Molecular Phylogenesis of Mediterranean Octocorals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[Oceanography and Marine Biology - an Annual Review] R. N](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2073/oceanography-and-marine-biology-an-annual-review-r-n-12073.webp)

[Oceanography and Marine Biology - an Annual Review] R. N

OCEANOGRAPHY and MARINE BIOLOGY AN ANNUAL REVIEW Volume 44 7044_C000.fm Page ii Tuesday, April 25, 2006 1:51 PM OCEANOGRAPHY and MARINE BIOLOGY AN ANNUAL REVIEW Volume 44 Editors R.N. Gibson Scottish Association for Marine Science The Dunstaffnage Marine Laboratory Oban, Argyll, Scotland [email protected] R.J.A. Atkinson University Marine Biology Station Millport University of London Isle of Cumbrae, Scotland [email protected] J.D.M. Gordon Scottish Association for Marine Science The Dunstaffnage Marine Laboratory Oban, Argyll, Scotland [email protected] Founded by Harold Barnes Boca Raton London New York CRC is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group 6000 Broken Sound Parkway NW, Suite 300 Boca Raton, FL 33487-2742 © 2006 by R.N. Gibson, R.J.A. Atkinson and J.D.M. Gordon CRC Press is an imprint of Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa business No claim to original U.S. Government works Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 International Standard Book Number-10: 0-8493-7044-2 (Hardcover) International Standard Book Number-13: 978-0-8493-7044-1 (Hardcover) International Standard Serial Number: 0078-3218 This book contains information obtained from authentic and highly regarded sources. Reprinted material is quoted with permission, and sources are indicated. A wide variety of references are listed. Reasonable efforts have been made to publish reliable data and information, but the author and the publisher cannot assume responsibility for the valid- ity of all materials or for the consequences of their use. -

Octocoral Diversity of Balıkçı Island, the Marmara Sea

J. Black Sea/Mediterranean Environment Vol. 19, No. 1: 46-57 (2013) RESEARCH ARTICLE Octocoral diversity of Balıkçı Island, the Marmara Sea Eda Nur Topçu1,2*, Bayram Öztürk1,2 1Faculty of Fisheries, Istanbul University, Ordu St., No. 200, 34470, Laleli, Istanbul, TURKEY 2Turkish Marine Research Foundation (TUDAV), P.O. Box: 10, Beykoz, Istanbul, TURKEY *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract We investigated the octocoral diversity of Balıkçı Island in the Marmara Sea. Three sites were sampled by diving, from 20 to 45 m deep. Nine species were found, two of which are first records for Turkish fauna: Alcyonium coralloides and Paralcyonium spinulosum. Scientific identification of Alcyonium acaule in the Turkish seas was also done for the first time in this study. Key words: Octocoral, soft coral, gorgonian, diversity, Marmara Sea. Introduction The Marmara Sea is a semi-enclosed sea connecting the Black Sea to the Aegean Sea via the Turkish Straits System, with peculiar oceanographic, ecological and geomorphologic characteristics (Öztürk and Öztürk 1996). The benthic fauna consists of Black Sea species until approximately 20 meters around the Prince Islands area, where Mediterranean species take over due to the two layer stratification in the Marmara Sea. The Sea of Marmara, together with the straits of Istanbul and Çanakkale, serves as an ecological barrier, a biological corridor and an acclimatization zone for the biota of Mediterranean and Black Seas (Öztürk and Öztürk 1996). The Islands in the Sea of Marmara constitute habitats particularly for hard bottom communities of Mediterranean origin. Ten Octocoral species were reported by Demir (1954) from the Marmara Sea but amongst them, Gorgonia flabellum was probably reported by mistake and 46 should not be considered as a valid record from the Sea of Marmara. -

Active and Passive Suspension Feeders in a Coralligenous Community

! Chapter_0_Martina 05/06/15 07:23 Página 1 The importance of benthic suspension feeders in the biogeochemical cycles: active and passive suspension feeders in a coralligenous community PhD THESIS Martina Coppari Barcelona, 2015 Chapter_0_Martina 05/06/15 07:23 Página 2 Photos by: Federico Betti, Georgios Tsounis Design: Antonio Secilla Chapter_0_Martina 05/06/15 07:23 Página 3 The importance of benthic suspension feeders in the biogeochemical cycles: active and passive suspension feeders in a coralligenous community PhD THESIS MARTINA COPPARI Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Institut de Ciència i Tecnologia Ambientals PhD Programme in Environmental Science and Technology June 2015 Director de la Tesi Director de la Tesi Dr. Sergio Rossi Dr. Andrea Gori Investigador Investigador Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona Universitat de Barcelona Institut de Ciència i Tecnologia Ambientals Departament d’Ecologia • 3 • Chapter_0_Martina 05/06/15 07:23 Página 4 . Chapter_0_Martina 05/06/15 07:23 Página 5 Para los que me han acompañado en este viaje • 5 • Chapter_0_Martina 05/06/15 07:23 Página 6 . Chapter_0_Martina 05/06/15 07:23 Página 7 Resumen 11 Abstract 13 Introduction 15 Chapter 1 Size, spatial and bathymetrical distribution of the ascidian Halocynthia papillosa in Mediterranean coastal bottoms: benthic-pelagic implications 29 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................30 2. Materials -

