The Mormon Mission in the Kingdom of Sardinia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Separations-06-00017-V2.Pdf

separations Article Perfluoroalkyl Substance Assessment in Turin Metropolitan Area and Correlation with Potential Sources of Pollution According to the Water Safety Plan Risk Management Approach Rita Binetti 1,*, Paola Calza 2, Giovanni Costantino 1, Stefania Morgillo 1 and Dimitra Papagiannaki 1,* 1 Società Metropolitana Acque Torino S.p.A.—Centro Ricerche, Corso Unità d’Italia 235/3, 10127 Torino, Italy; [email protected] (G.C.); [email protected] (S.M.) 2 Università di Torino, Dipartimento di Chimica, Via Pietro Giuria 5, 10125 Torino, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondences: [email protected] (R.B.); [email protected] (D.P.); Tel.: +39-3275642411 (D.P.) Received: 14 December 2018; Accepted: 28 February 2019; Published: 19 March 2019 Abstract: Per and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) are a huge class of Contaminants of Emerging Concern, well-known to be persistent, bioaccumulative and toxic. They have been detected in different environmental matrices, in wildlife and even in humans, with drinking water being considered as the main exposure route. Therefore, the present study focused on the estimation of PFAS in the Metropolitan Area of Turin, where SMAT (Società Metropolitana Acque Torino S.p.A.) is in charge of the management of the water cycle and the development of a tool for supporting “smart” water quality monitoring programs to address emerging pollutants’ assessments using multivariate spatial and statistical analysis tools. A new “green” analytical method was developed and validated in order to determine 16 different PFAS in drinking water with a direct injection to the Ultra High Performance Liquid Chromatography tandem Mass Spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) system and without any pretreatment step. -

MARY JANE WOODGER 275 E Joseph Smith Building Brigham Young University Provo, Utah 84602 (801) 422-9029 Work

MARY JANE WOODGER 275 E Joseph Smith Building Brigham Young University Provo, Utah 84602 (801) 422-9029 Work PROFESSIONAL TRACK 2009-present Professor of Church History and Doctrine, BYU 2003-2009 Associate Professor of Church History and Doctrine, BYU 1997-2003 Assistant Professor of Church History and Doctrine, BYU 1994-99 Faculty, Department of Ancient Scripture, BYU Salt Lake Center 1980-97 Department Chair of Home Economics, Jordan School District, Midvale Middle School, Sandy, Utah EDUCATION 1997 Ed.D. Brigham Young University, Educational Leadership, Minor: Church History and Doctrine 1992 M.Ed. Utah State University, Secondary Education, Emphasis: American History 1980 B.S. Brigham Young University, Home Economics Education HONORS 2012 The Harvey B. Black and Susan Easton Black Outstanding Publication Award: Presented in recognition of an outstanding published scholarly article or academic book in Church history, doctrine or related areas for Against the Odds: The Life of George Albert Smith (Covenant Communications, Inc., 2011). 2012 Alice Louise Reynolds Women-in-Scholarship Lecture 2006 Brigham Young University Faculty Women’s Association Teaching Award 2005 Utah State Historical Society’s Best Article Award “Non Utah Historical Quarterly,” for “David O. McKay’s Progressive Educational Ideas and Practices, 1899-1922.” 1998 Kappa Omicron Nu, Alpha Tau Chapter Award of Excellence for research on David O. McKay 1997 The Crystal Communicator Award of Excellence (An International Competition honoring excellence in print media, 2,900 entries in 1997. Two hundred recipients awarded.) Research consultant for David O. McKay: Prophet and Educator Video 1994 Midvale Middle School Applied Science Teacher of the Year 1987 Jordan School District Vocational Teacher of the Year PUBLICATIONS Authored Books (18) Casey Griffiths and Mary Jane Woodger, 50 Relics of the Restoration (Springville, Utah: Cedar Fort Press, 2020). -

