Milton and Jacob Böhme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

140 Roger Bacon and the Hermetic Tradition in Medieval Science

Roger Bacon and the Hermetic Tradition in Medieval Science GEORGE MOLLAND Roger Bacon would no more have wished to be called a Hermeticist than to be called a magician. For him magic was by its very nature bad, but this did not stop him from indulging beliefs and practices that bordered on the magical. Similarly, although he had no great or very favourable image of Hermes Trismegistus, his writings are infused with a spirit akin to what in a loose understanding of the term have been called Hermetic trends in Renaissance thought, and especially to the ` `Hermetic Tradition in Renaissance Science" .1 1 In exciting scholarship dating back some thirty years and more, a group of scholars, some closely associated with the Warburg Institute in London, demonstrated the vitality in Renaissance thought of quasi- magical traditions associated (sometimes rather remotely) with writings attributed to the supposed ancient Egyptian sage Hermes Trismegistus, and urged their importance for a proper historical assessment of the nascent Scientific Revolution.2 The impact made by these studies has produced the impression that "Hermetic" influences upon science were in essence a Renaissance phenomenon and had I The phrase is from Frances A. Yates' oft-cited article, The Hermetic Tradition in RenaissanceScience, in: Art, Science, and History in the Renaissance, ed. Charles S. Singleton, Baltimore 1968, 255-74, reprinted in F. A. Yates, Ideas and Ideals in the North EuropeanRenaissance.- Collected Essays, VolumeIII, London 1984, 227-46. 2 Among important writings in this genre, together with some more critical of it, I cite here: F. A. Yates, GiordanoBruno and the HermeticTradition, London 1964; id., The RosicrucianEnlightenment, London 1972; D. -

Geometry, Mathematics, and Dialectic Beyond Aristotelian Science

Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 40 (2009) 243–257 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Studies in History and Philosophy of Science journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/shpsa Francesco Patrizi’s two books on space: geometry, mathematics, and dialectic beyond Aristotelian science Amos Edelheit De Wulf-Mansion Centre for Ancient, Medieval, and Renaissance Philosophy, Institute of Philosophy, Catholic University of Louvain, Kardinaal Mercierplein 2, BE-3000 Leuven, Belgium article info abstract Keywords: Francesco Patrizi was a competent Greek scholar, a mathematician, and a Neoplatonic thinker, well Francesco Patrizi known for his sharp critique of Aristotle and the Aristotelian tradition. In this article I shall present, in Space the first part, the importance of the concept of a three-dimensional space which is regarded as a body, Geometry as opposed to the Aristotelian two-dimensional space or interval, in Patrizi’s discussion of physical space. Mathematics This point, I shall argue, is an essential part of Patrizi’s overall critique of Aristotelian science, in which Aristotle Epicurean, Stoic, and mainly Neoplatonic elements were brought together, in what seems like an original Proclus theory of space and a radical revision of Aristotelian physics. Moreover, I shall try to show Patrizi’s dia- lectical method of definition, his geometrical argumentation, and trace some of the ideas and terms used by him back to Proclus’ Commentary on Euclid. This text of Proclus, as will be shown in the second part of the article, was also important for Patrizi’s discussion of mathematical space, where Patrizi deals with the status of mathematics and redefines some mathematical concepts such as the point and the line accord- ing to his new theory of space. -

Alchemical Culture and Poetry in Early Modern England

Alchemical culture and poetry in early modern England PHILIP BALL Nature, 4–6 Crinan Street, London N1 9XW, UK There is a longstanding tradition of using alchemical imagery in poetry. It first flourished at the end of the sixteenth century, when the status of alchemy itself was revitalised in European society. Here I explain the reasons for this resurgence of the Hermetic arts, and explore how it was manifested in English culture and in particular in the literary and poetic works of the time. In 1652 the English scholar Elias Ashmole published a collection of alchemical texts called Theatrum Chymicum Britannicum, comprising ‘Several Poeticall Pieces of Our Most Famous English Philosophers’. Among the ‘chemical philosophers’ represented in the volume were the fifteenth-century alchemists Sir George Ripley and Thomas Norton – savants who, Ashmole complained, were renowned on the European continent but unduly neglected in their native country. Ashmole trained in law, but through his (second) marriage to a rich widow twenty years his senior he acquired the private means to indulge at his leisure a scholarly passion for alchemy and astrology. A Royalist by inclination, he had been forced to leave his London home during the English Civil War and had taken refuge in Oxford, the stronghold of Charles I’s forces. In 1677 he donated his impressive collection of antiquities to the University of Oxford, and the building constructed to house them became the Ashmolean, the first public museum in England. Ashmole returned to London after the civil war and began to compile the Theatrum, which was intended initially as a two-volume work. -

