1960 : the Dilemma of Adlai Stevenson Robert A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Harlan Cleveland Interviewer: Sheldon Stern Date of Interview: November 30, 1978 Location: Cambridge, Massachusetts Length: 56 Pages

Harlan Cleveland Oral History Interview—11/30/1978 Administrative Information Creator: Harlan Cleveland Interviewer: Sheldon Stern Date of Interview: November 30, 1978 Location: Cambridge, Massachusetts Length: 56 pages Biographical Note Cleveland, Assistant Secretary of State for International Organization Affairs (1961- 1965) and Ambassador to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) (1965-1969), discusses the relationship between John F. Kennedy, Adlai E. Stevenson, and Dean Rusk; Stevenson’s role as U.S. ambassador to the United Nations; the Bay of Pigs invasion; the Cuban missile crisis; and the Vietnam War, among other issues. Access Open. Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed February 21, 1990, copyright of these materials has passed to the United States Government upon the death of the interviewee. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any document from which they wish to publish. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. -

Department of State Key Officers List

United States Department of State Telephone Directory This customized report includes the following section(s): Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED) 1/17/2017 Provided by Global Information Services, A/GIS Cover UNCLASSIFIED Key Officers of Foreign Service Posts Afghanistan RSO Jan Hiemstra AID Catherine Johnson CLO Kimberly Augsburger KABUL (E) Great Massoud Road, (VoIP, US-based) 301-490-1042, Fax No working Fax, INMARSAT Tel 011-873-761-837-725, ECON Jeffrey Bowan Workweek: Saturday - Thursday 0800-1630, Website: EEO Erica Hall kabul.usembassy.gov FMO David Hilburg IMO Meredith Hiemstra Officer Name IPO Terrence Andrews DCM OMS vacant ISO Darrin Erwin AMB OMS Alma Pratt ISSO Darrin Erwin Co-CLO Hope Williams DCM/CHG Dennis W. Hearne FM Paul Schaefer Algeria HRO Dawn Scott INL John McNamara ALGIERS (E) 5, Chemin Cheikh Bachir Ibrahimi, +213 (770) 08- MGT Robert Needham 2000, Fax +213 (21) 60-7335, Workweek: Sun - Thurs 08:00-17:00, MLO/ODC COL John Beattie Website: http://algiers.usembassy.gov POL/MIL John C. Taylor Officer Name SDO/DATT COL Christian Griggs DCM OMS Sharon Rogers, TDY TREAS Tazeem Pasha AMB OMS Carolyn Murphy US REP OMS Jennifer Clemente Co-CLO Julie Baldwin AMB P. Michael McKinley FCS Nathan Seifert CG Jeffrey Lodinsky FM James Alden DCM vacant HRO Dana Al-Ebrahim PAO Terry Davidson ICITAP Darrel Hart GSO William McClure MGT Kim D'Auria-Vazira RSO Carlos Matus MLO/ODC MAJ Steve Alverson AFSA Pending OPDAT Robert Huie AID Herbie Smith POL/ECON Junaid Jay Munir CLO Anita Kainth POL/MIL Eric Plues DEA Craig M. -

White House Photographs May 8, 1976

Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library White House Photographs May 8, 1976 This database was created by Library staff and indexes all photographs taken by the Ford White House photographersrelated to this subject. Use the search capabilities in your PDF reader to locate key words within this index. Please note that clicking on the link in the “Roll #” field will display a 200 dpi JPEG image of the contact sheet (1:1 images of the 35 mm negatives). Gerald Ford is always abbreviated “GRF” in the "Names" field. If the "Geographic" field is blank, the photo was taken within the White House complex. The date on the contact sheet image is the date the roll of film was processed, not the date the photographs were taken. All photographs taken by the White House photographers are in the public domain and reproductions (600 dpi scans or photographic prints) of individual images may be purchased and used without copyright restriction. Please include the roll and frame numbers when contacting the Library staff about a specific photo (e.g., A1422-10). To view photo listings for other dates, to learn more about this project or other Library holdings, or to contact an archivist, please visit the White House Photographic Collection page View President Ford's Daily Diary (activities log) for this day Roll # Frames Tone Subject - Proper Subject - Generic Names Geographic Location Photographer A9656 7A-11A BW SecState Trip to Africa-SecState Returns from 6- standing on tarmac, in front Kissinger, Nancy Kissinger, Others, Andrews Air Force Andrews Air Thomas Nation African Tour-Airport Arrival; Chief of plane; Catto and Kissinger Military Officers, Catto Base, MD Force Base Protocol Officer Henry Catto standiang together; aircraft in background A9657 26-36 BW SecState Trip to Africa-SecState Returns from 6- HAK kissing wife; Kissinger, Nancy Kissinger, Sen. -

