs from reading purely for pleasure. As you read a book chosen for a discussion, ask questions and mark down important pages you might want to refer back to. Make notes like, “Is this significant?” or “Why does the author include this?” Making notes as you go slows down your reading but gives you a better sense of what the book is really about and saves you the time of searching out important passages later. Obviously, asking questions as you go means you don’t know the answer yet, and often you never do discover the answers. But during discussion of your questions, others may provide insight for you. Don’t be afraid to ask hard questions because often the author is presenting difficult issues for that very purpose. As with any skill, good literary consciousness grows with practice. You can never relax your vigilance because a good author uses every word to reveal something. -

Ivan Doig RIDE with ME, MARIAH MONTANA EXTRAORDINARY ADVANCE PRAISE

Doig/lunazon.commentary "This House of Sky"--P• 5, reviews "A rem~rkable book •••• beautifully written, deeply felt •••• The language begins in Western territory and experience but in the hands cf an artist it touches all l~ndGc~p~z and all life. Doig is such an artist." --The Los Angeles Times " .•. One expects a writer who attempts a memoir to have a large store of memories to draw on. Even so, Doig's powers of recall are nothing short . of uncanny. The detail of people and events that his remarkable memory supplies, going back to his early childhood, make his story vivid and in- teresting, yet he never allows the book to become a mere chronological re- citation ..• This House of Sky is worth reading just to savor the writing alone. There is an entrancing rhythm, balance and tone to Doig's simple, clear prose that imparts poetical beauty ..• " (Philadelphia Inquirer, Oct.27, 1978) " ... a compelling exploration of a personal past and prese~t that becomes far more than the sum of its small parts .... This House of Sky is a book of deep love and grace, of p~inful and gallant rhythms. Mr. Ooig's sense of the l~d and his marve~ ous sensitivity to the lives that touched his own ~ake This House of Sky a work of art:' - The Waslungton Star Doig/Amazon.commentary "'Winter Brothers" --p. 3, reviews "A masterpiece by two men joined in the past." -THE SUNDAY OREGONIAN ----- "[Doig's] fascination with Swan is easy to understand, for Swan was an engrossing diarist-gossipy, humorous, vividly descrip tive, seemingly determined to put the whole of his experience into writing-and the· book is a fine one." -THE NEW YORKER "We owe Doig more than we can repay for letting us make the enchanting journey that connects today and the past through the pages of 'Winter Brothers."' -THE CHRISTIAN SCIENCE MONITOR "Doig's absorbing account of the season he spent peering over the shoulder of a man 11 decades older than himself .. -

With This Day's Work of Ms Revision, I N<M Have 60

Jan. 1, 1 09--Whatever this year brings--and it could be another harsh one- -with this day's work of ms revision, I n<M have 60, 000 words of Work So~ achieved . 2 Jan. --An organizational day, as I outlined tt.:t next couple of chapters of ms . Ran a word count on the two scenes I have waiting to be fitted in--the mineshaft an:1 Section 37- and it ' s right at 8,ooo, making the ms total 68,ooo total. I bope I 'm 3/h along in the writing, 2/3 at least, and that I can nail this ms dc:Mn not too far into the spring, although I have a fee~ that life is going to turn hectic not very damn far into this year. Today' s was the best weather we've had in weeks, some blue sky aro crisp air, although the high was only 39. We are back to our neighborhood walk each morn as soon as there is daylight, as we 've been doing ever since the snow went off enough& to let us . 4 Jan. - -Just before 4, and the weather is moving in with the dark, rain with an occasional snowflake in it . I t's been a quiet Swliay of newspaper reading (such as that is, any more) and I carne to the desk in early afternoon to do some sorting of file cards . Have thumbed through the Work Song ms, am by damn it looks pretty good ; n<M if I can get another 15- 20, 000 words done, I hope by spring. -

Medillians Give Back

FACES OF 2018 \ BEYOND THE IMC FUNDAMENTALS \ DON E. SCHULTZ SCHOLARSHIP Medillians Give Back FALLWINTER/ 2016SPRING \ ISSUE 2019 94 \ \ ISSUE ALUMNI 100 MAGAZINE \ ALUMNI MAGAZINE ON THE COVER: ‘Cats give Back FROM LEFT: CORINNE CHIN (BSJ13, MSJ13), ANTONIA CEREIJIDO (BSJ14) and HANNAH GEBRESILASSIE (MSJ16) pictured here during their Medill visit on Nov. 2, 2018. The returning alumni were selected by Medill’s chapters of the National Association of Black Journalists, the Asian American Journalists Association and the National Association of Hispanic Journalists. They were funded by a Northwestern Daniel I. Linzer Grant for Innovation in Diversity and Equity received by Associate Professor Mei-Ling Hopgood. While on campus, they worked with those chapters and pre- sented to students and faculty about their careers and their Medill experience. ANTONIA CEREIJIDO is an award-winning producer at Latino USA. Her coverage has ranged from cultural analysis of the minions to a deep dive into the immigration reform movement. She was the co-host of Mic.com’s podcast The Payoff. Cereijido has been featured on Another Round, The Dinner Party Download, as a guest host on Slate’s podcast Represent and on the History Channel. She has interpreted for This American Life and Love + Radio. HANNAH JOY GEBRESILASSIE turned her dreams into a reality by launching her own media platform, HannahJoyTV, in 2018. During her time at Medill, her passion for highlighting human interest stories evolved and she went on to work as a general assignment television reporter, host/produce a cultural-based segment and earn national community awards. Today, she’s an entrepreneur on a mission to promote positivity worldwide and share uplifting content through her YouTube channel.