AW Chapt 1.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Deconstruction of Sunnite Theory of Caliphate Spreading the Rule of Law on the Earth

JISMOR 6 Hassan Ko Nakata The deconstruction of Sunnite Theory of Caliphate Spreading the Rule of Law on the Earth Hassan Ko Nakata Abstract The concept of the Sunnicaliphate is self-defined as the notion that a caliph is selected by the people (ikhtiyār) and is based on the denial of the concept of the Shiite Imamate that an imam is appointed by God (naṣṣ). In today’s academic society in the field of Islamic politics, Sunni political scholars, by taking this notion of the caliphate as a starting point, attempt to position the caliphate system as a variant of the Western democracy that selects leaders through election. On the other hand, the Western scholars criticize the caliphate system as a form of dictatorship on several grounds, including the lifetime tenure of the caliph. This paper aims to deconstruct the concept of the Sunni caliphate in the context of globalism and to redefine it as “a mechanism to bring about the Rule of Law on Earth,” taking hints from the thought of Ibn Taymīyah (d.1328), who reconstructed the concept of Islamic - politics as “politics based on Sharī‘ah” by shifting the focus of the concept of Islamic politics from a caliphate to Sharī ah (≒Islamic law). If the caliphate system is to be understood as “a mechanism to bring about the Rule of Law on Earth,” we should be aware that the concepts (such as democracy and dictatorship) of modern Western political science originate in the Western tradition dating from the age of ancient Greece, which regards politics as a means to rule people by people. -

Chapter 16: India and the Indian Ocean Basin During the Postclassical Period There Emerged in India No Long-Lasting Imperial

Chapter 16: India and the Indian Ocean Basin During the postclassical period there emerged in India no long‐lasting imperial authority, as there were in China and the Islamic world. Regional kingdoms were the norm. Nevertheless, Indian society exerted a profound influence on the cultures of south and southeast Asia. Through the extensive trade networks of the Indian Ocean basin, Indian forms of political organization, religion, and economic practices spread throughout the region. Several developments in India during this era gradually spread throughout the larger culture zone. • Dramatic agricultural growth fueled population growth and urbanization. These phenomena, combined with specialized industrial production and trade, resulted in unprecedented economic growth for the region. • Indiaʹs central position in the Indian Ocean basin resulted in it becoming a major clearinghouse for products of the voluminous maritime trade network that encompassed east Africa, Arabia, Persia, southeast Asia, and Malaysia as well as the entire Indian subcontinent. • Islam originally appeared in India through a variety of conduits, and it eventually became the primary religion of one quarter of the population. From India, Islam, along with Hinduism and Buddhism, spread to southeast Asia and the nearby islands. THE CHAPTER IN PERSPECTIVE India, just as did Greece, Rome, Constantinople, and China, played an influential role in shaping neighboring societies, in this case south and Southeast Asia. The great difference between the situation in India and that of the other states was that no Indian state would develop to rival the political authority of the Tang or Roman states. Nevertheless, India’s distinctive political, cultural, and religious traditions continued to evolve and influence its neighbors. -

Republic of Iraq

Republic of Iraq Babylon Nomination Dossier for Inscription of the Property on the World Heritage List January 2018 stnel oC fobalbaT Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 1 State Party .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Province ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Name of property ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Geographical coordinates to the nearest second ................................................................................................. 1 Center ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 N 32° 32’ 31.09”, E 44° 25’ 15.00” ..................................................................................................................... 1 Textural description of the boundary .................................................................................................................. 1 Criteria under which the property is nominated .................................................................................................. 4 Draft statement -