Stewart L. Udall Oral History Interview – JFK #1, 1/12/1970 Administrative Information

Stewart L. Udall Oral History Interview – JFK #1, 1/12/1970 Administrative Information Creator: Stewart L. Udall Interviewer: W.W. Moss Date of Interview: January 12, 1970 Length: 28 pp. Biographical Note Udall was the Secretary of the Interior for the President Kennedy and President Johnson Administrations (1961-1969). This interview focuses on Udall’s political background, his first impressions of Senator John F. Kennedy, Labor Relations of 1958, and the 1960 presidential nomination, among other issues. Access Restrictions No restrictions. Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed March 17, 1981, copyright of these materials have been assigned to the United States Government. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any document from which they wish to publish. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. The copyright law extends its protection to unpublished works from the moment of creation in a tangible form. -

Materials at the LBJ Library Pertaining to Arthur Goldberg

LYNDON BAINES JOHNSON L I B R A R Y & M U S E U M www.lbjlibrary.org March 1992 GOLDBERG, ARTHUR J. 6/9/1992 MATERIAL AT THE LBJ LIBRARY PERTAINING TO ARTHUR J. GOLDBERG INTRODUCTION Arthur J. Goldberg served as Secretary of Labor to President John F. Kennedy from January 1961 to October 1962, then as Associate Justice on the United States Supreme Court from October 1962 to July 1965. On July 26, 1965, President Lyndon Johnson appointed Goldberg to the position of United States Ambassador to the United Nations, a post he held until his resignation on April 25, 1968. This list includes the principal files in the LBJ Library that contain material on Arthur J. Goldberg. It is not definitive, however, and researchers should consult with an archivist about other potentially useful files. Those files listed below that are marked with two asterisks are unprocessed and are not currently available for research. NATIONAL SECURITY FILE (NSF) This file was the working file of President Johnson's special assistants for national security affairs, McGeorge Bundy and Walt W. Rostow. Documents in the file originated in the offices of Bundy and Rostow and their staffs, in the various executive departments and agencies, especially those having to do with foreign affairs and national defense, and in diplomatic and military posts around the world. More than half of the National Security File has been processed and opened for research. Consult the finding aid in the Reading Room or borrow a copy by mail by writing to the Supervisory Archivist, LBJ Library, 2313 Red River Street, Austin, Texas 78705. -

Argreportopt.Pdf

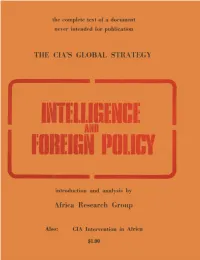

A NECESSARY INTRODUCTIQN PREFACE There are few people wi h any degree of. political literacy anywhere in the world. who have nQt heard about the CIA. Its n oriety is well deserved even if its precise functions in the service of the American Empire often isappear under a cloud of fictional images or crude conspiratorial theories. The Africa Research Gr up is now able to make available the text of a document which helps fill many of the existing ga in understanding the expanded role intelligence agellci~s play in plannin and executing f reign policy objectives. "Intelligence and Foreign Policy," as the document is titled, illumi tes the role of covert action. It enumerates the mechanisms which allow the United States t interfere, with almost routine regularity, in the internal affairs of sovereign nations through ut the world.- We are p~blishing it for many of th~ ,same reason that .American newspapers de ·ed governmel)t censorship to disclose the secret,o igins ,0 the War against the people of Indo hina. Unlike those newspapers, however, we feel the pu~lic ~as more than a "right to know"; it has the duty to struggle against the system which needs and uses the CIA. In addition to the docum nt, the second section of the pamphlet examines CIA inv~lve~ent in a specific setting: its role in the pacification of the Leftist opposition in Kenya, and its promotion of "cultural nationalism" i lother reas of Africa. The larger strategies spoken of in the document here reappear as the dail interventions of U.S. -

WISCONSIN MAGAZINE of HISTORY the State Historical Society Ofwisconsin • Vol

(ISSN 0043-6534) WISCONSIN MAGAZINE OF HISTORY The State Historical Society ofWisconsin • Vol. 75, No. 3 • Spring, 1992 fr»:g- •>. * i I'^^^^BRR' ^ 1 THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WISCONSIN H. NICHOLAS MULLER III, Director Officers FANNIE E. HICKLIN, President GERALD D. VISTE, Treasurer GLENN R. COATES, First Vice-President H. NICHOLAS MULLER III, Secretary JANE BERNHARDT, Second Vice-President THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WISCONSIN is both a state agency and a private membership organization. Founded in 1846—two years before statehood—and chartered in 1853, it is the oldest American historical society to receive continuous public funding. By statute, it is charged with collecting, advancing, and dissemi nating knowledge ofWisconsin and ofthe trans-Allegheny West The Society serves as the archive ofthe State ofWisconsin; it collects all manner of books, periodicals, maps, manuscripts, relics, newspapers, and aural and graphic materials as they relate to North America; it maintains a museum, library, and research facility in Madison as well as a statewide system of historic sites, school services, area research centers, and affiliated local societies; it administers a broad program of historic preservation; and publishes a wide variety of historical materials, both scholarly and popular. MEMBERSHIP in the Society is open to the public. Individual memhersh'ip (one per son) is $25. Senior Citizen Individual membership is $20. Family membership is $30. Senicrr Citizen Family membership is $25. Suppcrrting memhershvp is $100. Sustaining membership is $250. A Patron contributes $500 or more. Life membership (one person) is $1,000. MEMBERSHIP in the Friends of the SHSW is open to the public. -

Vietnam and the United Nations, Part 6

September 6, 1967 The Honorable Henry M. Jackson The United States Senate Senate Office BuUding Washington, D. C. near Senator Jackson: ay I enclose. for your information. rny exchange of letter 8 with Senator Stennis: Sincerely yours, HES:cc Harold E. Stassen Enclosures September 6, 1967 The Honorable Strom Thurmond The United States Senate Senate Office Building Washington. D. C. Dear Senator Thurmond: ay I enclose, for your information. my exchange of letter. with Senator Stennis. Sincerely yours, HES:cc Harold E. Sta.sen Enclosures September 6, 1967 The Honorable Jack MiUer The United States Senate Senate Office Building Washington, D. C. Deal" Senator MWer: y I enclose, for your information. my exchange of letters with Senator Stennis. Sincerely yours, HES:cc Harold E. Stusen Enclosures September 6. 1967 The Honorable Stuart Symington The United States Senate Senate Office Building Washington, D. C. Dear Senator Symington: May I enclo.e. for your information. my exchange of letters with Senator Stennis. Sincerely yours, HES:cc Harold E. Stassen Enclosures September 6. 1967 The Honorable argaret Chase Smith The United States Senate Senate Office Building Washington. D. C. Dear Senator Smith! May 1 enclose. for your information. my exchange of letters with Senator Stennis. Sincerely yours. HES:cc Harold E. Stassen Enclosures September 6. 1967 Mr. Jack Bell Associated Press Senate Pre •• Gallery Washington. D. C. Dear Jack: Herewith copies of the {ollow-up ith Senator Stennis. ith personal best wishes. Sincerely yours, HES:cc Harold E. Stassen Enclosures September 5, J967 r. Jack Bell Associated Pre.s Senate Preas Gallery The Capitol Washington, D. -

Devil's Advocate Defeated: George Ball As a True Dissenter

Devil’s Advocate Defeated: George Ball as a True Dissenter Sam Fancher It is the late summer of 1964. The South Vietnamese government is on the verge of collapse, and President Lyndon B. Johnson is considering secret plans to bomb North Vietnam. In steps Undersecretary of State George Ball. On August 29th, Ball re- ceives a phone call from his friend, reporter James Reston of the New York Times, who has read a leaked report on conditions in Saigon. He confirms with Ball that the situation is tense, and then proceeds to ask, “What about finding a way to get out of Vietnam?” to which Ball responds, “Nobody is thinking seriously about pulling out or initiating negotiations.” Then, Reston inquires, “What about a wider, Geneva- type conference?” “Unworkable,” Ball answers.1 On October 5th, how- ever, just five weeks later, Ball turns in a sixty-seven page memoran- dum annihilating the foundations of the administration’s Vietnam strategy and proposing a negotiated exit. The memo turned out to be highly prescient, anticipating nearly everything that subsequently went wrong in Vietnam. But Johnson rejected its advice and chose military escalation over a negotiated withdrawal. Why was Ball ignored? It depends on which Ball was the real George Ball: the hawk who talked to Reston or the dove who wrote the memo five weeks later. Such a dramatic change is unusual in so short a time. Some academic historians argue, therefore, that Ball must have been a hawk whose role in the administration was to play the role of dove and “devil’s advocate.” Because he was only playing a role, his memo was not taken seriously. -

Images of Inherited War Ree American Presidents in Vietnam

THE 13 DREW PER PA S Images of Inherited War ree American Presidents in Vietnam William R. Hersch Lieutenant Colonel, USAF Air University David S. Fadok, Lieutenant General, Commander and President School of Advanced Air and Space Studies Jeffrey J. Smith, Colonel, PhD, Commandant and Dean AIR UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF ADVANCED AIR AND SPACE STUDIES Images of Inherited War Three American Presidents in Vietnam William R. Hersch Lieutenant Colonel, USAF Drew Paper No. 13 Air University Press Air Force Research Institute Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama Project Editor Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jeanne K. Shamburger Hersch, William R., 1972– Cover Art, Book Design, and Illustrations Images of inherited war : three American presidents in Vietnam Daniel Armstrong / William R. Hersch, Lt. Colonel, USAF. Composition and Prepress Production pages cm. — (Drew paper, ISSN 1941-3785 ; no. 13) Nedra Looney Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-1-58566-249-4 Print Preparation and Distribution 1. Vietnam War, 1961–1975—Public opinion. 2. Vietnam War, Diane Clark 1961–1975—United States. 3. Kennedy, John F. (John Fitzgerald), 1917–1963—Public opinion. 4. Johnson, Lyndon B. (Lyndon Baines), 1908–1973—Public opinion. 5. Nixon, Richard M. (Richard Milhous), 1913–1994—Public opinion. 6. Political AIR FORCE RESEARCH INSTITUTE culture—United States—History—20th century. 7. Public opinion—United States—History—20th century. I. Title. AIR UNIVERSITY PRESS DS559.62.U6H46 2014 959.704’31–dc23 2014034552 Director and Publisher Allen G. Peck Editor in Chief Oreste M. Johnson Published by Air University Press in February 2014 Managing Editor Demorah Hayes Design and Production Manager Cheryl King Air University Press 155 N. -

Congressional Affairs

HARRY LeROY JONES, Departmental Editor Departmental Comment Congressional Affairs Activities of the First Session of the 92nd Congress Relating to Inter- nationalLaw and Foreign Relations Issues of foreign policy arising in a context of disagreement as to the relative rights and responsibilities of the Executive and Legislative branches dominated the first session of the 92nd Congress. President Nixon's domestic "New American Revolution" announced in January 1971 was all but forgotten, as the debate on the Vietnamese war went on and on. A reorganization of foreign aid and an extension of the draft also loomed prominently. According to, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee's report, made December 21 by its Sub-Committee on Security Agreements and Com- mitments Abroad, the United States has assumed "creeping com- mitments" that threaten to trap the nation in global responsibilities. The sub-committee chairman, Senator Stuart Symington (D.Mo.) stated: "The basic thrust of the report is the people's right to know what are the facts." The report summarized two years of investigation and 2,500 pages of hearings on the Philippines, Laos, Thailand, Taiwan, Japan, Okinawa, Korea, Greece, Turkey, Ethiopia, Morocco, Libya, NATO, and Spain. "Spain is a good example," the Subcommittee asserted, "of a commitment which has not only crept but which has also, in the process, generated new justifications as old ones became obsolete." Accusing the Executive Branch of using security classification "to pre- vent legitimate inquiry" by proper committees of the Senate, the report recommends that Congress undertake, on regular schedule, inquiries on foreign policy, including the political aspects of military activities: "Con- gress should take a realistic look at the authority of the President to station troops abroad and establish bases in foreign countries." Specific prior authority of the Congress should be required in both cases. -

John F. Kennedy, Ghana and the Volta River Project : a Study in American Foreign Policy Towards Neutralist Africa

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-1989 John F. Kennedy, Ghana and the Volta River project : a study in American foreign policy towards neutralist Africa. Kurt X. Metzmeier 1959- University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Metzmeier, Kurt X. 1959-, "John F. Kennedy, Ghana and the Volta River project : a study in American foreign policy towards neutralist Africa." (1989). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 967. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/967 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JOHN F. KENNEDY, GHANA AND THE \\ VOLTA RIVER PROJECT A Study in American Foreign Policy towards Neutralist Africa By Kurt X. Metzmeier B.A., Universdty of Louisville, 1982 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May 1989 JOHN F. KENNEDY, GHANA AND THE VOLTA RIVER PROJECT A Study in American Foreign Policy Towards Neutralist Africa By Kurt X. Metzmeier B.A., University of Louisville, 1982 A Thesis• Approved on April 26, 1989 (DATE) By the following Reading Committee: Thesis Director 11 ABSTRACT The emergence of an independent neutralist Africa changed the dynamics of the cold war.