Whose Gob of Spit Is It?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elenco Film Dal 2015 Al 2020

7 Minuti Regia: Michele Placido Cast: Cristiana Capotondi, Violante Placido, Ambra Angiolini, Ottavia Piccolo Genere: Drammatico Distributore: Koch Media Srl Uscita: 03 novembre 2016 7 Sconosciuti Al El Royale Regia: Drew Goddard Cast: Chris Hemsworth, Dakota Johnson, Jeff Bridges, Nick Offerman, Cailee Spaeny Genere: Thriller Distributore: 20th Century Fox Uscita: 25 ottobre 2018 7 Uomini A Mollo Regia: Gilles Lellouche Cast: Mathieu Amalric, Guillaume Canet, Benoît Poelvoorde, Jean-hugues Anglade Genere: Commedia Distributore: Eagle Pictures Uscita: 20 dicembre 2018 '71 Regia: Yann Demange Cast: Jack O'connell, Sam Reid Genere: Thriller Distributore: Good Films Srl Uscita: 09 luglio 2015 77 Giorni Regia: Hantang Zhao Cast: Hantang Zhao, Yiyan Jiang Genere: Avventura Distributore: Mescalito Uscita: 15 maggio 2018 87 Ore Regia: Costanza Quatriglio Genere: Documentario Distributore: Cineama Uscita: 19 novembre 2015 A Beautiful Day Regia: Lynne Ramsay Cast: Joaquin Phoenix, Alessandro Nivola, Alex Manette, John Doman, Judith Roberts Genere: Thriller Distributore: Europictures Srl Uscita: 01 maggio 2018 A Bigger Splash Regia: Luca Guadagnino Cast: Ralph Fiennes, Dakota Johnson Genere: Drammatico Distributore: Lucky Red Uscita: 26 novembre 2015 3 Generations - Una Famiglia Quasi Perfetta Regia: Gaby Dellal Cast: Elle Fanning, Naomi Watts, Susan Sarandon, Tate Donovan, Maria Dizzia Genere: Commedia Distributore: Videa S.p.a. Uscita: 24 novembre 2016 40 Sono I Nuovi 20 Regia: Hallie Meyers-shyer Cast: Reese Witherspoon, Michael Sheen, Candice -

Wmc Investigation: 10-Year Analysis of Gender & Oscar

WMC INVESTIGATION: 10-YEAR ANALYSIS OF GENDER & OSCAR NOMINATIONS womensmediacenter.com @womensmediacntr WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER ABOUT THE WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER In 2005, Jane Fonda, Robin Morgan, and Gloria Steinem founded the Women’s Media Center (WMC), a progressive, nonpartisan, nonproft organization endeav- oring to raise the visibility, viability, and decision-making power of women and girls in media and thereby ensuring that their stories get told and their voices are heard. To reach those necessary goals, we strategically use an array of interconnected channels and platforms to transform not only the media landscape but also a cul- ture in which women’s and girls’ voices, stories, experiences, and images are nei- ther suffciently amplifed nor placed on par with the voices, stories, experiences, and images of men and boys. Our strategic tools include monitoring the media; commissioning and conducting research; and undertaking other special initiatives to spotlight gender and racial bias in news coverage, entertainment flm and television, social media, and other key sectors. Our publications include the book “Unspinning the Spin: The Women’s Media Center Guide to Fair and Accurate Language”; “The Women’s Media Center’s Media Guide to Gender Neutral Coverage of Women Candidates + Politicians”; “The Women’s Media Center Media Guide to Covering Reproductive Issues”; “WMC Media Watch: The Gender Gap in Coverage of Reproductive Issues”; “Writing Rape: How U.S. Media Cover Campus Rape and Sexual Assault”; “WMC Investigation: 10-Year Review of Gender & Emmy Nominations”; and the Women’s Media Center’s annual WMC Status of Women in the U.S. -

VES Goes Big for 'Hero,' 'Apes'

