Philosophical Materialism Author(S): Colin Mcginn Source: Synthese, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adopted from Pdflib Image Sample

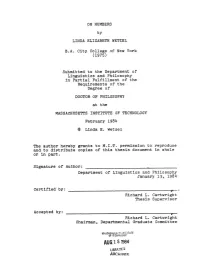

ON NUMBERS by LINDA ELIZABETH WETZEL B.A. City College of New York (1975) Submitted to the Department of Linguistics and Philosophy in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY February 1984 @ Linda E. Wetzel The author hereby grants to M.I.T. permission to reproduce and to distribute copies of this thesis document in whole or in part, Signature of Author: Department of Linguistics and Philosophy January 13, 1984 Certified by : .-_ - Richard L, Cartwright Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: v Richard L. Cartwright Chairman, Departmental Graduate Committee ON NUMBERS Linda E, Wetzel Submitted to the Department of Linguistics and Philosophy of October 21, 1983 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ABSTRACT We talk as though there are numbers. The view I defend, the "popularn view, has it that there -are numbers. However, since they clearly are not physical objects, we reason that they must be abstract ones. This suggests a realm of non-spatial non-temporal objects standing in numerical relations; arithmetic knowledge is then knowledge of this realm. But how do spatio~temporal creatures like ourselves come to have knowledge of this realm? The problem ("Benacerrafls probleni") can be avoided by arguing that there are no numbers. In "What Numbers Could Not Bew Benacerraf himself took such a route. In chapter one, I discuss three of Benacerrafls arguments, showing that the first is circular, that the second involves a consideration that can be explained by less drastic means than supposing there are no numbers, and that the third would, if successful, show that neither sets nor expressions exist either. -

Intrinsic Explanation and Field's Dispensabilist Strategy Sydney-Tilburg Conference on Reduction and the Special Sciences Russ

Intrinsic Explanation and Field’s Dispensabilist Strategy Sydney-Tilburg Conference on Reduction and the Special Sciences Russell Marcus Department of Philosophy, Hamilton College 198 College Hill Road Clinton NY 13323 [email protected] (315) 859-4056 (office) (315) 381-3125 (home) September 2007 ~2880 words Abstract: Philosophy of mathematics for the last half-century has been dominated in one way or another by Quine’s indispensability argument. The argument alleges that our best scientific theory quantifies over, and thus commits us to, mathematical objects. In this paper, I present new considerations which undermine the most serious challenge to Quine’s argument, Hartry Field’s reformulation of Newtonian Gravitational Theory. Intrinsic Explanation, Page 1 §1: Introduction Quine argued that we are committed to the existence mathematical objects because of their indispensable uses in scientific theory. In this paper, I defend Quine’s argument against the most popular objection to it, that we can reformulate science without reference to mathematical objects. I interpret Quine’s argument as follows:1 (QIA) QIA.1: We should believe the theory which best accounts for our empirical experience. QIA.2: If we believe a theory, we must believe in its ontic commitments. QIA.3: The ontic commitments of any theory are the objects over which that theory first-order quantifies. QIA.4: The theory which best accounts for our empirical experience quantifies over mathematical objects. QIA.C: We should believe that mathematical objects exist. An instrumentalist may deny either QIA.1 or QIA.2, or both. Regarding QIA.1, there is some debate over whether we should believe our best theories. -

Robert C. Koons

ROBERT C. KOONS ADDRESSES Department of Philosophy 1, University Station C3500 University of Texas at Austin Austin, Texas 78712-3500 (512) 471-5530 [email protected] EDUCATION 1979 B.A., Philosophy, Michigan State University, Summa cum laude 1981 B.A., Philosophy and Theology, Oxford University First Class Honours 1987 Ph.D., Philosophy, UCLA AREAS OF SPECIALIZATION Metaphysics and Epistemology Philosophical Logic Philosophy of Religion PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Sept. 1, 2000 Professor, University of Texas at Austin 1993-2000 Associate Professor, University of Texas at Austin 1987-1993 Assistant Professor, University of Texas at Austin HONORS Visiting Scholar, Nanjing University, April/May 2007 Philosopher-in-Residence, Valparaiso University, Spring 2001 Gustave O. Arlt Award (Council of Graduate Schools) 1992 Carnap Prize (UCLA) 1987 Richard M. Weaver Fellow, 1985-87 Danforth Fellow, l979-85 Dillistone Scholar (Oriel College, Oxford), l980 Marshall Scholar, l979-1981 ROBERT C. KOONS PAGE 2 RESEARCH GRANTS National Science Foundation, Division of Information, Robotics and Intelligent Systems, "The Logic and Representation of Properties and Propositions for Computer Natural Language Processing," with Kamp, Bonevac, Asher, and C. Smith, 1988-1989. National Research Council Travel Grant for Attendance of the Ninth International Congress on Logic, Methodology and Philosophy of Science, Uppsala, Sweden, 1991. Faculty Research Assignment, "The Logic of Causation and Teleological Function," Spring 1997. Visiting Scholar, Institute for Advanced -

