Federation Peak

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CLIMBING FEDERATION PEAK, SOUTH WEST TASMANIA Macquarie (University) Mountaineering Club Trip 1972 by Barbara Cameron Smith June 5, 2014

CLIMBING FEDERATION PEAK, SOUTH WEST TASMANIA Macquarie (University) Mountaineering Club trip 1972 By Barbara Cameron Smith June 5, 2014 Our anti clockwise route towards and up Federation Peak is depicted in orange above, with the exception of our detour off the loop to climb Burgess Bluff. We subsequently camped at Pineapple Flat, scrub bashed our way to Mount Picton, and eventually walked out to Blakes Opening along an unexpectedly civilized track. Map credit: Bill Filson 7 January 1972 We packed all our gear and then went shopping. We expect to be out for 7-10 days, and after packing the necessary food and excess, the food bill tallied 26 dollars for four, quite a lot of money. We went to local camping stores and got some extra equipment, then called in to chat with a few guys who could tell us something about the walk. We repacked everything after a counter lunch in a pub and off we went. We walked quite a way out of the main street of Hobart. Greg and I started hitching and were lucky, getting a lift with a guy who was going camping himself. I guess I was rather forward but I asked him if he’d mind picking up our two friends who were on the road already. He didn’t seem to mind, so we were all driven down to Geeveston. Had a few refreshments there and left details at the police station and gear at the council chambers. It was rather late to get a lift, it being 4.30 pm, but a local housewife drove all of us a few miles out of town. -

3966 Tour Op 4Col

The Tasmanian Advantage natural and cultural features of Tasmania a resource manual aimed at developing knowledge and interpretive skills specific to Tasmania Contents 1 INTRODUCTION The aim of the manual Notesheets & how to use them Interpretation tips & useful references Minimal impact tourism 2 TASMANIA IN BRIEF Location Size Climate Population National parks Tasmania’s Wilderness World Heritage Area (WHA) Marine reserves Regional Forest Agreement (RFA) 4 INTERPRETATION AND TIPS Background What is interpretation? What is the aim of your operation? Principles of interpretation Planning to interpret Conducting your tour Research your content Manage the potential risks Evaluate your tour Commercial operators information 5 NATURAL ADVANTAGE Antarctic connection Geodiversity Marine environment Plant communities Threatened fauna species Mammals Birds Reptiles Freshwater fishes Invertebrates Fire Threats 6 HERITAGE Tasmanian Aboriginal heritage European history Convicts Whaling Pining Mining Coastal fishing Inland fishing History of the parks service History of forestry History of hydro electric power Gordon below Franklin dam controversy 6 WHAT AND WHERE: EAST & NORTHEAST National parks Reserved areas Great short walks Tasmanian trail Snippets of history What’s in a name? 7 WHAT AND WHERE: SOUTH & CENTRAL PLATEAU 8 WHAT AND WHERE: WEST & NORTHWEST 9 REFERENCES Useful references List of notesheets 10 NOTESHEETS: FAUNA Wildlife, Living with wildlife, Caring for nature, Threatened species, Threats 11 NOTESHEETS: PARKS & PLACES Parks & places, -

Characteristics of Interstate and Overseas Bushwalkers in the Arthur Ranges, South West Tasmania

