Paul Van Ostaijen, the Poet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OCTOBER 1960 • • R St Rs (Conthiued Fi.·Om Page 1) Some :Sources in 1959 to 1960 ; Ary Increases for the Business

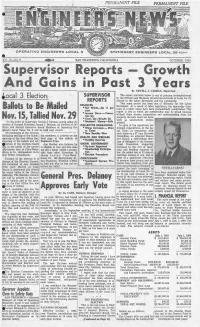

•.' _, -PERMANENT FILE '•' STATIONARY. ~ ENGfNEERS. ·. '· ... .·. -~· - .. OCTOBER,"1960 • " ~- ~- .,,.,. " J ' • •• r • • '•Ort ~ - r • :• s• "'• Past. -~ .' . --· \! . By NEWELL J. · CA~MAN, Superf isor : ·, io~aL B< Election;,, .·· ·. ;: .c. " , .' SUPElR.V.ISOR TM report-. unfolded ~ below is -~one ::. of .genuine .· accorriplfshmerit : by the Officers and Members toward improvement ·oftoc~l :N·o. 3's - .. REPORTS -~ st~tti:i-e iii: the LabOr Movement and :the community. This same p~dod _has been one of difficulty _·::1\ . :.- ~a~:-:::·-~- ·t· .. _,;·_··;_··· o~/·.:··· a-- ···- e:· < ~_:: ·· a ·ctlle:-=- .l -.-i·. · ;FiNANCES: · .. for the--Laj)or ... _. :- .. ·. ~ __1, ...:- .~ ~. '·. /: u t' Movement: As a result of labor legislation, the day-to;.day £:unc :.ye · ~q~·t W:~rt,h~Op' ll , per tions of a. labor union . · · c;ent have been.. tremendously complicated .. This · . .· .. • · . · · report is one in which · -•Income Down ;.... .Protec:- the membership m<~y be· proud because . -tici'n ·.up,·. · · · withoqt .the~r sincere --cooperation and understanding from the maj~.r,:ity tb,e task could not h<~ up-.;-:Resul!:s.Up _ve •• . Mo•~ " t5~·. l'alliid ·: Nov.,• 2~ -.>•_Cost~ '. been·· · so suec~ssfully · acc'oni- ()n the ord~i: ~ of S_up~~vis.or New ,eli. '"J~ . C~rn~a:n.; a_cting unde;, di · . • Members: , Moriey~Safe plished. · · . , r.ectlon' Qf-Ge)l'eralPresidell,t Joseph JhD_elaney~ an'electlori of' ·cott~ctrve aA.fiG~INI;i\iG - . In spite. of the significant'" ad~ · fleers and -D1§tricf Executive ·J.3oard ·.Memb€rs .of Operating . · ··wage: Increases - 'More 'd'itional expenditures of 'the1' Lo giiie$rs :· LCic<U Union ·· N:o: 3 :will b.e li~la .:ne:xtrnonth . -

Thèse Et Mémoire

Université de Montréal Survivance 101 : Community ou l’art de traverser la mutation du paysage télévisuel contemporain Par Frédérique Khazoom Département d’histoire de l’art et d’études cinématographiques, Université de Montréal, Faculté des arts et des sciences Mémoire présenté en vue de l’obtention du grade de Maîtrise ès arts en Maîtrise en cinéma, option Cheminement international Décembre 2019 © Frédérique Khazoom, 2019 Université de Montréal Département d’histoire de l’art et d’études cinématographiques Ce mémoire intitulé Survivance 101 : Community ou l’art de traverser la mutation du paysage télévisuel contemporain Présenté par Frédérique Khazoom A été évalué par un jury composé des personnes suivantes Zaira Zarza Président-rapporteur Marta Boni Directeur de recherche Stéfany Boisvert Membre du jury Résumé Lors des années 2000, le paysage télévisuel américain a été profondément bouleversé par l’arrivée d’Internet. Que ce soit dans sa production, sa création ou sa réception, l’évolution rapide des technologies numériques et l’apparition des nouveaux médias ont contraint l’industrie télévisuelle à changer, parfois contre son gré. C’est le cas de la chaîne généraliste américaine NBC, pour qui cette période de transition a été particulièrement difficile à traverser. Au cœur de ce moment charnière dans l’histoire de la télévision aux États-Unis, la sitcom Community (NBC, 2009- 2014; Yahoo!Screen, 2015) incarne et témoigne bien de différentes transformations amenées par cette convergence entre Internet et la télévision et des conséquences de cette dernière dans l’industrie télévisuelle. L’observation du parcours tumultueux de la comédie de situation ayant débuté sur les ondes de NBC dans le cadre de sa programmation Must-See TV, entre 2009 et 2014, avant de se terminer sur le service par contournement Yahoo! Screen, en 2015, permet de constater que Community est un objet télévisuel qui a constamment cherché à s’adapter à un média en pleine mutation. -

