The Development of Narrative in the Writing of Isabella Valancy Crawford

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moodie-Strickland-Vickers Family Fonds 2Nd Acc. 1992-13 10 Cm

Moodie-Strickland-Vickers family fonds 2nd acc. 1992-13 10 cm. Finding aid Prepared by Linda Hoad August 1992 Box 1 Correspondence 1. Bartlett, Dr. [John S.] Susanna Moodie 1835 Jan. 29 2. Bartlett, Dr. [John S.] J.W.D. Moodie 1835 April 6 3. Bartlett, Dr. [John S.] Susanna Moodie 1847 Nov. 25 4. Bird, James, 1788-1839 J.W.D. Moodie 1832 June 14 5. Bird, James, 1788-1839 J.W.D. Moodie 1834 Feb. 25 [incomplete] 6. Bird, James, 1788-1839 J.W.D. Moodie 1835 May 17 [incomplete] 7. Goldschm[idt], D.L. Mrs. Mason 1885 Dec. 19 re: her daughter Sarah, his servant 8. McColl, Evan J.W.D. Moodie 1869 15 April 9. McLachlan, Alexander, Susanna Moodie 1861 Aug. 26 1818-1896 10. McLachlan, Alexander, J.W.D. Moodie 1866 9 Dec. 1818-1896 11. Moodie, Donald J.W.D. Moodie 1830 July 10 12. Moodie, J.W.D. Susanna Moodie 1839 5th July 12a. Moodie, Susanna Ethel Vickers 1882 4 March [removed from the back of watercolour of moths to which the letter refers] 13. Pringle, Thomas, S. Strickland 1829 Jan. 17 1789-1834 14. Pringle, Thomas, S. Strickland 1829 March 6 1789-1834 Manuscripts Moodie, J.W.D. Lectures by J.W. D. Moodie: "Water and its distribution over the surface of the Earth," n.d., 14 leaves "The Norsemen and their conquests and adventures," n.d., 11 leaves Box 2 Moodie, J.W.D. Music album. [ca 1840?] Some tunes copied, some original compositions. Several tunes dated: 1840, 1842. Box 3 Moodie, J.W.D. -

Download Download

Too Much Liberty in the Garrison? Closed and Open Spaces in the Canadian Sonnet Timo Müller orthrop Frye’s claim that Canadians developed “a garrison mentality” in the face of a “huge, unthinking, menacing, and formidable” landscape arguably remains the best-known state- Nment on Canadian literature, and one of the most controversial. Since its publication in Frye’s Conclusion to the Literary History of Canada (1965), it has been criticized as mythicizing, homogenizing, and cen- tering on white English Protestant writers (Lecker 284). In recent years the debate has shifted from political critique to historical contextual- ization, foregrounding issues of space, the environment, and Canadian national identity. In a 2009 collection on Frye’s work, Branko Gorjup points to the tension between the environmental determinism of the garrison mentality model and the notion of literature as “autonomous and self-generating” in Frye’s Anatomy of Criticism — a tension he finds replicated in scholarly responses (9; cf. Stacey 84). Adam Carter arrives at a similar conclusion in The Oxford Handbook of Canadian Literature (2016), where he reads Frye’s work against the contemporary debate on Canadian national identity. While Frye often dismissed the idea that the natural or cultural environment had an impact on the literature of a country, Carter notes, his concept of the garrison mentality presup- poses such an impact, as do other important essays Frye published on Canadian poetry (53-55). The analogies Frye draws between literary and spatial formations, and consequently between literary and national environments, derive from his observations both about Canadian literature and about genre traditions that reach beyond Canadian national boundaries. -

Duncan Campbell Scott - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Duncan Campbell Scott - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Duncan Campbell Scott(2 August 1862 – 19 December 1947) Duncan Campbell Scott was a Canadian poet and prose writer. With <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/charles-g-d-roberts/">Charles G.D. Roberts</a>, <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/bliss-carman/">Bliss Carman</a> and <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/archibald- lampman/">Archibald Lampman</a>, he is classed as one of Canada's Confederation Poets. Scott was also a Canadian lifetime civil servant who served as deputy superintendent of the Department of Indian Affairs from 1913 to 1932, and is "best known" today for "advocating the assimilation of Canada’s First Nations peoples" in that capacity. <b>Life</b> Scott was born in Ottawa, Ontario, the son of Rev. William Scott and Janet MacCallum. He was educated at Stanstead Wesleyan Academy. Early in life, he became an accomplished pianist. Scott wanted to be a doctor, but family finances were precarious, so in 1879 he joined the federal civil service. As the story goes, "William Scott might not have money [but] he had connections in high places. Among his acquaintances was the prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, who agreed to meet with Duncan. As chance would have it, when Duncan arrived for his interview, the prime minister had a memo on his desk from the Indian Branch of the Department of the Interior asking for a temporary copying clerk. Making a quick decision while the serious young applicant waited in front of him, Macdonald wrote across the request: 'Approved. -

