Prince Edward Island Municipalities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

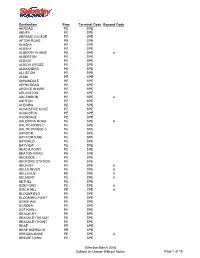

Destination Prov Terminal Code Beyond Code 48

Destination Prov Terminal Code Beyond Code 48 ROAD PE SPE ABNEY PE SPE ABRAMS VILLAGE PE SPE AFTON ROAD PE SPE ALASKA PE SPE ALBANY PE SPE ALBERRY PLAINS PE SPE A ALBERTON PE SPE ALBION PE SPE ALBION CROSS PE SPE ALEXANDRA PE SPE ALLISTON PE SPE ALMA PE SPE ANNANDALE PE SPE APPIN ROAD PE SPE ARGYLE SHORE PE SPE ARLINGTON PE SPE ASCENSION PE SPE A ASHTON PE SPE AUBURN PE SPE AUGUSTINE COVE PE SPE AUGUSTUS PE SPE AVONDALE PE SPE BALDWINS ROAD PE SPE A BALTIC KINGS C PE SPE BALTIC PRINCE C PE SPE BANGOR PE SPE BAY FORTUNE PE SPE BAYFIELD PE SPE BAYVIEW PE SPE BEACH POINT PE SPE BEATON ROAD PE SPE BEDEQUE PE SPE BEDFORD STATION PE SPE BELFAST PE SPE A BELLE RIVER PE SPE A BELLEVUE PE SPE A BELMONT PE SPE A BETHEL PE SPE BIDEFORD PE SPE A BIRCH HILL PE SPE A BLOOMFIELD PE SPE BLOOMING POINT PE SPE BONSHAW PE SPE BORDEN PE SPE BOTHWELL PE SPE BRACKLEY PE SPE BRACKLEY BEACH PE SPE BRACKLEY POINT PE SPE BRAE PE SPE BRAE HARBOUR PE SPE BREADALBANE PE SPE A BRIDGETOWN PE SPE Effective March 2008 Subject to Change Without Notice Page 1 of 10 Destination Prov Terminal Code Beyond Code BRISTOL PE SPE BROCKTON PE SPE BROOKFIELD PE SPE BROOKLYN PE SPE BROOKLYN PRINCE PE SPE A BROOKVALE PE SPE BRUDENELL PE SPE BUNBURY PE SPE BUNGAY PE SPE BURLINGTON PE SPE BURNT POINT PE SPE A BURTON PE SPE A BYRNES ROAD PE SPE CABLE HEAD PE SPE CABLE HEAD EAST PE SPE CABLE HEAD WEST PE SPE CALEDONIA PE SPE CAMBRIDGE PE SPE CAMPBELLS COVE PE SPE CAMPBELLTON PE SPE A CANAVOY PE SPE A CANOE COVE PE SPE CAPE TRAVERSE PE SPE CAPE WOLFE PE SPE CARDIGAN PE SPE CARDIGAN BAY -

Funding Report 15.16

2015-2016 Municipal Funding Report Produced by: The Department of Finance and The Department of Communities, Land and Environment 1 No part of this publication may be othewise reproduced, adapted, performed in public or transmitted in any form by any process (graphic, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or by storage in an information retrieval system) without the specific written consent of the Department of Finance. Municipal Support Grant based on Provincial Fiscal Year 2015-2016 (April 1, 2015 - March 31, 2016) 2015/16 Municipal One-time 2014/15 Increase 2015/16 2015/16 Support Grant Total 2015/16 Payment Monthly (decrease) Equalization Monthly (excluding MSG Payment (included in first Payment for in Monthly Funding Payment equalization) column) Comparison Payments Cities Charlottetown$ 10,876,141.26 $ - $ 10,876,141.26 $ 107,684.57 $ 897,371.39 $ 897,371.39 $ 0.00 Summerside 5,313,447.97 1,518,396.50 6,831,844.47 67,642.02 563,683.54 563,683.54 0.00 $ 16,189,589.23 $ 1,518,396.50 $ 17,707,985.73 $ 175,326.59 $ 1,461,054.93 $ 1,461,054.93 $ 0.00 Towns/Communities Alberton $ 171,130.96 $ 155,898.21 $ 327,029.17 $ 3,237.91 $ 26,982.61 $ 26,982.60 $ 0.00 Borden-Carleton 123,998.22 - 123,998.22 1,227.71 10,230.88 10,230.88 (0.00) Cornwall 435,301.29 310,654.58 745,955.87 7,385.70 61,547.51 61,547.51 0.00 Georgetown 94,600.42 213,840.70 308,441.12 3,053.87 25,448.94 25,448.94 (0.00) Kensington 220,969.19 121,930.30 342,899.49 3,395.04 28,292.04 28,292.04 0.00 Montague 213,597.38 296,466.79 510,064.17 5,050.14 -

