Parker-Davis Project History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Little Colorado River Project: Is New Hydropower Development the Key to a Renewable Energy Future, Or the Vestige of a Failed Past?

COLORADO NATURAL RESOURCES, ENERGY & ENVIRONMENTAL LAW REVIEW The Little Colorado River Project: Is New Hydropower Development the Key to a Renewable Energy Future, or the Vestige oF a Failed Past? Liam Patton* Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................ 42 I. THE EVOLUTION OF HYDROPOWER ON THE COLORADO PLATEAU ..... 45 A. Hydropower and the Development of Pumped Storage .......... 45 B. History of Dam ConstruCtion on the Plateau ........................... 48 C. Shipping ResourCes Off the Plateau: Phoenix as an Example 50 D. Modern PoliCies for Dam and Hydropower ConstruCtion ...... 52 E. The Result of Renewed Federal Support for Dams ................. 53 II. HYDROPOWER AS AN ALLY IN THE SHIFT TO CLEAN POWER ............ 54 A. Coal Generation and the Harms of the “Big Buildup” ............ 54 B. DeCommissioning Coal and the Shift to Renewable Energy ... 55 C. The LCR ProjeCt and “Clean” Pumped Hydropower .............. 56 * J.D. Candidate, 2021, University oF Colorado Law School. This Note is adapted From a final paper written for the Advanced Natural Resources Law Seminar. Thank you to the Colorado Natural Resources, Energy & Environmental Law Review staFF For all their advice and assistance in preparing this Note For publication. An additional thanks to ProFessor KrakoFF For her teachings on the economic, environmental, and Indigenous histories of the Colorado Plateau and For her invaluable guidance throughout the writing process. I am grateFul to share my Note with the community and owe it all to my professors and classmates at Colorado Law. COLORADO NATURAL RESOURCES, ENERGY & ENVIRONMENTAL LAW REVIEW 42 Colo. Nat. Resources, Energy & Envtl. L. Rev. [Vol. 32:1 III. ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS OF PLATEAU HYDROPOWER ............... -

Arizona Fishing Regulations 3 Fishing License Fees Getting Started

2019 & 2020 Fishing Regulations for your boat for your boat See how much you could savegeico.com on boat | 1-800-865-4846insurance. | Local Offi ce geico.com | 1-800-865-4846 | Local Offi ce See how much you could save on boat insurance. Some discounts, coverages, payment plans and features are not available in all states or all GEICO companies. Boat and PWC coverages are underwritten by GEICO Marine Insurance Company. GEICO is a registered service mark of Government Employees Insurance Company, Washington, D.C. 20076; a Berkshire Hathaway Inc. subsidiary. TowBoatU.S. is the preferred towing service provider for GEICO Marine Insurance. The GEICO Gecko Image © 1999-2017. © 2017 GEICO AdPages2019.indd 2 12/4/2018 1:14:48 PM AdPages2019.indd 3 12/4/2018 1:17:19 PM Table of Contents Getting Started License Information and Fees ..........................................3 Douglas A. Ducey Governor Regulation Changes ...........................................................4 ARIZONA GAME AND FISH COMMISSION How to Use This Booklet ...................................................5 JAMES S. ZIELER, CHAIR — St. Johns ERIC S. SPARKS — Tucson General Statewide Fishing Regulations KURT R. DAVIS — Phoenix LELAND S. “BILL” BRAKE — Elgin Bag and Possession Limits ................................................6 JAMES R. AMMONS — Yuma Statewide Fishing Regulations ..........................................7 ARIZONA GAME AND FISH DEPARTMENT Common Violations ...........................................................8 5000 W. Carefree Highway Live Baitfish -

