1953 UK Floods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The River Thames Phosphate Mode

HP NRA RIV NRA The River Thames Phosphate Mode/ Improvements on the River Colne model -* Investigation o f high decay rates -*■ Effects of phosphate stripping at STWs Gerrie Veldsink March 19% CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENT LIST OF FIGURES AND TABLES 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 THE NATIONAL RIVERS AUTHORITY AND WATER QUALITY PLANNING 2 2.1 The National River Authority 2.2 The water Quality Planning Section in the Thames Region 3 3 THE RIVER THAMES PHOSPHATE MODEL 4 3.1 Introduction 5 3.2 TOMCAT 6 4 COLNE MODEL IMPROVEMENTS 8 4.1 River Colne 8 4.2 Modelling the River Colne 9 4.2.1 Introduction 9 4.2.2 Data input 10 4.2.2.1 Flow upstream of the STWs 10 4.2.2.2 Flow downstream of the bifurcation 11 4.2.2.3 The accretional flow 11 4.2.2.4 The concentration of phosphate in the accretional flow 11 4.2.2.5 Flow and quality of discharge from STWs 11 4.2.2.6 Flow and quality of the River Misbourne 11 4.2.2.7 Sources of data and important files 12 4.2.2.8 Differences between the original model and the model in this study 13 4.2.3 Calibration (OctobeLl992 to October 1994) 14 4.2.4 Validation (lanuary 1982 to lanuary 1984) 15 4.2.5 Sensitivity ofJheXolne Mode\ 16 4.3 Conclusion 1 7 5 WORK ON THE RIVER THAMES MODEL 18 5.1 Introduction 18 5.2 Order of STW 18 5.3 High Decay Rates 18 5.3.1 Introduction 18 5.3.2 Reducing high decay rates 19 5.3 Effects of phosphate stripping at STWs 23 5.4 Conclusion 24‘ REFERENCE 25 APPENDICES Acknowledgement ACKNOWLEDGEMENT With great pleasure I fulfilled a three month practical period at the NRA Thames Region in Reading. -

Whose River? London and the Thames Estuary, 1960-2014* Vanessa Taylor Univ

This is a post-print version of an article which will appear The London Journal, 40(3) (2015), Special Issue: 'London's River? The Thames as a Contested Environmental Space'. Accepted 15 July 2015. Whose River? London and the Thames Estuary, 1960-2014* Vanessa Taylor Univ. of Greenwich, [email protected] I Introduction For the novelist A.P. Herbert in 1967 the problem with the Thames was simple. 'London River has so many mothers it doesn’t know what to do. ... What is needed is one wise, far- seeing grandmother.’1 Herbert had been campaigning for a barrage across the river to keep the tide out of the city, with little success. There were other, powerful claims on the river and numerous responsible agencies. And the Thames was not just ‘London River’: it runs for over 300 miles from Gloucestershire to the North Sea. The capital’s interdependent relationship with the Thames estuary highlights an important problem of governance. Rivers are complex, multi-functional entities that cut across land-based boundaries and create interdependencies between distant places. How do you govern a city that is connected by its river to other communities up and downstream? Who should decide what the river is for and how it should be managed? The River Thames provides a case study for exploring the challenges of governing a river in a context of changing political cultures. Many different stories could be told about the river, as a water source, drain, port, inland waterway, recreational amenity, riverside space, fishery, wildlife habitat or eco-system. -