Municipal Statistical Review for Prince Edward Island Municipalities for the Year

Finance and Municipal Affairs Municipal Statistical Review for Prince Edward Island municipalities for the year 2008/2009 Prepared By: Municipal Affairs and Provincial Planning Aubin Arsenault Building 3 Brighton Road Charlottetown, PE C1A 7N8 Tel: 368-5892 Fax: 368-5526 Message from the Minister __________________________________________ It is my privilege, as Minister of Finance and Municipal Affairs, to present the Municipal Statistical Review for the year of 2008. This review incorporates the statistical information on financial expenditures, population, services offered by municipalities, planning and municipal assessments. I would like to express my sincere appreciation to all municipalities for their assistance in completing the required documentation. They provided a great deal of the information in this report, along with Statistics Canada and various government departments. The result of this collaboration is an overview of the services provided by our Island municipalities to residents on a daily basis. I’m sure you will find it to be very informative. You may also find additional resources for municipalities by visiting our departmental website at: http://www.gov.pe.ca/finance/municipalaffairs Wes Sheridan Minister of Finance and Municipal Affairs Table of Contents Statistical Highlights 3 Chart 1: County Population 3 Municipal Fact Sheet 5 Chart 2: Municipal Expenditures 5 Table 1: Commercial and Non-Commercial Tax Rates 6 Chart 3: Comparison of Municipal Administration 6 Chart 4: Municipal Acreage 7 Chart 5: Municipal Populations -

Municipal Statistical Review 2012 2013

2012/13 Municipal Statistical Review Table of Contents Demographics & Geography ............................................................................................................ ‐ 1 ‐ Chart 1: PEI Population Breakdown ...................................................................................................... ‐ 1 ‐ Table 1: Municipal Populations – 2011 ................................................................................................. ‐ 2 ‐ Map 1: Municipalities in Prince Edward Island ..................................................................................... ‐ 3 ‐ Chart 2: Municipal Population Breakdown ........................................................................................... ‐ 4 ‐ Table 2: Municipal Population Breakdown by County .......................................................................... ‐ 4 ‐ Chart 3: Municipal Population Breakdown by County .......................................................................... ‐ 4 ‐ Table 3: Detailed Municipal Populations by County ............................................................................. ‐ 5 ‐ Table 4: Municipal Acreage .................................................................................................................. ‐ 6 ‐ Tax Rates ......................................................................................................................................... ‐ 7 ‐ Table 5: 2012 Non‐Commercial and Commercial Municipal Tax Rates ............................................... -

2015 Annual Report

2015 ANNUAL REPORT 58TH FPEIM ANNUAL MEETING MONDAY, MAY 25, 2015 HOSTED BY COMMUNITY OF LINKLETTER Message from the President Deputy Mayor Bruce MacDougall, City of Summerside President, FPEIM As your President, it gives me great pleasure to welcome you all to the 2015 Annual Meeting of the Federation of Prince Edward Island Municipalities. I would like to take this opportunity to thank you for taking the time out of your busy schedules. It has been an honour to work with and on behalf of Island municipalities to address municipal issues. Municipal governments face significant challenges, but by working together as a united voice through FPEIM, we will continue to make a difference and municipalities will be stronger in the years ahead. We have a full schedule, but we have included networking breaks to allow you to meet and interact with colleagues from municipalities across the province. I trust that you will find the day both productive and enjoyable. I would like to especially like to thank our host, Chairperson David Linkletter and the Community of Linkletter. A special thank you also goes to our diamond partner, Stewart McKelvey, and all the valued partners for today’s meeting. I hope you enjoy our 57th Annual Meeting, and I wish you all the best for the coming year. Sincerely, Deputy Mayor Bruce MacDougall President FPEIM 57th Annual Meeting Page: 1 April 2014 Message from the Host Municipality Chairperson David Linkletter Community of Linkletter May 25, 2015 FPEIM Annual General Meeting 2015 Welcome to the Community of Linkletter. It is a pleasure to extend greetings to all delegates and guests of the 2015 Federation of Prince Edward Island Municipalities Annual General Meeting. -

