National Register of Historic Places- Multiple Property Documentation Form

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Overton Park Court Apartments View the Final National Register Nomination

United States Department of the Interior National Register Listed National Park Service 6/28/2021 National Register of Historic Places Registration Form MP100006712 This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name Overton Park Court Apartments Other names/site number Park Lane Apartments Name of related multiple property listing Historic Residential Resources of Memphis, Shelby County, TN 2. Location Street & Number: 2095 Poplar Avenue City or town: Memphis State: TN County: Shelby Not For Publication: N/A Vicinity: N/A Zip: 38104_________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property __X_ meets ___ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national statewide X local Applicable National Register Criteria: X A B X C D Signature of certifying official/Title: Date Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer, Tennessee Historical Commission State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Reference # Resource Name Address County City Listed Date Multiple

Reference # Resource Name Address County City Listed Date Multiple Name 76001760 Arnwine Cabin TN 61 Anderson Norris 19760316 92000411 Bear Creek Road Checking Station Jct. of S. Illinois Ave. and Bear Creek Rd. Anderson Oak Ridge 19920506 Oak Ridge MPS 92000410 Bethel Valley Road Checking Station Jct. of Bethel Valley and Scarboro Rds. Anderson Oak Ridge 19920506 Oak Ridge MPS 91001108 Brannon, Luther, House 151 Oak Ridge Tpk. Anderson Oak Ridge 19910905 Oak Ridge MPS 03000697 Briceville Community Church and Cemetery TN 116 Anderson Briceville 20030724 06000134 Cross Mountain Miners' Circle Circle Cemetery Ln. Anderson Briceville 20060315 10000936 Daugherty Furniture Building 307 N Main St Anderson Clinton 20101129 Rocky Top (formerly Lake 75001726 Edwards‐‐Fowler House 3.5 mi. S of Lake City on Dutch Valley Rd. Anderson 19750529 City) Rocky Top (formerly Lake 11000830 Fort Anderson on Militia Hill Vowell Mountain Rd. Anderson 20111121 City) Rocky Top (formerly Lake 04001459 Fraterville Miners' Circle Cemetery Leach Cemetery Ln. Anderson 20050105 City) 92000407 Freels Cabin Freels Bend Rd. Anderson Oak Ridge 19920506 Oak Ridge MPS Old Edgemoor Rd. between Bethel Valley Rd. and Melton Hill 91001107 Jones, J. B., House Anderson Oak Ridge 19910905 Oak Ridge MPS Lake 05001218 McAdoo, Green, School 101 School St. Anderson Clinton 20051108 Rocky Top (formerly Lake 14000446 Norris Dam State Park Rustic Cabins Historic District 125 Village Green Cir. Anderson 20140725 City) 75001727 Norris District Town of Norris on U.S. 441 Anderson Norris 19750710 Tennessee Valley Authority Hydroelectric 16000165 Norris Hydrolectric Project 300 Powerhouse Way Anderson Norris 20160412 System, 1933‐1979 MPS Roughly bounded by East Dr., W. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form 1. Name 2. Location 3. Classification 4. Owner of Property 5. L

FHR-8-300 (11-78) United States Department off the Interior Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections _____________ 1. Name historic South Parkway - Heiskell Farm Historic District and/or common Same 2. Location street & number s.otftfr Parkway East and Eas-fe- Parkway N/A_ not for publication city, town Memphis N/A_ vicinity of state Tennessee code 047 county Shelby code 157 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use X district public X occupied agriculture museum building(s) X private unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational X private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object |^j / A in process X yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name Multiple Ownership street & number N/A city, town N/A N/A_ vicinity of state N/A 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Office of the Shelby County Register street & number 160 N. Main city, town Memphis state Tennessee 38103 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title N/A has this property been determined elegible? yes no date N/A N/A federal state county local depository for survey records N/A city, town state N/A 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated unaltered _X _ original site J( _ good ruins X altered moved date fair unexposed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance The South Parkway-Heiskell Farm Historic District is a self-contained three-block segment of the Memphis Parkway System located between Airways Boulevard and Lamar Avenue in the southern portion of the residential Midtown area of Memphis, Tennessee (pop. -

