Centre for Economic Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zn the Nineteenth Century

INTERNATIONAL LIBRARY OF SOCIOLOGY British AND SOCIAL RECONSTRUCTION Founded by Karl Mannhelm Social Work Editor W. J. H. Sprott zn the Nineteenth Century by A. F. Young and E. T. Ashton BC B 20623 73 9177 A catalogue of books available In the IN'rERNATIONAL LlDRARY OF ROUTLEDGE & KEGAN PAUL LTD SOCIOLOGY AND SOCIAL RECONSTRUCTION and new books m Broadway House, 68-74 Carter Lane preparation for the Library will be found at the end of this volume London, E.C.4 UIA-BIBLIOTHEEK 111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 11 """ ------------------------ Text continues after this page ------------------------ This publication is made available in the context of the history of social work project. See www.historyofsocialwork.org It is our aim to respect authors’ and publishers’ copyright. Should you feel we violated those, please do get in touch with us. Deze publicatie wordt beschikbaar gesteld in het kader van de canon sociaal werk. Zie www.canonsociaalwerk.eu Het is onze wens de rechten van auteurs en uitgevers te respecten. Mocht je denken dat we daarin iets fout doen, gelieve ons dan te contacteren. ------------------------ Tekst gaat verder na deze pagina ------------------------ r-= ! First published in 1956 I by Routledge and Kegan Paul Lld Broadway House, 68-74 Carter Lane London, E.C.4 Second impresszon 1963 I Third impression 1967 Printed in Great Britatn by CONTENTS Butler and Tanner Ltd Acknowledgments vu Frome and London I Introduction page I I . PART ONE I ' IDEAS WHICH INFLUENCED THE DEVELOPMENT OF SOCIAL WORK L I Influence of social and economic thought 7 I ConditWns-2 EcoROImc and Political Theories 2 Religious thought in the nineteenth century 28 I The Church if Engtar.d-2 The Tractarians-g Tilt Chris- tian Socialists-4 The JYonconformists-5 The Methodists- 6 The Unitarians-7 The Q.uakers-8 Conclusion 3 Influence of poor law prinClples and practice 43 I TIre problems and principles of poor law administration- 2 Criticisms by Social Workers and thezr results PART TWO MAIN BRANCHES OF SOCIAL WORK 4 Family case work-I. -

The New Poor Law and the Struggle for Union Chargeability

MA URICE CA PLAN THE NEW POOR LAW AND THE STRUGGLE FOR UNION CHARGEABILITY Thrasymachus: "Listen then. I define justice or right as what is in the interest of the stronger party." Plato, The Republic, I, St. 338 While much has been heard in recent times of the evils attaching to "the principles of 1834", other important aspects of the New Poor Law have been seriously neglected. The laws of settlement and removal were unjust and inhumane, and the system of parochial rating was anomalous, uneven and, indeed, thoroughly iniquitous. One of the main features of the Poor Law Amendment Act had been the grouping of the parishes of England and Wales into unions of parishes. Those of a medium-sized town usually constituted one union, while in the countryside the typical union tended to comprise all the parishes within a radius of up to about ten miles of a country town, its centre. Under the Act, the administration of the Poor Law was based on the union and not, as heretofore, on the parish; yet the latter remained the financial unit, each parish being chargeable for its own Poor Law expenditure. This uneven arrangement prevented the effective oper- ation of the Act, and, as will be shown, had unhappy consequences. Attempts at reform in these matters were strenuously opposed in Parlia- ment between 1845 and 1865, and only in the latter year was the Union Chargeability Act passed. The purpose of the present article is to show that the main opposition to reform came from a section of the landed interest whose object was to maintain the status quo with regard to settlement law and to keep alive the pernicious distinction between open and close parishes. -