Download Download

Nisan / The Levantine Review Volume 4 Number 2 (Winter 2015) Identity and Peoples in History Speculating on Ancient Mediterranean Mysteries Mordechai Nisan* We are familiar with a philo-Semitic disposition characterizing a number of communities, including Phoenicians/Lebanese, Kabyles/Berbers, and Ismailis/Druze, raising the question of a historical foundation binding them all together. The ethnic threads began in the Galilee and Mount Lebanon and later conceivably wound themselves back there in the persona of Al-Muwahiddun [Unitarian] Druze. While DNA testing is a fascinating methodology to verify the similarity or identity of a shared gene pool among ostensibly disparate peoples, we will primarily pursue our inquiry using conventional historical materials, without however—at the end—avoiding the clues offered by modern science. Our thesis seeks to substantiate an intuition, a reading of the contours of tales emanating from the eastern Mediterranean basin, the Levantine area, to Africa and Egypt, and returning to Israel and Lebanon. The story unfolds with ancient biblical tribes of Israel in the north of their country mixing with, or becoming Lebanese Phoenicians, travelling to North Africa—Tunisia, Algeria, and Libya in particular— assimilating among Kabyle Berbers, later fusing with Shi’a Ismailis in the Maghreb, who would then migrate to Egypt, and during the Fatimid period evolve as the Druze. The latter would later flee Egypt and return to Lebanon—the place where their (biological) ancestors had once dwelt. The original core group was composed of Hebrews/Jews, toward whom various communities evince affinity and identity today with the Jewish people and the state of Israel. -

Africans: the HISTORY of a CONTINENT, Second Edition

P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 This page intentionally left blank ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 africans, second edition Inavast and all-embracing study of Africa, from the origins of mankind to the AIDS epidemic, John Iliffe refocuses its history on the peopling of an environmentally hostilecontinent.Africanshavebeenpioneersstrugglingagainstdiseaseandnature, and their social, economic, and political institutions have been designed to ensure their survival. In the context of medical progress and other twentieth-century innovations, however, the same institutions have bred the most rapid population growth the world has ever seen. The history of the continent is thus a single story binding living Africans to their earliest human ancestors. John Iliffe was Professor of African History at the University of Cambridge and is a Fellow of St. John’s College. He is the author of several books on Africa, including Amodern history of Tanganyika and The African poor: A history,which was awarded the Herskovits Prize of the African Studies Association of the United States. Both books were published by Cambridge University Press. i P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 african studies The African Studies Series,founded in 1968 in collaboration with the African Studies Centre of the University of Cambridge, is a prestigious series of monographs and general studies on Africa covering history, anthropology, economics, sociology, and political science. -

The Ancient Greek Trireme: a Staple of Ancient Maritime Tradition

Wright State University CORE Scholar Classics Ancient Science Fair Religion, Philosophy, and Classics 2020 The Ancient Greek Trireme: A staple of Ancient Maritime Tradition Joseph York Wright State University - Main Campus, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/ancient_science_fair Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, and the Military History Commons Repository Citation York , J. (2020). The Ancient Greek Trireme: A staple of Ancient Maritime Tradition. Dayton, Ohio. This Poster is brought to you for free and open access by the Religion, Philosophy, and Classics at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Classics Ancient Science Fair by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Origin of the Trireme: The Ancient Greek Trireme: A staple of Ancient Maritime Tradition The Trireme likely evolved out of the earlier Greek ships such as the earlier two decked biremes often depicted in a number of Greek pieces of pottery, according to John Warry. These ships depicted in Greek pottery2 were sometimes show with or without History of the Trireme: parexeiresia, or outriggers. The invention of the Trireme is attributed The Ancient Greek Trireme was a to the Sidonians according to Clement staple ship of Greek naval warfare, of Alexandria in the Stromata. and played a key role in the Persian However, Thucydides claims that the Wars, the creation of the Athenian Trireme was invented by the maritime empire, and the Corinthians in the late 8th century BC. -

2 the Assyrian Empire, the Conquest of Israel, and the Colonization of Judah 37 I

ISRAEL AND EMPIRE ii ISRAEL AND EMPIRE A Postcolonial History of Israel and Early Judaism Leo G. Perdue and Warren Carter Edited by Coleman A. Baker LONDON • NEW DELHI • NEW YORK • SYDNEY 1 Bloomsbury T&T Clark An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Imprint previously known as T&T Clark 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com Bloomsbury, T&T Clark and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2015 © Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker, 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Authors of this work. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the authors. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: HB: 978-0-56705-409-8 PB: 978-0-56724-328-7 ePDF: 978-0-56728-051-0 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Typeset by Forthcoming Publications (www.forthpub.com) 1 Contents Abbreviations vii Preface ix Introduction: Empires, Colonies, and Postcolonial Interpretation 1 I. -