CHARACTERISTICS OF INTERSTATE AND OVERSEAS BUSHWALKERS IN THE ARTHUR RANGES, SOUTH-WEST TASMANIA By Douglas A. Grubert & Lorne K. Kriwoken RESEARCH REPORT RESEARCH REPORT SERIES The primary aim of CRC Tourism's research report series is technology transfer. The reports are targeted toward both industry and government users and tourism researchers. The content of this technical report series primarily focuses on applications, but may also advance research methodology and tourism theory. The report series titles relate to CRC Tourism's research program areas. All research reports are peer reviewed by at least two external reviewers. For further information on the report series, access the CRC website [www.crctourism.com.au]. EDITORS Prof Chris Cooper University of Queensland Editor-in-Chief Prof Terry De Lacy CRC for Sustainable Tourism Chief Executive Prof Leo Jago CRC for Sustainable Tourism Director of Research National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Grubert, Douglas. Characteristics of interstate and overseas bushwalkers in the Arthur Ranges, South West Tasmania. Bibliography. ISBN 1 876685 83 2. 1. Hiking - Research - Tasmania - Arthur Range. 2. Hiking - Tasmania - Arthur Range - Statistics. 3. National parks and reserves - Public use - Tasmania - Arthur Range. I. Kriwoken, Lorne K. (Lorne Keith). II. Cooperative Research Centre for Sustainable Tourism. III. Title. 796.52209946 © 2002 Copyright CRC for Sustainable Tourism Pty Ltd All rights reserved. No parts of this report may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by means of electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Any enquiries should be directed to Brad Cox, Director of Communications or Trish O’Connor, Publications Manager to [email protected]. -

A Review of Geoconservation Values

Geoconservation Values of the TWWHA and Adjacent Areas 3.0 GEOCONSERVATION AND GEOHERITAGE VALUES OF THE TWWHA AND ADJACENT AREAS 3.1 Introduction This section provides an assessment of the geoconservation (geoheritage) values of the TWWHA, with particular emphasis on the identification of geoconservation values of World Heritage significance. This assessment is based on: • a review (Section 2.3.2) of the geoconservation values cited in the 1989 TWWHA nomination (DASETT 1989); • a review of relevant new scientific data that has become available since 1989 (Section 2.4); and: • the use of contemporary procedures for rigorous justification of geoconservation significance (see Section 2.2) in terms of the updated World Heritage Criteria (UNESCO 1999; see this report Section 2.3.3). In general, this review indicates that the major geoconservation World Heritage values of the TWWHA identified in 1989 are robust and remain valid. However, only a handful of individual sites or features in the TWWHA are considered to have World Heritage value in their own right, as physical features considered in isolation (eg, Exit Cave). In general it is the diversity, extent and inter-relationships between numerous features, sites, areas or processes that gives World Heritage significance to certain geoheritage “themes” in the TWWHA (eg, the "Ongoing Natural Geomorphic and Soil Process Systems" and “Late Cainozoic "Ice Ages" and Climate Change Record” themes). This "wholistic" principle under-pinned the 1989 TWWHA nomination (DASETT 1989, p. 27; see this report Section 2.3.2), and is strongly supported by the present review (see discussion and justification of this principle in Section 2.2). -

Coastal Erosion Reveals a Potentially Unique Oligocene and Possible Periglacial Sequence at Present-Day Sea Level in Port Davey, Remote South-West Tasmania

Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania, Volume 148, 2014 43 COASTAL EROSION REVEALS A POTENTIALLY UNIQUE OLIGOCENE AND POSSIBLE PERIGLACIAL SEQUENCE AT PRESENT-DAY SEA LEVEL IN PORT DAVEY, REMOTE SOUTH-WEST TASMANIA by Mike Macphail, Chris Sharples, David Bowman, Sam Wood & Simon Haberle (with two text-figures, five plates and two tables) Macphail, M., Sharples, C., Bowman, D., Wood, S. & Haberle, S. 2014 (19:xii): Coastal erosion reveals a potentially unique Oligocene and possible periglacial sequence at present-day sea level in Port Davey, remote South-West Tasmania. Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania 148: 43–59. https://doi.org/10.26749/rstpp.148.43 ISSN 0080-4703 Department of Archaeology & Natural History, College of Asia and the Pacific, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 0200, Australia (MM*, SH); School of Geography & Environmental Studies, Faculty of Science, Engineering & Technology, University of Tasmania, Hobart 7001, Tasmania, Australia (CS); School of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science, Engineering & Technology, University of Tasmania, Hobart 7001, Tasmania, Australia (DB, SW). *Author for correspondence. Email: [email protected] Cut-back of a sea-cliff at Hannant Inlet in remote South-West Tasmania has exposed Oligocene clays buried under Late Pleistocene “collu- vium” from which abundant wood fragments protrude. The two units are separated by a transitional interval defined by mixed Oligocene and Pleistocene microfloras. Microfloras preserved in situ in the clay provide a link between floras in Tasmania and other Southern Hemisphere landmasses following onset of major glaciation in East Antarctica during the Eocene-Oligocene transition (c. 34 Ma). -

Reimagining the Visitor Experience of Tasmania's Wilderness World

Reimagining the Visitor Experience of Tasmania’s Wilderness World Heritage Area Ecotourism Investment Profile Reimagining the Visitor Experience of Tasmania’s Wilderness World Heritage Area: Ecotourism Investment Profile This report was commissioned by Tourism Industry Council Tasmania and the Cradle Coast Authority, in partnership with the Tasmanian Government through Tourism Tasmania and the Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service. This report is co-funded by the Australian Government under the Tourism Industry Regional Development Fund Grants Programme. This report has been prepared by EC3 Global, TRC Tourism and Tourism Industry Council Tasmania. Date prepared: June 2014 Design by Halibut Creative Collective. Disclaimer The information and recommendations provided in this report are made on the basis of information available at the time of preparation. While all care has been taken to check and validate material presented in this report, independent research should be undertaken before any action or decision is taken on the basis of material contained in this report. This report does not seek to provide any assurance of project viability and EC3 Global, TRC Tourism and Tourism Industry Council Tasmania accept no liability for decisions made or the information provided in this report. Cover photo: Huon Pine Walk Corinna The Tarkine - Rob Burnett & Tourism Tasmania Contents Background...............................................................2 Reimagining the Visitor Experience of the TWWHA .................................................................5 -

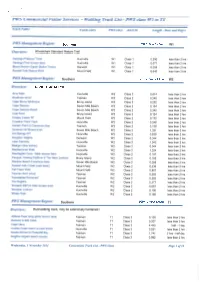

Walking Track List - PWS Class Wl to T4

PWS Commercial Visitor Services - Walking Track List - PWS class Wl to T4 Track Name FieldCentre PWS class AS2156 Length - Kms and Days PWS Management Region: Southern PWS Track Class: VV1 Overview: Wheelchair Standard Nature Trail Hastings Platypus Track Huonville W1 Class 1 0.290 less than 2 hrs Hastings Pool access track Huonville W1 Class 1 0.077 less than 2 hrs Mount Nelson Signal Station Tracks Derwent W1 Class 1 0.059 less than 2 hrs Russell Falls Nature Walk Mount Field W1 Class 1 0.649 less than 2 hrs PWS Management Region: Southern PWS Track Class: W2 Overview: Standard Nature Trail Arve Falls Huonville W2 Class 2 0.614 less than 2 hrs Blowhole circuit Tasman W2 Class 2 0.248 less than 2 hrs Cape Bruny lighthouse Bruny Island W2 Class 2 0.252 less than 2 hrs Cape Deslacs Seven Mile Beach W2 Class 2 0.154 less than 2 hrs Cape Deslacs Beach Seven Mile Beach W2 Class 2 0.345 less than 2 hrs Coal Point Bruny Island W2 Class 2 0.124 less than 2 hrs Creepy Crawly NT Mount Field W2 Class 2 0.175 less than 2 hrs Crowther Point Track Huonville W2 Class 2 0.248 less than 2 hrs Garden Point to Carnarvon Bay Tasman W2 Class 2 3.138 less than 2 hrs Gordons Hill fitness track Seven Mile Beach W2 Class 2 1.331 less than 2 hrs Hot Springs NT Huonville W2 Class 2 0.839 less than 2 hrs Kingston Heights Derwent W2 Class 2 0.344 less than 2 hrs Lake Osbome Huonville W2 Class 2 1.042 less than 2 hrs Maingon Bay lookout Tasman W2 Class 2 0.044 less than 2 hrs Needwonnee Walk Huonville W2 Class 2 1.324 less than 2 hrs Newdegate Cave - Main access -