Empathy in Rudyard Kipling's Jungle Books, Mirrored in Illustrations By

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, January 2018, Vol. 8, No. 1, 1-31 doi: 10.17265/2159-5836/2018.01.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING Empathy in Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Books, Mirrored in Illustrations by John Lockwood Kipling and Aldren Watson Norman Arthur Fischer Kent State University (Retired), Kent, Ohio, USA Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Books depict empathy in the animal and animal-human world, and the illustrations of Rudyard’s father, John Lockwood Kipling, and the American artist and prolific illustrator, Aldren Watson, help depict that empathy. Lockwood Kipling was both influence on and interpreter of the Jungle Books, as shown above all in the development from his Beast and Man in India of 1891 through his illustrations for the 1894 Jungle Book, and 1895 Second Jungle Book, to his illustrations that appear in the rearranged stories of The Jungle Book, and Second Jungle Book in the 1897 Scribners Outward Bound (O/B) editions. A variation on Lockwood’s O/B mode of Jungle Books illustrations is found in Watson’s illustrations for the 1948 Doubleday edition, Jungle Books, which is the title I will use throughout.1 Part One details the influence of two animal empathy writers, Lockwood Kipling and Ernest Thompson Seton, on the Jungle Books. Part Two uses recent philosophical studies of empathy in the animal and human relationship. Part Three applies a German philosophy of art history to the new look of the O/B and Doubleday Jungle Books. Part Four interprets selected Jungle Books stories in the light of Parts one, two and three. -

Ancient Greek Tragedy and Irish Epic in Modern Irish

MEMORABLE BARBARITIES AND NATIONAL MYTHS: ANCIENT GREEK TRAGEDY AND IRISH EPIC IN MODERN IRISH THEATRE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Notre Dame in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Katherine Anne Hennessey, B.A., M.A. ____________________________ Dr. Susan Cannon Harris, Director Graduate Program in English Notre Dame, Indiana March 2008 MEMORABLE BARBARITIES AND NATIONAL MYTHS: ANCIENT GREEK TRAGEDY AND IRISH EPIC IN MODERN IRISH THEATRE Abstract by Katherine Anne Hennessey Over the course of the 20th century, Irish playwrights penned scores of adaptations of Greek tragedy and Irish epic, and this theatrical phenomenon continues to flourish in the 21st century. My dissertation examines the performance history of such adaptations at Dublin’s two flagship theatres: the Abbey, founded in 1904 by W.B. Yeats and Lady Gregory, and the Gate, established in 1928 by Micheál Mac Liammóir and Hilton Edwards. I argue that the potent rivalry between these two theatres is most acutely manifest in their production of these plays, and that in fact these adaptations of ancient literature constitute a “disputed territory” upon which each theatre stakes a claim of artistic and aesthetic preeminence. Partially because of its long-standing claim to the title of Ireland’s “National Theatre,” the Abbey has been the subject of the preponderance of scholarly criticism about the history of Irish theatre, while the Gate has received comparatively scarce academic attention. I contend, however, that the history of the Abbey--and of modern Irish theatre as a whole--cannot be properly understood except in relation to the strikingly different aesthetics practiced at the Gate. -

It Reveals Who I Really Am”: New Metaphors, Symbols, and Motifs in Representations of Autism Spectrum Disorders in Popular Culture

“IT REVEALS WHO I REALLY AM”: NEW METAPHORS, SYMBOLS, AND MOTIFS IN REPRESENTATIONS OF AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDERS IN POPULAR CULTURE By Summer Joy O’Neal A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Middle Tennessee State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Angela Hague, Chair Dr. David Lavery Dr. Robert Petersen Copyright © 2013 Summer Joy O’Neal ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There simply is not enough thanks to thank my family, my faithful parents, T. Brian and Pamela O’Neal, and my understanding sisters, Auburn and Taffeta, for their lifelong support; without their love, belief in my strengths, patience with my struggles, and encouragement, I would not be in this position today. I am forever grateful to my wonderful director, Dr. Angela Hague, whose commitment to this project went above and beyond what I deserved to expect. To the rest of my committee, Dr. David Lavery and Dr. Robert Petersen, for their seasoned advice and willingness to participate, I am also indebted. Beyond these, I would like to recognize some “unofficial” members of my committee, including Dr. Elyce Helford, Dr. Alicia Broderick, Ari Ne’eman, Chris Foss, and Melanie Yergau, who graciously offered me necessary guidance and insightful advice for this project, particularly in the field of Disability Studies. Yet most of all, Ephesians 3.20-21. iii ABSTRACT Autism has been sensationalized by the media because of the disorder’s purported prevalence: Diagnoses of this condition that was traditionally considered to be quite rare have radically increased in recent years, and an analogous fascination with autism has emerged in the field of popular culture. -