Italian-Canadian Female Voices: Nostalgia and Split Identity

International Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 2, No. 5; November 2015 Italian-Canadian Female Voices: Nostalgia and Split Identity Carla Comellini Associate Professor English Literature, Director of the Canadian Centre "Alfredo Rizzardi" University of Bologna Via Cartoleria 5, Bologna Notwithstanding the linguistic and cultural differences between the English and French areas, Canadian Literature can be defined as a whole. This shared umbrella, called Canada, creates an image of mutual correspondence that can be metaphorically expressed in culinary terms if one likes to use the definition ironically adopted by J.K. Keefer: “the roast beef of old England and the champagne of la douce Franc,” (“The East is Read”, p.141) This Canadian umbrella is also made up of other linguistic and cultural varieties: from those of the First Nation People to those imported by the immigrants. It is because of the mutual correspondence that Canadian literature is imbued with the constant metaphorical interplay between ‘nature’ and the ‘story teller’, between the individual story and the collective history, between the personal memory and the collective one. Among the immigrants, there are some Italian poets and writers who had immigrated to Canada becoming naturalized Canadians. Without mentioning all the immigrants/writers, it is worth remembering Michael Ondaatje, who was born in Sri Lanka. It is not so out of place that Ondaatje uses an Italian immigrant, David Caravaggio, as a character for both novels: In the Skin of a Lion (1988) and The English Patient (1992). David Caravaggio represents the image of the split personality of any immigrant as his name brilliantly explains: Ondaatje’s Italian Canadian character is no more Davide (the Italian Christian Name) because it had been anglicized in David. -

Unit 1 English Canadian Literature

CANADIAN LITERATURE Unit 1 English Canadian Literature Unit 1 A British Immigrant in the Canadian Mosaic Page 1 Prepared by Mrs. Achamma Alex Christian College, Chengannoor Unit 1 B English Canadian Literature Page 20 Prepared by Dr. M. Snehaprabha Guruvayurappan College, Kozhikode Unit 1 C Modern Period Page 49 Prepared by Dr. H. Kalpana Pondicherry University British Immigrants in the Canadian Mosaic Majority of the immigrants who reached Canada with hopes of better living conditions and a bright future were those forced to leave their motherlands due to various reasons. While the Loyalists from the thirteen colonies of America sought to escape from the bad political situation in their country, it was poverty that prompted the Irish and the Scots to migrate to the Canadian soil. The Jews and fluverites were racially persecuted, and this paved the way for their immigration. Canada was a country of great significance to the English, French and other Europeans as they regularly fished off the banks of Newfoundland. The rivalry between England and France in Canada, in the name of colonial expansion was in fact an extension of the on-going war between the two countries on the European mainland. Their colonial rivalry ended with the division of Canada into the English-speaking territory and the French-speaking territory in 1791. The French-Canadians and the English-Canadians have been considered the "Two Founding Races" of Canada (Metcalfe 346). From the anthropological point of view, this classification is erroneous as both these groups come under the Caucasoid sub-population of human species. After the Norman Conquest of Britain in AD 1066 by William, Duke of Normandy, there had been a mixing of English and French populations. -

Susanna Moodie and the English Sketch

SUSANNA MOODIE AND THE ENGLISH SKETCH Carl Ballstadt S,USANNA MOODIE's Roughing It in the Bush has long been recognized as a significant and valuable account of pioneer life in Upper Canada in the mid-nineteenth century. From among a host of journals, diaries, and travelogues, it is surely safe to say, her book is the one most often quoted when the historian, literary or social, needs commentary on backwoods people, frontier living conditions, or the difficulty of adjustment experienced by such upper middle-class immigrants as Mrs. Moodie and her husband. The reasons for the pre-eminence of Roughing It in the Bush have also long been recognized. Mrs. Moodie's lively and humorous style, the vividness and dramatic quality of her characterization, the strength and good humour of her own personality as she encountered people and events have contributed to make her book a very readable one. For these reasons it enjoys a prominent position in any survey of our literary history, and, indeed, it has become a "touchstone" of our literary development. W. H. Magee, for example, uses Roughing It in the Bush as the prototype of local colour fiction against which to measure the degree of success of later Canadian local colourists.1 More recently, Carl F. Klinck ob- serves that Mrs. Moodie's book represents a significant advance in the develop- ment of our literature from "statistical accounts and running narratives" toward novels and romances of pioneer experience.2 Professor Klinck, in noting the fictive aspects of Mrs. Moodie's writing, sees it as part of an inevitable, indigenous de- velopment of Canadian writing, even though, in Mrs. -