Chapter One – Existing Conditions

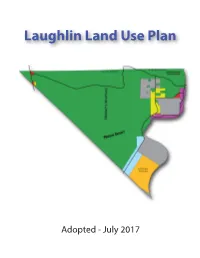

Laughlin Land Use Plan Adopted - July 2017 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Clark County Board of Commissioners: Laughlin Town Advisory Board: Steve Sisolak, Chair James Maniaci, Chair Susan Brager, Vice-Chair Kathy Ochs, Vice-Chair Larry Brown Stephanie Bethards Chris Giunchigliani Bruce Henry Marilyn Kirkpatrick Gina Mackey Mary Beth Scow Tammy Harris, Secretary Lawrence Weekly Brian Paulson, County Liaison Office of County Manager: Planning Commission: Yolanda King, Manager Dan Shaw, Chair Randy Tarr, Assistant Manager J. Dapper, Vice-Chair Jeff Wells, Assistant Manager Edward Frasier III Kevin Schiller, Assistant Manager Vivian Kilarski Tom Morley Department of Comprehensive Planning: Nelson Stone Nancy Amundsen, Director Donna Tagliaferrri Community Planning Team: Mario Bermudez, Planning Manager Shane Ammerman, Assistant Planning Manager Kevin Smedley, Principal Planner & Project Lead Paul Doerr, Senior Planner Chris LaMay, GIS Analyst Garrett TerBerg, Principal Planner Michael Popp, Sr. Management Analyst Justin Williams, Parks Planner Ron Gregory, Trails Assistant Planning Manager Scott Hagen, Senior Planner Laughlin Land Use Plan 2017 i ii Laughlin Land Use Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1 State Law ............................................................................................................ 1 Background ......................................................................................................... 1 Purpose -

Grand Canyon Helicopter Tours

GRAND CANYON HELICOPTER TOURS * * $289 Adult • $269 Child (Ages 2 - 11) + $35 Fees $364 Adult • $344 Child (Ages 2 - 11) + $80 Fees GRAND CANYON SOAR LIKE AN EAGLE THROUGH THE GRAND CANYON • Descend 4,000 feet into the Grand Canyon MOST AND SEE THE BEAUTIFUL BOWL OF FIRE. • Touch down by the banks of the Colorado River POPULAR • Champagne picnic under an authentic Hualapai Indian shelter TOUR! & Las Vegas Tours • Air only excursion through the Grand Canyon • Views of Lake Mead, Hoover Dam, Fortication Hill and the Grand Wash Clis • Views of Lake Mead, Hoover Dam, Fortification Hill and the Grand Wash Clis • Tour Duration: Approximately 4 hours (hotel to hotel) World’s Largest Grand Canyon Air Tour Company, since 1965! • Tour Duration: Approximately 3 hours (hotel to hotel) • $40 SUNSET UPGRADE (PBW-4S) • ADD LIMO TRANSFERS & STRIP FLIGHT (PLW-1) $404 Adult • $384 Child (ages 2-11) + $80 Fees $349 Adult • $329 Child (Ages 2-11) + $40 Fees • ADD LIMO TRANSFERS & STRIP FLIGHT (PLW-4) $414 Adult • $394 Child (ages 2-11) + $80 Fees • ADD LIMO TRANSFERS, SUNSET & STRIP FLIGHT (PLW-4S) $454 Adult • $434 Child (ages 2-11) + $80 Fees $94 Adult • $74 Child (Ages 2 - 11) + $10 Fees TAKE TO THE SKIES OVER THE DAZZLING AND WORLD FAMOUS LAS VEGAS "STRIP"! • Views of the MGM, New York New York, Caesar’s Palace, Bellagio, Mirage and more • Fly by the Stratosphere Tower and downtown Glitter Gulch where Las Vegas began • Complimentary champagne toast L’excursion aérienne Die vielseitigste Papillon- Veleggiate al di sotto del キャニオン上空を低 La visita aérea más • Tour Duration: Approx. -

