Injunctive Relief and Civil Rico: After Scheidler V. National Organization for Women, Inc., Rico's Scope and Remedies Require Reevaluation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EFFICACY of ORGANIC WEED CONTROL METHODS Scott Snell, Natural Resources Specialist

FINAL STUDY REPORT (Cape May Plant Materials Center, Cape May Court House, NJ) EFFICACY OF ORGANIC WEED CONTROL METHODS Scott Snell, Natural Resources Specialist ABSTRACT Organic weed control methods have varying degrees of effectiveness and cover a broad range of costs financially and in time. Studies were conducted at the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service Cape May Plant Materials Center, Cape May Court House, New Jersey to examine the efficacy and costs of a variety of organic weed control methods: tillage, organic herbicide (acetic acid), flame treatment, solarization, and use of a smother cover crop. The smother cover and organic herbicide treatment plots displayed the least efficacy to control weeds with the average percent weed coverage of each method being over 97%. The organic herbicide plots also had the greatest financial costs and required the second most treatment time following the flame treatment plots. Although the flame treatment method was time consuming, it was effective resulting in an average of 12.14% weed coverage. Solarization required below average treatment time and resulted in an average of 49.22% weed coverage. The tillage method was found to be the most effective means of control and also had well below average financial costs and required slightly above average treatment time. INTRODUCTION The final results of the third biennial national Organic Farming Research Foundation’s (OFRF) survey found that organic producers rank weed control as one of the top problems negatively affecting their farms’ profitability (1999). Weed control options available for organic producers are far more limited than those of conventional production due to organic certification standards. -

Money Laundering

Money Laundering Alex Ferguson - Legal Adviser, Caribbean Criminal Asset Recovery Programme Objectives • History and background to money laundering; • The stages of money laundering; • Types of money laundering schemes; • Money Laundering Offences • Prosecutions types; • The predicate offences; • Current trends History The term money laundering is said to have its origins from the mafia’s ownership of Laundromats in the US in the 1920’s and 1930’s. Orgainised criminals were making so much money from extortion, prostitution, gambling and bootlegging, they needed to show a legitimate source of the money. One way in which they could do this was to purchase outwardly legitimate businesses and to mix their illicit earnings with the legitimate earnings from these businesses. Laundromats were chosen because they were cash businesses. Al Capone used this method in Chicago. Journalist Geoffrey Robinson regards the tale that money laundering came from this as a myth. He states: Money Laundering is called what it is because it perfectly describes what takes place – illegal or dirty money is put through a cycle of transactions, or washed, so that it comes out the other end as legal or clean money. In other words, the source of the illegally obtained funds is obscured through a succession of transfers and deals in order that those same funds can eventually be made to appear as legitimate income. Meyer Lansky Lansky was to become known as the Mobster’s accountant. He was determined that the same fate that came of Al Capone would not befall him and he set about finding ways to hide money. Through this determination he discovered the benefits of numbered Swiss bank accounts. -

Invasive Weeds of the Appalachian Region

$10 $10 PB1785 PB1785 Invasive Weeds Invasive Weeds of the of the Appalachian Appalachian Region Region i TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments……………………………………...i How to use this guide…………………………………ii IPM decision aid………………………………………..1 Invasive weeds Grasses …………………………………………..5 Broadleaves…………………………………….18 Vines………………………………………………35 Shrubs/trees……………………………………48 Parasitic plants………………………………..70 Herbicide chart………………………………………….72 Bibliography……………………………………………..73 Index………………………………………………………..76 AUTHORS Rebecca M. Koepke-Hill, Extension Assistant, The University of Tennessee Gregory R. Armel, Assistant Professor, Extension Specialist for Invasive Weeds, The University of Tennessee Robert J. Richardson, Assistant Professor and Extension Weed Specialist, North Caro- lina State University G. Neil Rhodes, Jr., Professor and Extension Weed Specialist, The University of Ten- nessee ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors would like to thank all the individuals and organizations who have contributed their time, advice, financial support, and photos to the crea- tion of this guide. We would like to specifically thank the USDA, CSREES, and The Southern Region IPM Center for their extensive support of this pro- ject. COVER PHOTO CREDITS ii 1. Wavyleaf basketgrass - Geoffery Mason 2. Bamboo - Shawn Askew 3. Giant hogweed - Antonio DiTommaso 4. Japanese barberry - Leslie Merhoff 5. Mimosa - Becky Koepke-Hill 6. Periwinkle - Dan Tenaglia 7. Porcelainberry - Randy Prostak 8. Cogongrass - James Miller 9. Kudzu - Shawn Askew Photo credit note: Numbers in parenthesis following photo captions refer to the num- bered photographer list on the back cover. HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE Tabs: Blank tabs can be found at the top of each page. These can be custom- ized with pen or marker to best suit your method of organization. Examples: Infestation present On bordering land No concern Uncontrolled Treatment initiated Controlled Large infestation Medium infestation Small infestation Control Methods: Each mechanical control method is represented by an icon. -

Weeds: Control and Prevention

Weed Control and Prevention Sheriden Hansen Assistant Professor, Horticulture USU Extension, Davis County COURSE OBJECTIVES • What is the definition of a weed • Why are weeds so difficult to control? • Annuals vs. biennials vs. perennials • Methods of spread • Noxious weeds • How to control • Methods of control • Tips to win the weed war • Common weeds and how to beat them! What is a weed? • A plant out of place • An undesirable plant • An interfering plant • “A plant whose virtues have not yet been discovered.” Ralph Waldo Emmerson • A plant that has mastered every survival skill except how to grow in rows • A plant that someone will spend time and money to kill! What is a weed? • Any plant that interferes with the management objectives for a given area of land at a given point in time. Weeds are successful survivors! • Excellent reproducers • They grow FAST • They are hardy generalists and can live just about anywhere Multiple ways of spreading! • By seed production • Seeds remain viable for YEARS! • Produce copious seeds • Runners or rhizomes/stolons • They have adapted to being spread in creative ways • Animal fur • Wind • Bird, deer, lizard digestion • Wheels Photo: Missoula County Weed District and Extension Annual vs biennial vs perennial weeds • What is an annual? • Plant that performs its entire lifecycle from seed to flower to seed in a single growing season • Dormant seed bridges the gap from one generation to the next F.D. Richards, Flickr.com Annual vs biennial vs perennial weeds • Annual weeds spread by seed only • Spurge -

Beta Cinema Presents a Purple Bench Films / Zero Gravity Films / Live Through the Heart Films / Barry Films / Furture Films Production “Walter” Andrew J

BETA CINEMA PRESENTS A PURPLE BENCH FILMS / ZERO GRAVITY FILMS / LIVE THROUGH THE HEART FILMS / BARRY FILMS / FURTURE FILMS PRODUCTION “WALTER” ANDREW J. WEST JUSTIN KIRK NEVE CAMPBELL LEVEN RAMBIN MILO VENTIMIGLIA JIM GRAFFIGAN BRIAN WHITE PETER FACINELLI VIRGINIA MADSEN WILLIAM H. MACY CASTING J.C. CANTU MUSIC DAN ROMER MUSIC SUPERVISOR KIEHR LEHMAN EDITING KRISTIN MCCASEY DIRCTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY STEVE CAPITANO CALITRI PRODUCTION DESIGN MICHAEL BRICKER COSTUMES LAUREN SCHAD EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS BILL JOHNSON SAM ENGELBARDT JENNIFER LAURENT RICK ST. GEORGE JOHN FULLER CARL RUMBAUGH TIM HILL RICKY MARGOLIS SIMON GRAHAM-CLARE WOLFGANG MUELLER MICHEL MERKT ANNA MASTRO CO-EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS STEFANIE MASTRO MICHAEL DAVID MASTRO KEITH MATSON AND JOANNE MATSON CO-PRODUCER ANTONIO SCLAFANI ASSOCIATE PRODUCER MICHAEL BRICKER PRODUCED BY MARK HOLDER CHRISTINE HOLDER BRENDEN PATRICK HILL RYAN HARRIS BENITO MUELLER WRITTEN BY PAUL SHOULBERG DIRECTED BY ANNA MASTRO Director Anna Mastro (GOSSIP GIRL) Cast William H. Macy (SHAMELESS, FARGO) Virginia Madsen (SIDEWAYS) Peter Facinelli (TWILIGHT) Andrew J. West (THE WALKING DEAD) Justin Kirk (WEEDS, MR. MORGAN‘S LAST LOVE) Neve Campbell (SCREAM, WILD THINGS) Milo Ventimiglia (HEROS, THAT´S MY BOY) Genre Comedy / Drama Language English Length 88 min Produced by Zero Gravity, Purple Bench Films, Barry Films and Demarest Films WALTER SYNOPSIS Walter believes himself to be the son of God. As such, it is his responsibility to judge whether people will spend eternity in heaven or hell. That’s a lot to manage along with his job as a ticket- tearer at a movie theater, his loving but neurotic mother, and his growing but unspoken affection for his co-worker Kendall. -

