Redalyc.Rupert Goold's Macbeth (2010): Surveillance Society And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A TASTE of SHAKESPEARE: MACBETH a 52 Minute Video Available for Purchase Or Rental from Bullfrog Films

A TASTE OF SHAKESPEARE MACBETH Produced by Eugenia Educational Foundation Teacher’s Guide The video with Teacher’s Guide A TASTE OF SHAKESPEARE: MACBETH a 52 minute video available for purchase or rental from Bullfrog Films Produced in Association with BRAVO! Canada: a division of CHUM Limited Produced with the Participation of the Canadian Independent Film & Video Fund; with the Assistance of The Department of Canadian Heritage Acknowledgements: We gratefully acknowledge the support of The Ontario Trillium Foundation: an agency of the Ministry of Culture The Catherine & Maxwell Meighen Foundation The Norman & Margaret Jewison Foundation George Lunan Foundation J.P. Bickell Foundation Sir Joseph Flavelle Foundation ©2003 Eugenia Educational Foundation A Taste of Shakespeare: Macbeth Program Description A Taste of Shakespeare is a series of thought-provoking videotapes of Shakespeare plays, in which actors play the great scenes in the language of 16th and 17th century England, but comment on the action in the English of today. Each video is under an hour in length and is designed to introduce the play to students in high school and college. The teacher’s guide that comes with each video gives – among other things – a brief analysis of the play, topics for discussion or essays, and a short list of recom- mended reading. Production Notes At the beginning and end of this blood- soaked tragic play Macbeth fights bravely: loyal to his King and true to himself. (It takes nothing away from his valour that in the final battle King and self are one.) But in between the first battle and the last Macbeth betrays and destroys King, country, and whatever is good in his own nature. -

The Representation, Interpretation and Staging of Magic in Renaissance Plays from the Sixteenth Century Onwards

Ghent University Faculty of Arts and Philosophy The representation, interpretation and staging of magic in Renaissance plays from the sixteenth century onwards. A case study of William Shakespeare’s The Tempest, Macbeth and Cristopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus. Supervisor: Paper submitted in partial Professor Doctor fulfilment of the requirements for Sandro Jung the degree of “Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde: English-Spanish” by Tine Dekeyser August 2014 Word count: 27334 Dekeyser i Acknowledgments First of all, I would like to thank my supervisor, Professor Doctor Sandro Jung, for granting me the opportunity to continue working on the same topic of my BA-dissertation and for guiding me towards a more profound investigation of magic and the Renaissance society. Also, I want to thank Professor Jung for reading the many versions of this dissertation and for providing a lot of helpful suggestions throughout the year. Secondly, I would like to thank The British Museum for giving me permission to use their highly detailed engravings, without which this dissertation would not exist. Thirdly, I would like to thank my boyfriend and my mother for supporting me, listening to my dilemmas and calming me down when stress got the better of me. Also, I want to thank my boyfriend for helping me track down the movies I needed for my analyses. Dekeyser ii Table of Contents Acknowledgments ....................................................................................................................... i List of Illustrations ................................................................................................................... -

Macbeth Act by Act Study

GCSE ENGLISH LITERATURE MACBETH NAME:_____________________________________ LIT AO1, AO2, AO3 Act One Scene One The three witches meet in a storm and decide when they will meet up again. AO1: What does the weather suggest to the audience about these characters? _______________________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________________ AO2: Why are the lines below important? What do they establish about this play? Fair is foul, and foul is fair: Hover through the fog and filthy air. (from BBC Bitesize): In Shakespeare’s time people believed in witches. They were people who had made a pact with the Devil in exchange for supernatural powers. If your cow was ill, it was easy to decide it had been cursed. If there was plague in your village, it was because of a witch. If the beans didn’t grow, it was because of a witch. Witches might have a familiar – a pet, or a toad, or a bird – which was supposed to be a demon advisor. People accused of being witches tended to be old, poor, single women. It is at this time that the idea of witches riding around on broomsticks (a common household implement in Elizabethan England) becomes popular. King James I became king in 1603. He was particularly superstitious about witches and even wrote a book on the subject. Shakespeare wrote Macbeth -