ECLECTIC DETACHMENT Aspects of Identity in Canadian Poetry

ECLECTIC DETACHMENT Aspects of Identity in Canadian Poetry A. J. M. Smith I,N THE CLOSING PARAGRAPHS of the Introduction to The Oxford Book of Canadian Verse I made an effort to suggest in a phrase that I hoped might be memorable a peculiar advantage that Canadian poets, when they were successful or admirable, seemed to possess and make use of. This, of course, is a risky thing to do, for what one gains in brevity and point may very well be lost in inconclusiveness or in possibilities of misunderstanding. A thesis needs to be demonstrated as well as stated. In this particular case I think the thesis is implicit in the poems assembled in the last third of the book — and here and there in earlier places too. Nevertheless, I would like to develop more fully a point of view that exigencies of space confined me previously merely to stating. The statement itself is derived from a consideration of the characteristics of Canadian poetry in the last decade. The cosmopolitan flavor of much of the poetry of the fifties in Canada derives from the infusion into the modern world of the archetypal patterns of myth and psychology rather than (as in the past) from Christianity or nationalism. After mentioning the names of James Reaney, Anne Wilkinson, Jay Macpherson, and Margaret Avison—those of the Jewish poets Eli Mandel, Irving Layton, and Leonard Cohen might have been added—I went on to say : The themes that engage these writers are not local or even national; they are cos- mopolitan and, indeed, universal. -

The Journals of Susanna Moodie1

History of Intellectual Culture www.ucalgary.ca/hic/ · ISSN 1492-7810 2001 Haunted: The Journals of Susanna Moodie1 Jennifer Aldred Abstract Using an interpretive, hermeneutical approach, this article explores the work of Susanna Moodie, Margaret Atwood, and Charles Pachter. The intertextual resonances that connect these works are examined, as well as the link between text, image, and visuality. Susanna Moodie was a nineteenth century British immigrant to the backwoods of Canada, and her autobiographical text provides a narrative context from which both Margaret Atwood and Charles Pachter respectively grapple with and negotiate the complex, polyglossic nature of Canadian culture, identity, and art. The interface between Atwood’s poetic explication of cultural, linguistic, and literary identity and Pachter’s illustrative visual representations reveals the powerful synergy that is born when text and image collide. We are all immigrants to this place even if we were born here: the country is too big for anyone to inhabit completely, and in the parts unknown to us we move in fear, exiles and invaders. This country is something that must be chosen—it is so easy to leave—and if we do choose it we are still choosing a violent duality. Atwood, The Journals of Susanna Moodie Despite my intentions of discussing Charles Pachter’s visual rendition of Margaret Atwood’s The Journals of Susanna Moodie (1970), I found it impossible to extricate this marriage of interpretive artwork and poetry from its long lineage of intertexts. I was reminded, yet again, that as readers, viewers, and interpreters, we loop and spiral our way towards what we think is the coherent, textured “ending”—the “fi nal word” in an ancestry of narratives—only to fi nd that intertextuality has indeed unsettled discursive chronology, and middles and endings have blurred into polyglossic beginnings. -

Primary Sources

Archived Content This archived Web content remains online for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It will not be altered or updated. Web content that is archived on the Internet is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats of this content on the Contact Us page. Roughing It in the Backwoods Student Handout Susanna Moodie and Catharine Parr Traill are two of Canada’s most important 19th-century writers. Born in England, the two sisters became professional writers before they were married. In 1832, they emigrated with their Scottish husbands to Canada and settled in the backwoods of what is now Ontario, near present-day Lakefield. Their experiences as pioneers gave them much to write about, which they did in their books, articles, poems and letters to family members. This activity will give you the chance to view primary source materials online and learn about aspects of life as an early settler in the backwoods of Upper Canada. Introduction: Primary Sources A primary source is a first-hand account, by someone who participated in or witnessed an event. These sources could be: letters, books written by witnesses, diaries and journals, reports, government documents, photographs, art, maps, video footage, sound recordings, oral histories, clothing, tools, weapons, buildings and other clues in the surroundings. A secondary source is a representation of an event. It is someone's interpretation of information found in primary sources. These sources include books and textbooks, and are the best place to begin research. -

