The Corruption Watchdog Condemned – the Media Criticised in Letters To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Linda Scott for Sydney Strong, Local, Committed

The South Sydney Herald is available online: www.southsydneyherald.com.au FREE printed edition every month to 21,000+ regular readers. VOLUME ONE NUMBER FORTY-NINE MAR’07 CIRCULATION 21,000 ALEXANDRIA BEACONSFIELD CHIPPENDALE DARLINGTON ERSKINEVILLE KINGS CROSS NEWTOWN REDFERN SURRY HILLS WATERLOO WOOLLOOMOOLOO ZETLAND RESTORE HUMAN RIGHTS BRING DAVID HICKS HOME New South Wales decides PROTEST AT 264 PITT STREET, CITY The South Sydney Herald gives you, as a two page insert, SUNDAY MARCH 25 ✓ information you need to know about your voting electorates. PAGES 8 & 13 More on PAGE 15 Water and housing: Labor and Greens Frank hits a high note - good news for live music? go toe to toe John Wardle Bill Birtles and Trevor Davies The live music scene in NSW is set to receive a new and much fairer regu- Heffron Labor incumbent Kristina latory system, after Planning Minister Keneally has denied that the State Frank Sartor and the Iemma Govern- government’s promised desalination ment implemented amendments to plant will cause road closures and the Local Government Act including extensive roadwork in Erskineville. a streamlined process to regulate Claims that the $1.9 billion desalina- entertainment in NSW and bring us tion plant at Kurnell will cause two more into line with other states. years of roadworks across Sydney’s Passed in the last week of Parlia- southern suburbs were first made by ment in November 2006, these the Daily Telegraph in February. reforms are “long overdue, and State government plans revealed extremely good news for the live that the 9 km pipeline needed to music industry” says Planning connect the city water tunnel with the Minister Frank Sartor. -

Day 3 27 May 2021 Sydney Hosted by Macquarie University Program (Subject to Change)

Day 3 27 May 2021 Sydney Hosted by Macquarie University Program (subject to change) Session 1 (2 hours) 08:00 London; 09:00 Cairo; 10:00 Jerusalem/Beirut/Amman; 17:00 Sydney 07:00 GMT Welcome and Introductions (Dr Karin Sowada, ARC Future Fellow, Macquarie University) 07:10 GMT Social History of Cultural Interaction from Non-Elite Context: Paleoethnobotanical and Isotopic Evidence Amr Khalaf Shahat (University of California, Los Angeles) 07:30 GMT Early Dynastic and Old Kingdom Copper in Egypt: Latest Data, Open Questions Martin Odler (Charles University, Prague), Jiří Kmošek (Academy of Fine Arts, Vienna), Marek Fikrle (Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic), Yulia V. Erban Kochergina (Czech Geological Survey) 07:50 GMT ‘There’s No Place Like Home’? Travels, Travelers, and Tropes from the Old to the Middle Kingdom Anna-Latifa Mourad (Macquarie University) 08:10 GMT Tales of Destruction and Disaster: The End of Third Millennium BC in the Central and Northern Levant and its Regional Impact Melissa Kennedy (The University of Western Australia) 08:30 GMT Discussion (30 mins) Break (1 hour) 10:00 London; 11:00 Cairo; 12:00 Jerusalem/Beirut/Amman; 19:00 Sydney 1 Egypt and the Mediterranean World Day 3 27 May 2021 Sydney Program & Abstracts Session 2 (2 hours) 11:00 London; 12:00 Cairo; 13:00 Jerusalem/Beirut/Amman; 20:00 Sydney 10:00 GMT Imported Combed Ware from the Abydos Tombs of Weni the Elder and His Family Christian Knoblauch (Swansea University, Wales & University of Michigan Middle Cemetery Project) and Karin Sowada (Macquarie University) 10:20 GMT There and Back Again: A Preliminary Discussion about the Presence of Imported Artefacts in Elite Tombs of the Egyptian Early Dynastic Period Olivier P. -

