November 2002

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit

Case: 12-1298 Document:2012 46 - 1298 Page: 1 Filed: 09/27/2012 In The United States Court Of Appeals For The Federal Circuit ORGANIC SEED GROWERS AND TRADE ASSOCIATION, ORGANIC CROP IMPROVEMENT ASSOCIATION INTERNATIONAL, INC., THE CORNUCOPIA INSTITUTE, DEMETER ASSOCIATION, INC., CENTER FOR FOOD SAFETY, BEYOND PESTICIDES, NAVDANYA INTERNATIONAL, MAINE ORGANIC FARMERS AND GARDENERS ASSOCIATION, NORTHEAST ORGANIC FARMING ASSOCIATION OF NEW YORK, NORTHEAST ORGANIC FARMING ASSOCIATION/MASSACHUSETTS CHAPTER, INC., NORTHEAST ORGANIC FARMING ASSOCIATION OF NEW HAMPSHIRE, NORTHEAST ORGANIC FARMING ASSOCIATION OF RHODE ISLAND, CT NOFA, NORTHEAST ORGANIC FARMING ASSOCIATION OF VERMONT, RURAL VERMONT, OHIO ECOLOGICAL FOOD & FARM ASSOCIATION, FLORIDA CERTIFIED ORGANIC GROWERS AND CONSUMERS INC., SOUTHEAST IOWA ORGANIC ASSOCIATION, MENDOCINO ORGANIC NETWORK, NORTHEAST ORGANIC DAIRY PRODUCERS ALLIANCE, MIDWEST ORGANIC DAIRY PRODUCERS ALLIANCE, WESTERN ORGANIC DAIRY PRODUCERS ALLIANCE, CANADIAN ORGANIC GROWERS, PEACE RIVER ORGANIC PRODUCERS ASSOCIATION, FAMILY FARMER SEED COOPERATIVE, SUSTAINABLE LIVING SYSTEMS, GLOBAL ORGANIC ALLIANCE, FOOD DEMOCRACY NOW!, FARM-TO-CONSUMER LEGAL DEFENSE FUND, WESTON A. PRICE FOUNDATION, MICHAEL FIELDS AGRICULTURAL INSTITUTE, FEDCO SEEDS INC., ADAPTIVE SEEDS, LLC, SOW TRUE SEED, SOUTHERN EXPOSURE SEED EXCHANGE, MUMM'S SPROUTING SEEDS, BAKER CREEK HEIRLOOM SEED CO., LLC, COMSTOCK, FERRE & CO., LLC, SEEDKEEPERS, LLC, SISKIYOU SEEDS, COUNTRYSIDE ORGANICS, WILD GARDEN SEED, CUATRO PUERTAS, SEED WE NEED, ALBA RANCH, WILD -

Comprehensive Teacher Evaluation & Professional Development System Summer 2015

POJOAQUE VALLEY SCHOOLS COMPREHENSIVE TEACHER EVALUATION & PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT SYSTEM SUMMER 2015 Strengthening our future one student at a time! 1574 State Road 502 West Santa Fe, New Mexico 87506 Central Office: (505) 455-2282 Fax: (505) 455-7152 www.pvs.k12.nm.us 0 POJOAQUE VALLEY SCHOOL DISTRCT Comprehensive Teacher Evaluation and Professional Development System TABLE OF CONTENTS Section 1 (Updated Summer 2015) Page Introduction 3 Calendar and Schedule 4 Crosswalk of NM Teacher Competencies and NM TEACH Domains 6 Frequency of Scoring 7 Concerns/Complaints 7 Third Observer 8 Growth Plan 8 Appeal of Evaluations 9 Development of Growth Plan 9 Link to the 3 Tier System 10 The Difference Between Highly Effective and Exemplary 10 Format and Components of Lesson Plans 10 Effective Strategies 11 Marzano’s Academic Vocabulary for Student Success 10 Grades K through 2 11 Grades 3 through 5 28 Grades 6 through 8 56 Grades 9 through 12 83 Four Square Activity 111 Academic Literacy Notebooks 113 ACE Strategies 115 Sections 2 through 5 contain the observation protocol with clear and expanded definitions and examples Section 2 123 Domain 1 Elements A through F Planning and Preparation Section 3 163 Domain 2 Elements A through E Creating an Environment for Learning Section 4 191 Domain 3 Elements A through E Teaching for Learning Section 5 225 Domain 4 Elements A through F Professionalism 1 POJOAQUE VALLEY SCHOOL DISTRICT BOARD OF EDUCATION Mr. Jon Paul Romero President Mr. Fernando Quintana Vice-President Mr. Toby Velasquez Secretary Ms. Sharon Dogruel Member Mr. Jeffery Atencio Member Dr. -

October 12, 7:30 Pm

GRIFFIN CONCERT HALL / UNIVERSITY CENTER FOR THE ARTS Featuring the music of Wilson, Dvorak, Persichetti, Sousa, Ravel/Frey, and Schwantner OCTOBER 12, 7:30 P.M. THE COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY WIND SYMPHONY PRESENTS: FIND YOUR STATE: State of Inspiration REBECCA PHILLIPS, Conductor ANDREW GILLESPIE, Graduate Student Conductor RICHARD FREY, Guest Conductor CORRY PETERSON, Guest Conductor Fanfare for Karel (2017) / DANA WILSON Serenade in d minor, op. 44 (1878) / ANTONÍN DVOŘÁK Moderato, quasi Marcia Finale Symphony for Band (Symphony No. 6), op. 69 (1956) / VINCENT PERSICHETTI Adagio, Allegro Adagio sostenuto Allegretto Vivace Andrew Gillespie, graduate guest conductor Nobles of the Mystic Shrine (1923) / JOHN PHILIP SOUSA Corry Peterson, guest conductor, Director of Bands, Poudre High School Ma mére l’Oye (Mother Goose Suite) (1910) / MAURICE RAVEL trans. by Richard Frey Pavane de la Belle au bois dormant (Pavane of Sleeping Beauty) Petit Poucet (Little Tom Thumb) Laideronnette, impératrice des pagodes (Little Ugly Girl, Empress of the Pagodas) Les entretiens de la belle et de la bête (Conversation of Beauty and the Beast) Le jardin féerique (The Fairy Garden) Richard Frey, guest conductor From a Dark Millennium (1980) / JOSEPH SCHWANTNER The 2017-18 CSU Wind Symphony season highlights Colorado State University's commitment to inspiration, innovation, community, and collaboration. All of these ideals can clearly be connected by music, and the Wind Symphony begins the season by featuring works that have been inspired by other forms of art, including folk songs, hymns, fairy tales, and poems. We hope that you will join us to "Find Your State” at the UCA! NOTES ON THE PROGRAM Fanfare for Karel (2017) Dana Wilson Born: 4 February 1946, Lakewood, Ohio Duration: 2 minutes Born in Prague on August 7, 1921, Karel Jaroslav Husa was forced to abandon his engineering studies when Germany occupied Czechoslovakia in 1939 and closed all technical schools. -

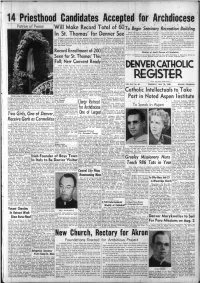

REGISTER Modate the Increased Enrollment

14 Priesthood Candidates Accepted for Archdiocese Patron of Peace + + + + + Will Make Record Total of 60 To Begin Seminary Recreation Building W ork will begin this fall on new recreation ing. It will contain two bowling alleys and other In St. Thomas' for Denver See facilities for Sf. Thomas’ seminary, Denver. A base recreation facilities. Also to be constructed outdoors ment recreatidn hall will be constructed south o f on the grounds arc four new handball courts, Fourteen candidates, have been accepted for entrance into St. Thomas’ seminary this the new convtot on the seminary grounds on the which will be erected cast of the new gymnasium. fall to begin preparation for the priesthood in the Archdiocese of Denver, Archbishop Ur site pf the old; baseball field (which will be moved Will Coit $45,000 ban J. Vehr announced this week. Of the students, nine are from Denver, two from Brigh south). The superstructure o f the building, a large , The cost of the basement building will be about ton, one each from Loveland and Glenwood Springs, all in the Archdiocese of Denver; gymhasium, vlill be added later. $45,000. The building will be of considerably bet and one from Chicago. The new fecreation building is made necessary ter construction than the one planned earlier, in + ■ + + + ' + Archbishop Vehr has announced by the increased enrollment at the seminary, which the interests both of durability and of harmony with that this year’s enrollment of sem is crowding oiit recreation rooms in the ipain build the present seminary buildings. inarians for the Archdiocese of Denver will number 60, a new rec Record Enrollment of 200 ord. -

PAX MUSICAMUSICA 2011 Touring Year • Client Tour Stories 2011 Highlights What’S Inside Baltimore Symphony Orchestra

