Theatrical Self-Reflexivity in Gregory Doran's Hamlet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Antique Spoon Collectors' Magazine

The Antique Spoon Collectors’ Magazine …The Finial… ISSN 1742-156X Volume 25/01 Where Sold £8.50 September/October 2014 ‘The Silver Spoon Club’ OF GREAT BRITAIN ___________________________________________________________________________ 5 Cecil Court, Covent Garden, London. WC2N 4EZ V.A.T. No. 658 1470 21 Tel: 020 7240 1766 www.bexfield.co.uk/thefinial [email protected] Hon. President: Anthony Dove F.S.A. Editor: Daniel Bexfield Volume 25/01 September/October 2014 CONTENTS Introduction 3 Advertisement – Dudley Antique Silver 3 The influence of the reformation of London hallmarking by David Mckinley 4 New Publication – Exeter & West Country Silver 1700-1900 by M. Harrison 5 Advertisement – Lawrences Auctioneers 6 The Ayr spoon request by Kirkpatrick Dobie 7 The broad arrow mark by Luke Schrager 8 Advertisement – Christie’s 10 Feedback 11 London Assay Office - Hallmarking information day 13 Advertisement – Lyon & Turnbull 13 Review – Lyon & Turnbull sale – 13th August 2014 by Mr M 14 Review – Fellows Sale, Birmingham by Emma Cann 16 Results for the Club Postal Auction – 28th August 17 The Club Postal Auction 18 The next postal auction 43 Postal auction information 43 -o-o-o-o-o-o- COVER Left: Queen Anne Britannia Silver Rattail Dognose Spoon Made by William Petley London 1702 Right: William III Britannia Silver Rattail Dognose Spoon Made by John Cove of Bristol London 1698 See: The Postal Auction, page 35, Lots 155 & 156 -o-o-o-o-o-o- Yearly Subscription to The Finial UK - £39.00; Europe - £43.00; N. America - £47.00; Australia - £49.00 In PDF format by email - £30.00 (with hardcopy £15.00) -o-o-o-o-o-o- The Finial is the illustrated journal of The Silver Spoon Club of Great Britain Published by Daniel Bexfield 5 Cecil Court, Covent Garden, London, WC2N 4EZ. -

Three Eras, Two Men, One Value: Fides in Modern Performances of Shakespeare’S

Three Eras, Two Men, One Value: Fides in Modern Performances of Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra Depictions of Marc Antony and Caesar Augustus have changed dramatically between the first and twenty-first centuries, partially because of William Shakespeare’s seventeenth-century play Antony and Cleopatra. In 2006 and 2010, England’s Royal Shakespeare Company staged vastly different interpretations of this classically influenced Shakespearean text. How do the modern performances rework ancient views of Antony and Augustus, particularly in light of the ancient Roman value fides (loyalty or good faith)? This paper answers that question by examining the intersections between Greco-Roman literary-historic narratives – as received in Shakespeare’s early modern play – and the two modern performances. The contemporary versions of Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra create contrasting constructions of Antony and Augustus by modernizing the characters and/or their worlds. The 2006 rendition (directed by Gregory Doran) presents an explosive but weak-willed Antony (Sir Patrick Stewart) and a prudish yet petulant Augustus (John Hopkins). On the other hand, the 2010 adaptation (directed by Michael Boyd) shows a hotheaded and frank Antony (Darrell D’Silva) who struggles against a cold and manipulative Augustus (John Mackay). Both performances reveal the complexity of these ancient figures as the men engage with and evaluate claims upon their familial, societal, and personal fides. Representations of Antony and Augustus necessarily involve fides, though classical accounts do not always feature this term. As military and political leaders, both men led lives filled with decisions about loyalty, specifically what deserved it and in what degree. The modern dramatizations further underscore fides in their portrayals of Antony and Augustus. -