Rory Kinnear

RORY KINNEAR Film: Peterloo Henry Hunt Mike Leigh Peterloo Ltd Watership Down Cowslip Noam Murro 42 iBoy Ellman Adam Randall Wigwam Films Spectre Bill Tanner Sam Mendes EON Productions Trespass Against Us Loveage Adam Smith Potboiler Productions Man Up Sean Ben Palmer Big Talk Productions The Imitation Game Det Robert Nock Morten Tydlem Black Bear Pictures Cuban Fury Gary James Griffiths Big Talk Productions Limited Skyfall Bill Tanner Sam Mendes Eon Productions Broken* Bob Oswald Rufus Norris Cuba Pictures Wild Target Gerry Jonathan Lynne Magic Light Quantum Of Solace Bill Tanner Marc Forster Eon Productions Television: Guerrilla Ch Insp Nic Pence John Ridley & Sam Miller Showtime Quacks Robert Andy De Emmony Lucky Giant The Casual Vacancy Barry Fairbrother Jonny Campbell B B C Penny Dreadful (Three Series) Frankenstein's Creature Juan Antonio Bayona Neal Street Productions Lucan Lord Lucan Adrian Shergold I T V Studios Ltd Count Arthur Strong 1 + 2 Mike Graham Linehan Retort Southcliffe David Sean Durkin Southcliffe Ltd The Hollow Crown Richard Ii Various Neal Street Productions Loving Miss Hatto Young Barrington Coupe Aisling Walsh L M H Film Production Ltd Richard Ii Bolingbroke Rupert Goold Neal Street Productions Black Mirror; National Anthem Michael Callow Otto Bathurst Zeppotron Edwin Drood Reverend Crisparkle Diarmuid Lawrence B B C T V Drama Lennon Naked Brian Epstein Ed Coulthard Blast Films First Men Bedford Damon Thomas Can Do Productions Vexed Dan Matt Lipsey Touchpaper T V Cranford (two Series) Septimus Hanbury Simon Curtis B B C Beautiful People Ross David Kerr B B C The Thick Of It Ed Armando Iannucci B B C Waking The Dead James Fisher Dan Reed B B C Ashes To Ashes Jeremy Hulse Ben Bolt Kudos For The Bbc Minder Willoughby Carl Nielson Freemantle Steptoe & Sons Alan Simpson Michael Samuels B B C Plus One (pilot) Rob Black Simon Delaney Kudos Messiah V Stewart Dean Harry Bradbeer Great Meadow Rory Kinnear 1 Markham Froggatt & Irwin Limited Registered Office: Millar Court, 43 Station Road, Kenilworth, Warwickshire CV8 1JD Registered in England N0. -

Three Eras, Two Men, One Value: Fides in Modern Performances of Shakespeare’S

Three Eras, Two Men, One Value: Fides in Modern Performances of Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra Depictions of Marc Antony and Caesar Augustus have changed dramatically between the first and twenty-first centuries, partially because of William Shakespeare’s seventeenth-century play Antony and Cleopatra. In 2006 and 2010, England’s Royal Shakespeare Company staged vastly different interpretations of this classically influenced Shakespearean text. How do the modern performances rework ancient views of Antony and Augustus, particularly in light of the ancient Roman value fides (loyalty or good faith)? This paper answers that question by examining the intersections between Greco-Roman literary-historic narratives – as received in Shakespeare’s early modern play – and the two modern performances. The contemporary versions of Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra create contrasting constructions of Antony and Augustus by modernizing the characters and/or their worlds. The 2006 rendition (directed by Gregory Doran) presents an explosive but weak-willed Antony (Sir Patrick Stewart) and a prudish yet petulant Augustus (John Hopkins). On the other hand, the 2010 adaptation (directed by Michael Boyd) shows a hotheaded and frank Antony (Darrell D’Silva) who struggles against a cold and manipulative Augustus (John Mackay). Both performances reveal the complexity of these ancient figures as the men engage with and evaluate claims upon their familial, societal, and personal fides. Representations of Antony and Augustus necessarily involve fides, though classical accounts do not always feature this term. As military and political leaders, both men led lives filled with decisions about loyalty, specifically what deserved it and in what degree. The modern dramatizations further underscore fides in their portrayals of Antony and Augustus. -

Macbeth on Three Levels Wrap Around a Deep Thrust Stage—With Only Nine Rows Dramatis Personae 14 Separating the Farthest Seat from the Stage