GIORDANO BRUNO: a FINE BIBLIOPHILE the Love for Books and Libraries of a Great Philosopher ______

GIORDANO BRUNO: A FINE BIBLIOPHILE The love for books and libraries of a great philosopher __________________________ GUIDO DEL GIUDICE he life and destiny living in a convent involved t of Giordano Bruno lack of discipline, vices, are closely linked to murders and punishments, it books. His extraordinary desire was not hard getting the for knowledge and for prohibited books from the spreading his ideas led to a library. Because of the particular and privileged continuous coming and going relationship with books, which of books and the several thefts, accompanied him since his as the General Master of the youth. One can easily say that Dominican Order pointed out, the main reason that led him to in 1571 Pope Pius V had joining the convent of St. published a “Breve”, in which Domenico was the fact that he he declared that whoever stole could get access to the well- or took, for whatever reason, equipped library of the any book from the Libraria, convent, which would quench without a clear licence of the his omnivorous hunger for Venetian edition of Aristotle's Pope or the General Master, knowledge, help him De Anima (1562) would be excommunicated1. developing his exceptional mnemonic skills This decision was written on a stone, which and feed that ingenious naturalistic and has now disappeared, inserted in the right infinitistic afflatus, which he strongly felt. But wall of the little hall which gives access to the this passion itself put him in danger. As he Library. This detail, which many had not said during the interrogations in Venice, he noticed, determined the final departure of the was first censored “because I asked one of the Nolan from his home land. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 10 February 2011 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Banks, K.. (2007) 'Space and light : cinian neoplatonism and Jacques Peletier Du Mans's 'Amour des Amours'.', Biblioth equed'humanisme et renaissance., 69 (1). pp. 83-101. Further information on publisher's website: http://www.droz.org/fr/livre/?GCOI=26001100835230 Publisher's copyright statement: Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Space and Light: Ficinian Neoplatonism and Jacques Peletier Du Mans’s Amour des amours Jacques Peletier Du Mans‟s Amour des amours of 1555 uses the fiction of a cosmic voyage inspired by love in order to join together a collection of love poems with a series of meteorological and planetary ones: the latter represent the poet‟s discoveries upon flying into the cosmos -

Gold and Silver: Perfection of Metals in Medieval and Early Modern Alchemy Citation: F

Firenze University Press www.fupress.com/substantia Gold and silver: perfection of metals in medieval and early modern alchemy Citation: F. Abbri (2019) Gold and sil- ver: perfection of metals in medieval and early modern alchemy. Substantia 3(1) Suppl.: 39-44. doi: 10.13128/Sub- Ferdinando Abbri stantia-603 DSFUCI –Università di Siena, viale L. Cittadini 33, Il Pionta, Arezzo, Italy Copyright: © 2019 F. Abbri. This is E-mail: [email protected] an open access, peer-reviewed article published by Firenze University Press (http://www.fupress.com/substantia) Abstract. For a long time alchemy has been considered a sort of intellectual and histo- and distributed under the terms of the riographical enigma, a locus classicus of the debates and controversies on the origin of Creative Commons Attribution License, modern chemistry. The present historiography of science has produced new approach- which permits unrestricted use, distri- es to the history of alchemy, and the alchemists’ roles have been clarified as regards the bution, and reproduction in any medi- vicissitudes of Western and Eastern cultures. The paper aims at presenting a synthetic um, provided the original author and profile of the Western alchemy. The focus is on the question of the transmutation of source are credited. metals, and the relationships among alchemists, chymists and artisans (goldsmiths, sil- Data Availability Statement: All rel- versmiths) are stressed. One wants to emphasise the specificity of the history of alche- evant data are within the paper and its my, without any priority concern about the origins of chemistry. Supporting Information files. Keywords. History of alchemy, precious metals, transmutation of metals. -