Louis Vyner Performance Competition Final Round

The Tell School of Music at Millersville University Presents Louis Vyner Performance Competition Final Round March 31, 2021 3:00pm Biemesderfer Concert Hall Joan Allen, piano Each contestant will perform for no more than twenty minutes. Selections to be chosen from: Concertino for Flute and Piano Cécile Chaminade (1857-1944) La Flûte de Pan Jules Mouquet (1867-1946) II Pan et Les Oiseaux Michael McCall, flute DUAL BA & BSE-MUED Hershey, PA “Ach, Ich Fühl’s” from Die Zauberflöte Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1765-1791) II Andante sostenuto “Una Voce Poco Fa” from Il Barbiere di Siviglia Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868) Allegra Banks, voice BA Music Lancaster, PA Ballade No. 1 in G minor, Op. 23 Frédéric Chopin (1810-1849) Transcendental Etude No 10 in F Minor Franz Liszt (1811-1886) Xingze Jiang, piano BA Music China Fantasia for Soprano Saxophone Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887-1959) I Prelude, Cadence and Filane Alfred Desenclos (1912-1971) Prelude Cadence Joshua Kim, saxophone DUAL BA & BSE-MUED Allentown, PA “O Mio Babbino Caro” from Gianni Schicchi Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924) Morgen!, Op. 27 No. 4 and Die Nacht, Op. 10 No. 3 Richard Strauss (1864-1949) Sarah Madonna, voice BSE-MUED Avondale, PA ~~~~~~ Judges Deliberate - Special Performance Jeux d'eau (Water Games) Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) Wanli Wang, Piano BA-Music China 2020 Louis Vyner Performance Award Winner ~~~~~~ 2021 Louis Vyner Performance Award Winner Announced ~~~~~~ Michael McCall is a student of Prof. Joel Behrens Sarah Madonna is a student of Dr. Jeffrey Gemmell Joshua Kim is a student of Prof. Ryan Kauffman Xingze Jiang is a student of Dr. -

The Influence of the Domestication of Death and Communal Grieving in Nineteenth-Century Cedarville (1898 – September-December)

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Research Papers Martha McMillan Journal Collection Spring 2015 The nflueI nce of the Domestication of Death and Communal Grieving in Nineteenth-Century Cedarville (1898) Kathy S. Roberts Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/ mcmillan_research_papers Part of the Agriculture Commons, Animal Sciences Commons, Christianity Commons, Civic and Community Engagement Commons, Education Commons, and the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons The McMillan Journal Collection is an archive of the journals of Martha McMillan of Cedarville, Ohio, who maintained a daily journal from 1867 until her death in 1913. Recommended Citation Roberts, Kathy S., "The nflueI nce of the Domestication of Death and Communal Grieving in Nineteenth-Century Cedarville (1898)" (2015). Research Papers. 1. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/mcmillan_research_papers/1 This Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Influence of the Domestication of Death and Communal Grieving in Nineteenth-Century Cedarville (1898 – September-December) Kathy Roberts 2015 A community’s view of death reveals its perspective on life. Though death remains constant throughout time, various communities address death differently. Researchers can study a group’s worldview by analyzing how the community addresses illness, grieves, and remembers its dead. People have always feared death, but a paradigm switch began in America after the Enlightenment. However, while the secular world transitioned its view on death, Christians remained unique in their view of death, even though their views differed by denomination. -