Weird Sister, rendering by Mieka Van Der Ploeg, 2019 Table of Contents Barbara Gaines Preface 1 Artistic Director Art That Lives 2 Carl and Marilynn Thoma Bard’s Bio 3 Endowed Chair The First Folio 3 Shakespeare’s England 5 Criss Henderson The English Renaissance Theater 6 Executive Director Courtyard-Style Theater 7 Chicago Shakespeare Theater is Chicago’s professional theater A Brief History of Touring Shakespeare 9 Timeline 12 dedicated to the works of William Shakespeare. Founded as Shakespeare Repertory in 1986, the company moved to its seven-story home on Navy Pier in 1999. In its Elizabethan-style Courtyard Theater, 500 seats Shakespeare's Macbeth on three levels wrap around a deep thrust stage—with only nine rows Dramatis Personae 14 separating the farthest seat from the stage. Chicago Shakespeare also The Story 15 features a flexible 180-seat black box studio theater, a Teacher Resource Act by Act Synopsis 15 Center, and a Shakespeare specialty bookstall. In 2017, a new, innovative S omething Borrowed, Something New: performance venue, The Yard at Chicago Shakespeare, expanded CST's Shakespeare’s Sources 18 campus to include three theaters. The year-round, flexible venue can 1606 and All That 19 be configured in a variety of shapes and sizes with audience capacities Shakespeare, Tragedy, and Us 21 ranging from 150 to 850, defining the audience-artist relationship to best serve each production. Now in its thirty-second season, the Theater has Scholars' Perspectives produced nearly the entire Shakespeare canon: All’s Well That Ends -

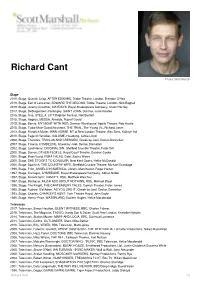

Richard Cant

Richard Cant Photo: Wolf Marloh Stage 2019, Stage, Quentin Crisp, AFTER EDWARD, Globe Theatre, London, Brendan O'Hea 2019, Stage, Earl of Lancaster, EDWARD THE SECOND, Globe Theatre, London, Nick Bagnall 2018, Stage, Jeremy Crowther, MAYDAYS, Royal Shakespeare Company, Owen Horsley 2017, Stage, DeStogumber/ Poulengey, SAINT JOAN, Donmar, Josie Rourke 2016, Stage, One, STELLA, LIFT/Brighton Festival, Neil Bartlett 2015, Stage, Aegeus, MEDEA, Almeida, Rupert Goold 2015, Stage, Bernie, MY NIGHT WITH REG, Donmar Warehouse/ Apollo Theatre, Rob Hastie 2015, Stage, Tudor/Male Guard/Assistant, THE TRIAL, The Young Vic, Richard Jones 2013, Stage, Friedrich Muller, WAR HORSE, NT at New London Theatre, Alex Sims, Kathryn Ind 2010, Stage, Page of Herodias, SALOME, Headlong, Jamie Lloyd 2008, Stage, Thersites, TROILUS AND CRESSIDA, Cheek by Jowl, Declan Donnellan 2007, Stage, Pisanio, CYMBELINE, Cheek by Jowl, Declan Donnellan 2002, Stage, Lord Henry, ORIGINAL SIN, Sheffield Crucible Theatre, Peter Gill 2000, Stage, Darren, OTHER PEOPLE, Royal Court Theatre, Dominic Cooke 2000, Stage, Brian/Javid, PERA PALAS, Gate, Sacha Wares 2000, Stage, SHE STOOPS TO CONQUER, New Kent Opera, Hettie McDonald 2000, Stage, Sparkish, THE COUNTRY WIFE, Sheffield Crucible Theatre, Michael Grandage 1999, Stage, Prior, ANGELS IN AMERICA, Library, Manchester, Roger Haines 1997, Stage, Arviragus, CYMBELINE, Royal Shakespeare Company, Adrian Noble 1997, Stage, Rosencrantz, HAMLET, RSC, Matthew Warchus 1997, Stage, Balthasar, MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING, RSC, Michael Boyd 1996, Stage, -

