Hamlet 2008 Scrapbook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Three Eras, Two Men, One Value: Fides in Modern Performances of Shakespeare’S

Three Eras, Two Men, One Value: Fides in Modern Performances of Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra Depictions of Marc Antony and Caesar Augustus have changed dramatically between the first and twenty-first centuries, partially because of William Shakespeare’s seventeenth-century play Antony and Cleopatra. In 2006 and 2010, England’s Royal Shakespeare Company staged vastly different interpretations of this classically influenced Shakespearean text. How do the modern performances rework ancient views of Antony and Augustus, particularly in light of the ancient Roman value fides (loyalty or good faith)? This paper answers that question by examining the intersections between Greco-Roman literary-historic narratives – as received in Shakespeare’s early modern play – and the two modern performances. The contemporary versions of Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra create contrasting constructions of Antony and Augustus by modernizing the characters and/or their worlds. The 2006 rendition (directed by Gregory Doran) presents an explosive but weak-willed Antony (Sir Patrick Stewart) and a prudish yet petulant Augustus (John Hopkins). On the other hand, the 2010 adaptation (directed by Michael Boyd) shows a hotheaded and frank Antony (Darrell D’Silva) who struggles against a cold and manipulative Augustus (John Mackay). Both performances reveal the complexity of these ancient figures as the men engage with and evaluate claims upon their familial, societal, and personal fides. Representations of Antony and Augustus necessarily involve fides, though classical accounts do not always feature this term. As military and political leaders, both men led lives filled with decisions about loyalty, specifically what deserved it and in what degree. The modern dramatizations further underscore fides in their portrayals of Antony and Augustus. -

Julius Caesar

BAM 2013 Winter/Spring Season Brooklyn Academy of Music BAM, the Royal Shakespeare Company, Alan H. Fishman, and The Ohio State University present Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Julius Vice Chairman of the Board Karen Brooks Hopkins, President Joseph V. Melillo, Caesar Executive Producer Royal Shakespeare Company By William Shakespeare BAM Harvey Theater Apr 10—13, 16—20 & 23—27 at 7:30pm Apr 13, 20 & 27 at 2pm; Apr 14, 21 & 28 at 3pm Approximate running time: two hours and 40 minutes, including one intermission Directed by Gregory Doran Designed by Michael Vale Lighting designed by Vince Herbert Music by Akintayo Akinbode Sound designed by Jonathan Ruddick BAM 2013 Winter/Spring Season sponsor: Movement by Diane Alison-Mitchell Fights by Kev McCurdy Associate director Gbolahan Obisesan BAM 2013 Theater Sponsor Julius Caesar was made possible by a generous gift from Frederick Iseman The first performance of this production took place on May 28, 2012 at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Leadership support provided by The Peter Jay Stratford-upon-Avon. Sharp Foundation, Betsy & Ed Cohen / Arete Foundation, and the Hutchins Family Foundation The Royal Shakespeare Company in America is Major support for theater at BAM: presented in collaboration with The Ohio State University. The Corinthian Foundation The Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation Stephanie & Timothy Ingrassia Donald R. Mullen, Jr. The Fan Fox & Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, Inc. Post-Show Talk: Members of the Royal Shakespeare Company The Morris and Alma Schapiro Fund Friday, April 26. Free to same day ticket holders The SHS Foundation The Shubert Foundation, Inc. -

Some Thoughts Surrounding 2016Production of the Tempest

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by DSpace at Waseda University Some thoughts surrounding 2016 production of The Tempest UMEMIYA Yu The following note shows the result of an on going research on the play by William Shakespeare: The Tempest. The 2016 production at the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC), one of the leading theatre companies in England, demonstrated another innovative version of the play on their main stage in Stratford-upon-Avon, followed by its tour down to Barbican theatre in London in 2017. It did not include an extraordinary interpretation or unique casting pattern but demonstrated the extended development of technology available on stage. This note introduces the feature and the reception of the production in the latter half, with a brief summary of the play and a survey of the performance history of The Tempest in the first half. The story of The Tempest Compared to other plays by Shakespeare, The Tempest is a rare example that follows the classical idea of three unities of time, place and action, deriving from 1 Aristotle, then prescribed by Philip Sydney in Renaissance England . The similar 2 structure has already practiced in The Comedy of Errors in 1594 , but while this early comedy is often described as a simple farce, The Tempest contains various complications in terms of plots and theatrical possibilities. The story of The Tempest opens with a storm at sea, conjured by the magic of Prospero, the main character of the play. He is manipulating the tempest from the 一二七nearby island where he lives with his daughter, Miranda, and shares the land with two other fantastic creatures, Ariel and Caliban. -