A Walking Tour of Historic Lakefield

Christ Church Community Museum presents A Walking Tour of Historic Lakefield See the original buildings that formed the downtown business core. Trace the owners’ steps to their homes on quiet streets. Find where they worshipped. Find the railway station, the steamship dock, the post offices, the sites of the first newspaper shop and the canoe companies. Just follow the map. The homes listed here are all private residences and are not open to the public. Christ Church Community Museum (1) Railway Station (9) Built in 1853-54, this old stone church and its cemetery, on the Built in 1881 and enlarged in 1902, this is the third and only banks of the Otonabee river, filled the need for a place to station to remain standing. At the peak of the era there were as worship. Samuel Strickland was instrumental in raising the funds many as four trains a day arriving and leaving, carrying mail, to build it. A stroll through the cemetery reveals the names of freight and passengers. many of the early settlers, including Strickland. Today, Christ Church is still an active church, as well as seasonal museum; it Pavilion in Isobel Morris Park (10) houses an impressive display of materials relating to the writings This heritage building was once the depot of passengers and of Susanna Moodie and Catharine Parr Traill, Margaret freight passing between the railway and the steamboats during Laurence, and Isabella Valancy Crawford. the busy summer tourist season. It was originally located beside the current marina. St. John the Baptist Church (2) Built in 1865-66, its architect was Samuel Strickland’s son, Lakefield College School (11) Walter. -

INTERDISCIPLINARY JOURNAL of DECADENCE STUDIES Issue 1 Spring 2018 Hierophants of Decadence: Bliss Carman and Arthur Symons Rita

INTERDISCIPLINARY JOURNAL OF DECADENCE STUDIES Issue 1 Spring 2018 Hierophants of Decadence: Bliss Carman and Arthur Symons Rita Dirks ISSN: 2515-0073 Date of Acceptance: 1 June 2018 Date of Publication: 21 June 2018 Citation: Rita Dirks, ‘Hierophants of Decadence: Bliss Carman and Arthur Symons’, Volupté: Interdisciplinary Journal of Decadence Studies, 1 (2018), 35-55. volupte.gold.ac.uk This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Hierophants of Decadence: Bliss Carman and Arthur Symons Rita Dirks Ambrose University Canada has never produced a major man of letters whose work gave a violent shock to the sensibilities of Puritans. There was some worry about Carman, who had certain qualities of the fin de siècle poet, but how mildly he expressed his queer longings! (E. K. Brown) Decadence came to Canada softly, almost imperceptibly, in the 1880s, when the Confederation poet Bliss Carman published his first poems and met the English chronicler and leading poet of Decadence, Arthur Symons. The event of Decadence has gone largely unnoticed in Canada; there is no equivalent to David Weir’s Decadent Culture in the United States: Art and Literature Against the American Grain (2008), as perhaps has been the fate of Decadence elsewhere. As a literary movement it has been, until a recent slew of publications on British Decadence, relegated to a transitional or threshold period. As Jason David Hall and Alex Murray write: ‘It is common practice to read [...] decadence as an interstitial moment in literary history, the initial “falling away” from high Victorian literary values and forms before the bona fide novelty of modernism asserted itself’.1 This article is, in part, an attempt to bring Canadian Decadence into focus out of its liminal state/space, and to establish Bliss Carman as the representative Canadian Decadent. -

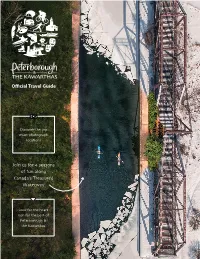

Official Travel Guide

Official Travel Guide Discover the top must-photograph locations Join us for 4 seasons of fun along Canada’s Treasured Waterway Look for the heart icon for the best-of Peterborough & the Kawarthas DISCOVER NATURE 1 An Ode to Peterborough & the Kawarthas Do you remember that We come here to recharge and refocus – to share a meal made of simple, moment? Where time farm-fresh ingredients with friends stood still? Where life (old & new) – to get away until we’ve just seemed so clear. found ourselves again. So natural. So simple? We grow here. Remaining as drawn to this place as ever, as it evolves and Life is made up of these seemingly changes, yet remains as brilliant in our small moments and the places where recollections as it does in our current memories are made. realities. We love this extraordinary place that roots us in simple moments We were children here. We splashed and real connections that will bring carefree dockside by day, with sunshine us back to this place throughout the and ice cream all over our faces. By “ It’s interesting to view the seasons seasons of our life. night, we stared up from the warmth as they impact and change the of a campfire at a wide starry sky We continue to be in awe here. region throughout the year. fascinated by its bright and To expect the unexpected. To push The difference between summer wondrous beauty. the limits on seemingly limitless and winter affects not only the opportunities. A place with rugged landscape, but also how we interact We were young and idealistic here.