Toxic Plants

forage grazing management: crops toxic plants A Shortage of good-quality pasture can Glucosinolates Glucosinolates are natural compounds that give be a limiting factor for a cattle operation. plants a bitter, “hot” taste. Found in the leaves of Annual forage crops grown in place of fallow can certain plants, they are highly concentrated in seed. provide high-quality forage during key produc- When consumed by livestock, glucosinolates interfere tion periods and may help reduce soil erosion, with thyroid function, cause liver and kidney lesions, suppress weeds, and increase soil nutrient profiles. and reduce mineral uptake. For livestock, the most Traditionally grown for agronomic or soil benefits serious issue is inhibited iodine uptake which can but not harvested, cover crops are being considered reduce production of the hormone thyroxine and result for grazing, haying, or planting as annual forages. in goiters. They are appealing because of the potential for addi- tional revenue from improved cattle performance Grass Tetany combined with the benefits of soil stabilization. Also known as grass staggers or wheat pasture Those contemplating this decision should know that poisoning, grass tetany is a metabolic disorder char- plants that work well as cover crops may not be acterized by low magnesium levels in the blood. Grass suitable for forage or grazing. In fact, some species tetany mainly affects older lactating cows grazing succu- can be toxic or fatal to livestock. This publication lent, immature grass. It can result in uncoordinated gait describes popular cover crops and the dangers they (staggers), convulsion, coma, and death. To prevent present for grazing livestock. -

Money Laundering: an Overview of 18 U.S.C. § 1956 and Related Federal Criminal Law

Money Laundering: An Overview of 18 U.S.C. § 1956 and Related Federal Criminal Law Charles Doyle Senior Specialist in American Public Law November 30, 2017 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL33315 Money Laundering: An Overview of 18 U.S.C. § 1956 and Related Federal Criminal Law Summary This report provides an overview of the elements of federal criminal money laundering statutes and the sanctions imposed for their violation. The most prominent is 18 U.S.C. § 1956. Section 1956 outlaws four kinds of money laundering—promotional, concealment, structuring, and tax evasion laundering of the proceeds generated by designated federal, state, and foreign underlying crimes (predicate offenses)—committed or attempted under one or more of three jurisdictional conditions (i.e., laundering involving certain financial transactions, laundering involving international transfers, and stings). Its companion, 18 U.S.C. § 1957, prohibits depositing or spending more than $10,000 of the proceeds from a predicate offense. Section 1956 violations are punishable by imprisonment for not more than 20 years. Section 1957 carries a maximum penalty of imprisonment for 10 years. Property involved in either case is subject to confiscation. Misconduct that implicates either offense may implicate other federal criminal statutes as well. Federal racketeer influenced and corrupt organization (RICO) provisions outlaw acquiring or conducting the affairs of an enterprise (whose activities affect interstate or foreign commerce) through the patterned commission of a series of underlying federal or state crimes. RICO violations are also 20-year felonies. The Section 1956 predicate offense list automatically includes every RICO predicate offense, including each “federal crime of terrorism.” A second related statute, the Travel Act (18 U.S.C. -