Di Camillo Et Al 2017

This is a post-peer-review, pre-copyedit version of an article published in Biodiversity and Conservation on 23 December 2017 (First Online). The final authenticated version is available online at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-017-1492-8 https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs10531-017-1492-8 An embargo period of 12 months applies to this Journal. This paper has received funding from the European Union (EU)’s H2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 643712 to the project Green Bubbles RISE for sustainable diving (Green Bubbles). This paper reflects only the authors’ view. The Research Executive Agency is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains. © 2017. This manuscript version is made available under the CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 AUTHORS' ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT Building a baseline for habitat-forming corals by a multi-source approach, including Web Ecological Knowledge - Cristina G Di Camillo, Department of Life and Environmental Sciences, Marche Polytechnic University, CoNISMa, Ancona, Italy, [email protected] - Massimo Ponti, Department of Biological, Geological and Environmental Sciences and Interdepartmental Research Centre for Environmental SciencesUniversity of Bologna, CoNISMa, Ravenna, Italy - Giorgio Bavestrello, Department of Earth, Environment and Life Sciences, University of Genoa, CoNISMa, Genoa, Italy - Maja Krzelj, Department of Marine Studies, University of Split, Split, Croatia - Carlo Cerrano, Department of Life and Environmental Sciences, Marche Polytechnic University, CoNISMa, Ancona, Italy Received: 12 January 2017 Revised: 10 December 2017 Accepted: 14 December 2017 First online: 23 December 2017 Cite as: Di Camillo, C.G., Ponti, M., Bavestrello, G. -

SOUTH AFRICAN ASSOCIATION for MARINE BIOLOGICAL RESEARCH OCEANOGRAPHIC RESEARCH INSTITUTE Investigational Report No. 68 Corals O

SOUTH AFRICAN ASSOCIATION FOR MARINE BIOLOGICAL RESEARCH OCEANOGRAPHIC RESEARCH INSTITUTE Investigational Report No. 68 Corals of the South-west Indian Ocean II. Eleutherobia aurea spec. nov. (Cnidaria, Alcyonacea) from deep reefs on the KwaZulu-Natal Coast, South Africa by Y. Benayahu and M.H. Sch layer Edited by M.H. Schleyer Published by THE OCEANOGRAPHIC RESEARCH INSTITUTE P.0 Box 10712, Manne Parade 4056 DURBAN SOUTH AFRICA October 1995 Copynori ISBN 0 66989 07« 3 ISSN 0078-320X Frontispiece. Colony of Eleutherobia aurea spec. nov. in Its natural habitat with its polyps expanded Eleutherobia aurea spec. nov. (Cnidaria, Alcyonacea) from deep reefs on the KwaZulu-Natal coast, South Africa by Y. Benayahui and M. H. Schleyeri 'Department of Zoology, George S. Wise Faculty of Life Sciences. Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv, Tel Aviv 69978, Israel. ^Oceanographic Research Institute, P.O. Box 10712, Marine Parade 4056, Durban, South Africa. ABSTRACT Eleutherobia aurea spec. nov. is a new octocoral species (family Alcyoniidae) described from material collected on deep reefs along the coast of KwaZulu- Natal, South Africa. The species has spheroid, radiate and double deltoid sclerites, the latter being the most conspicuous sclerites and aiso the most abundant in the interior of the colony. Keywords: Eleutherobia, Cnidaria, Alcyonacea. Octocorallia, coral reefs, South Africa. INTRODUCTION The alcyonacean fauna of southern Africa (Cnidaria, Octocorallia) has been thoroughly examined and revised by Williams (1992). The tropical coastal area of northern KwaZulu-Natal has recently been investigated at Sodwana Bay and yielded 37 species of the families Tubiporidae. Alcyoniidae and Xeniidae (Benayahu, 1993). Further collections conducted on the deeper reef areas of Two-Mile Reef at Sodwana Bay. -

Coelenterata: Anthozoa), with Diagnoses of New Taxa

PROC. BIOL. SOC. WASH. 94(3), 1981, pp. 902-947 KEY TO THE GENERA OF OCTOCORALLIA EXCLUSIVE OF PENNATULACEA (COELENTERATA: ANTHOZOA), WITH DIAGNOSES OF NEW TAXA Frederick M. Bayer Abstract.—A serial key to the genera of Octocorallia exclusive of the Pennatulacea is presented. New taxa introduced are Olindagorgia, new genus for Pseudopterogorgia marcgravii Bayer; Nicaule, new genus for N. crucifera, new species; and Lytreia, new genus for Thesea plana Deich- mann. Ideogorgia is proposed as a replacement ñame for Dendrogorgia Simpson, 1910, not Duchassaing, 1870, and Helicogorgia for Hicksonella Simpson, December 1910, not Nutting, May 1910. A revised classification is provided. Introduction The key presented here was an essential outgrowth of work on a general revisión of the octocoral fauna of the western part of the Atlantic Ocean. The far-reaching zoogeographical affinities of this fauna made it impossible in the course of this study to ignore genera from any part of the world, and it soon became clear that many of them require redefinition according to modern taxonomic standards. Therefore, the type-species of as many genera as possible have been examined, often on the basis of original type material, and a fully illustrated generic revisión is in course of preparation as an essential first stage in the redescription of western Atlantic species. The key prepared to accompany this generic review has now reached a stage that would benefit from a broader and more objective testing under practical conditions than is possible in one laboratory. For this reason, and in order to make the results of this long-term study available, even in provisional form, not only to specialists but also to the growing number of ecologists, biochemists, and physiologists interested in octocorals, the key is now pre- sented in condensed form with minimal illustration. -

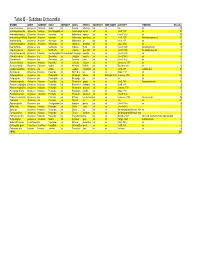

Table B – Subclass Octocorallia

Table B – Subclass Octocorallia BINOMEN ORDER SUBORDER FAMILY SUBFAMILY GENUS SPECIES SUBSPECIES COMN_NAMES AUTHORITY SYNONYMS #Records Acanella arbuscula Alcyonacea Calcaxonia Isididae n/a Acanella arbuscula n/a n/a n/a n/a 59 Acanthogorgia armata Alcyonacea Holaxonia Acanthogorgiidae n/a Acanthogorgia armata n/a n/a Verrill, 1878 n/a 95 Anthomastus agassizii Alcyonacea Alcyoniina Alcyoniidae n/a Anthomastus agassizii n/a n/a (Verrill, 1922) n/a 35 Anthomastus grandiflorus Alcyonacea Alcyoniina Alcyoniidae n/a Anthomastus grandiflorus n/a n/a Verrill, 1878 Anthomastus purpureus 37 Anthomastus sp. Alcyonacea Alcyoniina Alcyoniidae n/a Anthomastus sp. n/a n/a Verrill, 1878 n/a 1 Anthothela grandiflora Alcyonacea Scleraxonia Anthothelidae n/a Anthothela grandiflora n/a n/a (Sars, 1856) n/a 24 Capnella florida Alcyonacea n/a Nephtheidae n/a Capnella florida n/a n/a (Verrill, 1869) Eunephthya florida 44 Capnella glomerata Alcyonacea n/a Nephtheidae n/a Capnella glomerata n/a n/a (Verrill, 1869) Eunephthya glomerata 4 Chrysogorgia agassizii Alcyonacea Holaxonia Acanthogorgiidae Chrysogorgiidae Chrysogorgia agassizii n/a n/a (Verrill, 1883) n/a 2 Clavularia modesta Alcyonacea n/a Clavulariidae n/a Clavularia modesta n/a n/a (Verrill, 1987) n/a 6 Clavularia rudis Alcyonacea n/a Clavulariidae n/a Clavularia rudis n/a n/a (Verrill, 1922) n/a 1 Gersemia fruticosa Alcyonacea Alcyoniina Alcyoniidae n/a Gersemia fruticosa n/a n/a Marenzeller, 1877 n/a 3 Keratoisis flexibilis Alcyonacea Calcaxonia Isididae n/a Keratoisis flexibilis n/a n/a Pourtales, 1868 n/a 1 Lepidisis caryophyllia Alcyonacea n/a Isididae n/a Lepidisis caryophyllia n/a n/a Verrill, 1883 Lepidisis vitrea 13 Muriceides sp. -