Community of Miltonvale Park Official Plan (2016)

Rural Municipality of Miltonvale Park – Official Plan (2016) RURAL MUNICIPALITY OF MILTONVALE PARK OFFICIAL PLAN 2016 AMENDED JUNE, 2019 Prepared by DV8 Consulting MAY 31, 2016 1 Rural Municipality of Miltonvale Park – Official Plan (2016) CONTENTS 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 3 2. The Rural Municipality of Miltonvale Park ...................................................................................... 4 3. Existing Land Uses ........................................................................................................................... 8 4. The Community Goal ..................................................................................................................... 11 5. Future Land Use Map Objectives .................................................................................................. 12 6. Social Objectives ............................................................................................................................ 13 7. Ecomomic Objectives .................................................................................................................... 15 8. Physical Objectives ........................................................................................................................ 16 9. Environmental Objectives ............................................................................................................. 18 10. Administration -

GST/HST Incremental Federal Rebate for Municipalities Report - January 1, 2014 to December 31 2014

GST/HST Incremental Federal Rebate for Municipalities Report - January 1, 2014 to December 31 2014 Prince Edward Island POSTAL PAYMENT LEGAL NAME CITY NAME CODE AMOUNT BELFAST COMMUNITY COUNCIL BELLE RIVER C0A $1,028.62 BONSHAW COMMUNITY BONSHAW C0A $242.18 BRACKLEY MUNICIPALITY BRACKLEY C1E $1,526.62 CAVENDISH SEWER UTILITY HUNTER RIVER C0A $1,379.53 CHARLOTTETOWN WATER COMMISSION CHARLOTTETOWN C1N $159,701.10 CITY OF CHARLOTTETOWN CHARLOTTETOWN C1A $364,609.47 CITY OF SUMMERSIDE SUMMERSIDE C1N $278,651.09 COMMUNITY OF AFTON NEW DOMINION C0A $244.24 COMMUNITY OF BORDEN-CARLETON BORDEN-CARLETON C0B $10,142.94 COMMUNITY OF CLYDE RIVER CORNWALL C0A $190.12 COMMUNITY OF CRAPAUD CRAPAUD C0A $11,327.86 COMMUNITY OF GRAND TRACADIE YORK C0A $683.69 COMMUNITY OF HAZELBROOK CHARLOTTETOWN C1A $82.36 COMMUNITY OF KINGSTON CORNWALL C0A $839.48 COMMUNITY OF KINKORA KINKORA C0B $3,911.29 COMMUNITY OF LADY SLIPPER TYNE VALLEY C0B $91.16 COMMUNITY OF LINKLETTER MISCOUCHE C1N $786.23 COMMUNITY OF MALPEQUE BAY KENSINGTON C0B $1,707.13 COMMUNITY OF MIMINEGASH MIMINEGASH C0B $820.84 COMMUNITY OF MISCOUCHE MISCOUCHE C0B $3,913.18 COMMUNITY OF MOUNT STEWART MOUNT STEWART C0A $1,558.36 COMMUNITY OF MURRAY RIVER MURRAY RIVER C0A $9,325.71 COMMUNITY OF NEW HAVEN RIVERDALE BONSHAW C0A $481.97 COMMUNITY OF NORTH RUSTICO SEWER AND WATER UTILITY CORPORATION NORTH RUSTICO C0A $55,629.87 COMMUNITY OF NORTH SHORE YORK C0A $1,923.10 COMMUNITY OF SHERBROOKE SUMMERSIDE C1N $1,383.54 COMMUNITY OF ST FELIX TIGNISH C0B $65.31 COMMUNITY OF ST NICHOLAS MISCOUCHE C0B $31.55 COMMUNITY OF ST PETERS BAY ST-PETERS BAY C0A $2,975.65 COMMUNITY OF TIGNISH TIGNISH C0B $8,339.86 COMMUNITY OF VICTORIA VICTORIA C0A $4,409.30 COMMUNITY OF YORK YORK C0A $496.57 DALTON CENTER SENIORS COMPLEX LTD TIGNISH C0B $303.93 EAST RIVER FIRE COMPANY INC. -