Ayres and Graces Concert Program

Ayres & Graces CONTENTS PAGE Program 5 Messages 7 Biographies 11 the Australian Program notes success story that’s 22 built on energy. Get to know the future of connected energy. We’re Australia’s largest natural gas infrastructure business. With thanks We’ve been connecting Australian energy since 2000. From small beginnings we’ve become a top 50 ASX-listed company, 33 employing 1,900 people, and owning and operating one of the largest interconnected gas networks across Australia. We deliver smart, reliable and safe energy solutions through our deep industry knowledge and interconnected infrastructure.. www.apa.com.au SPECIAL EVENT Ayres & Graces DATES Sydney City Recital Hall Tuesday 27 October 7:00PM Wednesday 28 October 7:00PM Friday 30 October 7:00PM Saturday 31 October 2:00PM Saturday 31 October 7:00PM Online Digital Première Sunday 1 November 5:00PM Concert duration approximately 60 minutes with no interval. Please note concert duration is approximate only and is subject to change. We kindly request that you switch off all electronic devices prior to the performance. 2 AUSTRALIAN BRANDENBURG ORCHESTRA PHOTO CREDIT: KEITH SAUNDERS SPECIAL EVENT SPECIAL EVENT Ayres & Graces Ayres & Graces ARTISTS PROGRAM Melissa Farrow* Baroque flute & recorder Jean-Baptiste Lully Prologue: Ouverture to Cadmus et Hermione, LWV 49 Mikaela Oberg Baroque flute & recorder Marin Marais Musettes 28 and 29 from Pièces de Viole, Livre IV, Suite No. 4 Rafael Font Baroque violin in A minor Marianne Yeomans Baroque viola Anton Baba Baroque cello & viola da -

Long-Running Drama in Theatre of Public Shame

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Long-running drama in theatre of public shame MP Daryl Maguire and NSW Premier Gladys Berejiklian in Wagga in 2017. Tom Dusevic OCTOBER 16, 2020 The British have epic soap Coronation Street. Latin Americans crave their telenovelas. The people of NSW must settle for the Independent Commission Against Corruption and its popular offshoot, Keeping Up with the Spivs. The current season is one of the most absorbing: bush huckster Daz Kickback ensnares Gladys Prim in his scams. At week’s end, our heroine is tied to railroad tracks as a steaming locomotive rounds the bend. Stay tuned. In recent years the public has heard allegations of Aldi bags stuffed with cash and delivered to NSW Labor’s Sussex Street HQ by Chinese property developer Huang Xiangmo. In 2013 corruption findings were made against former Labor ministers Eddie Obeid and Ian Macdonald. The following year, Liberal premier Barry O’Farrell resigned after ICAC obtained a handwritten note that contradicted his claims he did not receive a $3000 bottle of Grange from the head of Australian Water Holdings, a company linked to the Obeids. The same year ICAC’s Operation Spicer investigated allegations NSW Liberals used associated entities to disguise donations from donors banned in the state, such as property developers. Ten MPs either went to the crossbench or quit politics. ICAC later found nine Liberal MPs acted with the intention of evading electoral funding laws, with larceny charges recommended against one. Years earlier there was the sex-for- development scandal, set around the “Table of Knowledge” at a kebab shop where developers met officials from Wollongong council. -

Images Catalogue Last Updated 15 Mar 2018

Images Catalogue Last Updated 15 Mar 2018 Record Title Date Number P8095 1st 15 Rugby Union team photo [Hawkesbury Agricultural College HAC] - WR Watkins coach 11/04/1905 P2832 3 Jersey "Matrons" held in paddock below stud stock shed for student demonstrations - Colo breed on right [Hawkesbury 30/04/1905 Agricultural College (HAC)] P8468 3 students perform an experiment at UWS Nepean Science fair for gifted & talented students - 1993 1/06/1993 P8158 3 unidentified people working at a computer in lab coats 14/06/1905 P8294 3D Illustrations at Werrington - VAPA 1/06/1992 P8292 3rd year Communications students under the "tent" - Alison Fettell (Left) & Else Lackey 27/10/1992 P8310 3rd year computer programming project 14/06/1905 P1275 4th Cavalry Mobil Veterinary Section [Hawkesbury Agricultural College (HAC)] 21/04/1905 P2275 4th Cavalry Mobile Veterinary Section [Hawkesbury Agricultural College (HAC)] 21/04/1905 P6108 5 boys playing basketball 14/05/1905 P1683 60 colour slides in a folder - these slides were reproduced in publicity brochures and booklets for Hawkesbury Agricultural 2/06/1905 College - Careers in Food Technology [Hawkesbury Agricultural College (HAC)] P6105 7 boys playing Marbles 14/05/1905 P1679 75th Anniversary of the founding of Hawkesbury Agricultural College - Unveiling the plaque (1 of 9) - B Doman (Principal) 18/03/1966 giving speech from podium [Hawkesbury Agricultural College (HAC)] P1809 75th Anniversary of the founding of Hawkesbury Agricultural College - Unveiling the plaque (2 of 9) - Three men 18/03/1966 (unidentified) [Hawkesbury Agricultural College (HAC)] P1810 75th Anniversary of the founding of Hawkesbury Agricultural College - Unveiling the plaque (3 of 9) - Speaker at podium 18/03/1966 [Hawkesbury Agricultural College (HAC)] P1811 75th Anniversary of the founding of Hawkesbury Agricultural College - Unveiling the plaque (4 of 9) - The Hon. -

Annual Report 2006–07

annual report 2006–07 CEDA Level 5, 136 Exhibition Street Melbourne 3000 Australia Telephone: (03) 9662 3544 Fax: (03) 9663 7271 Email: [email protected] Web: ceda.com.au About this publication Annual Report 2006–07 © CEDA 2007 ISSN 1832-8822 This publication is available on CEDA’s website: ceda.com.au For an emailed or printed copy, please contact the national office on 03 9662 3544 or [email protected] Design: Robyn Zwar Graphic Design Photography: Sean Davey/BRW, iStockphoto, Jason McCormack, Paul Lovelace Photography, Photonet, Yusuke Sato contents What is CEDA? ...............................................................2 Chairman’s report...........................................................4 CEO’s report...................................................................5 Review of operations......................................................6 Membership .............................................................7 Research ...............................................................12 Events.....................................................................16 International activity.................................................23 Communications ....................................................25 Governance..................................................................28 Concise financial report................................................34 Overview.................................................................35 Directors’ report ......................................................38 Income statement....................................................41 -

From Constitutional Convention to Republic Referendum: a Guide to the Processes, the Issues and the Participants ISSN 1328-7478

Department of the Parliamentary Library INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES •~J..>t~)~.J&~l<~t~& Research Paper No. 25 1998-99 From Constitutional Convention to Republic Referendum: A Guide to the Processes, the Issues and the Participants ISSN 1328-7478 © Copyright Commonwealth ofAustralia 1999 Except to the exteot of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent of the Department ofthe Parliamentary Library, other than by Senators and Members ofthe Australian Parliament in the course oftheir official duties. This paper has been prepared for general distribntion to Senators and Members ofthe Australian Parliament. While great care is taken to ensure that the paper is accurate and balanced,the paper is written using information publicly available at the time of production. The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Information and Research Services (IRS). Advice on legislation or legal policy issues contained in this paper is provided for use in parliamentary debate and for related parliamentary purposes. This paper is not professional legal opinion. Readers are reminded that the paper is not an official parliamentary or Australian govermnent document. IRS staff are available to discuss the paper's contents with Senators and Members and their staffbut not with members ofthe public. , ,. Published by the Department ofthe Parliamentary Library, 1999 INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES , Research Paper No. 25 1998-99 From Constitutional Convention to Republic Referendum: A Guide to the Processes, the Issues and the Participants Professor John Warhurst Consultant, Politics and Public Administration Group , 29 June 1999 Acknowledgments This is to acknowledge the considerable help that I was given in producing this paper. -

Political Briefings: - Barry O’Farrell MP, NSW Leader of the Opposition: Thursday 27Th May 2010