20Th Century Book Inside

Y Y R R U U T T N N E E R R E E C C V V O O h h t t C C S S 0 0 I I music of the D D 2 2 DISCOVER MUSIC OF THE 2Oth CENTURY 8.558168–69 20th Century Cover 6/8/05 15:22 Page 1 20th Century Booklet revised 12/9/05 3:22 pm Page 3 DISCOVER music of the 20th CENTURY Contents page Track list 4 Music of the Twentieth Century, by David McCleery 9 I. Introduction 10 II. Pointing the Way Forward 13 III. Post-Romanticism 17 IV. Serialism and Twelve-Tone Music 24 V. Neoclassicism 34 VI. An English Musical Renaissance 44 VII. Nationalist Music 55 VIII. Music from Behind the Iron Curtain 64 IX. The American Tradition 74 X. The Avant Garde 85 XI. Beyond the Avant Garde 104 XII. A Second Musical Renaissance in England 118 XIII. Into the Present 124 Sources of featured panels 128 A Timeline of the Twentieth Century (music, history, art and architecture, literature) 130 Further Listening 150 Composers of the Twentieth Century 155 Map 164 Glossary 166 Credits 179 3 20th Century Booklet revised 12/9/05 3:22 pm Page 4 DISCOVER music of the 20th CENTURY Track List CD 1 Claude Debussy (1862–1918) 1 Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune 10:33 BRT Philharmonic Orchestra, Brussels / Alexander Rahbari 8.550262 Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951) Five Piano Pieces, Op. 23 2 Walzer 3:30 Peter Hill, piano 8.553870 Alban Berg (1885–1935) Violin Concerto 3 Movement 1: Andante – Scherzo 11:29 Rebecca Hirsch, violin / Netherlands Radio Symphony Orchestra / Eri Klas 8.554755 Anton Webern (1883–1945) Five Pieces, Op. -

International Producer/Dj, Yultron & Multi-Platinum

INTERNATIONAL PRODUCER/DJ, YULTRON & MULTI-PLATINUM HIP-HOP ARTIST, JAY PARK RELEASE CROSSOVER EP, ON FIRE ON H1GHR MUSIC Featuring Lead Single, “West Coast” and Three New Tracks The Duo Unveil Music Video for Title Track, “On Fire” Download/Listen to Yultron x Jay Park On Fire EP HERE Watch “On Fire” Music Video HERE Download Album Artwork and Press Images HERE (Credit: H1GHR Music) AUGUST 30, 2019 (LOS ANGELES, CA) – International producer and DJ, Yultron, and multi- platinum hip-hop artist, Jay Park, today released their crossover EP On Fire, along with the music video for their track of the same name “On Fire,” on Park’s label, H1GHR Music. The collaboration mashes up the artists' worlds of dance and hip-hop, east and west, and ranges sonically from smooth pop, energetic dance drops, to hard hip-hop. The EP also includes appearances from emerging Korean artists Sik-K, PH-1, and Haon. “Jay and I have been friends for some time and we really vibe working together,” said Yultron. “All genres inspire me, so I was excited to work on this crossover EP that melds our worlds together. We were both creatively ‘on fire’ throughout the whole process.” “I like to explore new genres and Yultron is a good friend and very chill,” said Jay Park. “We set out to collab using influences of hip-hop, EDM, pop and K-pop. I love the range of the tracks we put out on this EP and its vibe.” Yultron and Jay Park’s kinship spans several years, starting with their first song "BO$$," which hit #1 on Korea's charts in 2015. -

History of Hot Springs National Park

... ~! I~;~~~~,~--,:;:~,-:~-~~·· D -13 k. !'.::-"'!, .,,j •',·'; I ; .• ' ' I ; ' \ ., ") .• >; • •'.. : .: . ., .. i!}: . ,cirHrSTORr C8 .BOT SPrttNOS NATIOOAL P~.RI . _........_. ---. ", ~· •'i · .•/.i::· ;~ ,. r·'> )• .. ' ,"t_ 7 ·1.orr~s:t·M. Beneosr'.and tcnald ·s. Libbey ··:>'.··~-. '.,,t··~' r ... ,\;; , ' -< '·.,, ..: :~:·,;r-;.. · <"'.< .;~~:f~1f::p 1ABL! ~:~TmTs './" 1• " ""-'.1, ~ \·~ > '- ,' :. /' ~ ~ , \' ; ; ' -- '-!. • ' Introduction .... •:••.• •• , •• ••.•·••••••••••••••••••••••••••• • • •.• • • l Aboriginal Ri•toZ'J'•,• •••••,~ ..... ~ •. •·• •.• • •••• • •••••• ~ •••••••••• •. • 3 . ' Coming ot The White Man •••••· ••••••• , •••. , •••••••••••••••••••••• 6 Louiaiana Territory Under Other Flags ••••••• ~................. 8 ~· . l ·.· Hote~, • .~a thhou.sea •••••••••••• •.. • ~ --~- .......................... lh ~ans-port4tion ••••••••• •.• •••••• • • .-~ • • •• •• •••••••••• • •••••••••• 21 // . ••• f!?indary ·St.a tus •••.••••••••••••• • • • • •. • •••• '! , ................. • • • .FedeNt1. 18st~trat1on Bonrd,._ ••• ••J •;• •••••• • ••••••••••• • ••• • •• •• 27 Legietitive History•• ~~ ••••••• •••.••••••••••••••*••••••••••••••• 32 I . -.... Appo~tive Off1ciais ~ Charge ••• •••.~ •••• " ............ •.•• •• •" liO Mincttllaneoua Important Dntes ••••· • ., •• ••••••• : •••••••••••• -~-•••• . ·"tfP Dibl1ogl"aphy•• • •••••••••• •:• •.• t'9 ....... • •-•. •. • •. • •• • ••• •. • ..... • • • • ~.-<-:-; . B& W Scans ~.. s~s·.zo0s- ON MICRORLM ATTENTION: Portions of this Scanned docu1nent are illegible due to the poor quality -