Dme Limited Partnership Secured Creditor Royal Bank of Canada 222 Bay Street, 24Th Floor, Toronto, on M5k1g8 18,100,924 Unsecured Creditor(S) Atlantic Graduate P

IN THE MATTER OF THE RECEIVERSHIP OF DME LIMITED PARTNERSHIP, ET AL. OF THE CITY OF CHARLOTTETOWN IN THE PROVINCE OF PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND AMOUNT DUE NAME OF CREDITOR ADDRESS (CND$) DME LIMITED PARTNERSHIP SECURED CREDITOR ROYAL BANK OF CANADA 222 BAY STREET, 24TH FLOOR, TORONTO, ON M5K1G8 18,100,924 UNSECURED CREDITOR(S) ATLANTIC GRADUATE P. O. BOX 1934, CHARLOTTETOWN,, PE, CANADA, CLA 7N5 3,117 BRAFASCO 100 GALCAT DRIVE, WOODBRIDGE, ON, CANADA, L4L 0B9 23,859 ALFA LAVAL INC C/O TH1301, P. O. BOX 4290, POSTAL STATION A, TORONTO, ON M5W 0E1 24,409 RYERSON CANADA, INC P. O. BOX 57171 C/U, STATION A, TORONTO, ON, M5W 5M5 302,504 ATLANTIC VALVE & FITTINGS LTD. 20 GALBRAITH PLACE, SAINT JOHN, NB E2M 7L1 6,216 101711PEI 54 HILLSTROM AVE, CHARLOTTETOWN, PE C1E 2C6 88,530 ATLANTIC SYSTEMS MANUFACTURING PO BOX 20043, SHERWOOD, PE C1A 9E3 78,113 ASA ALLOYS INC. 5775 KIERAN ST, SAINT-LAURENT, QC H4S 0A3 21,514 ATLANTIC FITNESS CENTRE 18 GARFIELD ST., CHARLOTTETOWN, PE CLA 6A5 447 A-CITY SPRINKLERS INC. P. O. BOX 1662, CHARLOTTETOWN, PE C1A 7N4 512 ASCO NUMATICS PO BOX 160, BRANTFORD, ON N3T 5M8 617 ATLANTIC HARDCHROME 5 NOTTING COURT, DARTMOUTH, N.S. B3B LN2 21,124 FASTSIGNS 420 QUEEN ST, CHARLOTTETOWN, PE C1A 4E6 559 ARCHON INDUSTRIES, INC. 357 SPOOK ROCK ROAD, SUFFERN, NY 10901 38,780 ACI CENTRAL INCORPORATED PO BOX 53, CHARLOTTETOWN, PE C1A 7K1 1,347 AUTOMATION DIRECT P. O. BOX 402417, ATLANTA, GA 30384-2417 7,408 ANDERSON INST CO. P. O. BOX 96060, CHICAGO, IL 60693-6060 24,536 ASB HEATING ELEMENTS LIMITED 20 BETHRIDGE RD., TORONTO, ON M9W 1N1 16,593 J & S SHEET METAL LTD. -

Booklet 14.Pdf

PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND COMMAND Military Service Recognition Booklet - Volume 14 Dedicated to all Prince Edward Islanders who served their country in times of war and peace. Proud to Honour our PEI Veterans • TV Commercials / Web Videos • Live Events / Sporting Activities • DVD Authoring and Custom Menus • DVD Duplication www.universum.ca 902-393-9100 Charlottetown, PEI O n behalf of the Government of Prince Edward Island, it is my pleasure to extend congratulations and best wishes to The Royal Canadian Legion on the occasion of the publication of the fourteenth edition of the Military Service Recognition Booklet. Islanders have had a long and proud tradition of responding to the call of duty both in times of peace and in conflict. This annual publication recognizes the importance of paying tribute to those who responded to our country’s needs, ordinary citizens who have made and continue to make extraordinary sacrifices to safeguard our peace. Let us continue to honour the memory of those who have gone before us and support those who continue to ensure the freedom we enjoy today. Lest We Forget / 1 O’Leary Residential & Commercial 351 Main Street Box 274, O’Leary, PE C0B 1V0 Securing Islanders Since 1986 902-859-2768 PO Box 235, Winsloe, PE Fax 902-859-1311 [email protected] [email protected] Route 12 902.368.3082 Charlottetown 7027 Barlow Rd 902.888.9838 Summerside Tyne Valley 902-831-2500 Proudly Supporting Our Veterans Proudly Serving Veterans And Their Families in 47 Communities For over 84 Years The Mayor and Council of the Town of Stratford are pleased to support The Royal Canadian Legion and the “Military Service Recognition Booklet” The Royal Canadian Legion Branch 8 PO Box 59 15 Douces Road Montague, PE C0A 1R0 2 / www.peilegion.com The Royal Canadian Legion Prince Edward Island Command Message from the President April 9th, 2017 marked the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Vimy Ridge. -