Political Briefings: - Barry O’Farrell MP, NSW Leader of the Opposition: Thursday 27th May 2010 1) Libertarian and Progressive Conservatism: Concept/Strategy as stated to Shadow Minister for Foreign Affairs, Julie Bishop MP, re Chief of Staff emails in late 2009 for then Federal Leader of Opposition, Malcolm Turnbull MP. 2) Tailored Policies/Programmes: Obviously the Federal and NSW political, economic, social and cultural circumstances are different or at least not exactly the same. Sydney’s “regionalism” has historical peculiarities as the “founding city” of the nation. Sydney always looked to the Mother Country, UK, and its colonial “off-shoots: in Tasmania, Victoria, New Zealand and Queensland, and through them to the Pacific Islands in the South West Pacific. NSW was predominantly Free Trade in persepective rather than Protectionist as in Victoria. 3) Political Parties in New South Wales: The ALP – since Sir William McKell MP, Premier 1941-47 a) McKell to Renshaw - Premiers 1941-65 b) Wran and Unsworth – Premiers 1976-88 c) Carr to Keneally – Premiers 1995-2011 The Liberal Party – since Sir Robert Askin MP, Premier 1965-75 a) Pre WW11 – Bertram Stevens 1932-39 b) The Bob Askin years - a decade of alleged “corruption”. c) Greiner and Fahey – 1988-1995 4) Barry O’Farrell – State Leader of the Opposition: a) Comment by Nick Greiner: http://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/opinion/election-is-the-only-opinion-poll-that- matters/story-e6frg6zo-1225869365983 b) The Rudd/Abbott contest for PM -2010 c) Three/four terms of ‘Good” Liberal Party Government – 2011/27 5) ACCCI Interests a) NSW is “in” the Trade Business – Ministry for Foreign Economic Relations b) Greater Sydney as a World City – one Mayor, many Deputies. -

1 Heat Treatment This Is a List of Greenhouse Gas Emitting

Heat treatment This is a list of greenhouse gas emitting companies and peak industry bodies and the firms they employ to lobby government. It is based on data from the federal and state lobbying registers.* Client Industry Lobby Company AGL Energy Oil and Gas Enhance Corporate Lobbyists registered with Enhance Lobbyist Background Limited Pty Ltd Corporate Pty Ltd* James (Jim) Peter Elder Former Labor Deputy Premier and Minister for State Development and Trade (Queensland) Kirsten Wishart - Michael Todd Former adviser to Queensland Premier Peter Beattie Mike Smith Policy adviser to the Queensland Minister for Natural Resources, Mines and Energy, LHMU industrial officer, state secretary to the NT Labor party. Nicholas James Park Former staffer to Federal Coalition MPs and Senators in the portfolios of: Energy and Resources, Land and Property Development, IT and Telecommunications, Gaming and Tourism. Samuel Sydney Doumany Former Queensland Liberal Attorney General and Minister for Justice Terence John Kempnich Former political adviser in the Queensland Labor and ACT Governments AGL Energy Oil and Gas Government Relations Lobbyists registered with Government Lobbyist Background Limited Australia advisory Pty Relations Australia advisory Pty Ltd* Ltd Damian Francis O’Connor Former assistant General Secretary within the NSW Australian Labor Party Elizabeth Waterland Ian Armstrong - Jacqueline Pace - * All lobbyists registered with individual firms do not necessarily work for all of that firm’s clients. Lobby lists are updated regularly. This -

De Vries 2000

MEDITERRANEAN ARCHAEOLOGY Vol. 13,2000 , ... OFFPRINT AUSTRALIAN AND NEW ZEALAND JOURNAL FOR THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE MEDITERRANEAN WORLD MEDITERRANEAN ARCHAEOLOGY Australian and New Zealand Journal for the Archaeology of the Mediterranean World Editor; Jean-Paul Descreudres Assistant Editor: Derek Harrison EdHorial Hoard Camilla Norman, Ted Robinson. Karin Sowada, Alan Walmsley. Gaye Wilson Advisory Hoard D. Anson (Otago Museulll. Dunedin). A. Betts (The University of Sydney). T. Bryce (Lincoln University. New Zealand). A. CambilOg!ou (The Australian Archaeological Institute at Athens), G. W. Clarke (The National University. Canberra), D. Frankel (La Trobc University. Melbourne), J. R. Green (The University of Sydney), R. Hannah (The University of Olago, Dunedin), M. Harari (University of Pavia). V. Karagcorghis (University of Cyprus). 1. V. S. Mcgaw (Flinders University. Adelaide), J. Melville-Jones (The University of Western Australia. Perth). J.-M. Morel (University or Geneva). B. Ockinga (Macquarie University, Sydney). I. Pini (University of Marburg). R. Ridley. A. Sagona. F. Sear (The University of Melbourne). M. Strong (Abbey Museum. Caboolturc). M. Wilson Jones (Rome). R. V. S. Wright (Sydney), J.-L. Zimmermann (University of Geneva). Managerial Committee D. Betls (John Elliott Classics Museum. University of Tasmania. Hobart), A. Cambitoglou (Australian Archaeological Institute 31 Athens), G. Clarke (Humanities Research Centre. The Australian National University. Canberra), R. Hannah (The University of Otago. Dunedin), C. A. Hope (Dept. of Greek, Roman. and Egyptian Studies, Monash University, Melbourne). J. Melville-Jones (Dept. of Classics and Ancient History, The University of Western Australia, Perth), A. Morfall (Department or Art History. The Australian National University. Canberra), C. E. V. Nixon (School of History, Philosophy and Politics. -