Tidal Thames

1.0 Introduction The River Thames is probably the most recognised and best known river in the country and is often known as 'London's River' or 'Old Father Thames'. The River Thames was pivotal in the establishment of the city of London and people have lived along its banks for thousands of years. Today, over a fifth of the country’s population live within a few miles of it, and each day many thousands pass over, along and under it. The Thames is a transport route, a drain, a view, a site for redevelopment and, ever increasingly, a playground, classroom and wildlife corridor. Its habitats and species form an integral part of London’s identity and development. The tidal Thames of today is a good example of a recovering ecosystem and of great ecological importance not only to London, Kent and Essex but also to life in the North Sea and the upstream catchments of the upper Thames. Gravel foreshore, © Zoological Society of London The River Thames flows through Westminster with its high river embankments, overlooked by historic and modern buildings, crossed by seven bridges and overhung with hardy London Plane trees. In Westminster the river is tidal and exposes foreshore during low-tide over most of Tidal Thames this stretch. This foreshore is probably all that remains of the natural intertidal habitat that would have once extended The River Thames is probably the most recognised and best known river in the country and inland providing marsh and wetland areas. Within the Westminster tidal Thames plants, invertebrates and birds is often known as 'London's River' or 'Old Father Thames'. -

1953 the Text of the GATT Selected GATT

FIRST EDITION GATT BIBLIOGRAPHY 1947 - 1953 The text of the GATT Selected GATT publications A chronological list of references to the GATT GATT Secretariat Palais des Nations Gene va Switzerland March 1954 MGT/7/54 GATT BIBLIOGRAPHY This bibliography is a list of books, pamphlets, articles in periodicals, newspaper reports and editorials, and miscellaneous items including texts of lectures, which refer to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. It covers a period of approximately seven years. For six of these years - from the beginning of 1948 - the GATT has been in operation. The purpose of the list is a practical one: to provide sources of reference for historians, researchers and students. The list, it must be emphasized, is limited to the formation and operation of the GATT; for œasons •»f length, the history of the Havana Charter and its preparation and references to the proposed International Trade Organization, which has not been brought into being, have been somewhat rigidly excluded, while emphasis has been put en references that show the operational aspects of the GATT. The bibliography is divided into the following sections: 1. the text of the GATT and governmental publications; 2. selected GATT publications; (the full list of GATT publications is .obtainable from the secretariat on request) 3. a chronological listing of references to the GATT. This has been subdivided into the following periods, the references being listed alphabetically in each period: 1947 including the Geneva tariff negotiations (April- August) and -

How Has Your State Pension Age Changed?

Increase in state pension age Pensions Act 2011 WOMEN Pensions Act 2011 Date of Birth Old pension date New pension date Delay on 1995 Act 06 April 1953 to 05 May 1953 06 May 2016 06 July 2016 2 months 06 May 1953 to 05 June 1953 06 July 2016 06 November 2016 4 months 06 June 1953 to 05 July 1953 06 September 2016 06 March 2017 6 months 06 July 1953 to 05 August 1953 06 November 2016 06 July 2017 8 months 06 August 1953 to 05 September 1953 06 January 2017 06 November 2017 10 months 06 September 1953 to 05 October 1953 06 March 2017 06 March 2018 1 year 06 October 1953 to 05 November 1953 06 May 2017 06 July 2018 1 yr 2 months 06 November 1953 to 05 December 1953 06 July 2017 06 November 2018 1 yr 4 months 06 December 1953 to 05 January 1954 06 September 2017 06 March 2019 1 yr 6 months 06 January 1954 to 05 February 1954 06 November 2017 06 May 2019 1yr 6 months 06 February 1954 to 05 March 1954 06 January 2018 06 July 2019 1yr 6 months 06 March 1954 to 05 April 1954 06 March 2018 06 September 2019 1yr 6 months 06 April 1954 to 05 May 1954 06 May 2018 06 November 2019 1yr 6 months 06 May 1954 to 05 June 1954 06 July 2018 08 January 2020 1yr 6 months 06 June 1954 to 05 July 1954 06 September 2018 06 March 2020 1yr 6 months 06 July 1954 to 05 August 1954 06 November 2018 06 May 2020 1yr 6 months 06 August 1954 to 05 September 1954 06 January 2019 06 July 2020 1yr 6 months 06 September 1954 to 05 October 1954 06 March 2019 06 September 2020 1yr 6 months 06 October 1954 to 05 November 1954 06 May 2019 66th birthday at least 1 yr 5 months 06 -