Managing Poverty in Victorian England and Wales

How Cruel was the Victorian Workhouse/Poor Law Union? ‘Living the Poorlife’ Paul Carter November 2009 MH 12/10320, Clutton Poor Law Union correspondence, 1834 – 1838. Coloured, hand drawn map of the parishes within the Clutton Poor Law Union, Somerset. 1836. Llanfyllin Workhouse Poor Law Report of the Commissioners, 1834. 1. Outdoor relief to continue for the aged and infirm – but abolished for the able bodied – who would be „offered the house‟. 2. Conditions in the workhouse to be „less eligible‟ than that of the lowest paid labourer. * To make the workhouse a feared institution of last resort. 3. Establish a central Poor Law Commission with three commissioners to oversee the poor law and create/impose national uniformity. 4. Parishes to be joined together in Poor Law Unions, share a central workhouse, governed by elected guardians, run by a master/mistress of the house. Poor Law Commission Somerset House George Nicholls, Frankland Lewis and John George Shaw-Lefevre Edwin Chadwick Assistant Poor Law Commissioners (secretary) Central workhouse 300: Poor Law Union (Board 1834-1839 of Guardians) Master/Mistress Parish A. Parish B. Parish C. Parish D. Clerk to the Guardians MH 12: Poor Law Union Correspondence 16,741 volumes. 10,881,650 folios. 21,763,300 pages. c. 200 words per page. 4,352,660,000 words. Berwick upon Tweed Tynemouth Reeth Liverpool Keighley Mansfield Basford (North Staffs) Wolstanton and Buslem, and Newcastle under Lyme Llanfyllin (North Worcs) Cardiff Kidderminster and Bromsgrove Mitford and Launditch Blything Newport Pagnell Bishops Stortford Rye Truro Axminster Clutton Southampton MH 12/5967 Liverpool Select Vestry. -

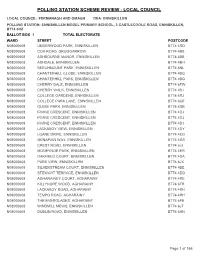

Polling Station Scheme Review - Local Council

POLLING STATION SCHEME REVIEW - LOCAL COUNCIL LOCAL COUNCIL: FERMANAGH AND OMAGH DEA: ENNISKILLEN POLLING STATION: ENNISKILLEN MODEL PRIMARY SCHOOL, 3 CASTLECOOLE ROAD, ENNISKILLEN, BT74 6HZ BALLOT BOX 1 TOTAL ELECTORATE WARD STREET POSTCODE N08000608UNDERWOOD PARK, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4RD N08000608COA ROAD, DRUMGARROW BT74 4BS N08000608ASHBOURNE MANOR, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4BB N08000608ASHDALE, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4BH N08000608BEECHMOUNT PARK, ENNISKILLEN BT74 6NL N08000608CHANTERHILL CLOSE, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4BG N08000608CHANTERHILL PARK, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4BG N08000608CHERRY DALE, ENNISKILLEN BT74 6FW N08000608CHERRY WALK, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4BJ N08000608COLLEGE GARDENS, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4RJ N08000608COLLEGE PARK LANE, ENNISKILLEN BT74 6GF N08000608GLEBE PARK, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4DB N08000608IRVINE CRESCENT, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4DJ N08000608IRVINE CRESCENT, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4DJ N08000608IRVINE CRESCENT, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4DJ N08000608LACKABOY VIEW, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4DY N08000608LOANE DRIVE, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4EG N08000608MENAPIAN WAY, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4GS N08000608CREST ROAD, ENNISKILLEN BT74 6JJ N08000608MONEYNOE PARK, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4ER N08000608OAKFIELD COURT, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4DA N08000608PARK VIEW, ENNISKILLEN BT74 6JX N08000608SILVERSTREAM COURT, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4BE N08000608STEWART TERRACE, ENNISKILLEN BT74 4EG N08000608AGHARAINEY COURT, AGHARAINY BT74 4RE N08000608KILLYNURE WOOD, AGHARAINY BT74 6FR N08000608LACKABOY ROAD, AGHARAINY BT74 4RH N08000608TEMPO ROAD, AGHARAINY BT74 4RH N08000608THE EVERGLADES, AGHARAINY BT74 6FE N08000608WINDMILL -