Realism and Anti-Realism in Mathematics

REALISM AND ANTI-REALISM IN MATHEMATICS The purpose of this essay is (a) to survey and critically assess the various meta- physical views - Le., the various versions of realism and anti-realism - that people have held (or that one might hold) about mathematics; and (b) to argue for a particular view of the metaphysics of mathematics. Section 1 will provide a survey of the various versions of realism and anti-realism. In section 2, I will critically assess the various views, coming to the conclusion that there is exactly one version of realism that survives all objections (namely, a view that I have elsewhere called full-blooded platonism, or for short, FBP) and that there is ex- actly one version of anti-realism that survives all objections (namely, jictionalism). The arguments of section 2 will also motivate the thesis that we do not have any good reason for favoring either of these views (Le., fictionalism or FBP) over the other and, hence, that we do not have any good reason for believing or disbe- lieving in abstract (i.e., non-spatiotemporal) mathematical objects; I will call this the weak epistemic conclusion. Finally, in section 3, I will argue for two further claims, namely, (i) that we could never have any good reason for favoring either fictionalism or FBP over the other and, hence, could never have any good reason for believing or disbelieving in abstract mathematical objects; and (ii) that there is no fact of the matter as to whether fictionalism or FBP is correct and, more generally, no fact of the matter as to whether there exist any such things as ab- stract objects; I will call these two theses the strong epistemic conclusion and the metaphysical conclusion, respectively. -

Jared Warren

JARED WARREN Curriculum Vitae B [email protected] T 904.866.8439 www.jaredwarren.org Education 2015 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PhD in Philosophy COMMITTEE: David Chalmers, Hartry Field (chair), Crispin Wright Areas of Specialization Mind and Language, Metaphysics and Epistemology, Mathematics and Logic Areas of Competence History of Analytic Philosophy, Metaethics, Philosophy of Science Publications (1) “The Possibility of Truth by Convention”(2015) The Philosophical Quarterly 65(258): 84-93. (2) “Quantifier Variance and the Collapse Argument” (2015) The Philosophical Quarterly 65(259): 241-253. (3) “Conventionalism, Consistency, and Consistency Sentences” (2015) Synthese 192(5): 1351-1371. (4) “Talking with Tonkers” (2015) Philosophers’ Imprint 15(24): 1-24. (5) “Trapping the Metasemantic Metaphilosophical Deflationist?” (2016) Metaphilosophy 47(1): 108-121. (6) “Sider on the Epistemology of Structure” (2016) Philosophical Studies 173(9): 2417-2435. (7) “Epistemology vs Non-Causal Realism” (2017) Synthese 194(5): 1643-1662. (8) “Revisiting Quine on Truth by Convention” (2017) The Journal of Philosophical Logic 46(2): 119-139. 1 (9) “Internal and External Questions Revisited” (2016) The Journal of Philosophy 113(4): 177-209. (10) “Change of Logic, Change of Meaning” (forthcoming) Philosophy & Phenomenological Research. (11) “Quantifier Variance and Indefinite Extensibility” (2017) The Philosophical Review 126(1): 81-122. (12) “A Metasemantic Challenge for Mathematical Determinacy” (forthcoming) Synthese. (with Daniel Waxman) (13) “Quantifier Variance -

Adopted from Pdflib Image Sample

1 WITH REFERENCE TO TRUTH: STI~IES IN REFERENTIAL SEMANTICS by DOUGLAS FILLMORE CANNON A.B., Harvard University 1973 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS AND PHILOSOPHY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in PHILOSOPHY at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 1982 <e> Douglas Fillmore Cannon 1982 The author hereby grants to M.I.T. permission to reproduce and to dis tribute publicly copies of this thesis document in ~hole or in part. Signature of Author__________~-.;~~~---•. ~....;;;""",,---.::l----- Certified by------------------__._1r--------- I < George Boolas Thesis Supervisor Accepted by aL~ «) ~"0 ~ilijarvis Thomson MA5~HUS~~fl~I~~~artment Graduate Committee OF TEtHNOlOSY Archives JUL 8 1982 2 WITH REFERENCE TO TRUTH: STUDIES IN REFERENTIAL SEMANTICS by DOUGLAS FILLMORE CANNON Submitted to the Department of Linguistics and Philosophy on April 8, 1982, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Philosophy ABSTRACT In the first parts of my thesis I explore two philosophical programs in the area of referential semantics, namely, rigid designation accounts of proper names and naturalistic theories of truth. I conclude with an inquiry into the theory of truth for mathematics and its relationship to mathematical Platonism. In Part One, I confront Kripke's well-known views with Quine's pro posal that proper names correspond to a kind of predicate. I argue that the belief that proper names are rigid designators is unjustified and that many questions about the reference of terms in various possible worlds have no determinate answer. I take issue with Kripke's emphasis on the question, "How is the reference of names determined?", and suggest that it reflects dubious philosophical presuppositions. -

Chris Scambler

Chris Scambler New York University Phone: +1 (929) 422-9674 Department of Philosophy Email: [email protected] 5 Washington Place Web: https://chrisjscambler.com New York, NY 10003 United States Areas of specialization Logic, Foundations of Mathematics Areas of competence Metaphysics, Philosophy of Physics, Philosophy of Mind Publications Forth. \Transfinite Meta-inferences": Journal of Philosophical Logic Forth. \A Justification for the Quantificational Hume Principle": Erkenntnis Forth. “Ineffability and Revenge": Review of Symbolic Logic 2020 \Classical Logic and the Strict Tolerant Hierarchy", 49, 351-370: Journal of Philosophical Logic 2020 \An Indeterminate Universe of Sets" 197, 545-573: Synthese Education 2015 - present Ph.D. in Philosophy, New York University. Dissertation title: Was the Cantorian Turn Rationally Required? Committee: Hartry Field (chair), Kit Fine, Graham Priest, Crispin Wright August 2019 Visiting Scholar, University of Oslo (ConceptLab, funded fellowship) July 2016 Visiting Scholar, University of Vienna (Kurt G¨odelResearch Center, funded fellowship) 2014 - 2015 M.Res in Philosophy, Birmingham University. Dissertation title: An indeterminate universe of sets. 2012 - 2014 Conversion MA in Philosophy, Birkbeck College, University of London. 1 Presentations Aug 2020 Comments on Button and Walsh's `Philosophy of Model Theory', European Congress of Analytic Philosophy (invited) Feb 2020 \Categoricity and Determinacy", workshop on Structuralist Foundations, University of Vienna (invited) July 2019 \Can All Things Be -

Philosophy of Language and Mind: 1950-1990 Author(S): Tyler Burge Source: the Philosophical Review, Vol

Philosophical Review Philosophy of Language and Mind: 1950-1990 Author(s): Tyler Burge Source: The Philosophical Review, Vol. 101, No. 1, Philosophy in Review: Essays on Contemporary Philosophy (Jan., 1992), pp. 3-51 Published by: Duke University Press on behalf of Philosophical Review Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2185043 Accessed: 11-04-2017 02:19 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2185043?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Philosophical Review, Duke University Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Philosophical Review This content downloaded from 128.97.244.236 on Tue, 11 Apr 2017 02:19:01 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms The Philosophical Review, Vol. 101, No. 1 January 1992) Philosophy of Language and Mind: 1950-1990 Tyler Burge The last forty years in philosophy of language and philosophy of mind have seen, I hazard to say, some of the most intense and intellectually powerful discussion in any academic field during the period.' Yet the achievements in these areas have not been widely appreciated by the general intellectual public. -

Recent Debates About the a Priori Hartry Field

Recent Debates About the A Priori Hartry Field 1. Background. New York University 1. Background. At least from the time of the ancient Greeks, most philosophers have held that some of our knowledge is independent of experience, or “a priori”. Indeed, a major tenet of the rationalist tradition in philosophy was that a great deal of our knowledge had this character: even Kant, a critic of some of the overblown claims of rationalism, thought that the structure of space could be known a priori, as could many of the fundamental principles of physics; and Hegel is reputed to have claimed to have deduced on a priori grounds that the number of planets is exactly five. There was however a strong alternative tradition, empiricism, which was skeptical of our ability to know such things completely independent of experience. For the most part this tradition did not deny the existence of a priori knowledge altogether, since mathematics and logic and a few other things seemed knowable a priori; but it did try to drastically limit the scope of a priori knowledge, to what Hume called “relations of ideas” (as opposed to “matters of fact”) and what came later to be called “analytic” (as opposed to “synthetic”) truths. A priori knowledge of analytic truths was thought unpuzzling, because it seemed to admit a deflationary explanation: if mathematical claims just stated “relations among our ideas” rather than “matters of fact”, our ability to know them independent of experience seemed unsurprising. So, up until the mid-20th century, a major tenet of the empiricism was that there can be no a priori knowledge of synthetic (non-analytic) truths. -

Intrinsic Explanation and Field's Dispensabilist Strategy

International Journal of Philosophical Studies, 2013 Vol. 21, No. 2, 163–183, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09672559.2012.727011 Intrinsic Explanation and Field’s Dispensabilist Strategy Russell Marcus Abstract Hartry Field defended the importance of his nominalist reformulation of Newtonian Gravitational Theory, as a response to the indispensability argument, on the basis of a general principle of intrinsic explanation. In this paper, I argue that this principle is not sufficiently defensible, and can not do the work for which Field uses it. I argue first that the model for Field’s reformulation, Hilbert’s axiomatization of Euclidean geometry, can be understood without appealing to the principle. Second, I argue that our desires to unify our theories and explanations undermines Field’s principle. Third, the claim that extrinsic theories seem like magic is, in this case, really just a demand for an account of the applications of mathematics in science. Finally, even if we were to accept the principle, it would not favor the fictionalism that motivates Field’s argument, since the indispensabilist’s mathematical objects are actually intrinsic to scientific theory. Keywords: philosophy of mathematics; indispensability argument; Hartry Field; intrinsic explanation 1. Overview Quine argued that we should believe that mathematical objects exist because of their indispensable uses in scientific theory. Hartry Field rejects Quine’s argument, arguing that we can reformulate science with- out referring to mathematical objects. Field provided a precedental reformulation of Newtonian Gravitational Theory (NGT) which has been refined, improved, and extended in the years since his original monograph. In this paper, I argue that Field’s impressive construction and its extension do not impugn Quine’s argument in the way that Field alleges that they do. -

What Is the Benacerraf Problem?

Chapter 2 What Is the Benacerraf Problem? Justin Clarke-Doane In “Mathematical Truth,” Paul Benacerraf presented an epistemological problem for mathematical realism. “[S]omething must be said to bridge the chasm, created by […] [a] realistic […] interpretation of mathematical propositions… and the human knower,” he writes.1 For prima facie “the connection between the truth conditions for the statements of [our mathematical theories] and […] the people who are supposed to have mathematical knowledge cannot be made out.”2 The problem presented by Benacerraf—variously called “the Benacerraf Problem” the “Access Problem,” the “Reliability Challenge,” and the “Benacerraf-Field Challenge”—has largely shaped the philosophy of mathematics. Realist and antirealist views have been defined in reaction to it. But the influence of the Benacerraf Problem is not remotely limited to the philosophy of mathematics. The problem is now thought to arise in a host of other areas, including meta-philosophy. The following quotations are representative. The challenge for the moral realist […] is to explain how it would be anything more than chance if my moral beliefs were true, given that I do not interact with moral properties. […] [T]his problem is not specific to moral knowledge. […] Paul Benacerraf originally raised it as a problem about mathematics. Huemer (2005: 99)3 It is a familiar objection to […] modal realism that if it were true, then it would not be possible to know any of the facts about what is […] possible […]. This epistemological Thanks to Dan Baras, David James Barnett, Michael Bergmann, John Bigelow, John Bengson, Sinan Dogramaci, Hartry Field, Toby Handfield, Lloyd Humberstone, Colin Marshall, Josh May, Jennifer McDonald, Jim Pryor, Juha Saatsi, Josh Schechter, and to audiences at Australian National University, Monash University, La Trobe University, UCLA, the University of Melbourne, the University of Nottingham, the Institut d’Histoire et de Philosophie des Sciences et des Techniques and the University of Sydney for helpful comments. -

Hilary Putnam: an Era of Philosophy Has Ended

Hilary Putnam: An Era of Philosophy Has Ended Sanjit Chakraborty Philosophia Philosophical Quarterly of Israel ISSN 0048-3893 Philosophia DOI 10.1007/s11406-016-9760-5 1 23 Your article is protected by copyright and all rights are held exclusively by Springer Science +Business Media Dordrecht. This e-offprint is for personal use only and shall not be self- archived in electronic repositories. If you wish to self-archive your article, please use the accepted manuscript version for posting on your own website. You may further deposit the accepted manuscript version in any repository, provided it is only made publicly available 12 months after official publication or later and provided acknowledgement is given to the original source of publication and a link is inserted to the published article on Springer's website. The link must be accompanied by the following text: "The final publication is available at link.springer.com”. 1 23 Author's personal copy Philosophia DOI 10.1007/s11406-016-9760-5 Hilary Putnam: An Era of Philosophy Has Ended Sanjit Chakraborty1 Received: 18 April 2016 /Revised: 30 July 2016 /Accepted: 6 September 2016 # Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2016 Leading philosophy towards constant dynamic expeditions and holding on to an incredible style of self-critique, Hilary Putnam (1926–2016), over the five decades, has been in the process of making laudable contributions in philosophy and philosophy of science by being a beacon to a series of philosophical generations. He was a profound scholar full of wisdom, morality and love of humanity, in a word a ‘Philos- opher’sPhilosopher’.