Cultural Resources Overview for the 700 Dexter Project, King County, Washington

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MIKE SIEGEL / the SEATTLE TIMES South Lake Union 1882

Photo credit: MIKE SIEGEL / THE SEATTLE TIMES South Lake Union 1882 http://pauldorpat.com/seattle-now-and-then/seattle-now-then/ Westlake 1902 Top, Westlake 2013 The Club Stables earlier home on Western Ave. north of Lenora Street: Photo Credit MOHAI Reported in the Seattle Times Sept. 26, 1909, read the headline, "Club Stables Now In Finest Quarters in West." Article describes the scene "in the very heart of the city . These up-to-date stables contain ample accommodations for 250 horses, with every safeguard and comfort in the way of ventilation, cleanliness etc. that modern sanitary science can provide . An elaborate sprinkler system of the most approved and efficient type . is practically an absolute guarantee against serious damage by fire. The management solicits an inspection at any time." Development Western Mill, early 1890s, at the south end of Lake Union and the principal employer for the greater Cascade neighborhood Development accelerated after David Denny built the Western Mill in 1882, near the site of today’s Naval Reserve Center, and cut a barrier at Montlake to float logs between the lakes. Homes soon began to appear on the Lake Union’s south shore, ranging from the ornate Queen Anne-style mansion built by Margaret Pontius in 1889 (which served as the “Mother Ryther Home” for orphans from 1905 to 1920) to humble worker's cottages. The latter housed a growing number of immigrants from Scandinavia, Greece, Russia, and America’s own teeming East, attracted by jobs in Seattle’s burgeoning mills and on its bustling docks. Beginning in 1894, their children attended Cascade School -- which finally gave the neighborhood a name -- and families worshipped on Sundays at St. -

CSOV 120 Spring 2021 Languages of Our Ancestors

University of Washington - 2021 Urban Forest Symposium CHESHIAHUD TALKS: Historical Union Bay Forests A Family Generational View on Being Connected & Responsibility Prepared By: Jeffrey Thomas (Muckleshoot Tribal Elder; UW B.S. Zoology, M.Sc. Marine Affairs) Director: Timber, Fish & Wildlife Program/Puyallup Tribe of Indians (253) 405-7478 [email protected] ** Disclaimer – All of the photographic and timeline information assembled herein was collected from currently available digital internet sources - and thus may be inaccurate - depending upon the veracity of the sources. CHIEF DESCENDANTS Pre-1850s: Treaty Maps • 1820 – Lake John Cheshiahud born on southern Union Bay village – this was a vital passage from the coast into the lakes and river system all the way up to Issaquah and beyond. ➢ Duwamish people traveling by canoe had access to waterway connections unavailable to larger Euro-American vessels. ➢ Lake John reported to have “…a cabin on Lake Union across from the University grounds…Lake John used to take pelts to the trading station at Steilacoom before Seattle was thought of.” 1850s: Union Bay Map 1856 & Chief Cheshiahud Village Site • 1851 – Denny Party arrives to begin claiming Duwamish homelands – including Lake Union. • 1853: Washington Territory established. • 1854 – Seattle’s 1st school opens as a private/tuition school (on 1st and Madison) – then moves but continues to operate until 1861…when students were sent to classes in the new building of the Territorial University. The first year of the Territorial University, there were 37 students, of which 36 were below college level. • 1854 – Washington Territorial Legislature outlaws Non- Native men marrying Native women (but legalizes it again in 1868). -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form

IFHR-6-300 (11-78) United States Department of the Interior Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name historic Harvard - Belmont and/or common Harvard - Belmont District , not for publication city, town Seattle vicinity of congressional district state Washington code 53 county King code 033 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use X district public _ X-. occupied agriculture museum __ buitding(s) private unoccupied __X_ commercial park __ structure _X_both __ work in progress X educational _JL private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment ...... religious object in process yes: restricted government scientific .. w being considered X yes: unrestricted industrial transportation ^ no military __ other: name Multiple private ownerships; City of Seattle (public rlghts-of-way and open spaces) city, town vicinity of state 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. King County Administration Building Fourth Avenue at James Street city, town Seattle, state Washington 98104 6. Representation in Existing Surveys r.Seattle Inventory of Historic Resources, 1979 title 2. Office Of Urban Conservation has this property been determined elegible? _X_yes no burvey tor Proposed Landmark District date 1979-1980 federal state __ county _L local depository for survey records Office of Urban Conservation, -

Report on Designation Lpb 181/09

REPORT ON DESIGNATION LPB 181/09 Name and Address of Property: Naval Reserve Armory 860 Terry Avenue North Legal Description: Lots 9-13, inclusive, Block 74, Lake Union Shore Lands. Together with any and all rights to the east half of abutting street, being Terry Avenue North as shown on the ALTA/ASCM Land Title Survey of US NAVAL RESERVE CENTER SOUTH LAKE UNION dated Dec. 3, 1998. Recording number 9506309003, Volume 104, Page 116. At the public meeting held on March 18, 2009, the City of Seattle's Landmarks Preservation Board voted to approve designation of the Naval Reserve Armory at 860 Terry Avenue North Street as a Seattle Landmark based upon satisfaction of the following standards for designation of SMC 25.12.350: C. It is associated in a significant way with a significant aspect of the cultural, political, or economic heritage of the community, City, state or nation; and D. It embodies the distinctive visible characteristics of an architectural style, period, or of a method of construction; and F. Because of its prominence of spatial location, contrasts of siting, age, or scale, it is an easily identifiable visual feature of its neighborhood or the city and contributes to the distinctive quality or identity of such neighborhood or the City. DESCRIPTION The South Lake Union neighborhood is located north of the city's Central Business District, and north and east of Belltown. It is bordered by the lake on the north, Interstate 5 on the east, Denny Way on the south, and Highway 99/Aurora Avenue on the west. -

LAKE UNION Historical WALKING TOUR

B HistoryLink.org Lake Union Walking Tour | Page 1 b Introduction: Lake Union the level of Lake Union. Two years later the waters of Salmon Bay were raised behind the his is a Cybertour of Seattle’s historic Chittenden Locks to the level of Lake Union. South Lake Union neighborhood, includ- Historical T As the Lake Washington Ship Canal’s ing the Cascade neighborhood and portions Walking tour Government Locks (now Hiram of the Denny Regrade. It was written Chittenden Locks) neared its 1917 and curated by Paula Becker with completion, the shores of Lake Union the assistance of Walt Crowley and sprouted dozens of boat yards. For Paul Dorpat. Map by Marie McCaffrey. most of the remaining years of the Preparation of this feature was under- twentieth century, Lake Union was written by Vulcan Inc., a Paul G. Allen one of the top wooden-boat building Company. This Cybertour begins at centers in the world, utilizing rot- Lake Union Park, then loosely follows resistant local Douglas fir for framing the course of the Westlake Streetcar, and Western Red Cedar for planking. with forays into the Cascade neighbor- During and after World War I, a hood and into the Seattle Center area. fleet of wooden vessels built locally for the war but never used was moored Seattle’s in the center of Lake Union. Before “Little Lake” completion of the George Washington ake Union is located just north of the Washington, Salmon Bay, and Puget Sound. Memorial Bridge (called Aurora Bridge) in L geographic center and downtown core A little more than six decades later, Mercer’s 1932, a number of tall-masted ships moored of the city of Seattle. -

Methodist Pioneers, Founding Fathers of Seattle by Everett W

Methodist Pioneers, Founding Fathers of Seattle by Everett W. Palmer Presiding Bishop of the Seattle Area, The Methodist Church. ERHAPS no major city in the United States owes quite as Pmuch to Methodist pioneers as Seattle, Washington. Most of its founders were Methodists, as were those who played a dominant role in the early and decisive years of its development. Most, if not all, of the first settlers were Methodists. The &st church established was a Methodist Church. The first school was conducted by the wife of a Methodist minister in the Methodist parsonage. The first uni- versity, now the University of Washington, was founded through the initiative of a Methodist minister supported by a loyal Method- ist laity. And this is but a sample. Let us reverse the calendar a century. It is September 25,1851. A party of three men paddle up to the shore of what is now West Seattle. It is the end of a long journey. Since early April they have traveled, first by wagon train from their homes in Illinois to the Willamette Valley, and from there by foot and Indian canoe to the "Puget Sound country." They have been sent ahead by other mem- bers of their party to explore this region and determine its promise. The oldest of the group is John Low, 31. The other two are David Denny, 19, and Lee Terry, also a teen-ager. A tribe of Indians nearby is busily engaged, fishing for salmon. Their chief, a noble man of regal bearing, strides down the beach to bid them welcome. -

Winter 2013/14

The Eastlake News Winter 2013/14 Coming Events Microhousing and land use: Drive for the U District Food Bank. Dec. 2-20. ECC pays for Code Interpretation, appeals Collection barrels at Lake Union Mail, Pete’s, and citywide legislative proposal, and invites WSECU. See article on p. 13, including how to donations and volunteers donate much-needed funds. n Oct. 2, your Eastlake Community Council took an King County-Metro public meeting on bus ser- Oexpensive step (likely one of many to come) in fight- vice reduction Thurs., Dec. 5, 6–8 p.m. at North ing the destructive “land rush” now threatening our neigh- Seattle Community College, 9600 College Way N., borhood. ECC paid $2500 for up to ten hours of work by Rm. C-1161. See article, p. 4 Seattle’s Department of Planning and Development (DPD) and committed to pay for more hours if needed to produce King County-Metro public meeting on bus ser- a Land Use Code Interpretation regarding the number of vice reduction Tues., Dec. 10, 12–2 p.m. at Union Station, 401 S. Jackson St. units in the proposed microhousing project at 2719 Yale Terrace East. An additional ECC expense may be consult- Holiday cruise on ing or legal help in persuading DPD toward the result that the Islander Mon., we seek. The developer claims only 8 dwelling units but Dec. 23. Boarding ECC believes that DPD’s Code Interpretation staff will begins at 6:30 p.m. at rule that the project has 40 dwelling units. 1611 Fairview Ave. The numbers are important because of requirements that E. -

SR 520, I-5 to Medina: Bridge Replacement and HOV Project Supplemental Draft Environmental Impact Statement

SUPPLEMENTAL DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT and SECTION 4(F) EVALUATION SR 520 BRIDGE REPLACEMENT AND HOV PROGRAM DECEMBER 2009 SR 520: I-5 to Medina Bridge Replacement and HOV Project Cultural Resources Discipline Report � SR 520: I-5 to Medina Bridge Replacement and HOV Project Supplemental Draft EIS Cultural Resources Discipline Report Prepared for Washington State Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration Lead Author CH2M HILL Consultant Team Parametrix, Inc. CH2M HILL HDR Engineering, Inc. Parsons Brinckerhoff ICF Jones & Stokes Cherry Creek Consulting Michael Minor and Associates PRR, Inc. December 2009 I-5 to Medina: Bridge Replacement and HOV Project | Supplemental Draft EIS Executive Summary The I-5 to Medina: Bridge Replacement and High-Occupancy Vehicle (HOV) Project limits extend from I-5 in Seattle to 92nd Avenue NE in Yarrow Point, where this project transitions into the Medina to SR 202: Eastside Transit and HOV Project. The overall geographic area contains three study areas: Seattle, Lake Washington, and Eastside transition area. The Seattle study area includes the I-5, Portage Bay, Montlake, and West Approach areas (Exhibit 7). The Lake Washington study area extends from near 47th Avenue NE east across Lake Washington to Evergreen Point Road. The Eastside transition area study area begins at Evergreen Point Road and extends east to 92nd Avenue NE. This report also evaluates effects that might occur from the transport of pontoons that would be used to build the new floating bridge, as well as from the production and transport of supplemental pontoons. Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) initiated the Section 106 process for this undertaking in April and May, 2009, coordinating with the State Historic Preservation Officer (SHPO), Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (ACHP), affected Indian Tribes, and other consulting parties. -

The Panic of 1893: the Northwest Economy Unravelled As

WashingtonHistory.org THE PANIC OF 1893 The Northwest Economy Unravelled as the “Gilded Age” Came to a Close By J. Kingston Pierce COLUMBIA The Magazine of Northwest History, Winter 1993-94: Vol. 7, No. 4 About mid afternoon on Monday, November 22, 1893, James L. Wheatley, an intelligent-looking man from South Dakota with thin, dark hair and a mustache, walked into the lobby of Seattle's Queen City Hotel at 112 Second Avenue. He'd been staying there for about a week while looking desperately for work in his chosen field of railroading. Approaching the desk clerk, Wheatley asked when his rent on Room 19 would run out. "Today," replied the clerk. "I will not need it any longer," said Wheatley, in a calm, business-like manner, "so don't hold it for me." And with that, the guest wheeled about and trod upstairs to his room. Fifteen minutes later that same man-now with his coat tightly buttoned up, a polka-dot scarf ringing his neck and a small cap on the back of his head-came bounding back down the steps. He "walked rapidly" into an apothecary at the corner of Second Avenue and Washington Street and "without the least indication of undue eXcitement" (according to a newspaper of the time) approached the counter to announce, "I have taken a drink of carbolic acid to commit suicide." The druggist eyed the gentleman in astonishment. "When did you take it?" "Just now, in the Queen City Hotel. I have been out of work and despondent because I could not get employment and wanted to die. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 1O-9OO OMB No. 1024-OO13 (Rev. a-aa) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See Instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter *N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the Instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. 1. Name of Property ——.—.--—----——--—-^^ —— historic name bnoqualmie ^ails Hydroelectric rower riant Historic District other names/site number JN/A 2. Location street & number miles nortn ot Snoqualmie, on Hwy. ZUZ l~| not for publication city, town onoqualmie vicinity state Washington code WA county code 055 zip code 3. Classification .Ownership of Property Category of Property Number of Resources within Property IS private (H build ing (s) Contributing Noncontributing f~l public-local IS district 11 buildings S] public-State D site sites CD public-Federal CD structure T structures CH object objects T Total Name of related multiple property listing: Number of contributing resources previously Hydroelectric Plants in Washington State listed in the National Register 6 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this [3 nomination d request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

SR 520 Bridge Replacement and HOV Program Portage Bay Bridge

SR 520 Bridge Replacement and HOV Program, SR 520 I-5 to Montlake – I/C and Bridge Replacement, Draft Section 4(f) Evaluation Prepared for Washington State Department of Transportation WSDOT ESO Megaprograms 999 Third Avenue, Suite 2300 Seattle, WA 98104 206-805-2895 Lead Author Lawrence Spurgeon Consultant Team WSP USA 999 Third Avenue, Suite 3200 Seattle, WA 98104 August 12, 2020 I concur with the conclusions of this evaluation Region / Mode Official FHWA Official Date Date SR 520 Bridge Replacement and HOV Program, SR 520 I-5 to Montlake – I/C and Bridge Replacement, Draft Section 4(f) Evaluation Contents Background ...................................................................................................................... 1 Project Changes .............................................................................................................. 3 Portage Bay Bridge ............................................................................................................. 3 Portage Bay Bridge through I-5 Interchange ...................................................................... 4 Summary of City of Seattle, Stakeholder, and Community Involvement ........................... 5 Section 4(f)-Protected Properties .................................................................................. 8 Park and Recreational Resources ........................................................................................ 9 Historic Properties ............................................................................................................ -

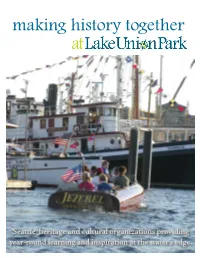

Making History Together

making history together Seattle heritage and cultural organizations providing year-round learning and inspiration at the water’s edge. P. 2 making history together Our beautiful city is fortunate to be defined by many diverse bodies of water. From Puget Sound to Lake Union through the Ship Canal to Lake Washington, from the Duwamish River to our four urban creek systems, these bodies of water in many ways define who we are as a city. They frame our sensibilities and priorities by providing habitat for mammals, fish, birds and insects. For people, they enable us to enjoy boating, fishing, kayaking, swimming, and endless beach activities. The development of Lake Union Park realizes a longtime city vision to revisit and present the rich history of the site and its relationship to the water. The Olmsted Brothers, who designed the nucleus of our park system, envisioned a grand urban park at this site. Through our partnerships with Seattle Parks Foundation, The Center for Wooden Boats, the United Indians of All Tribes, Northwest Seaport, South Lake Union Friends and Neighbors (SLUFAN), the Museum of History & Industry, and others, we are able to turn vision into reality. When newcomers first settled at the site, it was the home of the Duwamish people. Imagine their walking paths meandering through the timber, connecting the lake village with Native settlements to the east and west. Soon historic panels at the park will tell the whole history, from the arrival of the settlers through the building of the streetcar to the opening of the Ship Canal to the construction of The Boeing Airplane Company.