THE INVENTION of ATOMIST ICONOGRAPHY 1. Introductory

THE INVENTION OF ATOMIST ICONOGRAPHY Christoph Lüthy Center for Medieval and Renaissance Natural Philosophy University of Nijmegen1 1. Introductory Puzzlement For centuries now, particles of matter have invariably been depicted as globules. These glob- ules, representing very different entities of distant orders of magnitudes, have in turn be used as pictorial building blocks for a host of more complex structures such as atomic nuclei, mole- cules, crystals, gases, material surfaces, electrical currents or the double helixes of DNA. May- be it is because of the unsurpassable simplicity of the spherical form that the ubiquity of this type of representation appears to us so deceitfully self-explanatory. But in truth, the spherical shape of these various units of matter deserves nothing if not raised eyebrows. Fig. 1a: Giordano Bruno: De triplici minimo et mensura, Frankfurt, 1591. 1 Research for this contribution was made possible by a fellowship at the Max-Planck-Institut für Wissenschafts- geschichte (Berlin) and by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO), grant 200-22-295. This article is based on a 1997 lecture. Christoph Lüthy Fig. 1b: Robert Hooke, Micrographia, London, 1665. Fig. 1c: Christian Huygens: Traité de la lumière, Leyden, 1690. Fig. 1d: William Wollaston: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, 1813. Fig. 1: How many theories can be illustrated by a single image? How is it to be explained that the same type of illustrations should have survived unperturbed the most profound conceptual changes in matter theory? One needn’t agree with the Kuhnian notion that revolutionary breaks dissect the conceptual evolution of science into incommensu- rable segments to feel that there is something puzzling about pictures that are capable of illus- 2 THE INVENTION OF ATOMIST ICONOGRAPHY trating diverging “world views” over a four-hundred year period.2 For the matter theories illustrated by the nearly identical images of fig. -

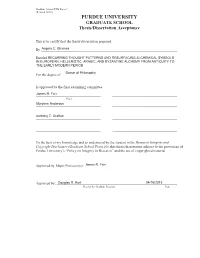

PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Thesis/Dissertation Acceptance

Graduate School ETD Form 9 (Revised 12/07) PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Thesis/Dissertation Acceptance This is to certify that the thesis/dissertation prepared By Angela C. Ghionea Entitled RECURRING THOUGHT PATTERNS AND RESURFACING ALCHEMICAL SYMBOLS IN EUROPEAN, HELLENISTIC, ARABIC, AND BYZANTINE ALCHEMY FROM ANTIQUITY TO THE EARLY MODERN PERIOD Doctor of Philosophy For the degree of Is approved by the final examining committee: James R. Farr Chair Myrdene Anderson Anthony T. Grafton To the best of my knowledge and as understood by the student in the Research Integrity and Copyright Disclaimer (Graduate School Form 20), this thesis/dissertation adheres to the provisions of Purdue University’s “Policy on Integrity in Research” and the use of copyrighted material. Approved by Major Professor(s): ____________________________________James R. Farr ____________________________________ Approved by: Douglas R. Hurt 04/16/2013 Head of the Graduate Program Date RECURRING THOUGHT PATTERNS AND RESURFACING ALCHEMICAL SYMBOLS IN EUROPEAN, HELLENISTIC, ARABIC, AND BYZANTINE ALCHEMY FROM ANTIQUITY TO THE EARLY MODERN PERIOD A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University by Angela Catalina Ghionea In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 Purdue University West Lafayette, Indiana UMI Number: 3591220 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3591220 Published by ProQuest LLC (2013). -

Historical Influence of the Rosicrucian Fraternity on Freemasonry

Historical Influence of the Rosicrucian Fraternity on Freemasonry Introduction Freemasonry has a public image that sometimes includes notions that we practice some sort of occultism, alchemy, magic rituals, that sort of thing. As Masons we know that we do no such thing. Since 1717 we have been a modern, rational, scientifically minded craft, practicing moral and theological virtues. But there is a background of occult science in Freemasonry, and it is related to the secret fraternity of the Rosicrucians. The Renaissance Heritage1 During the Italian renaissance of the 15th century, scholars rediscovered and translated classical texts of Plato, Pythagoras, and the Hermetic writings attributed to Hermes Trismegistus, thought to be from ancient Egypt. Over the next two centuries there was a widespread growth in Europe of various magical and spiritual practices – magic, alchemy, astrology -- based on those texts. The mysticism and magic of Jewish Cabbala was also studied from texts brought from Spain and the Muslim world. All of these magical practices had a religious aspect, in the quest for knowledge of the divine order of the universe, and Man’s place in it. The Hermetic vision of Man was of a divine soul, akin to the angels, within a material, animal body. By the 16th century every royal court in Europe had its own astrologer and some patronized alchemical studies. In England, Queen Elizabeth had Dr. John Dee (1527- 1608) as one of her advisors and her court astrologer. Dee was also an alchemist, a student of the Hermetic writings, and a skilled mathematician. He was the most prominent practitioner of Cabbala and alchemy in 16th century England. -