1926 Census County Fermanagh Report

GOVERNMENT OF NORTHERN IRELAND CENSUS OF NORTHERN IRELAND 1926 COUNTY OF FERMANAGH. Printed and presented pursuant to the provisions of 15 and 16 Geo. V., ch. 21 BELFAST: PUBLISHED BY H.M. STATIONERY OFFICE ON BEHALF OF THE GOVERNMENT OF NORTHERN IRELAND. To be purchased directly from H. M. Stationery Office at the following addresses: 15 DONEGALL SQUARE WEST, BELFAST: 120 GEORGE ST., EDINBURGH ; YORK ST., MANCHESTER ; 1 ST. ANDREW'S CRESCENT, CARDIFF ; AD ASTRAL HOUSE, KINGSWAY, LONDON, W.C.2; OR THROUGH ANY BOOKSELLER. 1928 Price 5s. Od. net THE. QUEEN'S UNIVERSITY OF BELFAST. iii. PREFACE. This volume has been prepared in accordance with the prov1s1ons of Section 6 (1) of the Census Act (Northern Ireland), 1925. The 1926 Census statistics which it contains were compiled from the returns made as at midnight of the 18-19th April, 1926 : they supersede those in the Preliminary Report published in August, 1926, and may be regarded as final. The Census· publications will consist of:-· 1. SEVEN CouNTY VoLUMES, each similar in design and scope to the present publication. 2. A GENERAL REPORT relating to Northern Ireland as a whole, covering in more detail the. statistics shown in the County Volumes, and containing in addition tables showing (i.) the occupational distribution of persons engaged in each of 51 groups of industries; (ii.) the distribution of the foreign born population by nationality, age, marital condition, and occupation; (iii.) the distribution of families of dependent children under 16 · years of age, by age, sex, marital condition, and occupation of parent; (iv.) the occupational distribution of persons suffering frominfirmities. -

The Poor Law of Lunacy

The Poor Law of Lunacy: The Administration of Pauper Lunatics in Mid-Nineteenth Century England with special Emphasis on Leicestershire and Rutland Peter Bartlett Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University College London. University of London 1993 Abstract Previous historical studies of the care of the insane in nineteenth century England have been based in the history of medicine. In this thesis, such care is placed in the context of the English poor law. The theory of the 1834 poor law was essentially silent on the treatment of the insane. That did not mean that developments in poor law had no effect only that the effects must be established by examination of administrative practices. To that end, this thesis focuses on the networks of administration of the poor law of lunacy, from 1834 to 1870. County asylums, a creation of the old (pre-1834) poor law, grew in numbers and scale only under the new poor law. While remaining under the authority of local Justices of the Peace, mid-century legislation provided an increasing role for local poor law staff in the admissions process. At the same time, workhouse care of the insane increased. Medical specialists in lunacy were generally excluded from local admissions decisions. The role of central commissioners was limited to inspecting and reporting; actual decision-making remained at the local level. The webs of influence between these administrators are traced, and the criteria they used to make decisions identified. The Leicestershire and Rutland Lunatic asylum provides a local study of these relations. Particular attention is given to admission documents and casebooks for those admitted to the asylum between 1861 and 1865. -

Fermanagh Genealogy Centre Leaflet Part 2

List of Civil Parishes in Fermanagh Aghalurcher, Aghavea, Belleek, Boho, Cleenish, Clogher, Clones, Currin, Derrybrusk, Derryvullan, Devenish, Drumkeeran, Drummully, Enniskillen, Galloon, Inishmacsaint, Killesher, Kinawley, Magheracross, Magheraculmoney, Rossory, Templecarn, Tomregan, Trory FERMANAGH There are over 2200 townlands in Fermanagh. genealogy centre Helping you find your Fermanagh roots Baronies of Fermanagh Irvinestown Belleek Enniskillen Lisnaskea Clanawley Clankelly Coole Knockninny Lurg Magheraboy Magherastephana Tirkennedy Fermanagh Genealogy Centre, Enniskillen Castle Enniskillen County Fermanagh BT74 7HL Email: [email protected] Phone: +44 (0) 28 66 323110 Designed & Printed by Ecclesville Printing Services | 028 8284 0048 www.epsni.com Printing Ltd Ecclesville by Designed & Printed SEARCHING FOR YOUR ANCESTORS Preserving Fermanagh’s Volunteers helping you find your genealogical heritage Fermanagh Roots WHO WE ARE AN OPPORTUNITY TO Fermanagh Genealogy Centre is run by BE A VOLUNTEER Volunteers. It was established in 2012 Volunteering for the Genealogy Centre and has operated as a delivery partner is an opportunity to make new friends for Fermanagh and Omagh District and to help others in their search for Council since October 2013 their family history connections to Fermanagh. It is also an opportunity WHAT WE ARE to learn more about how to search for We are a charitable organisation, who your own family history. We provide assist visitors to find their family history regular training for our volunteers, so connections in Fermanagh. Our aim is to that they are familiar with the range create a welcoming place for visitors and of material available. Opportunities exist Frank McHugh with visitors to the Fermanagh Genealogy volunteers for people to volunteer in the Centre on a Genealogy Centre, Dorothy McDonald volunteers, irrespective of religious, and her husband, Malcolm. -