The Geologic Time Scale Is the Eon

Exploring Geologic Time Poster Illustrated Teacher's Guide #35-1145 Paper #35-1146 Laminated Background Geologic Time Scale Basics The history of the Earth covers a vast expanse of time, so scientists divide it into smaller sections that are associ- ated with particular events that have occurred in the past.The approximate time range of each time span is shown on the poster.The largest time span of the geologic time scale is the eon. It is an indefinitely long period of time that contains at least two eras. Geologic time is divided into two eons.The more ancient eon is called the Precambrian, and the more recent is the Phanerozoic. Each eon is subdivided into smaller spans called eras.The Precambrian eon is divided from most ancient into the Hadean era, Archean era, and Proterozoic era. See Figure 1. Precambrian Eon Proterozoic Era 2500 - 550 million years ago Archaean Era 3800 - 2500 million years ago Hadean Era 4600 - 3800 million years ago Figure 1. Eras of the Precambrian Eon Single-celled and simple multicelled organisms first developed during the Precambrian eon. There are many fos- sils from this time because the sea-dwelling creatures were trapped in sediments and preserved. The Phanerozoic eon is subdivided into three eras – the Paleozoic era, Mesozoic era, and Cenozoic era. An era is often divided into several smaller time spans called periods. For example, the Paleozoic era is divided into the Cambrian, Ordovician, Silurian, Devonian, Carboniferous,and Permian periods. Paleozoic Era Permian Period 300 - 250 million years ago Carboniferous Period 350 - 300 million years ago Devonian Period 400 - 350 million years ago Silurian Period 450 - 400 million years ago Ordovician Period 500 - 450 million years ago Cambrian Period 550 - 500 million years ago Figure 2. -

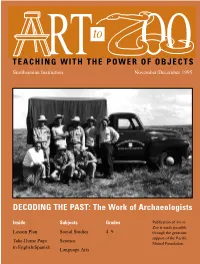

DECODING the PAST: the Work of Archaeologists

to TEACHINGRT WITH THE POWER OOOF OBJECTS Smithsonian Institution November/December 1995 DECODING THE PAST: The Work of Archaeologists Inside Subjects Grades Publication of Art to Zoo is made possible Lesson Plan Social Studies 4–9 through the generous support of the Pacific Take-Home Page Science Mutual Foundation. in English/Spanish Language Arts CONTENTS Introduction page 3 Lesson Plan Step 1 page 6 Worksheet 1 page 7 Lesson Plan Step 2 page 8 Worksheet 2 page 9 Lesson Plan Step 3 page 10 Take-Home Page page 11 Take-Home Page in Spanish page 13 Resources page 15 Art to Zoo’s purpose is to help teachers bring into their classrooms the educational power of museums and other community resources. Art to Zoo draws on the Smithsonian’s hundreds of exhibitions and programs—from art, history, and science to aviation and folklife—to create classroom- ready materials for grades four through nine. Each of the four annual issues explores a single topic through an interdisciplinary, multicultural Above photo: The layering of the soil can tell archaeologists much about the past. (Big Bend Reservoir, South Dakota) approach. The Smithsonian invites teachers to duplicate Cover photo: Smithsonian Institution archaeologists take a Art to Zoo materials for educational use. break during the River Basin Survey project, circa 1950. DECODING THE PAST: The Work of Archaeologists Whether you’re ten or one hundred years old, you have a sense of the past—the human perception of the passage of time, as recent as an hour ago or as far back as a decade ago. -

Neo-Assyrian Treaties As a Source for the Historian: Bonds of Friendship, the Vigilant Subject and the Vengeful King�S Treaty

