General Range and Abundance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

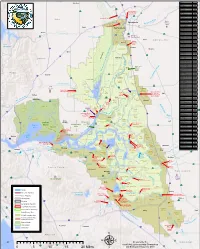

0 5 10 15 20 Miles Μ and Statewide Resources Office

Woodland RD Name RD Number Atlas Tract 2126 5 !"#$ Bacon Island 2028 !"#$80 Bethel Island BIMID Bishop Tract 2042 16 ·|}þ Bixler Tract 2121 Lovdal Boggs Tract 0404 ·|}þ113 District Sacramento River at I Street Bridge Bouldin Island 0756 80 Gaging Station )*+,- Brack Tract 2033 Bradford Island 2059 ·|}þ160 Brannan-Andrus BALMD Lovdal 50 Byron Tract 0800 Sacramento Weir District ¤£ r Cache Haas Area 2098 Y o l o ive Canal Ranch 2086 R Mather Can-Can/Greenhead 2139 Sacramento ican mer Air Force Chadbourne 2034 A Base Coney Island 2117 Port of Dead Horse Island 2111 Sacramento ¤£50 Davis !"#$80 Denverton Slough 2134 West Sacramento Drexler Tract Drexler Dutch Slough 2137 West Egbert Tract 0536 Winters Sacramento Ehrheardt Club 0813 Putah Creek ·|}þ160 ·|}þ16 Empire Tract 2029 ·|}þ84 Fabian Tract 0773 Sacramento Fay Island 2113 ·|}þ128 South Fork Putah Creek Executive Airport Frost Lake 2129 haven s Lake Green d n Glanville 1002 a l r Florin e h Glide District 0765 t S a c r a m e n t o e N Glide EBMUD Grand Island 0003 District Pocket Freeport Grizzly West 2136 Lake Intake Hastings Tract 2060 l Holland Tract 2025 Berryessa e n Holt Station 2116 n Freeport 505 h Honker Bay 2130 %&'( a g strict Elk Grove u Lisbon Di Hotchkiss Tract 0799 h lo S C Jersey Island 0830 Babe l Dixon p s i Kasson District 2085 s h a King Island 2044 S p Libby Mcneil 0369 y r !"#$5 ·|}þ99 B e !"#$80 t Liberty Island 2093 o l a Lisbon District 0307 o Clarksburg Y W l a Little Egbert Tract 2084 S o l a n o n p a r C Little Holland Tract 2120 e in e a e M Little Mandeville -

Yellow-Crowned Night-Heron Nyctanassa Violacea

Yellow-crowned Night-Heron Nyctanassa violacea Bob Moul Photo CURRENT STATUS: In Pennsylvania, the yellow-crowned night-heron is listed as state endangered and protected under the Game and Wildlife Code. Nationally, they are not listed as an endangered or threat- ened species. All migratory birds are protected under the federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. POPULATION TREND: Yellow-crowned night-herons (Nyctanassa violacea) are one of the state’s rarest nesting birds). They are rare, regular visitors or residents in the Piedmont region of southeastern Penn- sylvania (all or parts of Bucks, Northampton, Lehigh, Berks, Lebanon, Lancaster, Dauphin, York, Adams and Cumberland counties), where they breed locally. In the coastal plain area along the Delaware River near Philadelphia, they are rare, irregular visitors. They are accidental visitors elsewhere in the state, particularly in late summer following the breeding season. Currently, the only known breeding sites are in Cumberland, Dauphin and York counties. They nest singly and in loose colonies regularly along Conodo- quinet Creek. A few yellow-crowned night-herons also nest on private property in an urban setting in Dauphin County and at Kiwanis Lake in York. Nests were once also found along Conestoga and Little Conestoga creeks in Lancaster County. Surveys in the 1990s counted not more than eight to 12 nests in any year in the state. Yellow-crowned night-herons were first listed as threat- ened species in 1990 because of their limited popula- tion and restricted range. They were downgraded to endangered in 1999 because of their small and vulner- able population. IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS: Adults are me- dium-sized, 22 to 28 inches in length from bill tip to tail tip, gray with a black head and whitish cheek patch and crown. -