Bibliography 604 Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY 604 BIBLIOGRAPHY ARTICLES Appalachian Journal 1928 Greeneville Becomes...Great Tourist Center. September:2. 1932 Indian Gap Highway. April:1. Bailey, Thomas E. 1969 Engine and Iron: A Story of Branchline Railroading in Middle Tennessee. Tennessee Historical Quarterly. 28:252-268. Boniol, John Dawson Jr. 1971 The Walton Road. Tennessee Historical Quarterly. 30:402-412. Bridges, Lamar W. 1973 Tennessee Representative Kenneth McKellar and the Sixty-Second Congress (1922-1913). The West Tennessee Historical Society Papers. 27:63-80. Case, M. B. 1915 New Mississippi River Bridge at Memphis. Railway Age Gazette. 23 April:645-649. Casteel, Britt 1980 Homesteading on the Cumberland Plateau. The Courier. 18(3):4-5. Chamberlain, William 1983 The Cleft-ridge Span: America's First Concrete Arch. Journal of the Society for Industrial Archaeology. 9:29-44. Comp,T.Allan and Donald Jackson 1977 Bridge Truss Types: A Guide to Dating and Identifying. American Association for State and Local History Technical Leaflet 95, History News,Volume 32, No. 5, May. Nashville. Construction Methods 1932 Double-Rib Arches of Tennessee River Bridge are Concreted by Repeated Use of Steel Centering. April:16-19 Creighton, Wilbur F. 1909 Concrete Work on Sparkman St. Bridge, Nashville,Tennessee. Engineering News. SURVEY REPORT FOR HISTORIC HIGHWAY BRIDGES HIGHWAY FOR HISTORIC REPORT SURVEY 25 February, 61:199-201. 1972 Wilbur Fisk Foster: Soldier and Engineer. Tennessee Historical Quarterly. 31:261- 275. Delony, Eric 1994 The Golden Age. Invention and Technology. Fall:8-22. Delony, Eric and Michael Auer 1990 Bibliography of State Historic Bridge Inventories. Journal of the Society for Industrial Archaeology. -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form REGISTER

NFS Form 10-900-b QMB No 1024-0018 (Jan 1987) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form REGISTER This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bufietin 16). Compfete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing _____Memphis Park and Parkway System__________________________________ B. Associated Historic Contexts _____The City Beautiful Movement and Community Planning 1900 - 1977/1,939 Work of George E. Kessler (1862-1923) "1901-1914 C. Geographical Data All properties are located within the incorporated limits of the City of Memphis, Tennessee See continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Planning and Evaluation. Signature of certifying official f Date •' Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer/Tennessee Historical Commission State or Federal agency and bureau I, hereby, certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluating related properties for listing in the National Register. -

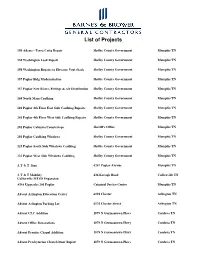

Lotus Approach/LIST of JOBS.APR

List of Projects 150 Adams - Terra Cotta Repair Shelby County Government Memphis TN 150 Washington Leak Repair Shelby County Government Memphis TN 150 Washington Repairs to Elevator Vent Stack Shelby County Government Memphis TN 157 Poplar Bldg Modernization Shelby County Government Memphis TN 157 Poplar New Risers, Fittings & Air Distribution Shelby County Government Memphis TN 160 North Main Caulking Shelby County Government Memphis TN 201 Poplar 4th Floor East Side Caulking Repairs Shelby County Government Memphis TN 201 Poplar 4th Floor West Side Caulking Repairs Shelby County Government Memphis TN 201 Poplar Cabinets/Countertops Sheriff's Office Memphis TN 201 Poplar Caulking Windows Shelby County Government Memphis TN 225 Poplar South Side Windows Caulking Shelby County Government Memphis TN 225 Poplar West Side Windows Caulking Shelby County Government Memphis TN A T & T Sign 6267 Poplar Avenue Memphis TN A T & T Mobility 434 Keough Road Collierville TN Collierville MTSO Expansion ADA Upgrades 201 Poplar Criminal Justice Center Memphis TN Advent Arlington Education Center 6194 Chester Arlington TN Advent Arlington Parking Lot 6176 Chester Street Arlington TN Advent CLC Addition 1879 N Germantown Pkwy Cordova TN Advent Office Renovations 1879 N Germantown Pkwy Cordova TN Advent Prentiss Chapel Addition 1879 N Germantown Pkwy Cordova TN Advent Presbyterian Church Door Repair 1879 N Germantown Pkwy Cordova TN List of Projects Advent Presbyterian Church New NW Parking Lot 1879 N Germantown Pkwy Cordova TN Advent Presbyterian Church -