Strife, Despair, and a Spirit of Emigration, 1852–55

3 STRIFE, DESPAIR, AND A SPIRIT OF EMIGRATION, 1852–55 fter Lorenzo Snow’s final departure from Italy in 1852, AJabez Woodard expanded the mission outside the Walden- sian valleys. The missionaries began preaching in Turin, where they attracted the attention not only of government officials but also of Catholics and Protestants, who were dis- missive of their activities in the kingdom’s capital city. Later, the missionaries ventured to Genoa, the second largest city in the Kingdom of Sardinia. But they had little success out- side the Waldensian valleys and thereafter focused most of their energies working with the families and friends of church members. While proselytizing efforts continued to find some success among the Waldensians, most of the active mem- bers left the valleys, bound for Utah to gather with the Saints. Into the Plains of Piedmont and the Coasts of Liguria Jabez Woodard left Malta shortly after 28 June 1852, the day he organized a branch of the church there with the assistance of 81 82 MORMONS IN THE PIAZZA Elder Thomas Obray (who had arrived from England just after Snow’s departure).1 Back in the Waldensian valleys again, Wood- ard commended John Daniel Malan for his able leadership of the church during the missionaries’ absence and recommenced preaching from home to home and baptizing new converts. He also encountered recalcitrance among the Mormon converts and therefore “pruned the vineyard, cutting off dead branches,” excommunicating the dissident or unfaithful members from the church.2 In late July 1852, Woodard made his first proselytizing foray into Catholic territory, spending three weeks in Turin preaching and passing out literature. -

Relazione Finale

STUDIO INTEGRATO PER LA CONSERVAZIONE DELLE POPOLAZIONI DI SALAMANDRA LANZAI DELL’ALTA VAL GERMANASCA E DELL’ALTA VAL PO RELAZIONE CONCLUSIVA Luglio 2005 1 Studio Integrato per la Conservazione delle Popolazioni di Salamandra lanzai dell’Alta Val Germanasca e dell’Alta Val Po * Redazione a cura di Franco Andreone, Paolo Eusebio Bergò & Vincenzo Mercurio † * Questa è la relazione conclusiva del progetto di studio su Salamandra lanzai, svolto nel biennio 2003-2004. Per la realizzazione dello stesso hanno collaborato diverse persone, come segue: Franco Andreone (coordinamento scientifico, attività sul campo, elaborazione dei dati e redazione dei testi), Stefano Bovero (attività sul campo), Stefano Camanni (coordinamento amministrativo), Stefano Doglio (attività sul campo), Paolo Eusebio Bergò (attività sul campo, elaborazione dei dati, cartografia e redazione dei testi), Marco Favelli (attività sul campo, archiviazione dei dati, rilettura dei testi), Enrico Gazzaniga (attività sul campo), Vincenzo Mercurio (attività sul campo, elaborazione e redazione dei testi), Patrick Stocco (attività sul campo). Nel corso della realizzazione di questo progetto diverse persone hanno contribuito con suggerimenti, aiuto sul campo e altro. Ci teniamo particolarmente a ringraziare: Claude Miaud, Chiara Minuzzo, Carlotta Giordano, Elena Gavetti, Rafael M. Repetto, Giulia Tessa, Roberta Pala e Gianni Valente. L’Ospedale di Ivrea, Reparto di Radiologia, ci ha considerevolmente aiutati per la realizzazione delle radiografie. La Regione Piemonte e il Servizio Aree Protette, in particolare nelle persone di Ermanno de Biaggi e Marina Cerra, in quanto particolarmente sensibili alle sorti della salamandra permettendo uno studio di grande interesse conservazionistico e naturalistico. Ringraziamo infine il Parco del Po – Sezione Cuneese che ha favorito lo studio. -