From 'Scottish' Play to Japanese Film: Kurosawa's Throne of Blood

arts Article From ‘Scottish’ Play to Japanese Film: Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood Dolores P. Martinez Emeritus Reader, SOAS, University of London, London WC1H 0XG, UK; [email protected] Received: 16 May 2018; Accepted: 6 September 2018; Published: 10 September 2018 Abstract: Shakespeare’s plays have become the subject of filmic remakes, as well as the source for others’ plot lines. This transfer of Shakespeare’s plays to film presents a challenge to filmmakers’ auterial ingenuity: Is a film director more challenged when producing a Shakespearean play than the stage director? Does having auterial ingenuity imply that the film-maker is somehow freer than the director of a play to change a Shakespearean text? Does this allow for the language of the plays to be changed—not just translated from English to Japanese, for example, but to be updated, edited, abridged, ignored for a large part? For some scholars, this last is more expropriation than pure Shakespeare on screen and under this category we might find Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood (Kumonosu-jo¯ 1957), the subject of this essay. Here, I explore how this difficult tale was translated into a Japanese context, a society mistakenly assumed to be free of Christian notions of guilt, through the transcultural move of referring to Noh theatre, aligning the story with these Buddhist morality plays. In this manner Kurosawa found a point of commonality between Japan and the West when it came to stories of violence, guilt, and the problem of redemption. Keywords: Shakespeare; Kurosawa; Macbeth; films; translation; transcultural; Noh; tragedy; fate; guilt 1. -

Macbeth in World Cinema: Selected Film and Tv Adaptations

International Journal of English and Literature (IJEL) ISSN 2249-6912 Vol. 3, Issue 1, Mar 2013, 179-188 © TJPRC Pvt. Ltd. MACBETH IN WORLD CINEMA: SELECTED FILM AND TV ADAPTATIONS RITU MOHAN 1 & MAHESH KUMAR ARORA 2 1Ph.D. Scholar, Department of Management and Humanities, Sant Longowal Institute of Engineering and Technology, Longowal, Punjab, India 2Associate Professor, Department of Management and Humanities, Sant Longowal Institute of Engineering and Technology, Longowal, Punjab, India ABSTRACT In the rich history of Shakespearean translation/transcreation/appropriation in world, Macbeth occupies an important place. Macbeth has found a long and productive life on Celluloid. The themes of this Bard’s play work in almost any genre, in any decade of any generation, and will continue to find their home on stage, in film, literature, and beyond. Macbeth can well be said to be one of Shakespeare’s most performed play and has enchanted theatre personalities and film makers. Much like other Shakespearean works, it holds within itself the most valuable quality of timelessness and volatility because of which the play can be reproduced in any regional background and also in any period of time. More than the localization of plot and character, it is in the cinematic visualization of Shakespeare’s imagery that a creative coalescence of the Shakespearean, along with the ‘local’ occurs. The present paper seeks to offer some notable (it is too difficult to document and discuss all) adaptations of Macbeth . The focus would be to provide introductory information- name of the film, country, language, year of release, the director, star-cast and the critical reception of the adaptation among audiences. -

Lady Macbeth, the Ill-Fated Queen

LADY MACBETH, THE ILL-FATED QUEEN: EXPLORING SHAKESPEAREAN THEMES OF AMBITION, SEXUALITY, WITCHCRAFT, PATRILINEAGE, AND MATRICIDE IN VOCAL SETTINGS OF VERDI, SHOSTAKOVICH, AND PASATIERI BY 2015 Andrea Lynn Garritano ANDREA LYNN GARRITANO Submitted to the graduate degree program in Music and the Graduate Faculty of The University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson, Dr. Roberta Freund Schwartz ________________________________ Prof. Joyce Castle ________________________________ Dr. John Stephens ________________________________ Dr. Kip Haaheim ________________________________ Dr. Martin Bergee Date Defended: December 19, 2014 ii The Dissertation Committee for ANDREA LYNN GARRITANO Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: LADY MACBETH, THE ILL-FATED QUEEN: EXPLORING SHAKESPEAREAN THEMES OF AMBITION, SEXUALITY, WITCHCRAFT, PATRILINEAGE, AND MATRICIDE IN VOCAL SETTINGS OF VERDI, SHOSTAKOVICH, AND PASATIERI ______________________________ Chairperson, Dr. Roberta Freund Schwartz Date approved: January 31, 2015 iii Abstract This exploration of three vocal portrayals of Shakespeare’s Lady Macbeth investigates the transference of themes associated with the character is intended as a study guide for the singer preparing these roles. The earliest version of the character occurs in the setting of Verdi’s Macbeth, the second is the archetypical setting of Lady Macbeth found in the character Katerina Ismailova from -

Julius Caesar

BAM 2013 Winter/Spring Season Brooklyn Academy of Music BAM, the Royal Shakespeare Company, Alan H. Fishman, and The Ohio State University present Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Julius Vice Chairman of the Board Karen Brooks Hopkins, President Joseph V. Melillo, Caesar Executive Producer Royal Shakespeare Company By William Shakespeare BAM Harvey Theater Apr 10—13, 16—20 & 23—27 at 7:30pm Apr 13, 20 & 27 at 2pm; Apr 14, 21 & 28 at 3pm Approximate running time: two hours and 40 minutes, including one intermission Directed by Gregory Doran Designed by Michael Vale Lighting designed by Vince Herbert Music by Akintayo Akinbode Sound designed by Jonathan Ruddick BAM 2013 Winter/Spring Season sponsor: Movement by Diane Alison-Mitchell Fights by Kev McCurdy Associate director Gbolahan Obisesan BAM 2013 Theater Sponsor Julius Caesar was made possible by a generous gift from Frederick Iseman The first performance of this production took place on May 28, 2012 at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Leadership support provided by The Peter Jay Stratford-upon-Avon. Sharp Foundation, Betsy & Ed Cohen / Arete Foundation, and the Hutchins Family Foundation The Royal Shakespeare Company in America is Major support for theater at BAM: presented in collaboration with The Ohio State University. The Corinthian Foundation The Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation Stephanie & Timothy Ingrassia Donald R. Mullen, Jr. The Fan Fox & Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, Inc. Post-Show Talk: Members of the Royal Shakespeare Company The Morris and Alma Schapiro Fund Friday, April 26. Free to same day ticket holders The SHS Foundation The Shubert Foundation, Inc. -

Chicago Shakespeare in the Parks Tour Into Their Neighborhoods Across the Far North, West, and South Sides of the City

ANNOUNCING OUR 2018/2019 SEASON —The Merry Wives of Windsor Explosive, Pulitzer Prize-winning drama. Shakespeare’s tale of magic and mayhem—reimagined. The “76-trombone,” Tony-winning musical The Music Man. And so much more! 5-play Memberships start at just $100. We’re Only Alive For A Short Amount Of Time | How To Catch Creation | Sweat The Winter’s Tale | The Music Man | Lady In Denmark | Twilight Bowl | Lottery Day GoodmanTheatre.org/1819Season 312.443.3800 2018/2019 Season Sponsors MACBETH Contents Chicago Shakespeare Theater 800 E. Grand on Navy Pier On the Boards 10 Chicago, Illinois 60611 A selection of notable CST events, plays, and players 312.595.5600 www.chicagoshakes.com Conversation with the Directors 14 ©2018 Chicago Shakespeare Theater All rights reserved. Cast 23 ARTISTIC DIRECTOR CARL AND MARILYNN THOMA ENDOWED CHAIR: Barbara Gaines EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Playgoer's Guide 24 Criss Henderson PICTURED: Ian Merrill Peakes Profiles 26 and Chaon Cross COVER PHOTO BY: Jeff Sciortino ABOVE PHOTO BY: joe mazza A Scholar’s Perspective 40 The Basic Program of Liberal Education for Adults is a rigorous, non- Part of the John W. and Jeanne M. Rowe credit liberal arts program that draws on the strong Socratic tradition Inquiry and Exploration Series at the University of Chicago. There are no tests, papers, or grades; you will instead delve into the foundations of Western political and social thought through instructor-led discussions at our downtown campus and online. EXPLORE MORE AT: graham.uchicago.edu/basicprogram www.chicagoshakes.com 5 Welcome DEAR FRIENDS, When we first imagined The Yard at Chicago Shakespeare and the artistic capacity inherent in its flexible design, we hoped that this new venue would invite artists to dream big as they approached Shakespeare’s work.