Classical Movements, Inc. PAXPAX MUSICAMUSICA 2011 Touring Year • Client Tour Stories 2011 Highlights What’s Inside Baltimore Symphony Orchestra ........... 9 202 Concerts Canterbury Youth Chorus ................. 15 Arranged College of William and Mary ............ 10 Worldwide Collège Vocal de Laval ...................... 11 Read more inside! Children’s Chorus of Sussex County ............................... 7 Dallas Symphony Orchestra Proud to Start and Chorus .................................... 9 Our 20th Year Drakensberg Boys’ Choir .................... 2 Eric Daniel Helms Classical Movements New Music Program ...................... 5 Rwas established in El Camino Youth Orchestra ................ 7 1992, originally Fairfield County Children’s Choir .......................... 15 operating as Blue George Washington University Choir .. 7 Heart Tours and Greater New Orleans providing exclusive Youth Orchestra ............................ 4 tours to Russia. Harvard-Radcliffe Orchestra ............... 3 Ihlombe! South African Rapidly, more Choral Festival ............................. 14 countries were added, Marin Alsop (Baltimore Symphony Orchestra Music Director), David Los Angeles Children’s Choir ........... 15 attracting more and Rimelis (Composer), Dan Trahey (OrchKids Director of Artistic Melodia! South American Program Development) and Neeta Helms (Classical Movements Music Festival ................................ 6 more extraordinary President) at the premiere of Rimelis’ piece OrchKids Nation Minnesota Orchestra .......................... -

Works by George Perle, David Del Tredici, and Nicholas Thorne New World 80380-2

Works by George Perle, David Del Tredici, and Nicholas Thorne New World 80380-2 The vastly divergent reactions to twelve-tone composition of George Perle, David Del Tredici and Nicholas Thorne are a vivid reflection not only of their different generations, but of the unfolding of musical style change in America. Perle, born in 1915 and educated here at a time when twelve-tone composition was little understood, felt the urge to revise Schoenberg's method so as to reconcile serial chromaticism with the hierarchical elements of tonal practice. The system he evolved, known as “twelve-tone tonality,” has been the basis of most of his compositions until 1969, and all since. Del Tredici, born in 1937, studied at Princeton at a time when serialism had become dogma. Yet he eventually repudiated the technique and turned to a highly eccentric form of tonality. Thorne, born in 1953, gave little thought to twelve-tone composition. “It was the generation before me who had this monkey on its back,” he says. Instead, Thorne came to maturity amid the welter of styles, from minimalism to neo-Romanticism, that characterized America during the 1970s. All three attitudes offer us invaluable insights into the composers and their music. In some circles George Perle is known as a musicologist, particularly for his pathbreaking studies of Alban Berg. In other circles, he is viewed as a theorist, a coherent codifier and radical reviser of serial technique. But he insists that both these pursuits have been sidelines to composition, and his music belies the popular misconception that art conceived under the wing of academia need be abstruse or inaccessible. -

By Joseph Schwantner: an Exploration of Trajectory As an Organizing Principle for Drama, Motive, and Structure

New Morning For The World ("Daybreak Of Freedom") By Joseph Schwantner: An Exploration Of Trajectory As An Organizing Principle For Drama, Motive, And Structure By Mark Feezell, Ph.D. ([email protected], www.drfeezell.com) Copyright © 2002 by Mark Feezell. All Rights Reserved. Used on this site by permission of the author. This essay explores techniques found in Joseph Schwantner's 1982 composition New Morning for the World ("Daybreak of Freedom"). Schwantner's piece, in which a speaker performs the part of Martin Luther King, Jr. using texts from his speeches and writings, establishes dramatic, motivic, and structural trajectories1 through the interactions of the speaker and the orchestra. Each of the three trajectories, dramatic/narrative, motivic, and structural, exert their influence continuously throughout Schwantner's piece. Simultaneously, each trajectory supports and influences the others. Joseph Schwantner (born 1943) is an American composer2 who earned composition degrees from the American Conservatory of Music in Chicago (BM, 1964) and Northwestern University (MM 1966, DM 1968). Elements that pervade his mature works include "a fascination with timbre, extreme instrumental range, juxtaposed instrumental groupings, pedal points, and a 1 A trajectory is the directed evolution of a set of related musical parameters. 2 For background and analysis on other Schwantner works, see, for example, Cynthia Folio's article "The synthesis of traditional and contemporary elements in Joseph Schwantner's 'Sparrows,'" Perspectives of New Music, -