Search… Monday, June 22, 2015 News Resources Magazine Advertise Contact Shop Animag TV Galleries Calendar Home Festivals and Events VES Goes Big for ‘Hero,’ ‘Apes’ VES Goes Big for ‘Hero,’ ‘Apes’ Tom McLean Feb 4th, 2015 No Comments yet Like 0 Tweet 7 0 0 Share Email Print 0 The 13th annual VES Awards went ape for Apes and big for Big Hero 6 last night. Dawn of the Planet of the Apes lead the liveaction feature film categories Newsletter with three wins, while Disney’s animated feature Big Hero 6 took home the most awards overall with five. Subscribe to our Daily Newsletter In the TV categories, Game of Thrones came out on top, and SSE was email address Subscribe the mosthonored commercial. Here’s the full list of nominees, with the winners indicated in bold type. Congratulations to all the RSS Google Plus winners! Get updates Join our circle Outstanding Visual Effects in a Visual EffectsDriven Photoreal/Live Action Feature Motion Twitter Facebook Follow us Become our Picture fan Dawn of the Planet of the Apes. Joe Letteri, Ryan Stafford, Matt Kutcher, Dan Lemmon, Recent Posts Hannah Blanchini. Guardians of the Galaxy. Stephane Ceretti, Susan Pickett, Jonathan Fawkner, Nicolas Aithadi, Paul 'April,' 'Cosmos' Top Annecy Corbould. Awards Interstellar. Paul Franklin, Kevin Elam, Ann Podlozny, Andrew Lockley, Scott Fisher. June 21, 2015 0 Maleficent. Carey Villegas, Barrie Hemsley, Adam Valdez, Kelly Port, Michael Dawson. 'Inside Out' Opens to $91M, 2nd The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies. Joe Letteri, David Conley, Eric Saindon, Kevin to 'Jurassic' Juggernaut Sherwood, Steve Ingram. -

86Th Academy Awards

LIVE OSCARS SUNDAY March 2, 2014 7e|4p THE http://oscar.go.com/nominees OSCARS 86th Academy Awards Best Picture Actor–in a Leading Role Actress–in a Leading Role Actor–in a Supporting Role American Hustle Christian Bale “American Hustle” Amy Adams “American Hustle Barkhad Adbi “Captain Phillips” Captain Phillips Chiwetel Ejiofor “12 Years a Slave” Cate Blanchett “Blue Jasmine” Bradley Cooper “American Hustle” Dallas Buyers Club Bruce Dern “Nebraska” Sandra Bullock “Gravity” Michael Fassbender “12 Years a Slave” Gravity Leonardo DiCaprio “The Wolf of Wall Street Judi Dench “Philomena” Jonah Hill “The Wolf of Wall Street Her Matthew McConaughey “Dallas Buyers Club Meryl Streep “August: Osage County” Jared Leto “Dallas Buyers Club” Nebraska Philomena 12 Years a Slave The Wolf of Wall Street Actress–in a Supporting Role Animated Feature Film Cinematography Costume Design Sally Hawkins “Blue Jasmine” The Croods “The Grandmaster” Philippe Le Sourd “American Hustle” Michael Wilkinson Jennifer Lawrence “American Hustle” Despicable Me 2 “Gravity” Emmanuel Lubezki “The Grandmaster” William Chang Suk Ping Lupita Nyong’o “12 Years a Slave” Ernest and Celestine “Inside Llewyn Davis” Bruno Delbonnel “The Great Gatsby” Catherina Martin Julia Roberts “August: Osage County” Frozen “Nebraska” Phedon Papamichael “The Invisible Woman” Michael O’Connor June Squibb “Nebraska” The Wind Rises “Prisoners” Roger A. Deakins “12 Years a Slave” Patricia Norris Directing Documentary Feature Documentary Short Subject Film Editing “American Hustle” David O. Russell -

King Kong Went Through Animation

2 April 2008 designed a lot of the action sequences in the Oscar winner film. It was again not a simple process since there were a lot of conflicts of inteest on how to achieve the creative, hence we talks on the making of created an animated character. The footage of actual Guerrilla moments were taken from various zoos to perfect the facial system. Every motion capture shot in King Kong went through animation. Hence the King Kong MoCap has a very crucial role to play. The climax scene of the film, Christian Rivers joins a where King Kong dies, was well appreciated from all long list of illustrious visitors quarters of the industry and to Chennai based Animation wondered how the shot was and Visual Effects College - approached. It was a simple Image College of Arts, but a detailed approach when Animation & Technology we made the light in the pupil (ICAT). ICAT which offers of the eyes of King Kong Degree and Post Graduate diffused in other words we programs in Animation, made the audience to believe Visual Effects, Game Design by creating the dryness on the and Game programming has eyes to express it was dead." been bringing outstanding members from the Academic Apart from the character, and Professional segment to another amazing visual effects share their expertise with its shot in King Kong was the students. creation of New York City in 1933. A lot of research was Christian Rivers is an done in this regard, with Academy Award and BAFTA Seminar by "King Kong" maker Christian Rivers archival photographs being procured and winning New Zealand visual effects art many debates over the look of the creating buildings which were present only director and filmmaker. -

Final Copy 2020 06 23 Niu

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from Explore Bristol Research, http://research-information.bristol.ac.uk Author: Niu, Muqun Title: Digital visual effects in contemporary Hollywood cinema aesthetics, networks and transnational practice General rights Access to the thesis is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Public License. A copy of this may be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This license sets out your rights and the restrictions that apply to your access to the thesis so it is important you read this before proceeding. Take down policy Some pages of this thesis may have been removed for copyright restrictions prior to having it been deposited in Explore Bristol Research. However, if you have discovered material within the thesis that you consider to be unlawful e.g. breaches of copyright (either yours or that of a third party) or any other law, including but not limited to those relating to patent, trademark, confidentiality, data protection, obscenity, defamation, libel, then please contact [email protected] and include the following information in your message: •Your contact details •Bibliographic details for the item, including a URL •An outline nature of the complaint Your claim will be investigated and, where appropriate, the item in question will be removed from public view as soon as possible. This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from Explore Bristol Research, http://research-information.bristol.ac.uk Author: Niu, Muqun Title: DIGITAL VISUAL EFFECTS IN CONTEMPORARY HOLLYWOOD CINEMA AESTHETICS, NETWORKS AND TRANSNATIONAL PRACTICE General rights Access to the thesis is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Public License. -

The Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy & Horror

The Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy & Horror Films 334 West 54th Street Los Angeles, California 90037-3806 Phone: (323) 752-5811 e-mail: [email protected] Robert Holguin (President) Dr. Donald A. Reed (Founder) Publicity Contact: Karl Williams [email protected] (310) 493-3991 “Gravity” and “The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug” soar with 8 Saturn Award nominations, “The Hunger Games: Catching Fire,” scores with 7, “Iron Man 3,” “Pacific Rim,” “Star Trek Into Darkness and Thor: The Dark World lead with 5 nominations apiece for the 40th Annual Saturn Awards, while “Breaking Bad,” “Falling Skies,” and “Game of Thrones” lead on TV in an Epic Year for Science Fiction, Fantasy and Horror LOS ANGELES – February 26, 2014 – Alfonso Cuaron’s Gravity and Peter Jackson’s The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug both received 8 nominations as the Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy & Horror Films today announced nominations for the 40th Annual Saturn Awards, which will be presented in June. Other major contenders that received major nominations were The Hunger Games: Catching Fire, Guillermo del Toro’s Pacific Rim, Star Trek Into Darkness, The Book Thief, Her, Oz The Great anD Powerful and Ron Howard’s Rush. Also making a strong showing was the folk music fable InsiDe Llewyn Davis from Joel and Ethan Coen highlighting their magnificent and original work. And Scarlett Johansson was the first Best Supporting Actress to be nominated for her captivating vocal performance in Spike Jones’ fantasy romance Her. For the Saturn’s stellar 40th Anniversary celebration, two new categories have been added to reflect the changing times; Best Comic-to-Film Motion Picture will see Warner’s Man of Steel duking it out against Marvel’s Iron Man 3, Thor: The Dark WorlD and The Wolverine! The second new category is Best Performance by a Younger Actor in a Television Series – highlighting the most promising young talent working in TV today. -