TYPICAL VALLEY INDIAN HOMES Vol. 2 No. 11 YUBA CITY, CALIFORNIA

Vol. 2 No. 11 YUBA CITY, CALIFORNIA OCTOBER 17 1961 TYPICAL VALLEY INDIAN HOMES SUTTER COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY FALL MEETING OCTOBER 17, 1961 TUESDAY EVENING — 8 P.M. PLACE: Board of Supervisors Chambers County Office Building, 2nd Street PRESIDENT: Mrs. Florence Arritt PROGRAM CHAIRMAN: Randolph Schnabel PROGRAM SPEAKER: Waddell F. Smith President, National Pony Express Centennial Association TOPIC: The History of the Pony Express and Its Centennial BOARD OF DIRECTORS MINUTES October 5, 1961 The Board of Directors of Sutter County Historical Society met in regular session October 5, 1961 at 7:30 P.M. in the office of the County Superintendent. The meeting was called to order by Vice President, Mrs. Ida Littlejohn in the absence of the president, Mrs. Florence Arritt. Mrs. Arritt is on her vacation traveling in the southwest and visiting many spots of historic interest such as Tombstone, Arizona. The minutes of the July Board meeting and regular meeting were read and approved. The treasurer reported cash in the bank $737.33. Film Fund $447.00 and general fund $290.33. Mr. Ramey reported a membership of 111. Fifteen new members were secured at the county fair booth. The following bills were approved for payment: Valley Print Shop — Membership Cards, Stationery $41.70. County of Sutter — Bulletin pictures $6.20. Earl Ramey — Postage $3.50. Program Chairman, Randolph Schnabel reported the program had already been arranged for the annual dinner meeting in January. Mrs. Gibson presented an invitation to the Sutter County Historical Society to en- tertain the Symposium of Historical Societies of Northern California and Southern Oregon in the fall of 1962. -

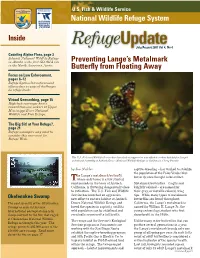

Refuge Update, I Noted That Most Important, We Have the Finest Mission and Conservation Values

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service National Wildlife Refuge System Inside RefugeUpdate July/August 2007 Vol 4, No 4 Counting Alpine Flora, page 3 Selawik National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska is the first GLORIA site Preventing Lange’s Metalmark in the North American Arctic. Butterfly from Floating Away Focus on Law Enforcement, pages 8–12 Refuge System law enforcement officers face a range of challenges on refuge lands. Virtual Geocaching, page 15 High-tech scavenger hunts reward treasure seekers at Upper Mississippi River National Wildlife and Fish Refuge. The Big Sit! at Your Refuge?, page 21 Refuge managers may want to consider this new event for Refuge Week. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has launched an aggressive new effort to restore habitat for Lange’s metalmark butterfly at Antioch Dunes National Wildlife Refuge in California. (Jerry Powell) by Jim Nickles captive-breeding – has worked to stabilize the population of the Palos Verdes blue he Lange’s metalmark butterfly, butterfly, once thought to be extinct. Twhose only home is a few stunted sand mounds in the town of Antioch, Metalmark butterflies – fragile and California, is fluttering dangerously close brightly colored – are named for to extinction. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife their grey, or metallic-colored, wing Service has launched an aggressive tips. While many types of metalmark Okefenokee Swamp new effort to restore habitat at Antioch butterflies are found throughout The cool serenity of the Okefenokee Dunes National Wildlife Refuge and California, the Lange’s metalmark is Swamp as seen in this new breed the species in captivity until its named for William H. -