Greenwich TC Visitor

Greenwich Meridian Island C to The O2 H Island R I L and Blackwall Tunnel D Gardens S A L WE RO PELTON T St. Joseph ST FERRY RO A Gardens AD C E T H ham RC Church W es N P U ath K A OO GREENWICH R LW C W ICH EET L C RO STR A AD L FERRY H B C A W AN L L A A V to East TOWN CENTRE Y S H S 6 E N O E 0 R 2 AN Greenwich Library, L T S S L A Trinity K The Forum E I DA S Thames Barrier and N T D Thames Path S R @ Greenwich OA R M Hospital O LE E R Woolwich S E A T A T H R D Tunnel T E R C E A E O ROA T G A L L A R Highbridge F O L D Greenwich Foot A M R S Wharf W . T B 16 ST R AD O E E V O S I N R R O A UT CH LN T CR I D A . LW W RD R E E Greenwich O E V O TR E AD W S RO USKAR S T A T TR T LE D E F A Pier L N D 4 O E T R R NAN O E AN OLD B B E ach I T Re R Greenwich S H Arches U ROYAL D E P G WOO L A R A R N G COLLEGE WAY S T R E Leisure D T AD ha K E RO NAVAL 6 . -

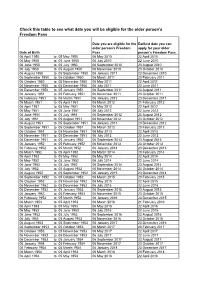

Copy of Age Eligibility from 6 April 10

Check this table to see what date you will be eligible for the older person's Freedom Pass Date you are eligible for the Earliest date you can older person's Freedom apply for your older Date of Birth Pass person's Freedom Pass 06 April 1950 to 05 May 1950 06 May 2010 22 April 2010 06 May 1950 to 05 June 1950 06 July 2010 22 June 2010 06 June 1950 to 05 July 1950 06 September 2010 23 August 2010 06 July 1950 to 05 August 1950 06 November 2010 23 October 2010 06 August 1950 to 05 September 1950 06 January 2011 23 December 2010 06 September 1950 to 05 October 1950 06 March 2011 20 February 2011 06 October 1950 to 05 November 1950 06 May 2011 22 April 2011 06 November 1950 to 05 December 1950 06 July 2011 22 June 2011 06 December 1950 to 05 January 1951 06 September 2011 23 August 2011 06 January 1951 to 05 February 1951 06 November 2011 23 October 2011 06 February 1951 to 05 March 1951 06 January 2012 23 December 2011 06 March 1951 to 05 April 1951 06 March 2012 21 February 2012 06 April 1951 to 05 May 1951 06 May 2012 22 April 2012 06 May 1951 to 05 June 1951 06 July 2012 22 June 2012 06 June 1951 to 05 July 1951 06 September 2012 23 August 2012 06 July 1951 to 05 August 1951 06 November 2012 23 October 2012 06 August 1951 to 05 September 1951 06 January 2013 23 December 2012 06 September 1951 to 05 October 1951 06 March 2013 20 February 2013 06 October 1951 to 05 November 1951 06 May 2013 22 April 2013 06 November 1951 to 05 December 1951 06 July 2013 22 June 2013 06 December 1951 to 05 January 1952 06 September 2013 23 August 2013 06 -