89Th Oscars® Nominations Announced

MEDIA CONTACT Academy Publicity [email protected] January 24, 2017 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Editor’s Note: Nominations press kit and video content available here 89TH OSCARS® NOMINATIONS ANNOUNCED LOS ANGELES, CA — Academy President Cheryl Boone Isaacs, joined by Oscar®-winning and nominated Academy members Demian Bichir, Dustin Lance Black, Glenn Close, Guillermo del Toro, Marcia Gay Harden, Terrence Howard, Jennifer Hudson, Brie Larson, Jason Reitman, Gabourey Sidibe and Ken Watanabe, announced the 89th Academy Awards® nominations today (January 24). This year’s nominations were announced in a pre-taped video package at 5:18 a.m. PT via a global live stream on Oscar.com, Oscars.org and the Academy’s digital platforms; a satellite feed and broadcast media. In keeping with tradition, PwC delivered the Oscars nominations list to the Academy on the evening of January 23. For a complete list of nominees, visit the official Oscars website, www.oscar.com. Academy members from each of the 17 branches vote to determine the nominees in their respective categories – actors nominate actors, film editors nominate film editors, etc. In the Animated Feature Film and Foreign Language Film categories, nominees are selected by a vote of multi-branch screening committees. All voting members are eligible to select the Best Picture nominees. Active members of the Academy are eligible to vote for the winners in all 24 categories beginning Monday, February 13 through Tuesday, February 21. To access the complete nominations press kit, visit www.oscars.org/press/press-kits. The 89th Oscars will be held on Sunday, February 26, 2017, at the Dolby Theatre® at Hollywood & Highland Center® in Hollywood, and will be televised live on the ABC Television Network at 7 p.m. -

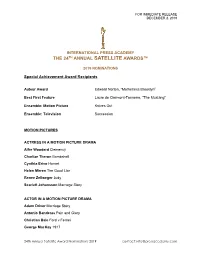

2019 IPA Nomination 24Th Satelilite FINAL 12-2-2019

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE DECEMBER 2, 2019 INTERNATIONAL PRESS ACADEMY THE 24TH ANNUAL SATELLITE AWARDS™ 2019 NOMINATIONS Special Achievement Award Recipients Auteur Award Edward Norton, “Motherless Brooklyn” Best First Feature Laure de Clermont-Tonnerre, “The MustanG” Ensemble: Motion Picture KnIves Out Ensemble: Television Succession MOTION PICTURES ACTRESS IN A MOTION PICTURE DRAMA Alfre Woodard Clemency Charlize Theron Bombshell Cynthia Erivo Harriet Helen Mirren The Good LIar Renee Zellweger Judy Scarlett Johansson MarriaGe Story ACTOR IN A MOTION PICTURE DRAMA Adam Driver MarriaGe Story Antonio Banderas PaIn and Glory Christian Bale Ford v FerrarI George MacKay 1917 24th Annual Satellite Award Nominations 2019 contact: [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE DECEMBER 2, 2019 Joaquin Phoenix Joker Mark Ruffalo Dark Waters ACTRESS IN A MOTION PICTURE, COMEDY OR MUSICAL Awkwafina The Farewell Ana De Armas KnIves Out Constance Wu Hustlers Julianne Moore GlorIa Bell ACTOR IN A MOTION PICTURE, COMEDY OR MUSICAL Adam Sandler Uncut Gems Daniel Craig KnIves Out Eddie Murphy DolemIte Is My Name Leonardo DiCaprio Once Upon a Time In Hollywood Taron Egerton Rocketman Taika Waititi Jojo RabbIt ACTRESS IN A SUPPORTING ROLE Jennifer Lopez Hustlers Laura Dern MarrIaGe Story Margot Robbie Bombshell Penelope Cruz PaIn and Glory Nicole Kidman Bombshell Zhao Shuzhen The Farewell ACTOR IN A SUPPORTING ROLE Anthony Hopkins The Two Popes Brad Pitt Once Upon a Time In Hollywood Joe Pesci The IrIshman Tom Hanks A BeautIful Day In The NeiGhborhood 24th Annual Satellite Award Nominations 2019 contact: [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE DECEMBER 2, 2019 Willem Dafoe The LIGhthouse Wendell Pierce BurnInG Cane MOTION PICTURE, DRAMA 1917 UnIversal PIctures Bombshell Lionsgate Burning Cane Array ReleasinG Ford v Ferrari TwentIeth Century Fox Joker Warner Bros. -

Lo Hobbit-La Desolazione Di Smaug PB-ITA

New Line Cinema e Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures Presentano Una Produzione Wingnuts Film Ian McKellen Martin Freeman Richard Armitage Benedict Cumberbatch Evangeline Lilly Lee Pace Luke Evans Ken Stott James Nesbitt e Orlando Bloom nel ruolo di ‘Legolas’ Musiche Howard Shore Co-prodotto da Philippa Boyens Eileen Moran Armi, Creature e Trucco Effetti Speciali Weta Workshop Ltd. Effetti visivi e animazioni Weta Digital Ltd. Supervisone Effetti Visivi Joe Lettieri Montaggio Jabez Olssen Scenografie Dan Hennah Direttore della fotografia Andrew Lesine Acs,Asc Produttori esecutivi Alan Horn Toby Emmerich Ken Kamis Carolyn Blackwood Prodotto da Carolynne Cunningham Zane Weiner Fran Walsh Peter Jackson Basato su un romanzo di J.R.R. Tolkien Sceneggiatura Fran Walsh Philippa Boyens Peter Jackson Guillermo Del Toro Diretto da Peter Jackson Durata: 2 ore e 41 minuti Sito: www.HobbitIlFilm.it FB: https://www.facebook.com/LoHobbitIlfilm Twitter: https://twitter.com/lohobbitfilm YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/warnerbrostrailers I materiali sono a disposizione sul sito “Warner Bros. Media Pass”, al seguente indirizzo: https://mediapass.warnerbros.com Dal 12 Dicembre al Cinema Distribuzione: WARNER BROS. ENTERTAINMENT ITALIA Ufficio Stampa Warner Bros. Entertainment Italia Riccardo Tinnirello: [email protected] Emanuela Semeraro: [email protected] Cinzia Fabiani: [email protected] Antonio Viespoli: [email protected] Dal regista premio Oscar® Peter Jackson arriva, “Lo Hobbit: La Desolazione di Smaug” il secondo film della trilogia dall’adattamento del popolare capolavoro senza tempo, The Hobbit, di J.R.R. Tolkien. I tre film narrano la storia ambientata nella Terra di Mezzo, 60 anni prima di “Il Signore degli Anelli” portato in scena sul grande schermo da Jackson e dal suo team, una trilogia campione d’incassi culminata con la vittoria dell’Oscar® di “Il Signore degli Anelli: Il Ritorno del Re”. -

89Th ACADEMY AWARDS® BALLOT

89th ACADEMY AWARDS® BALLOT Check out live results during the IMDb LIVE Viewing Party, an Academy Awards companion show, at 5 p.m. Feb. 26 on IMDb.com. Name ¨ B BEST ACHIEVEMENT BEST ACHIEVEMENT The Lobster 14 20 Yorgos Lanthimos and Efthymis Filippou IN COSTUME DESIGN IN VISUAL EFFECTS ¨ Manchester by the Sea ¨ Allied ¨ Deepwater Horizon Total Correct Kenneth Lonergan Joanna Johnston Craig Hammack, Jason H. Snell, ¨ 20th Century Women ¨ Fantastic Beasts and Jason Billington and Burt Dalton /24 Mike Mills Where to Find Them ¨ Doctor Strange Colleen Atwood Stephane Ceretti, Richard Bluff, BEST ADAPTED ¨ Florence Foster Jenkins Vincent Cirelli and Paul Corbould BEST MOTION PICTURE 08 01 Consolata Boyle ¨ OF THE YEAR SCREENPLAY The Jungle Book Robert Legato, Adam Valdez, ¨ Arrival ¨ Jackie ¨ Arrival Madeline Fontaine Andrew R. Jones and Dan Lemmon Shawn Levy, Dan Levine, Aaron Ryder Eric Heisserer ¨ La La Land ¨ Kubo and the Two Strings and David Linde ¨ Fences Mary Zophres Steve Emerson, Oliver Jones, Brian McLean ¨ August Wilson Fences and Brad Schiff Todd Black, Scott Rudin and Denzel Washington ¨ Hidden Figures Allison Schroeder and Theodore Melfi BEST ACHIEVEMENT IN ¨ Rogue One ¨ Hacksaw Ridge 15 John Knoll, Mohen Leo, Hal T. Hickel and ¨ Lion MAKEUP AND HAIRSTYLING Bill Mechanic and David Permut Neil Corbould Luke Davies ¨ ¨ Hell or High Water A Man Called Ove ¨ Moonlight Eva Von Bahr and Love Larson Carla Hacken and Julie Yorn BEST DOCUMENTARY Barry Jenkins and Tarell Alvin McCraney ¨ Star Trek Beyond 21 ¨ Hidden Figures FEATURE Peter -

Pietro Scalia for B~ *" MAN's Land (Bosnia-Herzegovina) Owen

ACHIEVEMENT IN SCIENTIFIC AND TECHNICAL AWARDS Pietro Scalia for B~ SCIENTIFIC AND ENGINEERING AWARD BEST FOREIGN lANGUAGE FILM (ACADEMY PLAQUE) MAN'S lAND (Bosnia-Herzegovina) *" To John M. Eargle, D. B. (Don) Keele and Mark E. Engebretson for the IEVEMEI\'T IN MAKEUP concept, design and engineering of the modern constant-directivi ty, direct radiator style motion picture loudspeaker systems. OWen and Richard Taylor for LORD OF THE RINGS: THE FELLOWSHIP OF THE RING To lain Neil for the concept and optical design and AI Saiki for the mechanical design of the Panavision Primo Macro Zoom Lens IN MUSIC (ORIGINAL SCORE) (PMZ). To Franz Kraus, Johannes Steurer and Wolfgana: Riedel for the design and development of the ARRILASER Film Recorder. To Peter Kuran for the invention , and Sean Coua:hlin, Joseph A. Olivier and William Conner for the engineering and development of the RCI-Color Film Restoration Process. To Makoto Tsukada, Shoji Kaneko and the Technical Staff of Imagica MIND (Brian Grazer, Ron Howard) Corporation, and Daijiro Fujie of N ikon Corporation for the engineering excellence and the impact on the motion picture A.l"liMATED SHORT FILM industry of the Imagica 65/35 Multi-Format Optical Printer. FOR THE BIRDS (Ralph Eggleston) To Steven Gerlach, Gregory Farrell and Christian Lurin for the design, BEST LTVE ACTION SHORT FILM engineering and implementation of the Kodak Panchromatic THE ACCOUNTANT (Ray McKinnon, Lisa Blount) Sound Recording Film. ACHIEVEMENT I SOUND To Paul J. Constantine and Peter M. Constantine for the design and