Pagina 1 Comune Sede Torino Sede Grugliasco Sede Orbassano Torino

Sede Sede Sede Comune Torino Grugliasco Orbassano Torino 21388 794 461 Moncalieri 987 51 29 Collegno 958 70 41 Numero di iscritti alle Rivoli 894 79 72 sedi UNITO di Torino, Settimo Torinese 832 22 10 Grugliasco e Nichelino 752 26 27 Orbassano distinte Chieri 713 55 14 Grugliasco 683 94 32 Venaria Reale 683 26 23 Ad es. sono 958 i Pinerolo 600 19 37 domiciliati a Collegno Chivasso 445 22 3 che sono iscritti a CdS San Mauro Torinese 432 21 7 Orbassano 404 27 31 sono 70 i domiciliati a Carmagnola 393 24 5 Collegno che sono Ivrea 381 23 1 iscritti a CdS con sede Cirié 346 14 12 Caselle Torinese 323 17 12 sono 41 i domiciliati a Rivalta di Torino 307 28 29 Collegno che sono Piossasco 292 16 25 iscritti a CdS con sede Beinasco 284 16 23 Alpignano 274 24 11 Volpiano 271 12 1 Pianezza 264 18 3 Vinovo 262 11 14 Borgaro Torinese 243 16 1 Giaveno 238 12 11 Rivarolo Canavese 232 7 Leini 225 10 4 Trofarello 224 18 5 Pino Torinese 212 8 3 Avigliana 189 14 16 Bruino 173 6 16 Gassino Torinese 173 10 1 Santena 161 13 4 Druento 159 8 6 Poirino 151 12 5 San Maurizio Canavese 151 8 7 Castiglione Torinese 149 8 2 Volvera 135 5 7 None 133 7 3 Carignano 130 4 1 Almese 124 10 4 Brandizzo 120 4 1 Baldissero Torinese 119 5 1 Nole 118 5 3 Castellamonte 116 5 Cumiana 114 6 9 La Loggia 114 7 3 Cuorgné 111 5 2 Cambiano 108 9 5 Candiolo 108 7 2 Pecetto Torinese 108 6 2 Buttigliera Alta 102 9 4 Luserna San Giovanni 101 7 8 Caluso 100 1 Pagina 1 Sede Sede Sede Comune Torino Grugliasco Orbassano Bussoleno 97 6 1 Rosta 90 12 4 San Benigno Canavese 88 2 Lanzo Torinese -

Separate Prayers

VOLUME SIX, NUMBER SIX NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 1981 Publi~:ker/Editor PETER BERGER PEGGY FLETCHER CONTEMPORARY 38 THE DILEMMAS OF PLURALISM Mana,gin,~ Editor ISSUES Need we fear the religious uncertainty of modernity? SUSAN STAKER OMAN Associate Editor MORMON WOMEN AND THE STRUGGLE FOR LORIE WINDER DEFINITION Assistant Editor. An evening with the B.H. Roberts Society NICOLE HOFFMAN Ar~~ Director 7 The Nineteenth Century Church CAROL CORNWALL MADSEN WARREN ARCHER II 12 Contemporary Women LAVINA FIELDING ANDERSON Drl,arl,u’,t Editors DENNIS CLARK, POETRY 17 What is the Church? FRANCINE RUSSELL BENNION ANNE THIEME, ONE FOLD SCRIPTURAL COMMENTARY, STEVEN F. CHRISTENSEN HISTORY 44 GROWING UP IN EARLY UTAH: THE WASATCH Staff LITERARY ASSOCIATION, 1874-1878 RONALD W. WALKER KERRY WJLLIAM BATE A jaunty forerunner of the MIA LOUISE BROWN PAUL BROWN 21 ZION: THE STRUCTURE OF A THEOLOGICAL SUSAIN KEENE REVOLUTION STEVEN L. OLSEN L. JOHN LEWIS CHRIS THOMAS History of an LDS idea MARK THOMAS 55 THE MORMON PAST: REVEALED OR REVISITED? JAN SHIPPS FINETTE WALKER Circulation/Promotion Distinguishing between sacred and ordinary history REBECCAH T. HARRIS RENEE HEPWORTH MARK JARDINE RELIGION 52 FINITIST THEOLOGY AND THE PROBLEM OF Business Manager BRUCE BENNETT EVIL PETER C. APPLEBY Financial Assistants A lucid analysis of a knotty issue TOD K. CHRISTENSEN SHAWN GARCIA SCHOW 27 WHAT IS MORAL OBLIGATION WITHIN National Correspondents MORMON THEOLOGY? KIM MCCALL James W. Lucas, New York City; Searching for the source of ethical behavior George D. Smith, San Francisco; Bonnie M. Bodet and Charlotte. Johnson, Berkel~; Joel C Peterson, Dal|a$; FICTION 32 SEPARATE PRAYERS ANN EDWARDS-CANNON Anne Castleton Busath, Houston; Kris Cassity and Irene Bates, Los Ansel~$; Susan Sessions Rugh, Chicaso; Janna Daniels Haynie, Denver; POETRY 58 Sanctuary DAWN BAKER BRIMLEY Allen Palmer, Two Poems on Entanglement DALE BJORK Anne Carroll P. -