18-19 REP SEASON | WINTER 6O

18-19 REP SEASON | WINTER 6o The Music Man The Crucible A Doll’s House, Part 2 Sweat Noises Off The Cake Sweeney Todd Around the World in 80 Days asolorep asolorep PRODUCING ARTISTIC DIRECTOR MICHAEL DONALD EDWARDS MANAGING DIRECTOR LINDA DiGABRIELE PROUDLY PRESENTS BY Arthur Miller DIRECTED BY Michael Donald Edwards Scenic Design Costume Design Lighting Design Sound Design & Original Composition LEE SAVAGE TRACY DORMAN JEN SCHRIEVER FABIAN OBISPO Hair/Wig & Make-up Design New York Casting Chicago Casting Local Casting Voice & Dialect Coach MICHELLE HART STEWART/WHITLEY CASTING SIMON CASTING CELINE ROSENTHAL PATRICIA DELOREY Fight Director Production Stage Manager Stage Manager & Fight Captain Assistant Stage Manager Dramaturg ROWAN JOHNSON NIA SCIARRETTA* DEVON MUKO* JACQUELINE SINGLETON* PAUL ADOLPHSEN Directing Fellow Music Coach Stage Management Apprentice Stage Management Apprentice Dramaturgy & Casting Apprentice TOBY VERA BERCOVICI LIZZIE HAGSTEDT CAMERON FOLTZ CHRISTOPHER NEWTON KAMILAH BUSH The Crucible is presented by special arrangement with Dramatists Play Service, Inc., New York Directors are members of the Stage Directors and Choreographers Society; Designers are members of the United Scenic Artists Local USA-829; Backstage and Scene Shop Crew are members of IATSE Local 412. The video and/or audio recording of this performance by any means whatsoever is strictly prohibited. CO-PRODUCERS Gerri Aaron • Nancy Blackburn • Tom and Ann Charters • Annie Esformes, in loving memory of Nate Esformes • Shelley and Sy Goldblatt Nona -

WIPAC's Gala Fundraiser: “A Sparkling Night on the Riviera”

ARTS AND CULTURE, COMMUNITY NEWS WIPAC’s Gala Fundraiser: “A Sparkling Night on the Riviera” by Lisa McFarren-Polgar • November 26, 2017 The Washington International Piano Arts Council hosted an enchanting evening of music, dance and graciousness at their benefit Gala “Le Bal des Lumieres” held at the Columbia Country Club in Chevy Chase. Reminiscent of “La Belle Epoque” with a contemporary infusion, the doyen and doyenne of WIPAC, Mr. and Mrs. John and Chateau Gardecki, welcomed their guests to celebrate yet another year of WIPAC’s continuing support of pianists of the classical piano repertoire. Indeed, it was “A Sparkling Night on the Riviera,” with its simulated casino night and a silent auction of gifts donated by WIPAC supporters. Attended by WIPAC’s loyal supporters the Gala was Co-Chaired by Robin Phillips and Timothy Thomas. WIPAC President Clayton Eisinger eloquently expressed a sense of pride in being a part of the WIPAC organization and pledged his continued support for WIPAC and the vision of its Founders, Chateau and John Gardecki to promote the art of piano performance. Paying tribute to the inspiration that WIPAC has given to pianists for 16 years, the winner of WIPAC’s first 2003 International Piano Artists Competition, pianist-composer Paul Anthony Romero spoke of the positive impact that the competition had on his life as a musician. Performing with saxophonist Dr. Brock Summers, Paul Romero dazzled the audience with his beautiful arrangement of a medley of George Gershwin’s “Porgy and Bess” tunes mixed with Rachmaninoff’s 2nd Symphony, followed by original works by Paul Romero for piano and saxophone. -

Santa Clara University School of Law Commencement 2021

SCHOOL2021 OF LAW COMMENCEMENT Ad Majorem Dei Gloriam The Jesuit Ideal of Serving Others In its One Hundred Seventieth Year SANTA CLARA UNIVERSITY School of Law Commencement May Twenty-Second Two Thousand and Twenty-One Santa Clara University School of Law Founded 1911 C7 '\ ''. j ,' '·' SANTA CLARA UNIVERSITY EDUCATING CITIZENS AND LEADERS WHO WILL BUILD A MORE HUMANE, JUST, AND SUSTAINABLE WORLD. iiiiR THE SANTA CLARA HERITAGE n January 12, 1777, six months formerly of the Oregon mission territory, In that same year, the School of after the signing of the Declaration to open a college at Mission Santa Clara. Engineering was founded, and courses Oof Independence, two Franciscan The property was transferred to the in the humanities and sciences were padres, Tomás de la Peña and José Jesuit order and classes began on March expanded. Responding to urban growth Antonio Murguia, founded the eighth of 19, 1851. Thus, Santa Clara became in the Santa Clara Valley, the University California’s original 21 missions along the first institution of higher learning in established a School of Business in the banks of the Rio Guadalupe. Mission the state of California. During its first 1926. Today, Santa Clara University Santa Clara de Asís, as they named it, complete academic year, 1851–52, consists of the College of Arts and served as a spiritual center and school Father Nobili and a few Jesuits and lay Sciences, the Jesuit School of Theology, for the Indians and early settlers. Besides teachers offered instruction in reading, the Leavey School of Business, and providing religious instruction for both writing, and foreign languages. -