Recent Wildfires in the Tasmanian Wilderness

Recent wildfires in the Tasmanian Wilderness The 2016 and 2019 Tasmanian wildfires burnt upwind of the most important Gondwanan refuges that remain - Mt Anne, Mt Bobs, Federation Peak and the Eastern Arthurs, New River headwaters, the Du Cane Range, the Walls of Jerusalem, Mt Read, the Tyndall Range, the lower Gordon River and the entire Tarkine rainforest (Huskisson River in the south and the Rapid River in the north). Aerial documentation of the south-eastern part of the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area (TWWHA) in March 2019 shows that fire damage to sensitive vegetation, although not wholly catastrophic, was extensive and locally extremely severe. For many areas the consequences will be permanent. A small selection of images from the flight is included below. Of even greater concern than the damage done, however, was that, with uncontrolled fire widespread through the landscape in 2016 and 2019, a brief period of severe or catastrophic fire conditions would have obliterated Tasmania’s most important stands of Gondwanic vegetation. In hot, dry, windy conditions rainforest does burn – the Southern Ranges, Mt Picton, the Raglan Range, Frenchmans Cap, Mt Murchison, Algonkian Mountain, the upper Jane River, the Meredith Range and many other places bear grim testament to that. The effects of climate change, combined with the absence of an effective means of immediately suppressing remote wildfires, pose a catastrophic threat to irreplaceable Gondwanan flora. This vegetation forms a major component of the Outstanding Universal Value of the TWWHA. Important tracts of these ancient life forms also occur outside the TWWHA. Climate change is creating unprecedented levels of dry-lightning strikes and resultant wildfires in the Tasmanian wilderness. -

FROM CAPE to CAPE Tasmania's South Coast Track Richard Bennett

FROM CAPE TO CAPE Tasmania’s South Coast Track Richard Bennett FROM CAPE TO CAPE | Richard Bennett 1 FOREWORD From Cape to Cape presents a portrait in both photographs and Through adventure and exploration, Richard’s photography words of a unique and special place. It has been brought to life in embodies his joy of the natural world, whether it is by tackling perpetuity by Richard Bennett through his ability to capture the true the high seas, scaling mountains, trekking through valleys or just essence of the region through his vibrant photography and insightful camping out. His thoughtful contemplation, expressed in his observations. images and words, delight and inspire. The Southern Transit – South West Cape to South East Cape It has also been my privilege to share in many of these adventures. of Tasmania – concentrates all that is captivating and inspiring about the geomorphology and botanical richness of the Southern I first met Richard in the mid-1980s when I was Tasmanian wilderness. contemplating taking on what is known by many as the This portrait is a small but important step in managing the ultimate bush walk, Federation Peak, in the heart of the Richard with Stuart McGregor at Scotts Peak after a tough wet trip to the Western Arthurs. encroaching footprint of man. Critically, it provides a snapshot in time to assist in the preservation of this extraordinary place for Tasmanian Southwest wilderness region. I’d heard that future generations. Through its pages, it delivers vicarious access and few, if any, had visited the area or knew more about it than understanding, permitting participation and personal experience. -

Tasmanian Overland

Tasmanian Overland J GR HARDING (Plates 41-44) As Earth's wild places contract, so have lands once reviled become our new adventure playgrounds. Such has been the experience ofTasmania, which first intruded upon the European conscious ness with Abel Tasman's discovery in 1642 - 128 years before Captain Cook's Australian landfall. Christened by Tasman Van Diemen's Land, its geography remained a mystery until Flinders' circumnavigation in 1799 which established it as an island rather than an appendage of the mainland. Four years later the first settlers arrived and starved. For the next 50 years of the 19th century, Van Diemen's Land became notorious as the principal penal settlement for Britain's transported convicts. In convict lore this was the Fatal Shore, the land of white slavery, and 'to plough Van Diemen's Land' argot for a convict's life of retribution. When transportation was finally abolished in 1853 and the name Tasmania substituted for Van Diemen's Land, the systemized brutality which had characterized the white man's life-style had been transmitted into a campaign of genocide against the Aborigines. Within 45 years of British settlement, the dreamtime had turned nightmare and primitive man had been exterminated from the land he had inhabited for millennia. For many years, little was written or read of Tasmania's 19th-century history; but as time shades and perceptions change, the convict stain has been expunged and to modern visitors the reputation of Victorian Tasmania would be incomprehensible. In the island continent of Australia, the flattest and driest on earth, whose predominant physical characteristic is inconspicuousness, this offshore isle with abundant rainfall, forests and mountains is almost unique in its display of genuinely dramatic scenery. -