David Yelland Photo: Catherine Shakespeare Lane

Paddock Suite, The Courtyard, 55 Charterhouse Street, London, EC1M 6HA p: + 44 (0) 20 73360351 e: [email protected] Phone: + 44 (0) 20 73360351 Email: [email protected] David Yelland Photo: Catherine Shakespeare Lane Eastern European, Scandinavian, Location: London Appearance: White Height: 5'11" (180cm) Other: Equity Weight: 13st. 6lb. (85kg) Eye Colour: Blue Playing Age: 51 - 65 years Hair Length: Mid Length Stage Stage, Cardinal Von Galen, All Our Children, Jermyn Street Theatre, Stephen Unwin Stage, Antigonus, The Winter's Tale, Globe Theatre, Michael Longhurst Stage, Lord Clifford Allen, Taken At Midnight, Chichester Festival Theatre & Haymarket Theatre, Jonathan Church Stage, Earl of Caversham, An Ideal Husband, Gate Theatre, Ethan McSweeney Stage, Sir George Crofts, Mrs Warren's Profession, Gate Theatre, Dublin, Patrick Mason Stage, Selwyn Lloyd, A Marvellous Year For Plums, Chichester Festival Theatre, Philip Franks Stage, Serebryakov, Uncle Vanya, The Print Room, Lucy Bailey Stage, King Henry, Henry IV Parts 1&2, Theatre Royal Bath & Tour, Sir Peter Hall Stage, Anthony Blunt, Single Spies, The Watermill, Jamie Glover Stage, Crofts, Mrs Warren's Profession, Theatre Royal Bath & West End, Michael Rudman Stage, President of the Court, For King & Country, Matthew Byam shaw, Tristram Powell Stage, Clive, The Circle, Chichester Festival Theatre, Jonathan Church Stage, Ralph Nickleby, Nicholas Nickleby, Chichester Festival Theatre,Gielgud , and Toronto, Philip Franks, Jonathan Church Stage, Wilfred Cedar, For Services Rendered, The Watermill -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

Early Puritanism in the Southern and Island Colonies

Early Puritanism in the Southern and Island Colonies BY BABETTE M. LEVY Preface NE of the pleasant by-products of doing research O work is the realization of how generously help has been given when it was needed. The author owes much to many people who proved their interest in this attempt to see America's past a little more clearly. The Institute of Early American History and Culture gave two grants that enabled me to devote a sabbatical leave and a summer to direct searching of colony and church records. Librarians and archivists have been cooperative beyond the call of regular duty. Not a few scholars have read the study in whole or part to give me the benefit of their knowledge and judgment. I must mention among them Professor Josephine W, Bennett of the Hunter College English Department; Miss Madge McLain, formerly of the Hunter College Classics Department; the late Dr. William W. Rockwell, Librarian Emeritus of Union Theological Seminary, whose vast scholarship and his willingness to share it will remain with all who knew him as long as they have memories; Professor Matthew Spinka of the Hartford Theological Sem- inary; and my mother, who did not allow illness to keep her from listening attentively and critically as I read to her chapter after chapter. All students who are interested 7O AMERICAN ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY in problems concerning the early churches along the Atlantic seaboard and the occupants of their pulpits are indebted to the labors of Dr. Frederick Lewis Weis and his invaluable compendiums on the clergymen and parishes of the various colonies. -

Julius Caesar

BAM 2013 Winter/Spring Season Brooklyn Academy of Music BAM, the Royal Shakespeare Company, Alan H. Fishman, and The Ohio State University present Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Julius Vice Chairman of the Board Karen Brooks Hopkins, President Joseph V. Melillo, Caesar Executive Producer Royal Shakespeare Company By William Shakespeare BAM Harvey Theater Apr 10—13, 16—20 & 23—27 at 7:30pm Apr 13, 20 & 27 at 2pm; Apr 14, 21 & 28 at 3pm Approximate running time: two hours and 40 minutes, including one intermission Directed by Gregory Doran Designed by Michael Vale Lighting designed by Vince Herbert Music by Akintayo Akinbode Sound designed by Jonathan Ruddick BAM 2013 Winter/Spring Season sponsor: Movement by Diane Alison-Mitchell Fights by Kev McCurdy Associate director Gbolahan Obisesan BAM 2013 Theater Sponsor Julius Caesar was made possible by a generous gift from Frederick Iseman The first performance of this production took place on May 28, 2012 at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Leadership support provided by The Peter Jay Stratford-upon-Avon. Sharp Foundation, Betsy & Ed Cohen / Arete Foundation, and the Hutchins Family Foundation The Royal Shakespeare Company in America is Major support for theater at BAM: presented in collaboration with The Ohio State University. The Corinthian Foundation The Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation Stephanie & Timothy Ingrassia Donald R. Mullen, Jr. The Fan Fox & Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, Inc. Post-Show Talk: Members of the Royal Shakespeare Company The Morris and Alma Schapiro Fund Friday, April 26. Free to same day ticket holders The SHS Foundation The Shubert Foundation, Inc. -

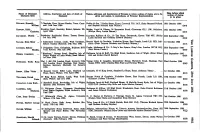

Name of Deceased

Name of Deceased Address, description and date of death of Names, addresses and descriptions of Persons to whom notices of claims are to be Date before which (Surname first) notices of claims Deceased given and names, in parentheses, of Personal Representatives to be given GILLMAN, Kenneth 7 Charlotte Close, Mount Hawke, Truro, Corn- Nalder & Son, 7 Pydar Street, Truro, Cornwall TR1 2AT. (John Bernard Pollock 10th October 1986 William. wall. 14th June 1986. and Stephen Richard John Wilcox.) (014) CHIDGEY, Edith Brockley Court, Brockley, Bristol, Spinster. 8th Madge, Lloyd & Gibson, 34 Brunswick Road, Gloucester GL1 1JW, Solicitors. 14th October 1986 Charlotte. April 1986. (Evelyn Mary Louisa Barnes.) (015) CALVERLEY, Phyllis Puddavine Residential Home, Tomes, Devon. Courtney Rallison & Co., 10 The Quay, Dartmouth, Devon TQ6 9PT. (Philip 26th September 1986 3rd July 1986. Leslie Rallison and Geoffrey Edward Bennett.) (016) NAYLOR, Eliza Mary ... 1 Sutherland Avenue, Leeds, West Yorkshire, Brooke North & Goodwin, Yorkshire House, East Parade, Leeds LSI 5SD, Soli- 1st October 1986 School Teacher (Retired). 24th May 1986. citors. (Peter Duncan Goodwin and Gordon Watson.) (017) COOMBES, Sydney 3 Ovingdean Close, Ovingdean, Brighton BN2 Cooke, Matheson & Co., 9 Gray's Inn Square, Gray's Inn, London WC1R 5JQ. 26th September 1986 Rhodes. 7AD, Retired. 14th July 1986. (Eric Edwin Cooke.) (018) WEEKS, Constance "Westbury," Queens Road, Shanklin, Isle of Robinson Jarvis & Rolf, 53A High Street, Sandown, Isle of Wight. (Peter Elliott 26th September 1986 Wight, Widow of Leslie Weeks, Bank Official. Gill and Robert David Baxter.) (019) 1st June 1986. i HANRAHAN, Emily Rose Flat 1, 469 Old London Road, formerly 51 SB Young Coles & Langdon, Queensbury House, Havelock Road, Hastings, East 22nd October 1986 Old London Road, Hastings, East Sussex, Sussex TN34 1DD. -

Some Thoughts Surrounding 2016Production of the Tempest

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by DSpace at Waseda University Some thoughts surrounding 2016 production of The Tempest UMEMIYA Yu The following note shows the result of an on going research on the play by William Shakespeare: The Tempest. The 2016 production at the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC), one of the leading theatre companies in England, demonstrated another innovative version of the play on their main stage in Stratford-upon-Avon, followed by its tour down to Barbican theatre in London in 2017. It did not include an extraordinary interpretation or unique casting pattern but demonstrated the extended development of technology available on stage. This note introduces the feature and the reception of the production in the latter half, with a brief summary of the play and a survey of the performance history of The Tempest in the first half. The story of The Tempest Compared to other plays by Shakespeare, The Tempest is a rare example that follows the classical idea of three unities of time, place and action, deriving from 1 Aristotle, then prescribed by Philip Sydney in Renaissance England . The similar 2 structure has already practiced in The Comedy of Errors in 1594 , but while this early comedy is often described as a simple farce, The Tempest contains various complications in terms of plots and theatrical possibilities. The story of The Tempest opens with a storm at sea, conjured by the magic of Prospero, the main character of the play. He is manipulating the tempest from the 一二七nearby island where he lives with his daughter, Miranda, and shares the land with two other fantastic creatures, Ariel and Caliban. -

Artsemerson: the World on Stage Announces Royal Shakespeare Company Live Returning with Two Films

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Ami Bennitt 617‐797‐8267, [email protected] ArtsEmerson: The World On Stage Announces Royal Shakespeare Company Live Returning With Two Films LOVE’S LABOUR’S LOST and LOVE’S LABOUR’S WON Emerson/Paramount Center’s Bright Family Screening Room March and April, 2015 [BOSTON, MA – February 17, 2015] ArtsEmerson: The World On Stage announces RSC Live returning with two film screenings: William Shakespeare’s Love’s Labour’s Lost (March 6‐8, 2015) and Love’s Labour’s Won also known as Much Ado About Nothing (April 24‐26, 2015) by the U.K.’s Royal Shakespeare Company. Screenings take place at the Emerson/Paramount Center’s Bright Family Screening Room (559 Washington Street in Boston’s historic theatre district). Tickets are $18 and may be purchased at ArtsEmerson.org or by calling 617.824.8400. Love’s Labour’s Lost Synopsis: Summer 1914. In order to dedicate themselves to a life of study, the King and his friends take an oath to avoid the company of women for three years. No sooner had they made their pledge than the Princess of France and her ladies‐in‐waiting arrived, presenting them with a severe test of resolve. Shakespeare’s sparkling comedy delights in championing and then unravelling an unrealistic vow, mischievously suggesting that the study of the opposite sex is in fact the highest of all academic endeavors. The merriment is curtailed only at the end of the play as the lovers agree to submit to a period apart, unaware that the world around them is about to be utterly transformed by a war to end all wars. -