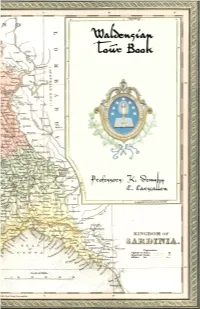

Waldensian Tour Book

1 ii LUX LUCET EN TENEBRIS The words surrounding the lighted candle symbolize Christ’s message in Matthew 5:16, “Let your light so shine before men that they may see your good works and glorify your father who is in heaven.” The dark blue background represents the night sky and the spiritual dark- ness of the world. The seven gold stars represent the seven churches mentioned in the book of Revelation and suggest the apostolic origin of the Waldensian church. One oak tree branch and one laurel tree branch are tied together with a light blue ribbon to symbolize strength, hope, and the glory of God. The laurel wreath is “The Church Triumphant.” iii Fifth Edition: Copyright © 2017 Original Content: Kathleen M. Demsky Layout Redesign:Luis Rios First Edition Copyright © 2011 Published by: School or Architecture Andrews University, Berrien Springs, MI 49104 Compiled and written: Kathleen M. Demsky Layout and Design: Kathleen Demsky & David Otieno Credits: Concepts and ideas are derived from my extensive research on this history, having been adapted for this work. Special credit goes to “The Burning Bush” (Captain R. M. Stephens) and “Guide to the Trail of Faith” (Maxine McCall). Where there are direct quotes I have given credit. Web Sources: the information on the subjects of; Fortress Fenestrelle, Arch of Augustus, Fortress of Exhilles and La Reggia Veneria Reale ( Royal Palace of the Dukes of Savoy) have been adapted from GOOGLE searches. Please note that some years the venue will change. iv WALDENSIAN TOUR GUIDE Fifth EDITION BY KATHLEEN M. DEMSKY v Castelluzzo April 1655 Massacre and Surrounding Events, elevation 4450 ft The mighty Castelluzzo, Castle of Light, stands like a sentinel in the Waldensian Valleys, a sacred monument to the faith and sacrifice of a people who were willing to pay the ultimate price for their Lord and Savior. -