Legislative Assembly

12862 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Tuesday 16 November 2004 ______ Mr Speaker (The Hon. John Joseph Aquilina) took the chair at 2.15 p.m. Mr Speaker offered the Prayer. STATE GOVERNMENT FAMILIARISATION PROGRAM TWENTY-FIRST ANNIVERSARY Mr SPEAKER: It is with pleasure that I advise the House that today, together with my colleague the President, I welcomed to the Parliament of New South Wales participants in the twenty-first anniversary of the State Government Familiarisation Program. This program is an activity of the Parliamentary Education and Community Relations Section. The operating surplus supports parliamentary education programs, particularly for students from non-metropolitan areas. Over its 21 years 2,415 businesspeople have taken part in the program. The President and I joined in a special luncheon at which we presented certificates of appreciation to speakers and departments who have been involved since the inception of the program. MINISTRY Mr BOB CARR: I advise honourable members that during the absence of the Minister for Police, who is attending the Australian Police Ministers Council in Tasmania, I will answer questions on his behalf. PETITIONS Wagga Wagga Electorate Schools Airconditioning Petition requesting the installation of airconditioning in all learning spaces in public schools in the Wagga Wagga electorate, received from Mr Daryl Maguire. Mature Workers Program Petition requesting that the Mature Workers Program be restored, received from Ms Clover Moore. Skilled Migrant Placement Program Petition requesting that the Skilled Migrant Placement Program be restored, received from Ms Clover Moore. Gaming Machine Tax Petitions opposing the decision to increase poker machine tax, received from Mrs Judy Hopwood and Mr Andrew Tink. -

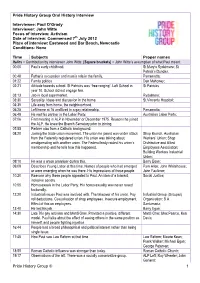

Paul O'grady Interviewer: John Witte Focus O

Pride History Group Oral History Interview Interviewee: Paul O’Grady Interviewer: John Witte Focus of interview: Activism Date of interview: Commenced 7th July 2012 Place of interview: Eastwood and Bar Beach, Newcastle Conditions: None Time Subjects Proper names Italics = Contribution by interviewer John Witte, [Square brackets] = John Witte’s assumption of what Paul meant. 00:00 Paul’s early childhood. St Mary’s Rydalmere; St Patrick’s Dundas; 00:48 Father’s occupation and mum’s role in the family. Parramatta; 01:22 Family politics. Dan Mahoney; 02:21 Attitude towards school. St Patricks was “free ranging”. Left School in St Patricks year 10. School did not engage him. 03:13 Job in local supermarket. Rydalmere; 03:30 Sexuality. Ideas and discussion in the home. St Vincents Hospital; 04:35 Life away from home, the neighbourhood. 05:25 Left home at 16 and lived in a gay relationship. Parramatta; 06:49 He met his partner in the Labor Party. Australian Labor Party; 07:06 First meeting in ALP in November or December 1975. Reasons he joined the ALP. He knew the Branch Secretary prior to joining. 07:55 Partner also from a Catholic background. 08:20 Joining the trade union movement. The union he joined was under attack Shop Branch, Australian from the Federally registered union. His union was talking about Workers’ Union; Shop amalgamating with another union. The Federal body raided his union’s Distributive and Allied membership and he tells how this happened. Employees Association; Building Workers Industrial Union; 09:10 He was a union organiser during this.