The Waxing and Waning of Susanna Moodie's "Enthusiasm"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moodie-Strickland-Vickers Family Fonds 2Nd Acc. 1992-13 10 Cm

Moodie-Strickland-Vickers family fonds 2nd acc. 1992-13 10 cm. Finding aid Prepared by Linda Hoad August 1992 Box 1 Correspondence 1. Bartlett, Dr. [John S.] Susanna Moodie 1835 Jan. 29 2. Bartlett, Dr. [John S.] J.W.D. Moodie 1835 April 6 3. Bartlett, Dr. [John S.] Susanna Moodie 1847 Nov. 25 4. Bird, James, 1788-1839 J.W.D. Moodie 1832 June 14 5. Bird, James, 1788-1839 J.W.D. Moodie 1834 Feb. 25 [incomplete] 6. Bird, James, 1788-1839 J.W.D. Moodie 1835 May 17 [incomplete] 7. Goldschm[idt], D.L. Mrs. Mason 1885 Dec. 19 re: her daughter Sarah, his servant 8. McColl, Evan J.W.D. Moodie 1869 15 April 9. McLachlan, Alexander, Susanna Moodie 1861 Aug. 26 1818-1896 10. McLachlan, Alexander, J.W.D. Moodie 1866 9 Dec. 1818-1896 11. Moodie, Donald J.W.D. Moodie 1830 July 10 12. Moodie, J.W.D. Susanna Moodie 1839 5th July 12a. Moodie, Susanna Ethel Vickers 1882 4 March [removed from the back of watercolour of moths to which the letter refers] 13. Pringle, Thomas, S. Strickland 1829 Jan. 17 1789-1834 14. Pringle, Thomas, S. Strickland 1829 March 6 1789-1834 Manuscripts Moodie, J.W.D. Lectures by J.W. D. Moodie: "Water and its distribution over the surface of the Earth," n.d., 14 leaves "The Norsemen and their conquests and adventures," n.d., 11 leaves Box 2 Moodie, J.W.D. Music album. [ca 1840?] Some tunes copied, some original compositions. Several tunes dated: 1840, 1842. Box 3 Moodie, J.W.D. -

Italian-Canadian Female Voices: Nostalgia and Split Identity

International Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 2, No. 5; November 2015 Italian-Canadian Female Voices: Nostalgia and Split Identity Carla Comellini Associate Professor English Literature, Director of the Canadian Centre "Alfredo Rizzardi" University of Bologna Via Cartoleria 5, Bologna Notwithstanding the linguistic and cultural differences between the English and French areas, Canadian Literature can be defined as a whole. This shared umbrella, called Canada, creates an image of mutual correspondence that can be metaphorically expressed in culinary terms if one likes to use the definition ironically adopted by J.K. Keefer: “the roast beef of old England and the champagne of la douce Franc,” (“The East is Read”, p.141) This Canadian umbrella is also made up of other linguistic and cultural varieties: from those of the First Nation People to those imported by the immigrants. It is because of the mutual correspondence that Canadian literature is imbued with the constant metaphorical interplay between ‘nature’ and the ‘story teller’, between the individual story and the collective history, between the personal memory and the collective one. Among the immigrants, there are some Italian poets and writers who had immigrated to Canada becoming naturalized Canadians. Without mentioning all the immigrants/writers, it is worth remembering Michael Ondaatje, who was born in Sri Lanka. It is not so out of place that Ondaatje uses an Italian immigrant, David Caravaggio, as a character for both novels: In the Skin of a Lion (1988) and The English Patient (1992). David Caravaggio represents the image of the split personality of any immigrant as his name brilliantly explains: Ondaatje’s Italian Canadian character is no more Davide (the Italian Christian Name) because it had been anglicized in David. -