FLY NEIGHBOURLY ADVICE TASMANIAN WORLD HERITAGE AREA and MT FIELD NATIONAL PARK 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1. the Tasmanian Wildernes

FLY NEIGHBOURLY ADVICE TASMANIAN WORLD HERITAGE AREA AND MT FIELD NATIONAL PARK 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1. The Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area (WHA) and Mt Field National Park area are administered by the Tasmania Parks and Wildlife Service (TPWS), Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment. The WHA contains a number of Sensitive Areas (SAs). 1.2. The aim of Fly Neighbourly Advice (FNA) is to promote the harmonious relationship between aviation activities and environmental and conservation interests. 2. FLY NEIGHBOURLY ADVICE 2.1. There is an understanding between locally-based scenic flight and charter operators and the TPWS to operate in the WHA and Mt Field area in an agreed responsible manner. Other pilots undertaking sightseeing flights in the WHA or Mt Field area should obtain information on FNA areas, tracking details, operating altitudes, and specific areas to be avoided from: The Director Tasmania Parks and Wildlife Service Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment 134 Macquarie TAS HOBART TAS 7000 (contact officer: Planning Officer, World Heritage Area Ph: 03 6165 4261 Fax: 03 6224 0884 2.2. Advice on operating in the WHA and Mt Field area is also available from most flying schools and charter operators based at Cambridge, Launceston, Devonport, Wynyard, and Strahan. 2.3. The FNA area is approximately bounded by the following (refer WAC 3556 – Tasmania): Commencing South of Deloraine at Meander, then Miena – Derwent Bridge – Wayatinah – Westerway – Whale Head – then coastal to Low Rocky Point – Mt Sorell – Mayday Mountain – Meander. 2.4. The Sensitive Areas (SAs) are: Cradle Valley, Traveller Range, Mt Ossa to Mt Rufus, Frenchmans Cap, Mt Anne Lake Judd area, Mt Orion and Arthur Range, and Federation Peak. -

Read Competition Entries

Far South Future Ideas Competition - Entries farsouthfuture.org No 1 Lyn Martinez No 2—Sandra Garland Lots of "Keep the South Pub on Hope Island. That's where the Wild" signs, each original pub was and locals had to row featuring a local bird, out to it! Now you'd need staff and a mammal, fish or ferry driver! Jobs!!!! If the pub sold the BEST seafood, it'd be an iconic flowering plant species. destination No 3 Caroline Amos No 4 Caroline Amos All the years I lived there I Imagine a restaurant ON wished there was a tourist the bay a la jetty style! boat or dinghy hire for bay One of THE best views in trips. Olive May did a good Tasmania job for years but there is room for so much more now! No 5 Paula Sheppy As many successful tourist communities do, we need to have a brand or image ie Geeveston with wood, Byron Bay with bohemian, Cygnet with folk, Margaret River with wine etc etc. As it has massive opportunity, suggest ours is CLASSY 'bohemian'; boho, gypset, multicultural, nature focused, natural, adventurous, laid back, earthy, unconventional, free spirited, educational, etc We need a classy, laid back, cosy fire placed, 'boho'ish' pub/restaurant that offers a point of difference & is worth travelling especially to Dover for. It's range of local spirits, ciders, wines? Food only from Huon produce? Guest chefs?mulled wine for winters? A festival we are identified with because we're the only ones that do it; thats where the boho or gypsy theme is important.