Current Hydraulic Laboratory Research in the United States

Reference No. YI-6/lNHU U. S. DEPARTMENT OR COMMERCE NATIONAL BUREAU OR STANDARDS Lyman J. Briggs Director V \> X .2 ' v National Bureau of Standards Hydraulic Laboratory Bulletin Series A CURRENT HYDRAULIC LABORATORY RESEARCH IN THE UNITED STATES. Bulletin IV-1 January 1, 193^ WASHINGTON TABLE OF CONTENTS. Page Introduction. 1 Current projects in hydraulic laboratories. 2 Completed projects. 1. Abstracts.. ... 73 " 11 2. Publications. 79 References to publications.... 79 Translations.. 82 Foreign pamphlets received by the National Bureau of Standards.. 84 Hydraulic Research in India. 89 The Scientific Research Institute.for Hydrotechnics at Leningrad. 90 U.S.S.R. Commission for Exchange of Hydraulic Laboratory Research Results. 91 International Association for Research on Hydraulic Structures... 92 Hydraulic Research Committees. 9° Glossaries and Standard Symbols for Use in.Hydraulics. 99 Index to Pi’ojects. 100 DIRECTORY. Baldwin-Southwark Corporation, 2 Philadelphia, Pa. California, University of, 3» 02 College of Engineering and Tidal Model Laboratory, Berkeley, California. California., University of, College of Agriculture, Davis, California. 66 California Institute of Technology, 67 Pasadena, California. Carnegie Institute of Technology, Pittsburgh, pa. 39 Case School of Applied Science, 6 Department of Civil Engineering, Cleveland, Ohio. Cornell University, 11,79 School of Civil Engineering, Ithaca^ H. Y. Harvard University, 11 The Harvard Engineering School, Cambridge, Mass. Horton Hydraulic and Hydrologic Laboratory, 12 Voorheesville, Now York. Page Illinois, University of, 14 Urbaaa, Illinois. Iowa Institute of Hydraulic Research, 15, 79 The State University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa. Louisiana State University and Agricultural raid Mechanical College, 23 Baton Rouge, La. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 25 Department of Civil and Sanitary Engineering, Camsridge A, Mass. -

The Colorado River Aqueduct

Fact Sheet: Our Water Lifeline__ The Colorado River Aqueduct. Photo: Aerial photo of CRA Investment in Reliability The Colorado River Aqueduct is considered one of the nation’s Many innovations came from this period in time, including the top civil engineering marvels. It was originally conceived by creation of a medical system for contract workers that would William Mulholland and designed by Metropolitan’s first Chief become the forerunner for the prepaid healthcare plan offered Engineer Frank Weymouth after consideration of more than by Kaiser Permanente. 50 routes. The 242-mile CRA carries water from Lake Havasu to the system’s terminal reservoir at Lake Mathews in Riverside. This reservoir’s location was selected because it is situated at the upper end of Metropolitan’s service area and its elevation of nearly 1,400 feet allows water to flow by gravity to the majority of our service area The CRA was the largest public works project built in Southern California during the Great Depression. Overwhelming voter approval in 1929 for a $220 million bond – equivalent to a $3.75 billion investment today – brought jobs to 35,000 people. Miners, engineers, surveyors, cooks and more came to build Colorado River the aqueduct, living in the harshest of desert conditions and Aqueduct ultimately constructing 150 miles of canals, siphons, conduits and pipelines. They added five pumping plants to lift water over mountains so deliveries could then flow west by gravity. And they blasted 90-plus miles of tunnels, including a waterway under Mount San Jacinto. THE METROPOLITAN WATER DISTRICT OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA // // JULY 2021 FACT SHEET: THE COLORADO RIVER AQUEDUCT // // OUR WATER LIFELINE The Vision Despite the city of Los Angeles’ investment in its aqueduct, by the early 1920s, Southern Californians understood the region did not have enough local supplies to meet growing demands. -

3.6 Riverflow Issues

AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT & ENVIRONMENTAL CONSEQUENCES CHAPTER 3 3.6 RIVERFLOW ISSUES 3.6.1 INTRODUCTION This section considers the potential effects of interim surplus criteria on three types of releases from Glen Canyon Dam and Hoover Dam. The Glen Canyon Dam releases analyzed are those needed for restoration of beaches and habitat along the Colorado River between the Glen Canyon Dam and Lake Mead, and for a yet to be defined program of low steady summer flows to be provided for the study and recovery of endangered Colorado River fish, in years when releases from the dam are near the minimum. The Hoover Dam releases analyzed are the frequency of flood releases from the dam and the effect of flood flows along the river downstream of Hoover Dam. 3.6.2 BEACH/HABITAT-BUILDING FLOWS The construction and operation of Glen Canyon Dam has caused two major changes related to sediment resources downstream in Glen Canyon and Grand Canyon. The first is reduced sediment supply. Because the dam traps virtually all of the incoming sediment from the Upper Basin in Lake Powell, the Colorado River is now released from the dam as clear water. The second major change is the reduction in the high water zone from the level of pre-dam annual floods to the level of powerplant releases. Thus, the height of annual sediment deposition and erosion has been reduced. During the investigations leading to the preparation of the Operation of Glen Canyon Dam Final EIS (Reclamation, 1995b), the relationships between releases from the dam and downstream sedimentation processes were brought sharply into focus, and flow patterns designed to conserve sediment for building beaches and habitat (i.e., beach/habitat-building flow, or BHBF releases) were identified. -