Grounding the Angels

––––––––––––––––––––––– Grounding the Angels: An attempt to harmonise science and spiritism in the celestial conferences of John Dee ––––––––––––––––––––––– A thesis submitted by Annabel Carr to the Department of Studies in Religion in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts (Honours) University of Sydney ––––––––––––– Supervised by Dr Carole Cusack June, 2006 Acknowledgements Thank you to my darling friends, sister and cousin for their treasurable support. Thank you to my mother for her literary finesse, my father for his technological and artistic ingenuity, and my parents jointly for remaining my most ardent and loving advocates. Thank you to Dominique Wilson for illuminating the world of online journals and for her other kind assistance; to Robert Haddad of the Sydney University Catholic Chaplaincy Office for his valuable advice on matters ecclesiastical; to Sydney University Inter-Library Loans for sourcing rare and rarefied material; and to the curators of Early English Books Online and the Rare Books Library of Sydney University for maintaining such precious collections. Thank you to Professor Garry Trompf for an intriguing Honours year, and to each member of the Department of Studies in Religion who has enriched my life with edification and encouragement. And thank you most profoundly to Dr Carole Cusack, my thesis supervisor and academic mentor, for six years of selfless guidance, unflagging inspiration, and sagacious instruction. I remain forever indebted. List of Illustrations Figure 1. John Dee’s Sigillum Dei Ameth, recreated per Sloane MS. 3188, British Museum Figure 2. Edward Kelley, Ebenezer Sibly, engraving, 1791 Figure 3. The Archangel Leaving the Family of Tobias, Rembrandt, oil on canvas, 1637 Figure 4. -

UNDERGRADUATE STUDY PROGRAMME Philosophy (Double-Major)

UNIVERSITYOFSPLIT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES UNDERGRADUATE STUDY PROGRAMME Philosophy (double-major) Class: 602-04/16-02/0002 Reg. No: 2181-190-02-2/1-16-0002 Split, December 2015 Undergraduate study programme Philosophy (double major) 1 GENERAL INFORMATION OF HIGHER EDUCATION INSTITUTION Name of higher education Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences in Split institution Address Poljička cesta 35, 21000 Split, Croatia Phone Dean's Office: (021) 384 144 Fax (021) 329 288 E.mail [email protected] Internet address www.ffst.unist.hr GENERAL INFORMATION OF THE STUDY PROGRAMME Name of the study Undergraduate university study programme Philosophy (double- programme major) Provider of the study Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences programme Other participants Type of study programme Vocational study programme☐ University study programmeX UndergraduateX Graduate☐ Integrated☐ Level of study programme Postgraduate☐ Postgraduate specialist☐ Graduate specialist☐ Academic/vocational title Bachelor (baccalaureus/baccalaurea) of Arts (BA) in Philosophy earned at completion of study (univ.bacc.phil.) Undergraduate study programme Philosophy (double major) 2 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1. Reasons for starting the study programme The idea of organizing Philosophy studies has been present ever since the foundation of the Department of Humanities in Split. The development of the Humanities and Social Studies was unthinkable without philosophy and the foundation of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences in Split became meaningful upon establishing Philosophy studies. The study of philosophy is further justified by the fact that, apart from Split, the most southern city providing the opportunity of studying philosophy is Zadar which is at the very north of the Middle Dalmatia. -

European Latin Drama of the Early Modern Period in Spain, Portugal and Latin America

1 European Latin Drama of the Early Modern Period in Spain, Portugal and Latin America Joaquín Pascual Barea Introduction In the Hispanic Neo-Latin theatre, ancient drama converged with cultured and popular medieval genres such as elegiac comedy, debates and religious performances, as well as humanistic comedy from Italy and from the Low Countries, and other dramatic, poetic and oratorical genres from the Modern Age. Before a historical survey, we also analyze the influence of Aristotle’s and Horace’s poetics and of ancient drama on Neo-Latin drama, paying particular attention to the structure, the number of acts, the characters, the use of prose or verse, and the main dramatic genres. The History of Neo-Latin drama in Iberia and Latin America has been divided into four periods. During the reign of the Catholic Kings (1479–1516), the first Latin eclogues and dialogues produced in Spain, and the works of Hercules Florus and Johannes Parthenius de Tovar in the Kingdom of Aragon deserve our interest. Under the King and Emperor Charles (1516–1556), we consider the main authors of Neo-Latin drama: Joannes Angelus Gonsalves and Joannes Baptista Agnesius in Valencia, and Franciscus Satorres in Catalonia; Joannes Maldonatus in Salamanca and Burgos; Joannes Petreius at the University of Alcalá de Henares, and Franciscus Cervantes de Salazar in Mexico, as well as Didacus Tevius in Portugal under John III (1521–1557). A few months before the reign of King Sebastian in Portugal and King Philip in Spain (1556–1598), the Society of Jesus started their dramatic activity in the different provinces of Iberia: Portugal, Andalusia, Castile, Toledo and Aragon.