DISTINGUISHED Residentsof

DISTINGUISHED 1 RESI D ENTS of Hillside Memorial Park and Mortuary DISTINGUISHED RESIDENTS IRV I NG AA RONSON (1895 – 1963) EV E RL A ST I NG Pea C E Irving Aaronson’s career began at the age of 11 as a movie theater pianist. DISTINGUISHED RE S I D E NTS GU I D E : A LE G A CY OF LE G E NDS In the 1920’s he became a Big Band leader with the Versatile Sextette and Irving Aaronson & the Commanders. The Commanders recorded “I’ll Get By,” Cole Porter’s “Let’s Misbehave,” “All By Ourselves in the Hillside Memorial Park and Mortuary has provided a place to Moonlight,” “Don’t Look at Me That Way” and “Hi-Ho the Merrio.” Irving Aaronson His band included members Gene Krupa, Claude Thornhill and Artie honor the accomplishments and legacies of the Jewish community Shaw. He later worked for MGM as a music coordinator for “Arrivederci Roma” (1957), “This Could Be the Night” (1957), “Meet Me in Las Vegas” since 1942. We have made it our mission to provide southern (1956) and as music advisor for “The Merry Widow” (1952). California with a memorial park and mortuary dedicated to ROSLYN ALF I N –SL A T E R (1916 – 2002) GA RD E N OF SA R A H honoring loved ones in a manner that is fitting and appropriate. Dr. Roslyn Alfin-Slater was a highly esteemed UCLA professor and nutrition expert. Her early work included studies on the relationship between cholesterol and essential fatty acid metabolism. -

G R O S S E P O I N T E N E W S ♦ Ju N E 7 ,2 0 1 2

SUBSCRIBE NOW (313) 343-5578 Standard $14.50 OFF THE NEWSSTAND PRICE G rosse Pointe N ew s VOL. 73, NO. 23,38 PAGES TTINF7 2012 ONE DOLLAR (DELIVERY 7 One of America’s great community newspapers since 1940 GROSSE POINTE, MICHIGAN SAVE with the Grosse Pointe News! Graduation day Outages Liggett Scholar and Valedictorian Patrick Thomas addresses the crowd at University Liggett School’s Class of 2012 graduation cer irk emonies, held Sunday, June 3, at the Cook Road campus. resident By Brad lindberg Staffwriter GROSSE POINTE FARMS — Mike Thomas is tired of power week ahead outages. “It seems that every time it 3 4. 5 ft 7 8 9 gets 90 degrees or more, the PHOTOS BY RENEE LANDUYT power goes out,” said 10 11 12 13 14 -st; ■?£> Thomas, a homeowner on McMillan between Ridge and Charlevoix for nearly 20 THURSDAY, JUNE 7 years. ♦ Grosse Pointe North “It has come to light in the and South High School last two years that we have an jazz bands open the 25th infrastructure problem,” he annual Music on The said. Plaza free outdoor con In addition to flooding last cert series at 7 p.m. on summer, he said he’s had two The Village Festival Plaza, power failures this year. at the comer of Kercheval Outages are so common, and St. Clair, City of Thomas said he knows when Grosse Pointe. Attendees they’re coming. should bring a chair. “Just before it happens, I can look out my back window SATURDAY, JUNE 9 toward my neighbor’s house ♦ Dermatologist Shauna and hear the popping and see Ryder-Diggs, M.D.