Squadra G V N P Pen. I.V. P TC FAVRIA "B" 4 4 0 0 0 11 8 15:00 TC CAFASSE

FEDERAZIONE ITALIANA TENNIS RISULTATI DA CONFERMARE DA PARTE DEL COMITATO ORGANIZZATORE PIE - PROVINCIALE MASCHILE lim.4.3 - 2021 TORINO - PROVINCIALE 4.3 - Girone 1 SQUADRA CAMPI PALLE SEDE DI GIOCO TC LAGHI VALPERGA Terra rossa Babolat Team Valperga (TO) Wilson Roland Garros TC FAVRIA "B" Terra rossa VIA FRONT, Favria 10083 (TO) Clay Court TC CAFASSE Terra rossa Babolat Team Cafasse (TO) Dunlop Australian LE BETULLE Terra rossa Rivara (TO) Open BOSCONERO Erba sintetica Babolat Team Bosconero (TO) CLASSIFICA CALENDARIO RIS. PEN. squadra g v n p pen. i.v. P sabato 12 giugno 2021 TC FAVRIA "B" 4 4 0 0 0 11 8 15:00 TC CAFASSE - BOSCONERO 2 1 0 0 TC LAGHI VALPERGA 4 3 0 1 0 7 6 15:00 TC FAVRIA "B" - LE BETULLE 3 0 0 0 LE BETULLE 4 2 0 2 0 7 4 sabato 19 giugno 2021 TC CAFASSE 4 1 0 3 0 2 2 15:00 BOSCONERO - TC FAVRIA "B" 1 2 0 0 BOSCONERO 4 0 0 4 0 3 0 15:00 LE BETULLE - TC LAGHI VALPERGA 1 2 0 0 sabato 26 giugno 2021 15:00 TC LAGHI VALPERGA - TC CAFASSE 3 0 0 0 15:00 LE BETULLE - BOSCONERO 3 0 0 0 sabato 3 luglio 2021 15:00 BOSCONERO - TC LAGHI VALPERGA 1 2 0 0 15:00 TC FAVRIA "B" - TC CAFASSE 3 0 0 0 sabato 10 luglio 2021 15:00 TC LAGHI VALPERGA - TC FAVRIA "B" 0 3 0 0 15:00 TC CAFASSE - LE BETULLE 0 3 0 0 TC CAFASSE - BOSCONERO CHIURINO DENIS ALBANESE ENRICO 6-1 7-5 CATTANEO ANDREA ALFREDO TERRANDO UMBERTO 63 64 CATTANEO-VALENTINOTTI TERRANDO-BERTOLDO 6-2 1-6 5-10 TC FAVRIA "B" - LE BETULLE ANTONIELLO LUCA MASSA LUDOVICO 61 62 CASTAGNINO DAVIDE ANTONELLI AUGUSTO 63 60 ANTONIELLO-AUDO GIANOTTI MASSA-RE 63 46 10-7 BOSCONERO - TC FAVRIA "B" -

Waldensian Tour Guide

1 ii LUX LUCET EN TENEBRIS The words surrounding the lighted candle symbolize Christ’s message in Matthew 5:16, “Let your light so shine before men that they may see your good works and glorify your father who is in heaven.” The dark blue background represents the night sky and the spiritual dark- ness of the world. The seven gold stars represent the seven churches mentioned in the book of Revelation and suggest the apostolic origin of the Waldensian church. One oak tree branch and one laurel tree branch are tied together with a light blue ribbon to symbolize strength, hope, and the glory of God. The laurel wreath is “The Church Triumphant.” iii Fifth Edition: Copyright © 2017 Original Content: Kathleen M. Demsky Layout Redesign:Luis Rios First Edition Copyright © 2011 Published by: School or Architecture Andrews University, Berrien Springs, MI 49104 Compiled and written: Kathleen M. Demsky Layout and Design: Kathleen Demsky & David Otieno Credits: Concepts and ideas are derived from my extensive research on this history, having been adapted for this work. Special credit goes to “The Burning Bush” (Captain R. M. Stephens) and “Guide to the Trail of Faith” (Maxine McCall). Where there are direct quotes I have given credit. Web Sources: the information on the subjects of; Fortress Fenestrelle, Arch of Augustus, Fortress of Exhilles and La Reggia Veneria Reale ( Royal Palace of the Dukes of Savoy) have been adapted from GOOGLE searches. Please note that some years the venue will change. iv WALDENSIAN TOUR GUIDE Fifth EDITION BY KATHLEEN M. DEMSKY v Castelluzzo April 1655 Massacre and Surrounding Events, elevation 4450 ft The mighty Castelluzzo, Castle of Light, stands like a sentinel in the Waldensian Valleys, a sacred monument to the faith and sacrifice of a people who were willing to pay the ultimate price for their Lord and Savior. -

A Proposal for a Section of an LDS Church History Textbook for High School Students Containing the History of the Church from 1898 to 1951

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1966 A Proposal for a Section of an LDS Church History Textbook for High School Students Containing the History of the Church from 1898 to 1951 Arthur R. Bassett Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Bassett, Arthur R., "A Proposal for a Section of an LDS Church History Textbook for High School Students Containing the History of the Church from 1898 to 1951" (1966). Theses and Dissertations. 4509. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4509 This Selected Project is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. A PROPOSAL FOR A SECTION OF AN L.D. S. CHURCH HISTORY TEXTBOOK FOR HIGH SCHOOL STUDENTS CONTAINING THE HISTORY OF THE CHURCH FROM 1898 TO 1951 A Field Project Presented To The Department of Graduate Studies in Religious Instruction Brigham Young University Provo, Utah In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Religious Education by Arthur R. Bassett August 1966 PREFACE This field project had its beginning in an assignment given to the author in 1964. During the spring of that year he was commissioned by the seminary department of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints1 to formulate a lesson plan for use in teaching a seminary course of study entitled "Church History and Doctrine." As will be shown later, the need for textual material dealing with the history of Mormonism2 from 1877 to the present arose during the writing of that lesson outline. -

Heber C. Kimball and Family, the Nauvoo Years

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 15 Issue 4 Article 7 10-1-1975 Heber C. Kimball and Family, The Nauvoo Years Stanley B. Kimball Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Part of the Mormon Studies Commons, and the Religious Education Commons Recommended Citation Kimball, Stanley B. (1975) "Heber C. Kimball and Family, The Nauvoo Years," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 15 : Iss. 4 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol15/iss4/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Kimball: Heber C. Kimball and Family, The Nauvoo Years heber C kimball and family the nauvoo years stanley B kimball As one of the triumviritriumvirsof early mormon history heber C kimball led an adventuresome if not heroic life by the time he settled in nauvoo during may of 1839 he had been a black- smith and a potter had married and had five children two of whom had died he had lived in vermont new york ohio and missouri and had left or been driven out of homes in each state he had served fourteen years in a horse company of the new york militia had joined and left the close com- munion baptist church accepted mormonism had gone on four missions including one to england had become an apostle hadbad helped build the temple at kirtland had ded- icated the temple site at -

Trail Marker

Trail Marker PIONEERING YESTERDAY, TODAY AND TOMORROW Official Newsletter of the National Society of the Sons of Utah Pioneers™ June 2015, Volume 11, Number 6, Issue 119 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE CONTENTS Life seems to move along like the ebb and flow of President’s Message 1 ocean tides. Over the past few months, the life of National Calendar 3 the Sons of Utah Pioneers seems to have flowed National News more than it has ebbed. All of the flow has National Historical Symposium 3 benefitted the SUP. Membership Report 4 Some examples seem to substantiate this Chapter News impression. In January, the executive council, with Box Elder Chapter 5 the approval of the board, reorganized the office Brigham Young Chapter 5 staff. We brought on Heather Davis as our Office Centerville Chapter 6 Manager/Secretary. With the exception of the Cotton Mission Chapter 6 month she took off for maternity leave to bring Grove City Chapter 7 Baby Brother Brigham into this world, she has served us from 9 to 4, Monday through Thursday Jordan River Temple Chapter 7 at the office. Her service has been exemplary, and Maple Mountain Chapter 7 she has removed a great deal of the burden from Mills Chapter 8 members of the executive council and the board. Modesto Chapter 8 Morgan Chapter 9 At the same time, we hired Linda Sorensen as our Mt. Nebo Chapter 9 building manager. Linda has done an excellent job of managing the SUP headquarters. Revenues Murray Chapter 9 from building rentals the first four months of 2015 Salt Lake City Chapter 10 exceeded 2014 revenues by more than $3,000.