Desilva Island

SUISUN BAY 139 SUISUN BAY 140 SUISUN BAY SUISUN BAY Located immediately downstream of the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers, Suisun Bay is the largest contiguous wetland area in the San Francisco Bay region. Suisun Bay is a dynamic, transitional zone between the freshwater input of the Central Valley rivers and the tidal influence of the upper San Francisco Estuary. This area supports a substantial number of nesting herons and egrets, including three of the largest colonies in the region. Although suburban development is rampant along the nearby Interstate 80 corridor to the north, most of the Suisun Bay area is protected from heavy development by the California Department of Fish and Game and a number of private duck clubs. Black- Active Great crowned or year Site Blue Great Snowy Night- Cattle last # Colony Site Heron Egret Egret Heron Egret County active Page 501 Bohannon Solano Active 142 502 Campbell Ranch Solano Active 143 503 Cordelia Road Solano 1998 145 504 Gold Hill Solano Active 146 505 Green Valley Road Solano Active 148 506 Hidden Cove Solano Active 149 507 Joice Island Solano 1994 150 508 Joice Island Annex Solano Active 151 509 Sherman Lake Sacramento Active 152 510 Simmons Island Solano 1994 153 511 Spoonbill Solano Active 154 512 Tree Slough Solano Active 155 513 Volanti Solano Active 156 514 Wheeler Island Solano Active 157 SUISUN BAY 141 142 SUISUN BAY Bohannon Great Blue Herons and Great Egrets nest in a grove of eucalyptus trees on a levee in Cross Slough, about 1.8 km east of Beldons Landing. -

Table of Contents Executive Summary

MARCH 2012 SACRAMENTO VALLEY WATER QUALITY COALITION Monitoring and Reporting Program Plan Annual Monitoring Report 2011 Prepared by: LARRY WALKER ASSOCIATES Table of Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... v Summary of Monitoring Program ............................................................................................... v Management Practices and Actions Taken ................................................................................ vi Conclusions and Recommendations ......................................................................................... vii Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 Description of the Watershed ...................................................................................................... 3 Monitoring Objectives .................................................................................................................. 4 Sampling Site Descriptions .......................................................................................................... 6 Sampling Site Locations and Land Uses .................................................................................... 7 Site Descriptions ......................................................................................................................... 9 Butte/Yuba/Sutter Subwatershed ........................................................................................... -

OBSERVATIONS on a GREAT EGRET Ardea Alba and NANKEEN NIGHT HERON Nycticorax Caledonicus COLONY at the PERTH ZOO, WESTERN AUSTRALIA

Corella, 2004, 28(3): 82-86 OBSERVATIONS ON A GREAT EGRET Ardea alba AND NANKEEN NIGHT HERON Nycticorax caledonicus COLONY AT THE PERTH ZOO, WESTERN AUSTRALIA ROBYN L. PHILLIMORE' and HARRY F. RECHER2 'School of Natural Sciences, Edith Cowan University, Joondalup, Western Australia, Australia 6027 email: [email protected]: [email protected] 'Corresponding author. Present address: P.O. Box 154, Brooklyn, New South Wales, Australia 2083 Received: I I Augusr 2003 A colony of Great Egrets Ardea alba and Nankeen Night Herons Nycticorax caledonicus has existed at the Perth Zoo, Western Australia for over 25 years. The colony of egrets is one of very few in the region and hence is significant for the conservation and management of Great Egrets in Western Australia. From 1996 to 1998, surveys were conducted to determine the number of breeding pairs, clutch size, breeding success, and nest site selection of birds in the colony. Most observations were ground based, but a 30-metre cherry picker was used to inspect nests and determine clutch size. One hundred and thirty night heron and 49 egret nests were found in 1996; 92 night heron and 41 egret nests in 1997; and, 153 night heron and 36 egret nests in 1998. Nesting commenced in September, with peak numbers in early November. Both species nested in tall trees well above zoo visitors and animals. Egrets nested only in pines, whereas night herons nested mainly in figs. Great Egrets had an average clutch size of 2.6-2.7 by early November compared with a clutch of 1.6-1.8 for Nankeen Night Herons. -