WRITING NEO-ASSYRIAN HISTORY Sources, Problems, and Approaches Proceedings of an International Conference Held at the University of Helsinki on September 22-25, 2014 Edited by G.B. Lanfranchi, R. Mattila and R. Rollinger THE NEO-ASSYRIAN TEXT CORPUS PROJECT 2019 STATE ARCHIVES OF ASSYRIA STUDIES Published by the Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project, Helsinki in association with the Foundation for Finnish Assyriological Research Project Director Simo Parpola VOLUME XXX G.B. Lanfranchi, R. Mattila and R. Rollinger (eds.) WRITING NEO-ASSYRIAN HISTORY SOURCES, PROBLEMS, AND APPROACHES THE NEO- ASSYRIAN TEXT CORPUS PROJECT State Archives of Assyria Studies is a series of monographic studies relating to and supplementing the text editions published in the SAA series. Manuscripts are accepted in English, French and German. The responsibility for the contents of the volumes rests entirely with the authors. © 2019 by the Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project, Helsinki and the Foundation for Finnish Assyriological Research All Rights Reserved Published with the support of the Foundation for Finnish Assyriological Research Set in Times The Assyrian Royal Seal emblem drawn by Dominique Collon from original Seventh Century B.C. impressions (BM 84672 and 84677) in the British Museum Cover: Assyrian scribes recording spoils of war. Wall painting in the palace of Til-Barsip. After A. Parrot, Nineveh and Babylon (Paris, 1961), fig. 348. Typesetting by G.B. Lanfranchi Cover typography by Teemu Lipasti and Mikko Heikkinen Printed in the USA ISBN-13 978-952-10-9503-0 (Volume 30) ISSN 1235-1032 (SAAS) ISSN 1798-7431 (PFFAR) CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................. vii Giovanni Battista Lanfranchi, Raija Mattila, Robert Rollinger, Introduction .............................. -

The Philosophy and Physics of Time Travel: the Possibility of Time Travel

University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well Honors Capstone Projects Student Scholarship 2017 The Philosophy and Physics of Time Travel: The Possibility of Time Travel Ramitha Rupasinghe University of Minnesota, Morris, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.morris.umn.edu/honors Part of the Philosophy Commons, and the Physics Commons Recommended Citation Rupasinghe, Ramitha, "The Philosophy and Physics of Time Travel: The Possibility of Time Travel" (2017). Honors Capstone Projects. 1. https://digitalcommons.morris.umn.edu/honors/1 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Philosophy and Physics of Time Travel: The possibility of time travel Ramitha Rupasinghe IS 4994H - Honors Capstone Project Defense Panel – Pieranna Garavaso, Michael Korth, James Togeas University of Minnesota, Morris Spring 2017 1. Introduction Time is mysterious. Philosophers and scientists have pondered the question of what time might be for centuries and yet till this day, we don’t know what it is. Everyone talks about time, in fact, it’s the most common noun per the Oxford Dictionary. It’s in everything from history to music to culture. Despite time’s mysterious nature there are a lot of things that we can discuss in a logical manner. Time travel on the other hand is even more mysterious. -

History Vs. the Past

IN JCB an occasional newsletter of the john carter brown library History vs. the Past In an incidental remark, Virginia Woolf advised a young writer: “Nothing has really he past is an “ocean of events that once happened until you have described it.” That is T happened,” explained the renowned Pol- the essential truth. ish philosopher, Leszek Kolakowski, in re- What we witness at the jcb every day are marks delivered last year after he was awarded scholars sifting through the plenitude of the the Kluge Prize ($1 million) by the Library of recorded past, both texts and images, manu- Congress. Those past events, he said, are “re- scripts and print, to construct “history”—art constructed by us on the basis of our present history, literary history, ethnohistory, and so experience—and it is only this present experi- forth. The books they are using were earlier ence, our present reconstruction of the past, efforts to articulate something about the times, that is real, not the past as such.” about past happenings. There is, then, in fact, Kolakowski spoke the obvious truth, but he should have emphasized the selectivity of that reconstruction of elements from the past, since the infinite detail and totality of the past, as of course he knows, can never be reconstructed. The writing of history is a process of highly selective reconstruction of features of the past. Confusion occurs sometimes when we use the word “history” to mean not just historical writ- ing but also as a synonym for the entirety of past happenings. “History was made today,” some reporter somewhere probably wrote when the Boston Red Sox won a world series, but the game itself did not make history; the reporter, in writing about the game, “made” history (although prob- ably not enduring history).