Theatre Access

ACCESS MATTERS Welcome to our Winter 2017 Access Matters, where you can find out about our access provision and our forthcoming assisted performances. Old stories are so often the ones we return to again and again to make sense of the world around us. As our Rome collection of plays continues into autumn, we see how Shakespeare, his contemporaries and modern writers also seek inspiration in history and myth to fuel stories that still resonate in 2017. Rome Season Director, Angus Jackson, returns to the Royal Shakespeare Theatre with the last of Shakespeare’s Roman plays, Coriolanus. Sope Dirisu – a rising talent who originally emerged through our very own Open Stages programme – is an exciting Coriolanus. Another new voice emerges in the Swan Theatre: Kimberley Sykes, Associate Director on our Dream 16 tour makes her RSC directorial debut with Christopher Marlowe’s tragedy, Dido, Queen of Carthage. Our Swan Theatre season continues with a new adaptation of Robert Harris’ epic Cicero trilogy by Mike Poulton (Wolf Hall/Bring Up the Bodies). This thrilling political saga tells the story of the rise Communications Design by RSC Visual and fall of the great Roman orator, Cicero. Ovid was Shakespeare’s favourite poet and references to these classical stories litter his plays. We have lost our cultural familiarity with many of these and I feel passionate about reigniting our understanding of these wonderful fables. Over three weeks, eight events will explore Ovid’s stories from many angles. New voices resound around The Other Place once again with two Mischief Festivals. The first, in May, sees the return to the RSC of writer Tom Morton-Smith (Oppenheimer, 2015) and the co-writing debut of Matt Hartley and Kirsty Housley with a double bill of provocative short plays. -

Shakespeare in South Africa: an Examination of Two Performances of Titus Andronicus in Apartheid and Post- Apartheid South Africa

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2017 Shakespeare in South Africa: An Examination of Two Performances of Titus Andronicus in Apartheid and Post- Apartheid South Africa Erin Elizabeth Whitaker University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Other English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Whitaker, Erin Elizabeth, "Shakespeare in South Africa: An Examination of Two Performances of Titus Andronicus in Apartheid and Post-Apartheid South Africa. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2017. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4911 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Erin Elizabeth Whitaker entitled "Shakespeare in South Africa: An Examination of Two Performances of Titus Andronicus in Apartheid and Post- Apartheid South Africa." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in English. Heather A. Hirschfeld, Major Professor We have read -

Shakespeare Survey: Writing About Shakespeare, Volume 58 Edited by Peter Holland Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521850746 - Shakespeare Survey: Writing about Shakespeare, Volume 58 Edited by Peter Holland Frontmatter More information SHAKESPEARE SURVEY © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521850746 - Shakespeare Survey: Writing about Shakespeare, Volume 58 Edited by Peter Holland Frontmatter More information ADVISORY BOARD Jonathan Bate Russell Jackson Margreta de Grazia John Jowett Janette Dillon Kathleen E. McLuskie Michael Dobson A. D. Nuttall R. A. Foakes Lena Cowen Orlin Andrew Gurr Richard Proudfoot Terence Hawkes Ann Thompson Ton Hoenselaars Stanley Wells Assistant to the Editor Paul Prescott (1) Shakespeare and his Stage (31) Shakespeare and the Classical World (with an (2) Shakespearian Production index to Surveys 21–30) (3) The Man and the Writer (32) The Middle Comedies (4) Interpretation (33) King Lear (5) Textual Criticism (34) Characterization in Shakespeare (6) The Histories (35) Shakespeare in the Nineteenth Century (7) Style and Language (36) Shakespeare in the Twentieth Century (8) The Comedies (37) Shakespeare’s Earlier Comedies (9) Hamlet (38) Shakespeare and History (10) The Roman Plays (39) Shakespeare on Film and Television (11) The Last Plays (with an index (40) Current Approaches to Shakespeare through to Surveys 1–10) Language, Text and Theatre (12) The Elizabethan Theatre (41) Shakespearian Stages and Staging (with an (13) King Lear index to Surveys 31–40) (14) Shakespeare and his Contemporaries (42) Shakespeare and the Elizabethans (15) The Poems and Music -