Introduction Porter Papers

INTRODUCTION PORTER PAPERS November 2007 Porter Papers (D1390/10, N/19, LR1/178/1) Table of Contents Summary .................................................................................................................2 Family history...........................................................................................................3 The Belleisle estate .................................................................................................4 The townlands .........................................................................................................5 Fermanagh and Longford ........................................................................................6 Clogher Park............................................................................................................7 The 'Regency' period ...............................................................................................8 Railways and libel actions........................................................................................9 A scandalous affair ................................................................................................10 The Lisbellaw Gazette ...........................................................................................11 Other ventures .......................................................................................................12 Political affairs........................................................................................................13 Porter-Porter ..........................................................................................................14 -

Language Notes on Baronies of Ireland 1821-1891

Database of Irish Historical Statistics - Language Notes 1 Language Notes on Language (Barony) From the census of 1851 onwards information was sought on those who spoke Irish only and those bi-lingual. However the presentation of language data changes from one census to the next between 1851 and 1871 but thereafter remains the same (1871-1891). Spatial Unit Table Name Barony lang51_bar Barony lang61_bar Barony lang71_91_bar County lang01_11_cou Barony geog_id (spatial code book) County county_id (spatial code book) Notes on Baronies of Ireland 1821-1891 Baronies are sub-division of counties their administrative boundaries being fixed by the Act 6 Geo. IV., c 99. Their origins pre-date this act, they were used in the assessments of local taxation under the Grand Juries. Over time many were split into smaller units and a few were amalgamated. Townlands and parishes - smaller units - were detached from one barony and allocated to an adjoining one at vaious intervals. This the size of many baronines changed, albiet not substantially. Furthermore, reclamation of sea and loughs expanded the land mass of Ireland, consequently between 1851 and 1861 Ireland increased its size by 9,433 acres. The census Commissioners used Barony units for organising the census data from 1821 to 1891. These notes are to guide the user through these changes. From the census of 1871 to 1891 the number of subjects enumerated at this level decreased In addition, city and large town data are also included in many of the barony tables. These are : The list of cities and towns is a follows: Dublin City Kilkenny City Drogheda Town* Cork City Limerick City Waterford City Database of Irish Historical Statistics - Language Notes 2 Belfast Town/City (Co. -

About the Walks

WALKING IN FERMANAGH About the Walks The walks have been graded into four categories Easy Short walks generally fairly level going on well surfaced routes. Moderate Longer walks with some gradients and generally on well surfaced routes. Moderate/Difficult Some off road walking. Good footwear recommended. Difficult This only applies to Walk 20, a long walk only suitable for more experienced walkers correctly equipped. For those looking for a longer walk it is possible to combine some walks. These are numbers 10 and 11, 12 and 13, 18 and 20, and 24 and 25. Disclaimer Note: The maps used in this guide are taken from the original publication, published in 2000. Use of these maps is at your own risk. Bear in mind that the countryside is continually changing. This is especially true of forest areas, mainly due to the clearfelling programme. In the forests some of the footpaths may also change, either upgraded as funds become available or re-routed to overcome upkeep problems and reduce costs. These routes are not waymarked but should be by the summer of 2007. Metal barriers may well be repositioned or even removed. A new edition of the book, ‘25 Walks in Fermanagh’ will be coming out in the near future. please follow the principles of Leave No Trace Plan ahead and prepare Travel and camp on durable surfaces Dispose of waste properly Leave what you find Minimise campfire impacts Respect Wildlife Be considerate of other visitors WALKING IN FERMANAGH Useful Information This walking guide was commissioned by Fermanagh District Council who own the copyright of the text, maps, and associated photographs. -