United Nations Unep/Med Wg.474/3 United

UNITED NATIONS UNEP/MED WG.474/3 UNITED NATIONS ENVIRONMENT PROGRAMME MEDITERRANEAN ACTION PLAN 24 Avril 2019 Original: English Meeting of the Ecosystem Approach of Correspondence Group on Monitoring (CORMON), Biodiversity and Fisheries. Rome, Italy, 12-13 May 2019 Agenda item 3: Guidance on monitoring marine benthic habitats (Common Indicators 1 and 2) Monitoring protocols of the Ecosystem Approach Common Indicators 1 and 2 related to marine benthic habitats For environmental and economy reasons, this document is printed in a limited number and will not be distributed at the meeting. Delegates are kindly requested to bring their copies to meetings and not to request additional copies. UNEP/MAP SPA/RAC - Tunis, 2019 Note by the Secretariat The 19th Meeting of the Contracting Parties to the Barcelona Convention (COP 19) agreed on the Integrated Monitoring and Assessment Programme (IMAP) of the Mediterranean Sea and Coast and Related Assessment Criteria which set, in its Decision IG.22/7, a specific list of 27 common indicators (CIs) and Good Environmental Status (GES) targets and principles of an integrated Mediterranean Monitoring and Assessment Programme. During the initial phase of the IMAP implementation (2016-2019), the Contracting parties to the Barcelona Convention updated the existing national monitoring and assessment programmes following the Decision requirements in order to provide all the data needed to assess whether ‘‘Good Environmental Status’’ defined through the Ecosystem Approach process has been achieved or maintained. In line with IMAP, Guidance Factsheets were developed, reviewed and agreed by the Meeting of the Ecosystem Approach Correspondence Group on Monitoring (CORMON) Biodiversity and Fisheries (Madrid, Spain, 28 February-1 March 2017) and the Meeting of the SPA/RAC Focal Points (Alexandria, Egypt, 9-12 May 2017) for the Common Indicators to ensure coherent monitoring. -

Marlin Marine Information Network Information on the Species and Habitats Around the Coasts and Sea of the British Isles

MarLIN Marine Information Network Information on the species and habitats around the coasts and sea of the British Isles Pink sea fan (Eunicella verrucosa) MarLIN – Marine Life Information Network Marine Evidence–based Sensitivity Assessment (MarESA) Review John Readman & Dr Keith Hiscock 2017-03-30 A report from: The Marine Life Information Network, Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. Please note. This MarESA report is a dated version of the online review. Please refer to the website for the most up-to-date version [https://www.marlin.ac.uk/species/detail/1121]. All terms and the MarESA methodology are outlined on the website (https://www.marlin.ac.uk) This review can be cited as: Readman, J.A.J. & Hiscock, K. 2017. Eunicella verrucosa Pink sea fan. In Tyler-Walters H. and Hiscock K. (eds) Marine Life Information Network: Biology and Sensitivity Key Information Reviews, [on-line]. Plymouth: Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. DOI https://dx.doi.org/10.17031/marlinsp.1121.1 The information (TEXT ONLY) provided by the Marine Life Information Network (MarLIN) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-Share Alike 2.0 UK: England & Wales License. Note that images and other media featured on this page are each governed by their own terms and conditions and they may or may not be available for reuse. Permissions beyond the scope of this license are available here. Based on a work at www.marlin.ac.uk (page left blank) Date: 2017-03-30 Pink sea fan (Eunicella verrucosa) - Marine Life Information Network See online review for distribution map Two fans of Eunicella verrucosa showing the two morphs, pink and white. -

DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS of the 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project

DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS OF THE 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project March 2018 DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS OF THE 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project Citation: Aguilar, R., García, S., Perry, A.L., Alvarez, H., Blanco, J., Bitar, G. 2018. 2016 Deep-sea Lebanon Expedition: Exploring Submarine Canyons. Oceana, Madrid. 94 p. DOI: 10.31230/osf.io/34cb9 Based on an official request from Lebanon’s Ministry of Environment back in 2013, Oceana has planned and carried out an expedition to survey Lebanese deep-sea canyons and escarpments. Cover: Cerianthus membranaceus © OCEANA All photos are © OCEANA Index 06 Introduction 11 Methods 16 Results 44 Areas 12 Rov surveys 16 Habitat types 44 Tarablus/Batroun 14 Infaunal surveys 16 Coralligenous habitat 44 Jounieh 14 Oceanographic and rhodolith/maërl 45 St. George beds measurements 46 Beirut 19 Sandy bottoms 15 Data analyses 46 Sayniq 15 Collaborations 20 Sandy-muddy bottoms 20 Rocky bottoms 22 Canyon heads 22 Bathyal muds 24 Species 27 Fishes 29 Crustaceans 30 Echinoderms 31 Cnidarians 36 Sponges 38 Molluscs 40 Bryozoans 40 Brachiopods 42 Tunicates 42 Annelids 42 Foraminifera 42 Algae | Deep sea Lebanon OCEANA 47 Human 50 Discussion and 68 Annex 1 85 Annex 2 impacts conclusions 68 Table A1. List of 85 Methodology for 47 Marine litter 51 Main expedition species identified assesing relative 49 Fisheries findings 84 Table A2. List conservation interest of 49 Other observations 52 Key community of threatened types and their species identified survey areas ecological importanc 84 Figure A1. -