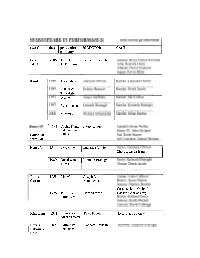

SHAKESPEARE in PERFORMANCE Some Screen Productions

SHAKESPEARE IN PERFORMANCE some screen productions PLAY date production DIRECTOR CAST company As You 2006 BBC Films / Kenneth Branagh Rosalind: Bryce Dallas Howard Like It HBO Films Celia: Romola Gerai Orlando: David Oyelewo Jaques: Kevin Kline Hamlet 1948 Two Cities Laurence Olivier Hamlet: Laurence Olivier 1980 BBC TVI Rodney Bennett Hamlet: Derek Jacobi Time-Life 1991 Warner Franco ~effirelli Hamlet: Mel Gibson 1997 Renaissance Kenneth Branagh Hamlet: Kenneth Branagh 2000 Miramax Michael Almereyda Hamlet: Ethan Hawke 1965 Alpine Films, Orson Welles Falstaff: Orson Welles Intemacional Henry IV: John Gielgud Chimes at Films Hal: Keith Baxter Midni~ht Doll Tearsheet: Jeanne Moreau Henry V 1944 Two Cities Laurence Olivier Henry: Laurence Olivier Chorus: Leslie Banks 1989 Renaissance Kenneth Branagh Henry: Kenneth Branagh Films Chorus: Derek Jacobi Julius 1953 MGM Joseph L Caesar: Louis Calhern Caesar Manluewicz Brutus: James Mason Antony: Marlon Brando ~assiis:John Gielgud 1978 BBC TV I Herbert Wise Caesar: Charles Gray Time-Life Brutus: kchard ~asco Antony: Keith Michell Cassius: David Collings King Lear 1971 Filmways I Peter Brook Lear: Paul Scofield AtheneILatenla Love's 2000 Miramax Kenneth Branagh Berowne: Kenneth Branagh Labour's and others Lost Macbeth 1948 Republic Orson Welles Macbeth: Orson Welles Lady Macbeth: Jeanette Nolan 1971 Playboy / Roman Polanslu Macbe th: Jon Finch Columbia Lady Macbeth: Francesca Annis 1998 Granada TV 1 Michael Bogdanov Macbeth: Sean Pertwee Channel 4 TV Lady Macbeth: Greta Scacchi 2000 RSC/ Gregory -

Diablotexto Digital (2018), 3, 43-74 43 Doi: 10.7203/Diablotexto.3.13015

The Tempest de William Shakespeare, dirigida por Gregory Doran (Royal Shakespeare Company, 2016-2017). Dialéctica entre tecnología virtual y corporalidad William Shakespeare´s The Tempest, Directed by Gregory Doran (Royal Shakespeare Company, 2016-2017). Dialectics between Virtual Technology and Corporality VÍCTOR HUERTAS MARTÍN SHAKESPEARE INSTITUTE (UNIVERSIDAD DE BIRMINGHAM) Resumen: Este artículo estudia la dialéctica que se da entre los cuerpos de los actores y la tecnología virtual en la producción de The Tempest de Gregory Doran (2016-2017). Dicha dialéctica será observada desde una óptica marxista – principalmente a partir del trabajo de Silvia Federici– y desde la crítica textual y escénica del texto de Shakespeare. Aspectos como la tecnología y el cuerpo serán de importancia para mi trabajo. Particularmente me centraré en el cuerpo como materia sometida al castigo corporal y a su instrumentalización en la película. También trabajaré a partir de la teorización de Gabriella Giannachi sobre el teatro virtual como herramienta de debate estético, político y ético en un entorno hipertextual. Estudiaré las interacciones entre los cuerpos y la tecnología en el espacio escénico del Royal Shakespeare Theatre y cómo dicha interrelación se traslada a la pantalla durante la emisión del espectáculo a través del live cinema. Palabras clave: Cuerpo, virtualidad, realidad; interacción; hipertexto; hipersuperficie Abstract: This article studies the dialectics between the actors’ bodies and virtual technology in a production of Gregory Doran’s The Tempest (2016-2017). Such dialectics will be observed from a Marxist lens – mainly through Silvia Federici’s work – and stage and textual criticism on Shakespeare’s play. Different aspects of technology and the body will be important for my work. -

King Lear Teacher Pack 2016

- 1 - Registered charity no. 212481 © Royal Shakespeare Company ABOUT THIS PACK This pack supports the RSC’s 2016 production of King Lear, directed by RSC Artistic Director Gregory Doran. The production opened on 17 August 2016 at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon. The activities provided are specifically designed to support KS3-4 students attending the performance and studying King Lear in school. These symbols are used throughout the pack: CONTENTS READ Notes from the production, About this Pack Page 2 background info or extracts Exploring the Story Page 3 ACTIVITY Dividing a Kingdom Page 4 A practical or open space activity Lear the King Page 5 WRITE Deception and Disguise Page 7 A classroom writing or discussion activity Resources Page 10 LINKS Useful web addresses and research tasks About the Production The 2016 production of King Lear, directed by Gregory Doran, responds very much to the idea of how this play relates to us ‘now’. Originally written by Shakespeare just after James I’s failed attempts to unify England and Scotland in 1606, the play was extremely current and this production aimed to replicate that. In the wake of the EU referendum the concept of a Kingdom divided and the fall out of those divisions for those who once held power felt just as strong as it would have done for Shakespeare. Designed by Niki Turner, the stage contains a box across the back which fills with smoke or fog and becomes slowly more hazy in the second half of the play as Lear loses increasingly more control. -