62953 Erne Waterway Chart

waterways chart_lower 30/3/04 3:26 pm Page 1 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K 132 45678 GOLDEN RULES Lakeland Marine VORSICHT DRUMRUSH LODGE FOR CRUISING ON THE ERNE WATERWAY Niedrige Brücke. Durchfahrtshöhe 2.5M Use only long jetty H Teig Nur für kleine Boote MUCKROSS on west side of bay DANGER The Erne Waterway is not difficult to navigate, but there are some Golden Rules which MUST e’s R Harbour is too BE OBEYED AT ALL TIMES IF YOU ARE NOT TO RUN AGROUND or get into other trouble. Long Rock CAUTION shallow for cruisers Smith’s Rock ock Low bridge H.R 2.5m Fussweg H T KESH It must be appreciated that the Erne is a natural waterway and not dredged deep to the sides Small boats only Macart Is. Public footpath LOWER LOUGH ERNE like canal systems. In fact, the banks of the rivers and the shores of all the islands are normally P VERY SHALLOW a good way from the shore line and are quite often rocky! Bog Bay Fod Is. 350 H Rush Is. A47 Estea Island Pt. T Golden Rule No 1: NEVER CRUISE CLOSE TO THE SHORE (unless it is marked on the map Hare Island ross 5 LUSTY MORE uck that there is a good natural bank mooring). Keep more or less MID-STREAM wherever there A M Kesh River A 01234 Grebe WHITE CAIRN 8M are no markers, and give islands a very wide berth, at least 50-100 metres, unless there is a Black Bay BOA ISLAND 63C CAUTION Km x River mouth liable jetty on the island. -

Sunday 4Th July

The Sunday Newsletter Knockninny ST NINNIDH’S CHURCH DERRYLIN 4th July 2021 Fourteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time Fr. Gerard Alwill P.P. Phone no. 028 6774 8315 mobile 00353 872305557. parish email [email protected]. Mass Intentions: Sat 03 July: 8pm: Mary Flanagan (Faurkagh) AND Mary Ellen & John Shannon & deceased family members (Derrybrick) Sun 04 July: 11.15am: Josie Maguire (Mullyneeny) AND James & Anna Cassidy & deceased family members (Main St) Mon 05 July: 10am: Special Intention Tues 06 July: 10am: Special Intention Wed 07 July: 10am: Special Intention Thur 08 July: 10am: Special Intention Fri 09 July 10am: Special Intention Sat 10 July: 8pm: Seamus & Kathleen McBrien (Doon) Sun 11 July: 11.15am: Caolán Winterson (Knockninny Rock) Josie Donohue RIP: Please pray for the happy repose of the soul of Josie Donohoe, neé Gunn, London and formerly Corratrasna, who died on Thursday, 1st July. Josie was an aunt of Christopher Gunn, Corratrasna. Saturday 3rd July 8pm Reader – Cara Boyle Eucharistic Ministers: Lorraine McCaffrey Simon Kilgannon Sunday 4th July 11.15am: Reader – Maguire Family Eucharistic Ministers: Anne McBrien Tomas Scallon Saturday 10th July 8pm Reader – Ellen McCaffrey Eucharistic Ministers: Michelle Maguire Colette Cassidy Sunday 11th July 11.15am: Reader – Ella Clarke Eucharistic Ministers: Mary Mooney Laura Gunn Mass for Fr Boylan: A memorial Mass for Fr Noel Boylan will be celebrated in St Mary’s Church, Teemore, at 9.45 on Sunday, 11th July. St. Ninnidh's P.S Derrylin: The Staff, Pupils and Board of Governors of St. Ninnidh's P.S Derrylin would like to sincerely thank all our parents, pupils and community for their incredible support towards our Sponsored Walk fundraiser.