Marine Invertebrate Diversity in Aristotle's Zoology

Contributions to Zoology, 76 (2) 103-120 (2007) Marine invertebrate diversity in Aristotle’s zoology Eleni Voultsiadou1, Dimitris Vafi dis2 1 Department of Zoology, School of Biology, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, GR - 54124 Thessaloniki, Greece, [email protected]; 2 Department of Ichthyology and Aquatic Environment, School of Agricultural Sciences, Uni- versity of Thessaly, 38446 Nea Ionia, Magnesia, Greece, dvafi [email protected] Key words: Animals in antiquity, Greece, Aegean Sea Abstract Introduction The aim of this paper is to bring to light Aristotle’s knowledge Aristotle was the one who created the idea of a general of marine invertebrate diversity as this has been recorded in his scientifi c investigation of living things. Moreover he works 25 centuries ago, and set it against current knowledge. The created the science of biology and the philosophy of analysis of information derived from a thorough study of his biology, while his animal studies profoundly infl uenced zoological writings revealed 866 records related to animals cur- rently classifi ed as marine invertebrates. These records corre- the origins of modern biology (Lennox, 2001a). His sponded to 94 different animal names or descriptive phrases which biological writings, constituting over 25% of the surviv- were assigned to 85 current marine invertebrate taxa, mostly ing Aristotelian corpus, have happily been the subject (58%) at the species level. A detailed, annotated catalogue of all of an increasing amount of attention lately, since both marine anhaima (a = without, haima = blood) appearing in Ar- philosophers and biologists believe that they might help istotle’s zoological works was constructed and several older in the understanding of other important issues of his confusions were clarifi ed. -

![Genetic Divergence and Polyphyly in the Octocoral Genus Swiftia [Cnidaria: Octocorallia], Including a Species Impacted by the DWH Oil Spill](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9917/genetic-divergence-and-polyphyly-in-the-octocoral-genus-swiftia-cnidaria-octocorallia-including-a-species-impacted-by-the-dwh-oil-spill-739917.webp)

Genetic Divergence and Polyphyly in the Octocoral Genus Swiftia [Cnidaria: Octocorallia], Including a Species Impacted by the DWH Oil Spill

diversity Article Genetic Divergence and Polyphyly in the Octocoral Genus Swiftia [Cnidaria: Octocorallia], Including a Species Impacted by the DWH Oil Spill Janessy Frometa 1,2,* , Peter J. Etnoyer 2, Andrea M. Quattrini 3, Santiago Herrera 4 and Thomas W. Greig 2 1 CSS Dynamac, Inc., 10301 Democracy Lane, Suite 300, Fairfax, VA 22030, USA 2 Hollings Marine Laboratory, NOAA National Centers for Coastal Ocean Sciences, National Ocean Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 331 Fort Johnson Rd, Charleston, SC 29412, USA; [email protected] (P.J.E.); [email protected] (T.W.G.) 3 Department of Invertebrate Zoology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, 10th and Constitution Ave NW, Washington, DC 20560, USA; [email protected] 4 Department of Biological Sciences, Lehigh University, 111 Research Dr, Bethlehem, PA 18015, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Mesophotic coral ecosystems (MCEs) are recognized around the world as diverse and ecologically important habitats. In the northern Gulf of Mexico (GoMx), MCEs are rocky reefs with abundant black corals and octocorals, including the species Swiftia exserta. Surveys following the Deepwater Horizon (DWH) oil spill in 2010 revealed significant injury to these and other species, the restoration of which requires an in-depth understanding of the biology, ecology, and genetic diversity of each species. To support a larger population connectivity study of impacted octocorals in the Citation: Frometa, J.; Etnoyer, P.J.; GoMx, this study combined sequences of mtMutS and nuclear 28S rDNA to confirm the identity Quattrini, A.M.; Herrera, S.; Greig, Swiftia T.W.