A Supporter of The

SUPPORTERS NEWS NOVEMBER 2015 2016 A PROUD YEAR TO BE A SUPPORTER OF THE RSC “I think we are going to be very proud of the reopening of The Other Place and the Swan Wing, when they open to the public next year”. On a recent visit to our two building projects I was amazed by the progress being made and wanted to share with our Supporters the excitement of the work taking place. The two workplaces have completely different energies, each one appropriate to the project. The beehive at TOP hums with noise as dozens of workmen busy themselves, tearing holes for new windows in the outside walls, or punching holes for roof lights in the ceiling. The innovative recycling efforts, and the industrious repurposing of the old rusty box that was the Courtyard Theatre, is zooming towards its conclusion. Meanwhile the work process at the Swan Wing is altogether quieter, and more intensely detailed, focused as it is on the challenges of restoring the fabric of a building which has stood by the Avon for nearly 135 years. The Swan Theatre Photo by Stewart Hemley The Swan Wing masonry has all been cleared in a careful sequence, using differently techniques and has revealed again the three terracotta plaques that grace the front of the Swan. The oriel bay window which usually over looks Weston square, now reveals fairy sculptures that peer beneath the window. A perky imp sheltering under a large anemone, and a demonic little goblin sits cross legged in a corner stretching his bat wings. All over the exterior of the building, piece in repairs, mortar repairs, discreet pinning and lime consolidation have all been undertaken to restore the fragile carved and plain stone surfaces. -

A Performance Study of William Shakespeare's Macbeth

Centre for Languages and Literature English Studies Nuances and Complexities: A Performance Study of William Shakespeare’s Macbeth Diana Iuga ENGK01 Degree project in English Literature Spring 2018 Centre for Languages and Literature Lund University Supervisor: Kiki Lindell Abstract Shakespeare’s play-texts have been subject to both performance and textual studies. However, due to the many possible elements of analysis in performance studies, there is still a lot left to cover in this line of research. This dissertation aims to add to the corpus of performance studies by analysing Macbeth and Lady Macbeth in four seminal, recorded productions of Shakespeare’s Macbeth. I argue that a combination of textual and performance studies, combined with attention to actors’ methods of working, can provide a deeper understanding of the personalities of Macbeth and Lady Macbeth, of their motives for committing murder, and of the changes they undergo throughout the play. The essay is divided into four sections, which cover different aspects of the two spouses in performance. The dissertation shows how textual analysis can strengthen and inform performance theories, and how studying the work by actors can deepen our understanding of the characters, as well as the play. 2 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 1 The Child, Backstory, and Motive ............................................................................................ -

By the Royal Shakespeare Company

Richard II (dir. Gregory Doran) by the Royal Shakespeare Company by Kevin Quarmby. Written on 2014-01-01. First published in the ISE Chronicle. For the production: Richard II (2013, Royal Shakespeare Company, UK). A coffin draped in black rests ominously centre stage, a black stool by its side. Lying in state, the unseen body of the Duke of Gloucester silently prologues a murderous heritage for the unfolding drama. Behind the coffin in trompe l'oeil verisimilitude, the vaulted nave of Westminster Abbey recedes like an architectural ghost into the far distance. Stage right and stage left, steel platforms offer staired entrances and exits. A woman, dressed in black, is escorted to the coffin. In obvious despair, she drapes herself over the casket as a trio of Figure 1: David Tennant as Richard II, photograph by Kwame Lestrade. Scene. University of Victoria. First published in the ISE Chronicle 2008-2015 19 DOI: 10.18357/scene00201418507 Royal Shakespeare Company – Richard II Kevin Quarmby sopranos chant medieval choral music, their voices hanging in the air long after notes have left their lips. We are in medieval England. All is grey and black and sombre. With none of the trappings of anachronistic merriness or nostalgic glee, this medieval England is a dark and dangerous site of politics, whose intrigue is punctuated with internecine feuding and sycophantic self-interest. This is the Royal Shakespeare Company’s production of Richard II. Despite the sombreness of the funerary occasion, the opening quarrel between the belligerent Bolingbroke and Thomas Mowbray preludes the comical gauntlet throwing one-upmanship of later scenes.