Susanna Moodie and the English Sketch

SUSANNA MOODIE AND THE ENGLISH SKETCH Carl Ballstadt S,USANNA MOODIE's Roughing It in the Bush has long been recognized as a significant and valuable account of pioneer life in Upper Canada in the mid-nineteenth century. From among a host of journals, diaries, and travelogues, it is surely safe to say, her book is the one most often quoted when the historian, literary or social, needs commentary on backwoods people, frontier living conditions, or the difficulty of adjustment experienced by such upper middle-class immigrants as Mrs. Moodie and her husband. The reasons for the pre-eminence of Roughing It in the Bush have also long been recognized. Mrs. Moodie's lively and humorous style, the vividness and dramatic quality of her characterization, the strength and good humour of her own personality as she encountered people and events have contributed to make her book a very readable one. For these reasons it enjoys a prominent position in any survey of our literary history, and, indeed, it has become a "touchstone" of our literary development. W. H. Magee, for example, uses Roughing It in the Bush as the prototype of local colour fiction against which to measure the degree of success of later Canadian local colourists.1 More recently, Carl F. Klinck ob- serves that Mrs. Moodie's book represents a significant advance in the develop- ment of our literature from "statistical accounts and running narratives" toward novels and romances of pioneer experience.2 Professor Klinck, in noting the fictive aspects of Mrs. Moodie's writing, sees it as part of an inevitable, indigenous de- velopment of Canadian writing, even though, in Mrs. -

The Journals of Susanna Moodie1

History of Intellectual Culture www.ucalgary.ca/hic/ · ISSN 1492-7810 2001 Haunted: The Journals of Susanna Moodie1 Jennifer Aldred Abstract Using an interpretive, hermeneutical approach, this article explores the work of Susanna Moodie, Margaret Atwood, and Charles Pachter. The intertextual resonances that connect these works are examined, as well as the link between text, image, and visuality. Susanna Moodie was a nineteenth century British immigrant to the backwoods of Canada, and her autobiographical text provides a narrative context from which both Margaret Atwood and Charles Pachter respectively grapple with and negotiate the complex, polyglossic nature of Canadian culture, identity, and art. The interface between Atwood’s poetic explication of cultural, linguistic, and literary identity and Pachter’s illustrative visual representations reveals the powerful synergy that is born when text and image collide. We are all immigrants to this place even if we were born here: the country is too big for anyone to inhabit completely, and in the parts unknown to us we move in fear, exiles and invaders. This country is something that must be chosen—it is so easy to leave—and if we do choose it we are still choosing a violent duality. Atwood, The Journals of Susanna Moodie Despite my intentions of discussing Charles Pachter’s visual rendition of Margaret Atwood’s The Journals of Susanna Moodie (1970), I found it impossible to extricate this marriage of interpretive artwork and poetry from its long lineage of intertexts. I was reminded, yet again, that as readers, viewers, and interpreters, we loop and spiral our way towards what we think is the coherent, textured “ending”—the “fi nal word” in an ancestry of narratives—only to fi nd that intertextuality has indeed unsettled discursive chronology, and middles and endings have blurred into polyglossic beginnings. -

Primary Sources

Archived Content This archived Web content remains online for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It will not be altered or updated. Web content that is archived on the Internet is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats of this content on the Contact Us page. Roughing It in the Backwoods Student Handout Susanna Moodie and Catharine Parr Traill are two of Canada’s most important 19th-century writers. Born in England, the two sisters became professional writers before they were married. In 1832, they emigrated with their Scottish husbands to Canada and settled in the backwoods of what is now Ontario, near present-day Lakefield. Their experiences as pioneers gave them much to write about, which they did in their books, articles, poems and letters to family members. This activity will give you the chance to view primary source materials online and learn about aspects of life as an early settler in the backwoods of Upper Canada. Introduction: Primary Sources A primary source is a first-hand account, by someone who participated in or witnessed an event. These sources could be: letters, books written by witnesses, diaries and journals, reports, government documents, photographs, art, maps, video footage, sound recordings, oral histories, clothing, tools, weapons, buildings and other clues in the surroundings. A secondary source is a representation of an event. It is someone's interpretation of information found in primary sources. These sources include books and textbooks, and are the best place to begin research. -