Theatre Access

ACCESS MATTERS Welcome to our Winter 2017 Access Matters, where you can find out about our access provision and our forthcoming assisted performances. Old stories are so often the ones we return to again and again to make sense of the world around us. As our Rome collection of plays continues into autumn, we see how Shakespeare, his contemporaries and modern writers also seek inspiration in history and myth to fuel stories that still resonate in 2017. Rome Season Director, Angus Jackson, returns to the Royal Shakespeare Theatre with the last of Shakespeare’s Roman plays, Coriolanus. Sope Dirisu – a rising talent who originally emerged through our very own Open Stages programme – is an exciting Coriolanus. Another new voice emerges in the Swan Theatre: Kimberley Sykes, Associate Director on our Dream 16 tour makes her RSC directorial debut with Christopher Marlowe’s tragedy, Dido, Queen of Carthage. Our Swan Theatre season continues with a new adaptation of Robert Harris’ epic Cicero trilogy by Mike Poulton (Wolf Hall/Bring Up the Bodies). This thrilling political saga tells the story of the rise Communications Design by RSC Visual and fall of the great Roman orator, Cicero. Ovid was Shakespeare’s favourite poet and references to these classical stories litter his plays. We have lost our cultural familiarity with many of these and I feel passionate about reigniting our understanding of these wonderful fables. Over three weeks, eight events will explore Ovid’s stories from many angles. New voices resound around The Other Place once again with two Mischief Festivals. The first, in May, sees the return to the RSC of writer Tom Morton-Smith (Oppenheimer, 2015) and the co-writing debut of Matt Hartley and Kirsty Housley with a double bill of provocative short plays. -

Edward Bennett

Edward Bennett Showreel Agents Lucia Pallaris Assistant [email protected] Eleanor Kirby +44 (0) 20 3214 0909 [email protected] Roles Television Production Character Director Company SAVE ME TOO Max Owen Various Sky Atlantic COBRA (Series 2) Peter Mott Various Sky INDUSTRY Goldman Sachs Mary Nighy BBC/HBO MD COBRA (Series 1) Peter Mott Hans Herbots Sky PENNYWORTH Lord Longbrass Danny Cannon Warner Bros. POLDARK Prime Minister Pitt BBC VICTORIA SERIES 2 Trevelyan Jim Loach Mammoth Screen for ITV 1 MIRANDA Michael BBC THE PERFECTIONISTS Michael Tristram BBC Shapeero ABOVE SUSPICION - THE RED Charles Giles MacKinnon La Plante Productions/ITV DAHLIA Wickenham AFTER YOU'RE GONE Peter BBC SILENT WITNESS Gregory Kriss BBC United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Film Production Character Director Company THE LAUREATE Jonathan Cape William Nunez Bohemia Media BENEDICTION T E Lawrence Terence Davies EMU Films LOVE SONG Billy Scott Graham and Digital Theatre Steven Hoggart 55 STEPS Dr. Steven Booker Bille August Elsani Film LOVES LABOURS Berowne/Benedick Chris Luscombe RSC LOST/LOVE LABOURS WON JAMES BOND 'SKYFALL' Whitehall Assistant Sam Mendes Skyfall Productions WAR HORSE Cavalry Recruitment Stephen Speilberg Dreamworks Officer HAMLET Laertes Greg Doran RSC FRIENDS JUST UNITED Willis John Maxby Stage Production Character Director Company BREAKING THE CODE Alan Turing Christian Durham Salisbury Playhouse MACBETH Macduff Polly Findlay -

Shakespeare in South Africa: an Examination of Two Performances of Titus Andronicus in Apartheid and Post- Apartheid South Africa

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2017 Shakespeare in South Africa: An Examination of Two Performances of Titus Andronicus in Apartheid and Post- Apartheid South Africa Erin Elizabeth Whitaker University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Other English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Whitaker, Erin Elizabeth, "Shakespeare in South Africa: An Examination of Two Performances of Titus Andronicus in Apartheid and Post-Apartheid South Africa. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2017. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4911 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Erin Elizabeth Whitaker entitled "Shakespeare in South Africa: An Examination of Two Performances of Titus Andronicus in Apartheid and Post- Apartheid South Africa." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in English. Heather A. Hirschfeld, Major Professor We have read