Preface Chapter 1

Notes Preface 1. Alfred Pearce Dennis, “Humanizing the Department of Commerce,” Saturday Evening Post, June 6, 1925, 8. 2. Herbert Hoover, Memoirs: The Cabinet and the Presidency, 1920–1930 (New York: Macmillan, 1952), 184. 3. Herbert Hoover, “The Larger Purposes of the Department of Commerce,” in “Republi- can National Committee, Brief Review of Activities and Policies of the Federal Executive Departments,” Bulletin No. 6, 1928, Herbert Hoover Papers, Campaign and Transition Period, Box 6, “Subject: Republican National Committee,” Hoover Presidential Library, West Branch, Iowa. 4. Herbert Hoover, “Responsibility of America for World Peace,” address before national con- vention of National League of Women Voters, Des Moines, Iowa, April 11, 1923, Bible no. 303, Hoover Presidential Library. 5. Bruce Bliven, “Hoover—And the Rest,” Independent, May 29, 1920, 275. Chapter 1 1. John W. Hallowell to Arthur (Hallowell?), November 21, 1918, Hoover Papers, Pre-Com- merce Period, Hoover Presidential Library, West Branch, Iowa, Box 6, “Hallowell, John W., 1917–1920”; Julius Barnes to Gertrude Barnes, November 27 and December 5, 1918, ibid., Box 2, “Barnes, Julius H., Nov. 27, 1918–Jan. 17, 1919”; Lewis Strauss, “Further Notes for Mr. Irwin,” ca. February 1928, Subject File, Lewis L. Strauss Papers, Hoover Presidential Library, West Branch, Iowa, Box 10, “Campaign of 1928: Campaign Literature, Speeches, etc., Press Releases, Speeches, etc., 1928 Feb.–Nov.”; Strauss, handwritten notes, December 1, 1918, ibid., Box 76, “Strauss, Lewis L., Diaries, 1917–19.” 2. The men who sailed with Hoover to Europe on the Olympic on November 18, 1918, were Julius Barnes, Frederick Chatfi eld, John Hallowell, Lewis Strauss, Robert Taft, and Alonzo Taylor. -

The Future of the Salton Sea with No Restoration Project

HAZARD The Future of the Salton Sea With No Restoration Project MAY 2006 © Copyright 2006, All Rights Reserved ISBN No. 1-893790-12-6 ISBN-13: 978-1-893790-12-4 Pacific Institute 654 13th Street, Preservation Park Oakland, CA 94612 Telephone (510) 251-1600 Facsimile (510) 251-2203 [email protected] www.pacinst.org HAZARD The Future of the Salton Sea With No Restoration Project Michael J. Cohen and Karen H. Hyun A report of the MAY 2006 Prepared with the support of The Salton Sea Coalition & Imperial Visions The U.S. Geological Survey Salton Sea Science Office and the Compton Foundation About the Authors Michael Cohen is a Senior Associate at the Pacific Institute. He is the lead author of the Institute’s 1999 report entitled Haven or Hazard: The Ecology and Future of the Salton Sea, and of the 2001 report entitled Missing Water: The Uses and Flows of Water in the Colorado River Delta Region. He is also the co-author of several journal articles on water and the environment in the border region. He is a member of the California Resources Agency’s Salton Sea Advisory Committee. Karen Hyun is a Ph.D. candidate in the Marine Affairs Program at the University of Rhode Island. Her research interests include ecosystem-based management and governance, especially in the Colorado River Delta. She also has interests in transboundary water issues, authoring Solutions Lie Between the Extremes: The Evolution of International Watercourse Law on the Colorado River. In addition, she has examined watershed to coast issues in Transboundary Solutions to Environmental Problems in the Gulf of California Large Marine Ecosystem. -

ATTACHMENT B Dams and Reservoirs Along the Lower

ATTACHMENTS ATTACHMENT B Dams and Reservoirs Along the Lower Colorado River This attachment to the Colorado River Interim Surplus Criteria DEIS describes the dams and reservoirs on the main stream of the Colorado River from Glen Canyon Dam in Arizona to Morelos Dam along the international boundary with Mexico. The role that each plays in the operation of the Colorado River system is also explained. COLORADO RIVER INTERIM SURPLUS CRITERIA DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT COLORADO RIVER DAMS AND RESERVOIRS Lake Powell to Morelos Dam The following discussion summarizes the dams and reservoirs along the Colorado River from Lake Powell to the Southerly International Boundary (SIB) with Mexico and their specific roles in the operation of the Colorado River. Individual dams serve one or more specific purposes as designated in their federal construction authorizations. Such purposes are, water storage, flood control, river regulation, power generation, and water diversion to Arizona, Nevada, California, and Mexico. The All-American Canal is included in this summary because it conveys some of the water delivered to Mexico and thereby contributes to the river system operation. The dams and reservoirs are listed in the order of their location along the river proceeding downstream from Lake Powell. Their locations are shown on the map attached to the inside of the rear cover of this report. Glen Canyon Dam – Glen Canyon Dam, which formed Lake Powell, is a principal part of the Colorado River Storage Project. It is a concrete arch dam 710 feet high and 1,560 feet wide. The maximum generating discharge capacity is 33,200 cfs which may be augmented by an additional 15,000 cfs through the river outlet works. -

Eocene–Early Miocene Paleotopography of the Sierra Nevada–Great Basin–Nevadaplano Based on Widespread Ash-Flow Tuffs and P

Origin and Evolution of the Sierra Nevada and Walker Lane themed issue Eocene–Early Miocene paleotopography of the Sierra Nevada–Great Basin–Nevadaplano based on widespread ash-fl ow tuffs and paleovalleys Christopher D. Henry1, Nicholas H. Hinz1, James E. Faulds1, Joseph P. Colgan2, David A. John2, Elwood R. Brooks3, Elizabeth J. Cassel4, Larry J. Garside1, David A. Davis1, and Steven B. Castor1 1Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology, University of Nevada, Reno, Nevada 89557, USA 2U.S. Geological Survey, Menlo Park, California 94025, USA 3California State University, Hayward, California 94542, USA 4Department of Earth and Environment, Franklin & Marshall College, Lancaster, Pennsylvania 17604, USA ABSTRACT the great volume of erupted tuff and its erup- eruption fl owed similar distances as the mid- tion after ~3 Ma of nearly continuous, major Cenozoic tuffs at average gradients of ~2.5–8 The distribution of Cenozoic ash-fl ow tuffs pyroclastic eruptions near its caldera that m/km. Extrapolated 200–300 km (pre-exten- in the Great Basin and the Sierra Nevada of probably fi lled in nearby topography. sion) from the Pacifi c Ocean to the central eastern California (United States) demon- Distribution of the tuff of Campbell Creek Nevada caldera belt, the lower gradient strates that the region, commonly referred and other ash-fl ow tuffs and continuity of would require elevations of only 0.5 km for to as the Nevadaplano, was an erosional paleovalleys demonstrates that (1) the Basin valley fl oors and 1.5 km for interfl uves. The highland that was drained by major west- and Range–Sierra Nevada structural and great eastward, upvalley fl ow is consistent and east-trending rivers, with a north-south topographic boundary did not exist before with recent stable isotope data that indicate paleodivide through eastern Nevada. -

When the Navajo Generating Station Closes, Where Does the Water Go?

COLORADO NATURAL RESOURCES, ENERGY & ENVIRONMENTAL LAW REVIEW When the Navajo Generating Station Closes, Where Does the Water Go? Gregor Allen MacGregor* INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................... 291 I. HISTORICAL SETTING OF THE CURRENT CONFLICT .......................... 292 A. “Discovery” of the Colorado River; Spanish Colonization Sets the Stage for European Expansion into the Southwest ....... 292 B. American Indian Law: Sovereignty, Trust Responsibility, and Treaty Interpretation ........................................................... 293 C. Navajo Conflict and Resettlement on their Historic Homelands ............................................................................................ 295 D. Navajo Generating Station in the Context of the American Southwest’s “Big Buildup” ................................................. 297 II. OF MILLET AND MINERS: WATER LAW IN THE WEST, ON THE RESERVATIONS, AND ON THE COLORADO.................................. 301 A. Prior Appropriation: First in Time, First in Right ................ 302 B. The Winters Doctrine and the McCarran Amendment ......... 303 D. River, the Law of ................................................................. 305 1. Introduction.................................................................... 305 2. The Colorado River Compact ........................................ 306 3. Conflict in the Lower Basin Clarifies Winters .............. 307 * Mr. MacGregor is a retired US Army Cavalry Officer. This