Nestor Serrano Mayor Michael Salgado

NEW SERIES WEDNESDAY 24TH JUNE 1 \ WEDNESDAY 24TH JUNE Police work isn’t rocket science. It’s harder. Inspired by the New York Times Magazine article “Who Runs the Streets of New Becoming the city’s most advanced police district isn’t easy. Gideon knows if he’s Orleans” by David Amsden, APB is a new police drama with a high-tech twist from going to change anything, he needs help, which he finds from Detective Theresa executive producer/director Len Wiseman (Lucifer, Sleepy Hollow) and executive Murphy producers and writers Matt Nix (Burn Notice) and Trey Callaway (The Messengers). (Natalie Martinez, Kingdom, Under the Dome), an ambitious, street-smart cop who is Sky-high crime, officer-involved shootings, cover-ups and corruption: the willing to give Gideon’s technological ideas a chance. over-extended and under-funded Chicago Police Department is spiraling out of control. Enter billionaire engineer Gideon Reeves (Emmy® Award and Golden Globe® With the help of Gideon’s gifted tech officer, Ada Hamilton (Caitlin Stasey, Reign), nominee Justin Kirk, Tyrant, Weeds). After he witnesses his best friend’s murder, he he and Murphy embark on a mission to turn the 13th District – including a skeptical takes charge of Chicago’s troubled 13th District and reboots it as a technically Capt. Ned Conrad (Ernie Hudson, Grace and Frankie, Ghostbusters) and determined innovative police force, challenging the district to rethink everything about the officers way they fight crime. Nicholas Brandt (Taylor Handley, Vegas, Southland) and Tasha Goss (Tamberla Perry, Boss) – into a dedicated crime-fighting force of the 21st century. -

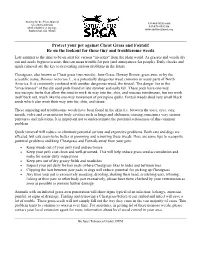

Protect Your Pet Against Cheat Grass and Foxtail!

Society for the Prevention of 831-465-5000 main Cruelty to Animals 831-479-8530 fax 2685 Chanticleer Avenue www.santacruzspca.org Santa Cruz, CA 95065 Protect your pet against Cheat Grass and Foxtail! Be on the lookout for these tiny and troublesome weeds Late summer is the time to be on alert for various "invaders" from the plant world. As grasses and weeds dry out and seeds begin to scatter, this can mean trouble for pets (and annoyances for people). Daily checks and quick removal are the key to preventing serious problems in the future. Cheatgrass, also known as Cheat grass (two words), June Grass, Downy Brome, grass awn, or by the scientific name, Bromus tectorum L., is a potentially dangerous weed common in many parts of North America. It is commonly confused with another dangerous weed, the foxtail. The danger lies in the "invasiveness" of the dry seed pods found in late summer and early fall. These pods have one-way microscopic barbs that allow the seed to work its way into fur, skin, and mucous membranes, but not work itself back out, much like the one-way movement of porcupine quills. Foxtail weeds shed very small black seeds which also work their way into fur, skin, and tissue. These annoying and troublesome weeds have been found in the skin (i.e. between the toes), eyes, ears, mouth, vulva and even interior body cavities such as lungs and abdomen, causing sometimes very serious punctures and infections. It is important not to underestimate the potential seriousness of this common problem. -

Violent Crimes in Aid of Racketeering 18 U.S.C. § 1959 a Manual for Federal Prosecutors