A Walking Tour of Historic Lakefield

Christ Church Community Museum presents A Walking Tour of Historic Lakefield See the original buildings that formed the downtown business core. Trace the owners’ steps to their homes on quiet streets. Find where they worshipped. Find the railway station, the steamship dock, the post offices, the sites of the first newspaper shop and the canoe companies. Just follow the map. The homes listed here are all private residences and are not open to the public. Christ Church Community Museum (1) Railway Station (9) Built in 1853-54, this old stone church and its cemetery, on the Built in 1881 and enlarged in 1902, this is the third and only banks of the Otonabee river, filled the need for a place to station to remain standing. At the peak of the era there were as worship. Samuel Strickland was instrumental in raising the funds many as four trains a day arriving and leaving, carrying mail, to build it. A stroll through the cemetery reveals the names of freight and passengers. many of the early settlers, including Strickland. Today, Christ Church is still an active church, as well as seasonal museum; it Pavilion in Isobel Morris Park (10) houses an impressive display of materials relating to the writings This heritage building was once the depot of passengers and of Susanna Moodie and Catharine Parr Traill, Margaret freight passing between the railway and the steamboats during Laurence, and Isabella Valancy Crawford. the busy summer tourist season. It was originally located beside the current marina. St. John the Baptist Church (2) Built in 1865-66, its architect was Samuel Strickland’s son, Lakefield College School (11) Walter. -

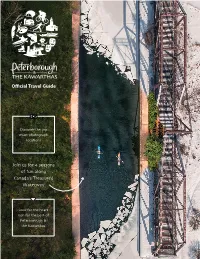

Official Travel Guide

Official Travel Guide Discover the top must-photograph locations Join us for 4 seasons of fun along Canada’s Treasured Waterway Look for the heart icon for the best-of Peterborough & the Kawarthas DISCOVER NATURE 1 An Ode to Peterborough & the Kawarthas Do you remember that We come here to recharge and refocus – to share a meal made of simple, moment? Where time farm-fresh ingredients with friends stood still? Where life (old & new) – to get away until we’ve just seemed so clear. found ourselves again. So natural. So simple? We grow here. Remaining as drawn to this place as ever, as it evolves and Life is made up of these seemingly changes, yet remains as brilliant in our small moments and the places where recollections as it does in our current memories are made. realities. We love this extraordinary place that roots us in simple moments We were children here. We splashed and real connections that will bring carefree dockside by day, with sunshine us back to this place throughout the and ice cream all over our faces. By “ It’s interesting to view the seasons seasons of our life. night, we stared up from the warmth as they impact and change the of a campfire at a wide starry sky We continue to be in awe here. region throughout the year. fascinated by its bright and To expect the unexpected. To push The difference between summer wondrous beauty. the limits on seemingly limitless and winter affects not only the opportunities. A place with rugged landscape, but also how we interact We were young and idealistic here. -

Reading Canadian Literature in a Light-Polluted Age

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 12-16-2013 12:00 AM After Dark: Reading Canadian Literature in a Light-Polluted Age David S. Hickey The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. D.M.R. Bentley The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in English A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © David S. Hickey 2013 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Hickey, David S., "After Dark: Reading Canadian Literature in a Light-Polluted Age" (2013). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 1805. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/1805 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. After Dark: Reading Canadian Literature in a Light-Polluted Age Monograph by David Hickey Graduate Program in English A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Hickey 2013 i Abstract A threat to nocturnal ecosystems and human health alike, light pollution is an unnecessary problem that comes at an enormous cost. The International Dark-Sky Association has recently estimated that the energy expended on light scatter alone is responsible for no less than twelve million tons of carbon dioxide and costs municipal governments at least $1 billion annually (“Economic Issues” 2). -