Westside-San Joaquin Integrated Regional Water Management Plan January 2019

San Luis & Delta-Mendota Water Authority 2019 Westside-San Joaquin Integrated Regional Water Management Plan January 2019 Prepared by: The 2019 Westside-San Joaquin Integrated Regional Water Management Plan was funded in part under the Water Quality, Supply, and Infrastructure Improvement Act of 2014 (Proposition 1), administered by the State of California, Department of Water Resources. 2019 Westside-San Joaquin Integrated Regional Water Management Plan Table of Contents Final Table of Contents Chapter 1 Governance ............................................................................................................................ 1-1 1.1 Regional Water Management Group ............................................................................................ 1-1 1.2 History of IRWM Planning ............................................................................................................. 1-4 1.3 Governance ................................................................................................................................... 1-5 1.4 Coordination ................................................................................................................................. 1-8 1.5 WSJ IRWMP Adoption, Interim Changes, and Future Updates .................................................. 1-11 Chapter 2 Region Description ................................................................................................................. 2-1 2.1 IRWM Regional Boundary ............................................................................................................ -

Nesting Populations of California and Ring-Billed Gulls in California

WESTERN BIR Volume 31, Number 3, 2000 NESTING POPULATIONS OF CLwO AND RING-BI--F-r GULLS IN CALIFORNIA: RECENT SURVEYS AND HISTORICAL STATUS W. DAVID SHUFORD, Point Reyes Bird Observatory(PRBO), 4990 Shoreline Highway, StinsonBeach, California94970 THOMAS P. RYAN, San FranciscoBay Bird Observatory(SFBBO), P.O. Box 247, 1290 Hope Street,Alviso, California 95002 ABSTRACT: Statewidesurveys from 1994 to 1997 revealed33,125 to 39,678 breedingpairs of CaliforniaGulls and at least9611 to 12,660 pairsof Ring-billed Gullsin California.Gulls nested at 12 inland sitesand in San FranciscoBay. The Mono Lake colonywas by far the largestof the CaliforniaGull, holding 70% to 80% of the statepopulation, followed by SanFrancisco Bay with 11% to 14%. ButteValley WildlifeArea, Clear Lake NationalWildlife Refuge, and Honey Lake WildlifeArea were the only othersites that heldover 1000 pairsof CaliforniaGulls. In mostyears, Butte Valley, Clear Lake, Big Sage Reservoir,and Honey Lake togetherheld over 98% of the state'sbreeding Ring-billed Gulls; Goose Lake held9% in 1997. Muchof the historicalrecord of gullcolonies consists of estimatestoo roughfor assessmentof populationtrends. Nevertheless, California Gulls, at least,have increased substantially in recentdecades, driven largely by trendsat Mono Lake and San FranciscoBay (first colonizedin 1980). Irregularoccupancy of some locationsreflects the changing suitabilityof nestingsites with fluctuatingwater levels.In 1994, low water at six sites allowedcoyotes access to nestingcolonies, and resultingpredation appeared to reducenesting success greatly at threesites. Nesting islands secure from predators and humandisturbance are nestinggulls' greatest need. Conover(1983) compileddata suggestingthat breedingpopulations of Ring-billed(Larus delawarensis)and California(Larus californicus)gulls haveincreased greafiy in the Westin recentdecades. Detailed assessments of populationstatus and trends of these speciesin individualwestern states, however,have been publishedonly for Washington(Conover et al. -

Suisun Marsh Protection Plan Map (PDF)