Violent Crimes in Aid of Racketeering 18 U.S.C. § 1959 A Manual for Federal Prosecutors December 2006 Prepared by the Staff of the Organized Crime and Racketeering Section U.S. Department of Justice, Washington, DC 20005 (202) 514-3594 Frank J. Marine, Consultant Douglas E. Crow, Principal Deputy Chief Amy Chang Lee, Assistant Chief Robert C. Dalton Merv Hamburg Gregory C.J. Lisa Melissa Marquez-Oliver David J. Stander Catherine M. Weinstock Cover Design by Linda M. Baer PREFACE This manual is intended to assist federal prosecutors in the preparation and litigation of cases involving the Violent Crimes in Aid of Racketeering Statute, 18 U.S.C. § 1959. Prosecutors are encouraged to contact the Organized Crime and Racketeering Section (OCRS) early in the preparation of their case for advice and assistance. All pleadings alleging a violation of 18 U.S.C. § 1959 including any indictment, information, or criminal complaint, and a prosecution memorandum must be submitted to OCRS for review and approval before being filed with the court. The submission should be approved by the prosecutor’s office before being submitted to OCRS. Due to the volume of submissions received by OCRS, prosecutors should submit the proposal three weeks prior to the date final approval is needed. Prosecutors should contact OCRS regarding the status of the proposed submission before finally scheduling arrests or other time-sensitive actions relating to the submission. Moreover, prosecutors should refrain from finalizing any guilty plea agreement containing a Section 1959 charge until final approval has been obtained from OCRS. The policies and procedures set forth in this manual and elsewhere relating to 18 U.S.C. -

“Good Shit Lollipop”

“GOOD SHIT LOLLIPOP” Episode # 1003 Written By Roberto Benabib Directed By Craig Zisk GREEN – 4 th REVISED 3/29/05 (pp. 8, 8A) YELLOW – 3 RD REVISED 3/24/05 PINK – 2 ND REVISED 3/23/05 BLUE – 1 ST REVISED 03/21/05 WHITE Production Draft 3/17/05 Copyright © 2005 Lions Gate Television Inc. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No portion of this script may be performed, published, sold or distributed by any means, or quoted or published in any medium, including any website, without prior written consent. Disposal of this script copy does not alter any of the restrictions set forth above. WEEDS Episode #1003 – GOOD SHIT LOLLIPOP CAST LIST Nancy Botwin ..........................................................................Mary-Louise Parker Celia Hodes .............................................................................Elizabeth Perkins Doug Wilson ............................................................................Kevin Nealon Heylia James ...........................................................................Tonye Patano Conrad Conrad Shepard ...........................................................Romany Malco Silas Botwin.............................................................................Hunter Parrish Shane Botwin ..........................................................................Alex Gould Dean Hodes.............................................................................Andy Milder Isabel Hodes ...........................................................................Allie Grant Vaneeta...................................................................................Indigo -

Money-Laundering Typologies: a Review of Their Fitness for Purpose

1 MONEY-LAUNDERING TYPOLOGIES: A REVIEW OF THEIR FITNESS FOR PURPOSE MICHAEL LEVI, PHD, DSC (ECON.) PROFESSOR OF CRIMINOLOGY, CARDIFF UNIVERSITY, UK. GOVERNMENT OF CANADA CONSULTING AND PROFESSIONAL SERVICES CONTRACT NUMBER: 06002-12-0389 OCTOBER 31 2013 2 CONTENTS PART 1: DEFINING AND CONCEPTUALISING TYPOLOGIES ................................................................... 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Conceptualising and defining laundering ............................................................................................ 4 The elastic definition of laundering ..................................................................................................... 6 Reference to the predicate crime ...................................................................................................... 9 Seriousness of the predicate crime ................................................................................................. 9 The three-stage model and typologies of money laundering .......................................................... 9 The Use of the Three Stage Typology in Policy and Practice ....................................................... 14 PART 2: LITERATURE REVIEW OF LAUNDERING TYPOLOGIES ............................................................. 16 Introduction ..............................................................................................................................................