On Premise Signage Application

ON PREMISE SIGNAGE APPLICATION Program Outline The Highway Signage Act recognizes the Island’s landscape as the single most valuable resource or product for the tourism industry and thus establishes restrictive measures on commercial signage. The Act provides for licencing of on-premise signage and recognizes the Tourism Directional Signage Program as the means of directing traffic to eligible business premises (see separate application). The one-time fee charged for On Premise Signage permits is $25.00 plus HST - 15%. Eligibility and Application All signage meant to be seen from any public road is covered by the Highway Signage Act. Exempted are the Cities of Charlottetown and Summerside, the Resort Municipality of Stanley Bridge, Hope River, Bayview, Cavendish, North Rustico, Alberton, Borden-Carleton, Cornwall, Georgetown, Kensington, Miltonvale Park, Montague, New Haven-Riverdale, Stratford and Souris all of which administer their own their own signage by-laws, maintaining provincial standards. General Requirements On-premise signs advertising a business, commodity, service industry or any activity that is being sold, offered or conducted are controlled by the Act. On-premise signage must be erected on the property where the business operates. Size is limited to 32 sq. ft. at the property line but may increase by 1 sq. ft. for each linear foot the sign is set back from the property line to a maximum of 150 sq. ft.. The height of an individual sign must not exceed 26 ft.. For More Information Tourism PEI staff are experienced in dealing with signage inquiries and applications are handled quickly. Additional information can be obtained from our Compliance Division; Dave Lawless, (902-368-4883) [email protected] or, Jason Thistle, (902-368-4398) [email protected]. -

Community of Miltonvale Park Official Plan (2016)

Community of Rural Municipality of Miltonvale Park – Official Plan (2016) COMMUNITY OF RURAL MUNICIPALITY OF MILTONVALE PARK OFFICIAL PLAN 2016 AMENDED XXXXXX, 2019 Prepared by DV8 Consulting MAY 31, 2016 1 Community of Rural Municipality of Miltonvale Park – Official Plan (2016) CONTENTS 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 3 2. The Community of Rural Municipality of Miltonvale Park .............................................................. 4 3. Existing Land Uses ........................................................................................................................... 8 4. The Community Goal ..................................................................................................................... 10 5. Future Land Use Map Objectives .................................................................................................. 11 6. Social Objectives ............................................................................................................................ 12 7. Ecomomic Objectives .................................................................................................................... 15 8. Physical Objectives ........................................................................................................................ 16 9. Environmental Objectives ............................................................................................................ -

Ma 2010Statsrep.Pdf

2010/11 Municipal Statistical Review Table of Contents Map 1: Municipalities in Prince Edward Island ................................................................................. ‐ 1 ‐ Geography & Demographics ............................................................................................................ ‐ 2 ‐ Chart 1: Municipal Population ...................................................................................................... ‐ 2 ‐ Table 1: Municipal Populations .................................................................................................... ‐ 3 ‐ Map 2: Populations by County in Prince Edward Island ................................................................ ‐ 4 ‐ Table 2: Municipalities by County ................................................................................................. ‐ 5 ‐ Chart 2: Municipal Acreage Range ................................................................................................ ‐ 6 ‐ Table 3: Acreage by Municipality .................................................................................................. ‐ 7 ‐ Tax Rates ......................................................................................................................................... ‐ 8 ‐ Table 4: 2011 Commercial and Non‐Commercial Municipal Tax Rates .......................................... ‐ 8 ‐ Table 5: 2010 Commercial and Non‐Commercial Municipal Tax Rates .......................................... ‐ 8 ‐ Map 3: 2010 Municipal Non‐Commercial Tax