Life in the Clearings Versus the Bush

Life in the Clearings versus the Bush Susanna Moodie Life in the Clearings versus the Bush Table of Contents Life in the Clearings versus the Bush......................................................................................................................1 Susanna Moodie.............................................................................................................................................1 Introduction....................................................................................................................................................1 One. Belleville...............................................................................................................................................5 Two. Local ImprovementsSketches of Society.........................................................................................20 Three. Free SchoolsThoughts on Education.............................................................................................34 Four. Amusements.......................................................................................................................................39 Five. Trials of a Travelling Musician...........................................................................................................46 Six. The Singing Master Trials of a Travelling Musician........................................................................52 Seven. Camp Meetings................................................................................................................................64 -

Io9 Books in Review Happy That He Cannot Come

Io9 Books in Review happy that he cannot come again among them. - Some think that the Gover- nor appointed him to the office to get rid of him ... (5 October I829. Public Archives of Nova Scotia, MG I VO1. 980 reel 2) It remains the task of the critic to explain the discrepancy between this portrait of Haliburton, Canada's first international best-selling author, and the serious portrait which emerges from the letters. RUTH PANOFSKY (Ruth Panofsky is a graduate student in Canadian literature at York University where she is working on a bibliographicalstudy of Thornas Chandler Haliburton's The Clockmaker series.) Susanna Moodie. Roughing It in the Bush; or, Life in Canada. Edited by Carl Ballstadt. The Centre for Editing Early Canadian Texts. Ottawa: Carleton University Press, 1988. Ix, [8], 3-680 pp.; $24-95 (cloth), $I2.95 (paper). ISBN O-88629-043-o (cloth), IsBN 0-88629-045-7 (paper). We have been waiting for this book for a long time. Although Roughing It in the Bush is one of the most important texts written from nineteenth-century Canada, thie complications of trans-Atlantic publication and editorial intervention have until now impeded its appearance as it was originally conceived in 1852. The ver- sions upon which Moodie has been judged (often harshly) by her modern critics have derived from the revised 187I edition, which omitted most of Moodie's poems and the contributions of other members of her family: her husband's poems and chapters - 'The Village Hotel,' 'The Land-Jobber' and 'Canadian Sktetches' -which supply the family -

The Development of Narrative in the Writing of Isabella Valancy Crawford

THE DEVELOPMENT OF NARRATIVE IN THE WRITING OF ISABELLA VALANCY CRAWFORD Margo Dunn B. A. , Marianopolis College (de 11universit6de ~ontrgal), 1964 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of English @ MARGO DUNN 1975 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY April 1975 All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis or dissertation (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. The kvelopmt of Nmratim ih the !Wng of Isabella Author : (si&ature) Margo Dunn (name ) #~LYA/28 / f 7f (date) Approval Name : Margo Dunn Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis : "The kvelopnt of Narrative in the Wxitinq of Isa??llaValancy Crawford" Examining Committee : Chairman : Jared R. Curtis David Stouck 'Senior Supervisor Andrea Lebowitz Dawn Aspinall Instructor Department of English University of British Columbia Date Approved: && 25, /975 / f ABSTRACT Narrative, in its original sense, orders the world vision of an individual. -

Generic and Discursive Patterns in Catharine Parr Traill's The

GATHERING UP THE THREADS: GENERIC AND DISCURSIVE PATTERNS IN CATHARINE PARR TRAILL'S THE BACKWOODS OF CANADA by Suzanne James B .A., University of British Columbia, 1980 M.A., University of British Columbia, 1987 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of English O Suzanne James 2003 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY August 2003 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL NAME: Suzanne James DEGREE: Doctor of Philosophy (English) TITLE OF THESIS: Gathering up the Threads: Generic and Discursive Patterns in Catharine Parr Traillls "The Backwoods of Canada" Examining Committee: Chair: David Stouck Professor . Carole Gerson Professor 'hzgaret I5inley Assistant Professor Mason Harris Associate Professor ~ackl~ittk Professor, History Intern+l/External Examimq Michael Peterman Professor, English Trent University External Examiner PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission.