Chapter 11: Twentieth Century Revivals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Or Download Full Colour Catalogue May 2021

VIEW OR DOWNLOAD FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE 1986 — 2021 CELEBRATING 35 YEARS Ian Green - Elaine Sunter Managing Director Accounts, Royalties & Promotion & Promotion. ([email protected]) ([email protected]) Orders & General Enquiries To:- Tel (0)1875 814155 email - [email protected] • Website – www.greentrax.com GREENTRAX RECORDINGS LIMITED Cockenzie Business Centre Edinburgh Road, Cockenzie, East Lothian Scotland EH32 0XL tel : 01875 814155 / fax : 01875 813545 THIS IS OUR DOWNLOAD AND VIEW FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE FOR DETAILS OF AVAILABILITY AND ON WHICH FORMATS (CD AND OR DOWNLOAD/STREAMING) SEE OUR DOWNLOAD TEXT (NUMERICAL LIST) CATALOGUE (BELOW). AWARDS AND HONOURS BESTOWED ON GREENTRAX RECORDINGS AND Dr IAN GREEN Honorary Degree of Doctorate of Music from the Royal Conservatoire, Glasgow (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – The Hamish Henderson Award for Services to Traditional Music (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – Hall of Fame (Ian Green) East Lothian Business Annual Achievement Award For Good Business Practises (Greentrax Recordings) Midlothian and East Lothian Chamber of Commerce – Local Business Hero Award (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Hands Up For Trad – Landmark Award (Greentrax Recordings) Featured on Scottish Television’s ‘Artery’ Series (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Honorary Member of The Traditional Music and Song Association of Scotland and Haddington Pipe Band (Ian Green) ‘Fuzz to Folk – Trax of My Life’ – Biography of Ian Green Published by Luath Press. Music Type Groups : Traditional & Contemporary, Instrumental -

Folk Song in Cumbria: a Distinctive Regional

FOLK SONG IN CUMBRIA: A DISTINCTIVE REGIONAL REPERTOIRE? A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Susan Margaret Allan, MA (Lancaster), BEd (London) University of Lancaster, November 2016 ABSTRACT One of the lacunae of traditional music scholarship in England has been the lack of systematic study of folk song and its performance in discrete geographical areas. This thesis endeavours to address this gap in knowledge for one region through a study of Cumbrian folk song and its performance over the past two hundred years. Although primarily a social history of popular culture, with some elements of ethnography and a little musicology, it is also a participant-observer study from the personal perspective of one who has performed and collected Cumbrian folk songs for some forty years. The principal task has been to research and present the folk songs known to have been published or performed in Cumbria since circa 1900, designated as the Cumbrian Folk Song Corpus: a body of 515 songs from 1010 different sources, including manuscripts, print, recordings and broadcasts. The thesis begins with the history of the best-known Cumbrian folk song, ‘D’Ye Ken John Peel’ from its date of composition around 1830 through to the late twentieth century. From this narrative the main themes of the thesis are drawn out: the problem of defining ‘folk song’, given its eclectic nature; the role of the various collectors, mediators and performers of folk songs over the years, including myself; the range of different contexts in which the songs have been performed, and by whom; the vexed questions of ‘authenticity’ and ‘invented tradition’, and the extent to which this repertoire is a distinctive regional one. -

Rhythm Bones Player a Newsletter of the Rhythm Bones Society Volume 10, No

Rhythm Bones Player A Newsletter of the Rhythm Bones Society Volume 10, No. 3 2008 In this Issue The Chieftains Executive Director’s Column and Rhythm As Bones Fest XII approaches we are again to live and thrive in our modern world. It's a Bones faced with the glorious possibilities of a new chance too, for rhythm bone players in the central National Tradi- Bones Fest in a new location. In the thriving part of our country to experience the camaraderie tional Country metropolis of St. Louis, in the ‗Show Me‘ state of brother and sisterhood we have all come to Music Festival of Missouri, Bones Fest XII promises to be a expect of Bones Fests. Rhythm Bones great celebration of our nation's history, with But it also represents a bit of a gamble. We're Update the bones firmly in the center of attention. We betting that we can step outside the comfort zones have an opportunity like no other, to ride the where we have held bones fests in the past, into a Dennis Riedesel great Mississippi in a River Boat, and play the completely new area and environment, and you Reports on bones under the spectacular arch of St. Louis. the membership will respond with the fervor we NTCMA But this bones Fest represents more than just have come to know from Bones Fests. We're bet- another great party, with lots of bones playing ting that the rhythm bone players who live out in History of Bones opportunity, it's a chance for us bone players to Missouri, Kansas, Illinois, Oklahoma, and Ne- in the US, Part 4 relive a part of our own history, and show the braska will be as excited about our foray into their people of Missouri that rhythm bones continue (Continued on page 2) Russ Myers’ Me- morial Update Norris Frazier Bones and the Chieftains: a Musical Partnership Obituary What must surely be the most recognizable Paddy Maloney. -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

Exploring the Musical Traditions of Co. Leitrim & Co. Fermanagh

Exploring the Musical Traditions of County Leitrim & County Fermanagh In May 2020 Irish Arts Foundation launched a pioneering research programme. It centred on specific regional playing styles and influences within Irish traditional music originating from rural communities around the border counties of: Leitrim in the Republic of Ireland and Fermanagh in Northern Ireland. Themes 1. Regional identity. 2. Local musical traditions in Co. Leitrim and Fermanagh. 3. The families and individuals who kept the music alive, and their legacy today. Regional Identity In the time of the horse and cart - the ‘candle to bed’ age - each village, town and county had its own tunes and dances; a musical accent and dialect. This was due to relative rural isolation. So despite the close proximity of Co. Leitrim and Fermanagh, distinct regional identities - musical, religious and political – formed. When talking about regional identity and style there will always be generalisations; tunes do not carry passports and music has never been constrained by borders. Despite this, we will look at what can be widely termed, a Leitrim and a Fermanagh musical tradition. County Leitrim Leitrim is in the province of Connacht and part of the Border Region. Its largest town is Carrick-on-Shannon with a population of 3,134. Although one of Ireland’s smallest counties, Leitrim has a distinct musical tradition of flute and fiddle music. We will look at some of the individuals and groups who have shaped the Leitrim style of traditional music. Leitrim Flute Music “Co. Leitrim has preserved a distinct musical identity and tradition based largely on the flute. -

Irish Bands of the 60S & 70S | Sample Answer

Irish Bands of the 60s & 70s | Sample answer Ceoltóiri Cualann was an Irish group formed by Sean O’Riada in 1961. O’Riada had the idea of forming Ceoltóiri Cualann following the success of a group he had put together to perform music for the play “The Song of the Anvil” in 1960. Ceoltóiri Cualann would be a group to play Irish traditional songs with accompaniment and traditional dance tunes and slow airs. All folk music recorded before that time had been highly orchestrated and done in a classical way. Another aim of O’Riada’s was to revitalise the work of harpist and composer Turlough O’Carolan. Ceoltóiri Cualann was launched during a festival in Dublin in 1960 at an event called Recaireacht an Riadaigh and was an immediate success in Dublin. The group mainly played the music of O’Carolan, sean nós style songs and Irish traditional tunes, and O’Riada introduced the bodhrán as a percussion instrument. Ceoltóiri Cualann had ceased playing with any regularity by 1969 but reunited to record “O’Riada” and “O’Riada Sa Gaiety” that year. “O’Riada Sa Gaiety” was not released until after O’Riada’s death in 1971. The members of Ceoltóiri Cualann, some of whom went on to form “The Chieftains” in 1963 were O’Riada (harpsichord and bodhrán), Martin Fay, John Kelly (both fiddle), Paddy Moloney (uilleann pipes), Michael Turbidy (flute), Sonny Brogan, Éamon de Buitléir (both accordian), Ronnie Mc Shane (bones), Peadar Mercer (bodhrán), Seán Ó Sé (tenor voice) and Darach Ó Cathain (sean nós singer. Some examples of their tunes are “O’ Carolan’s Concerto” and “Planxty Irwin”. -

Why Do Morris Dancers Wear White? Chloe Metcalfe Pp

THE HISTORIES OF THE MORRIS IN BRITAIN Papers from a conference held at Cecil Sharp House, London, 25 - 26 March 2017, organized in partnership by Historical Dance Society with English Folk Dance and Song Society and The Morris Ring, The Morris Federation and Open Morris. Edited by Michael Heaney Why do Morris Dancers Wear White? Chloe Metcalfe pp. 315-329 English Folk Dance and Song Society & Historical Dance Society London 2018 ii English Folk Dance and Song Society Cecil Sharp House 2 Regent's Park Road London NW1 7AY Historical Dance Society 3 & 5 King Street Brighouse West Yorkshire HD6 1NX Copyright © 2018 the contributors and the publishers ISBN 978-0-85418-218-3 (EFDSS) ISBN 978-0-9540988-3-4 (HDS) Website for this book: www.vwml.org/hom Cover picture: Smith, W.A., ca. 1908. The Ilmington morris dancers [photograph]. Photograph collection, acc. 465. London: Vaughan Wil- liams Memorial Library. iii Contents Introduction 1 The History of History John Forrest How to Read The History of Morris Dancing 7 Morris at Court Anne Daye Morris and Masque at the Jacobean Court 19 Jennifer Thorp Rank Outsider or Outsider of Rank: Mr Isaac’s Dance ‘The Morris’ 33 The Morris Dark Ages Jameson Wooders ‘Time to Ring some Changes’: Bell Ringing and the Decline of 47 Morris Dancing in the Earlier Eighteenth Century Michael Heaney Morris Dancers in the Political and Civic Process 73 Peter Bearon Coconut Dances in Lancashire, Mallorca, Provence and on the 87 Nineteenth-century Stage iv The Early Revival Katie Palmer Heathman ‘I Ring for the General -

Playing Music for Morris Dancing

Playing Music for Morris Dancing Jeff Bigler Last updated: June 28, 2009 This document was featured in the December 2008 issue of the American Morris Newsletter. Copyright c 2008–2009 Jeff Bigler. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.3 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. This document may be downloaded via the internet from the address: http://www.jeffbigler.org/morris-music.pdf Contents Morris Music: A Brief History 1 Stepping into the Role of Morris Musician 2 Instruments 2 Percussion....................................... 3 What the Dancers Need 4 How the Dancers Respond 4 Tempo 5 StayingWiththeDancers .............................. 6 CuesthatAffectTempo ............................... 7 WhentheDancersareRushing . .. .. 7 WhentheDancersareDragging. 8 Transitions 9 Sticking 10 Style 10 Border......................................... 10 Cotswold ....................................... 11 Capers......................................... 11 Accents ........................................ 12 Modifying Tunes 12 Simplifications 13 Practices 14 Performances 15 Etiquette 16 Conclusions 17 Acknowledgements 17 Playing Music for Morris Dancing Jeff Bigler Morris Music: A Brief History Morris dancing is a form of English street performance folk dance. Morris dancing is always (or almost always) performed with live music. This means that musicians are an essential part of any morris team. If you are reading this document, it is probably because you are a musician (or potential musician) for a morris dance team. Good morris musicians are not always easy to find. In the words of Jinky Wells (1868– 1953), the great Bampton dancer and fiddler: . [My grandfather, George Wells] never had no trouble to get the dancers but the trouble was sixty, seventy years ago to get the piper or the fiddler—the musician. -

SANDY DENNY UNDER REVIEW: an Independent Critical Analysis, Limited Collectors Edition

SANDY DENNY UNDER REVIEW: An Independent Critical Analysis, Limited Collectors Edition The difference between a critical analysis of {$Sandy Denny} or {$The Velvet Underground} and {$The Rolling Stones} is that with a lot less information available on this extraordinary singer the audience is more limited. The good news is that this edition of the "Under Review" series actually lives up to the documentary status it claims, and does, indeed, hold one's attention and inform better than the {^Green Day: Under Review 1995-2000 The Middle Years}, which is basically a bunch of critics blowing lots of hot air. It seems with these "DVD/Fanzine" type commentaries that the lesser known the subject matter, the better the critique. Denny is a singer that deserves so much more acclaim and study, and this is an excellent starting point, as is the {$Kate Bush} "Under Review", and even the {$David Bowie} {^Under Review 1976-79 Berlin} analysis which concentrates on his dark but fun period. {$Fairport Convention} fiddler {$Dave Swarbrick}, journeyman {$Martin Carthy}, {$Cat Stevens} drummer {$Gerry Conway} of Denny's band, {$Fotheringay} and {$Pentangle}'s {$John Renbourn} contribute as does {$Fairport Convention} biographer {$Patrick Humphries}. That's the extra effort missing in some of these packages which makes this close to two hour presentation all the more interesting. Perhaps more important than the very decent {$Kate Bush} analysis by the {^Under Review} team, there's a "Limited Collector's Edition" with a cardboard slipcover. It's a very classy presentation and a very important history that deserves shelf space in any good library. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses English Folk under the Red Flag: The Impact of Alan Bush's `Workers' Music' on 20th Century Britain's Left-Wing Music Scene ROBINSON, ALICE,MERIEL How to cite: ROBINSON, ALICE,MERIEL (2021) English Folk under the Red Flag: The Impact of Alan Bush's `Workers' Music' on 20th Century Britain's Left-Wing Music Scene , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/13924/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 English Folk under the Red Flag: The Impact of Alan Bush’s ‘Workers’ Music’ on 20 th Century Britain’s Left-Wing Music Scene Alice Robinson Abstract Workers’ music: songs to fight injustice, inequality and establish the rights of the working classes. This was a new, radical genre of music which communist composer, Alan Bush, envisioned in 1930s Britain. -

14302 76969 1 1>

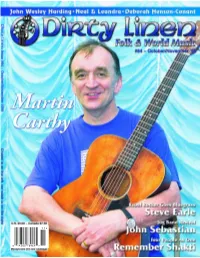

11> 0514302 76969 establishment,” he hastened to clarify. “I wish it were called the Legion of Honour, but it’s not.” Still in all, he thinks it’s good for govern- M artin C arthy ments to give cultural awards and is suitably honored by this one, which has previously gone to such outstanding folk performers as Jeannie Robertson. To decline under such circum- stances, he said, would have been “snotty.” Don’t More importantly, he conceives of his MBE as recognition he shares with the whole Call Me folk scene. “I’ve been put at the front of a very, very long queue of people who work hard to make a folk revival and a folk scene,” he said. Sir! “All those people who organized clubs for nothing and paid you out of their own pocket, and fed you and put you on the train the next morning, and put you to bed when you were drunk! What [the government is] doing, is taking notice of the fact that something’s going on for the last more than 40 years. It’s called the folk revival. They’ve ignored it for that long. And someone has suddenly taken notice, and that’s okay. A bit of profile isn’t gonna hurt us — and I say us, the plural, for the folk scene — isn’t gonna hurt us at all.” In the same year as Carthy’s moment of recognition, something happened that did hurt the folk scene. Lal Waterson, Carthy’s sister-in- law, bandmate, near neighbor and close friend, died of cancer. -

Melodic Identity and Tune Resemblance Karen E. Mcaulay

1 ABSTRACTS (grouped by session) Session 1: Melodic Identity and Tune Resemblance Karen E. McAulay (Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, Glasgow) ‘All the right notes, but not necessarily in the right order’*: Musical Resemblances over the Border The appealing Northumbrian pipe-tune, “I saw my love come passing by me”, appears in at least three nineteenth century sources, and again in Cock’s Tutor for the Northumbrian Half-Long Bagpipes. The latest two of these are shorter, whilst the first two elaborate the tune with variations. Nonetheless, the resemblances are clear; their kinship is indisputable. However, there are two much earlier appearances of similar tunes in publications north of the border. A century older, each has a different title, and although the shapes of these tunes are undeniably similar, they are certainly neither identical forerunners to one another, nor to “I saw my love”. Indeed, one source was linked in 1925 to a totally different tune. Notwithstanding this earlier identification, I dispute the similarity, and propose that there is some kind of link between “I saw my love” and her earlier Scottish cousins. Whilst the Tune Archive enabled me to trace the iterations of the Border tunes, it failed to flag up these Scottish tunes as potential relatives, partly because their rhythmic notation means the Theme Code index failed to pick up the same strong beats. I propose to demonstrate the methodology I have adopted to attempt to prove my hypothesis. If I’m right, it suggests that before I saw my love come passing by me, she had enjoyed a bit of a shadowy Celtic past.