Proposed County Parks (Hill Slough, Fairfield Beldon’s Landing) Develop passive recreation facilities compatible with Marsh protection (e.g. fishing, picnicking, hiking, nature study.) Boat launching ramp may be constructed Suis nu at Beldon’s Landing. City Suisun Marsh 8 0 etaterstnI 80 a Protection Plan Map flHighway 12 San Francisco Bay Conservation (6) b .J ' and Development Commission I Denverton (7) I December 1976 ) I ~4 Slough Thomasson Shiloh Primary Management Area danyor, Potrero Hills ':__. .---) ... .. ... ~ . _,,. - (8) Secondary Management Area ~ ,. .,,,, Denverton ,,a !\.:r ~ Water-Related Industry Reserve Area c Beldon’s BRADMOOR ISLAND Slough (5) Landing t +{larl!✓' Road Boundary of Wildlife Areas and (9) Ecological Reserves Little I Honker (1) Grizzly Island Unit (9) Bay (2) Crescent Unit (4) Montezuma Slough (3) Island Slough Unit JOICE ISLAND (3) r (4) Joice Island Unit (5) Rush Ranch National Estuarine (10) Ecological Reserve Kirby Hill (6) Hill Slough Wildlife Area Suisun (7) Peytonia Slough Ecological Reserve (8) Grey Goose Unit GRIZZLY ISLAND (2) GRIZZLY ISLAND (9) Gold Hills Unit (10) Garibaldi Unit (11) West Family Unit (12) Goodyear Slough Unit Benicia Area Recommended for Aquisition a. Lawler Property I (11) Hills b. Bryan Property . ~-/--,~ c. Smith Property ,,-:. ...__.. ,, \ 1 Collinsville: Reserve seasonal marshes and Benicia Hills lowland grasslands for their Amended 2011 Grizzly Bay intrinsic value to marsh wildlife and Steep slopes with high landslide and soil to act as the buffer between the erosion potentials. Active fault location. Land (1) Marsh and any future water-related Collinsville Road use practices should be controlled to prevent uses to the east. -

Volcanic Legacy

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Pacifi c Southwest Region VOLCANIC LEGACY March 2012 SCENIC BYWAY ALL AMERICAN ROAD Interpretive Plan For portions through Lassen National Forest, Lassen Volcanic National Park, Klamath Basin National Wildlife Refuge Complex, Tule Lake, Lava Beds National Monument and World War II Valor in the Pacific National Monument 2 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................4 Background Information ........................................................................................................................4 Management Opportunities ....................................................................................................................5 Planning Assumptions .............................................................................................................................6 BYWAY GOALS AND OBJECTIVES ......................................................................................................7 Management Goals ..................................................................................................................................7 Management Objectives ..........................................................................................................................7 Visitor Experience Goals ........................................................................................................................7 Visitor -

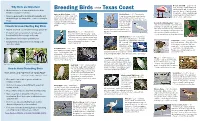

Breeding Birds of the Texas Coast

Roseate Spoonbill • L 32”• Uncom- Why Birds are Important of the mon, declining • Unmistakable pale Breeding Birds Texas Coast pink wading bird with a long bill end- • Bird abundance is an important indicator of the ing in flat “spoon”• Nests on islands health of coastal ecosystems in vegetation • Wades slowly through American White Pelican • L 62” Reddish Egret • L 30”• Threatened in water, sweeping touch-sensitive bill •Common, increasing • Large, white • Revenue generated by hunting, photography, and Texas, decreasing • Dark morph has slate- side to side in search of prey birdwatching helps support the coastal economy in bird with black flight feathers and gray body with reddish breast, neck, and Chuck Tague bright yellow bill and pouch • Nests Texas head; white morph completely white – both in groups on islands with sparse have pink bill with Black-bellied Whistling-Duck vegetation • Preys on small fish in black tip; shaggy- • L 21”• Lo- groups looking plumage cally common, increasing • Goose-like duck Threats to Island-Nesting Bay Birds Chuck Tague with long neck and pink legs, pinkish-red bill, Greg Lavaty • Nests in mixed- species colonies in low vegetation or on black belly, and white eye-ring • Nests in tree • Habitat loss from erosion and wetland degradation cavities • Occasionally nests in mesquite and Brown Pelican • L 51”• Endangered in ground • Uses quick, erratic movements to • Predators such as raccoons, feral hogs, and stir up prey Chuck Tague other woody vegetation on bay islands Texas, but common and increasing • Large