Parkside-Brochure.Pdf

www.parkside-e3.com Parkside is a beautifully designed new build development perfectly placed between Canary Wharf to the south, Westfield Stratford City to the north and The City of London to the west. It offers an exclusive collection of 52 private apartments and duplexes over 3 blocks. Although it’s set on a manicured park, most apartments enjoy very generous outside space – a rarity in central London these days. The development also boasts beautifully landscaped courtyards and gardens for residents’ use. For ease, all the apartments are accessible by lift. While for complete peace of mind, there’s a video entry system. Inside the apartments materials of the highest quality are used. With fully integrated designer kitchens, engineered wide board oak flooring and fully tiled luxurious bathrooms, these apartments will appeal to a discerning array of professionals and investors. In short, with its combination of a prime location, luxury finishes and excellent transport links, Parkside perfectly embodies the best of metropolitan living. A STUNNING PARKSIDE LOCATION MOMENTS FROM CANARY WHARF computer generated image FURZE GREEN & LIMEHOUSE CANAL With its setting overlooking a beautiful park just moments from one of London’s historic waterways, Parkside offers a perfect escape from the hustle of London. Just minutes from Canary Wharf and The City, residents can stretch their legs and their lungs with a multitude of open spaces to choose from. These include the Limehouse Canal, Furze Green, Mile End Park, Bartlett Park, Victoria Park (one of London’s oldest and largest). Finally the vast expanse of the largest park to be built in Europe over the past 100 years can be found minutes away at the former Olympic Park. -

THE RIVER THAMES a Complete Guide to Boating Holidays on the UK’S Most Famous River the River Thames a COMPLETE GUIDE

THE RIVER THAMES A complete guide to boating holidays on the UK’s most famous river The River Thames A COMPLETE GUIDE And there’s even more! Over 70 pages of inspiration There’s so much to see and do on the Thames, we simply can’t fit everything in to one guide. 6 - 7 Benson or Chertsey? WINING AND DINING So, to discover even more and Which base to choose 56 - 59 Eating out to find further details about the 60 Gastropubs sights and attractions already SO MUCH TO SEE AND DISCOVER 61 - 63 Fine dining featured here, visit us at 8 - 11 Oxford leboat.co.uk/thames 12 - 15 Windsor & Eton THE PRACTICALITIES OF BOATING 16 - 19 Houses & gardens 64 - 65 Our boats 20 - 21 Cliveden 66 - 67 Mooring and marinas 22 - 23 Hampton Court 68 - 69 Locks 24 - 27 Small towns and villages 70 - 71 Our illustrated map – plan your trip 28 - 29 The Runnymede memorials 72 Fuel, water and waste 30 - 33 London 73 Rules and boating etiquette 74 River conditions SOMETHING FOR EVERY INTEREST 34 - 35 Did you know? 36 - 41 Family fun 42 - 43 Birdlife 44 - 45 Parks 46 - 47 Shopping Where memories are made… 48 - 49 Horse racing & horse riding With over 40 years of experience, Le Boat prides itself on the range and 50 - 51 Fishing quality of our boats and the service we provide – it’s what sets us apart The Thames at your fingertips 52 - 53 Golf from the rest and ensures you enjoy a comfortable and hassle free Download our app to explore the 54 - 55 Something for him break. -

Thames Estuary Partnership, Taking an Estuary Walk and Having a Look at a New App Which Can Photograph GIS Informaɵon

ISSUE 4 NEWSLETTER WINTER 2016 The Thames Path Partnership includes a diverse range of organisaƟons and individuals who have an interest in the Thames Path NaƟonal Trail. In this issue we’re introducing the Thames Estuary Partnership, taking an estuary walk and having a look at a new App which can photograph GIS informaƟon. Thames Estuary Partnership News for all who enjoy the Thames Path INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Thames Estuary 1 Partnership Thames Path 2 One of our key partners on the dal Thames through London is The Thames Overview Estuary Partnership (TEP). Overseen by Pat Fitzsimons, who is also the Deputy Chair of the Thames Path Partnership, TEP is a non‐campaigning organisaon Winter Walk 3 looking aer one of the world’s premier rivers, working towards a thriving, sustainable river for London and the South‐East. They connect people, ideas 4 Wildlife along and the Thames landscape to drive social, economic and environmental im‐ the Thames provement in the Thames Estuary. The only non‐campaigning organisaon looking aer one of the world’s iconic rivers, the Partnership provides a frame‐ New Mapping 6 work for sustainable management along the Thames Estuary. App TEP runs a programme of events highlighng current issues in the estuary. If Volunteer Task 8 you become a member of TEP you will receive discounted access to these events as well as receiving a London Thames Pass. The pass gives you discount‐ Diary ed rates to fascinang and more unusual aracons on or near the Thames. Volunteer 9 The London Pass includes ‐ Fuller’s Brewery Tasng Tour, the largest Family Training Event run brewery on the Banks of the Thames in Hammersmith through to exploring Revetment on 10 Tilbury Fort which has protected London’s seaward approach from the 16th the Thames century through to the Second World War. -

The Transport System of Medieval England and Wales

THE TRANSPORT SYSTEM OF MEDIEVAL ENGLAND AND WALES - A GEOGRAPHICAL SYNTHESIS by James Frederick Edwards M.Sc., Dip.Eng.,C.Eng.,M.I.Mech.E., LRCATS A Thesis presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Salford Department of Geography 1987 1. CONTENTS Page, List of Tables iv List of Figures A Note on References Acknowledgements ix Abstract xi PART ONE INTRODUCTION 1 Chapter One: Setting Out 2 Chapter Two: Previous Research 11 PART TWO THE MEDIEVAL ROAD NETWORK 28 Introduction 29 Chapter Three: Cartographic Evidence 31 Chapter Four: The Evidence of Royal Itineraries 47 Chapter Five: Premonstratensian Itineraries from 62 Titchfield Abbey Chapter Six: The Significance of the Titchfield 74 Abbey Itineraries Chapter Seven: Some Further Evidence 89 Chapter Eight: The Basic Medieval Road Network 99 Conclusions 11? Page PART THREE THr NAVIGABLE MEDIEVAL WATERWAYS 115 Introduction 116 Chapter Hine: The Rivers of Horth-Fastern England 122 Chapter Ten: The Rivers of Yorkshire 142 Chapter Eleven: The Trent and the other Rivers of 180 Central Eastern England Chapter Twelve: The Rivers of the Fens 212 Chapter Thirteen: The Rivers of the Coast of East Anglia 238 Chapter Fourteen: The River Thames and Its Tributaries 265 Chapter Fifteen: The Rivers of the South Coast of England 298 Chapter Sixteen: The Rivers of South-Western England 315 Chapter Seventeen: The River Severn and Its Tributaries 330 Chapter Eighteen: The Rivers of Wales 348 Chapter Nineteen: The Rivers of North-Western England 362 Chapter Twenty: The Navigable Rivers of -

Loyola University New Orleans Study Abroad

For further information contact: University of East London International Office Tel: +44 (0)20 8223 3333 Email: [email protected] Visit: uel.ac.uk/international Docklands Campus University Way London E16 2RD uel.ac.uk/international Study Abroad uel.ac.uk/international Contents Page 1 Contents Page 2 – 3 Welcome Page 4 – 5 Life in London Page 6 – 9 Docklands Campus Page 10 – 11 Docklands Page 12 – 15 Stratford Campus Page 16 – 17 Stratford Page 18 – 19 London Map Page 20 – 21 Life at UEL Page 23 Study Abroad Options Page 25 – 27 Academic School Profiles Page 28 – 29 Practicalities Page 30 – 31 Accommodation Page 32 Module Choices ©2011 University of East London Welcome This is an exciting time for UEL, and especially for our students. With 2012 on the horizon there is an unprecedented buzz about East London. Alongside a major regeneration programme for the region, UEL has also been transformed. Our £170 million campus development programme has brought a range of new facilities, from 24/7 multimedia libraries and state-of-the-art clinics,to purpose-built student accommodation and, for 2011, a major new sports complex. That is why I am passionate about our potential to deliver outstanding opportunities to all of our students. Opportunities for learning, for achieving, and for building the basis for your future career success. With our unique location, our record of excellence in teaching and research, the dynamism and diversity provided by our multinational student community and our outstanding graduate employment record, UEL is a university with energy and vision. I hope you’ll like what you see in this guide and that you will want to become part of our thriving community.