MUSC 2014.11.18 Windsymprog

UPCOMING EVENts Jazz Ensembles Concert: With Special Guest Paul Hanson, Bassoon CSU WIND SYMPHONY 11/20 • Griffin Concert Hall • 7:30 pm Dr. Rebecca Phillips, Conductor Zachary Fruits, Graduate Conducting Assistant Jazz Combos Concert: Jazz Combos I, II, and III 12/3 • Griffin Concert Hall • 7:30 pm ANNual HOLIDAY SPectacular PROGRAM 12/4 • Griffin Concert Hall • 7:00 pm 12/5 • Griffin Concert Hall • 2:00 pm & 7:00 pm & Frank Ticheli Nitro (2006) THEATRE: A Year with Frog and Toad By Robert & Willie Reale Directed by: Walt Jones Gustav Holst Hammersmith, Op. 52 (1930) 12/4, 5, 6, 7, 11, 12, 13, 14 • University Theatre • 7:30pm UCA 12/6, 7,13,14 • University Theatre • 2:00 pm Leonard Bernstein Candide Suite (1956/1993) Concert Orchestra Concert: With Zachary arr. by Clare Grundman Bush, Erik Deines, and Andrew Miller, Bass Soloists I. The Best of All Possible Worlds 12/7 • Organ Recital Hall • 7:30 pm • FREE II. Westphalia III. Auto-da-fe IV. Glitter and Be Gay Symphonic Band Concert MARILYN V. Make Our Garden Grow 12/10 • Griffin Concert Hall • 7:30 pm COCKBURN Zachary Fruits, Graduate Conducting Assistant event calendar • e-newsletter registration Meet Me at the UCA Season “Green” Sponsor Andy Francis Threnody for Haiti (2010) www.uca.colostate.edu General Information: (970) 491-5529 INTERMISSION Tickets: (970) 491-ARTS (2787) www.CSUArtsTickets.com UNIVERSITY INN Darius Milhaud Le Création du Monde (1923) Katelyn Vincent, alto saxophone; Ji Hye Chung, violin; Elizabeth Furuiye, violin; Lydia Hynson, cello; Drew Miller, string bass Joseph Schwantner …and the mountains rising nowhere (1977) Dr. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Jim Eninger\My Documents\Chamber

Classical Crossroads, Inc. and First Lutheran Church & School in Torrance Present Two Concert Series The Interludes Beverly Hills Auditions Winners (also presented Fridays in Encinitas Public Library and Sundays in winter/spring 2015 in Beverly Hills’ Greystone Mansion) Free, donations welcome Saturday, September 20, 2014 at 3:30 p.m. Saturday, February 21, 2015 at 3:30 p.m. Violinist ETIENNE GARA New York City-based Pianist HAYK ARSENYAN A laureate of the Fondation Marcel Bleustein-Blanchet in France, Hayk’s May 2011 recital was the New York Times’ “Choice of the Etienne is continuing his graduate studies with Midori at the Week” and reviewed as “One of the coolest events in NYC to go to.” USC Thornton School of Music. Saturday, March 21, 2015 at 3:30 p.m. Saturday, October 25, 2014 at 3:30 p.m. MÜHLFELD TRIO THE UPSIDE — DIANA MORGAN flute, BENJAMIN MITCHELL clarinet, MICHAEL KAUFMAN cello, LAUREN KOSTY vibraphone & percussion, BRENDAN WHITE piano STEPHEN PFEIFER double bass The Mühlfeld Trio takes its name from the great clarinetist Richard One of L.A.’s premier classical/jazz crossover ensembles performs Mühlfeld (1856–1907), who so inspired Johannes Brahms near the selections from Bach to Brubeck. end of his life that he came out of retirement. ~ and ~ Saxophonist RUSSELL VEIRS Saturday, April 18, 2015 at 3:30 p.m. A rising star, Russell earned his Doctor of Musical Arts at UCLA AMBER QUARTET from the Colburn School under renowned saxophonist Douglas Masek. EDUARDO RIOS and MADELEINE VAILLANCOURT violins, BENJAMIN MANIS cello, TANNER MENEES viola Saturday, November 15, 2014 at 3:30 p.m.