Good Roads Everywhere: a History of Road Building in Arizona

GOODGGOODGOOOODD ROADSRROADSROOAADDSS EVERYWHERE:EEVERYWHERE:EVVEERRYYWWHHEERREE:: A HistoryHistory ofof RoadRoad BuildingBuilding inin ArizonaArizona prepared for prepared for Arizona Department of Transportation Environmental Planning Group May 2003 Cover Photograph U.S. Highway 66 at Gold Road, circa 1930s Norman Wallace, Photographer (Courtesy of Arizona Department of Transportation) GOOD ROADS EVERYWHERE: A HISTORY OF ROAD BUILDING IN ARIZONA prepared for Arizona Department of Transportation Environmental Planning Section 205 South 17th Avenue Phoenix, Arizona 85007 Project Number STP-900-0(101) TRACS #999 SW 000 H3889 01D Contract Number 97-02 URS Job 23442405 prepared by Melissa Keane J. Simon Bruder contributions by Kenneth M. Euge Geological Consultants, Inc. 2333 West Northern Avenue, Suite 1A Phoenix, Arizona 85021 revisions by A.E. (Gene) Rogge URS Corporation 7720 N. 16th Street, Suite 100 Phoenix, Arizona 85020 URS Cultural Resource Report 2003-28(AZ) March 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ...................................................................................................................................... iv List of Figures..................................................................................................................................... iv List of Pocket Maps............................................................................................................................ v Foreword (by Owen Lindauer and William S. Collins).................................................................... -

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet Section Number ^ Page 1___ Hein Park Historic District

6 NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10244018 (Rev. 8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900a). Type all entries. 1. Name of Property________________________________________________ historic name Hein Park Historic District other names/site number N/A 2. Location street & number roughly bounded by N. Parkway, Trezevant, Jackson, N/^ not for publication city, town Memphis West, & Charles N/ltA_J vicinity state Tennessee code TN county Shelby code 157 zip code 38112 3. Classification Ownership of Property Category of Property Number of Resources within Property Ecxl private I I building(s) Contributing Noncontributing PI public-local Rxl district 276 54 buildings I I public-State I I site ____ sites I I public-Federal I I structure ____ structures I I object ____ objects 278 54 Total Name of related multiple property listing: Number of contributing resources previously _______N/A_____________ listed in the National Register ___0 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this [H nomination EH request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Detailed Spreadsheet INTERNAL in PROGRESS.Xlsx

AB C DE F GHI 1 Ref# Historic Name Other Name(s) County City Address Address Restricted Multiple Name Listing Date 2 76001760 Arnwine Cabin Anderson Norris TN 61 3/16/1976 3 92000411 Bear Creek Road Checking Station Anderson Oak Ridge Jct. of S. Illinois Ave. and Bear Creek Rd. Oak Ridge MPS 5/6/1992 4 92000410 Bethel Valley Road Checking Station Anderson Oak Ridge Jct. of Bethel Valley and Scarboro Rds. Oak Ridge MPS 5/6/1992 5 91001108 Brannon, Luther, House Hackworth,Owen,House Anderson Oak Ridge 151 Oak Ridge Tpk. Oak Ridge MPS 9/5/1991 6 03000697 Briceville Community Church and Cemetery Briceville Methodist Church Anderson Briceville TN 116 7/24/2003 7 06000134 Cross Mountain Miners' Circle Circle Cemetery; Laurel Branch Cemetery Anderson Briceville Circle Cemetery Ln. 3/15/2006 8 10000936 Daugherty Furniture Building Daugherty, J.R., Company Anderson Clinton 307 N Main St 11/29/2010 9 75001726 Edwards‐‐Fowler House Anderson Rocky Top (formerly Lake City) 3.5 mi. S of Lake City on Dutch Valley Rd. 5/29/1975 10 11000830 Fort Anderson on Militia Hill Anderson Rocky Top (formerly Lake City) Vowell Mountain Rd. 11/21/2011 11 04001459 Fraterville Miners' Circle Cemetery Leach Cemetery Anderson Rocky Top (formerly Lake City) Leach Cemetery Ln. 1/5/2005 12 92000407 Freels Cabin 40AN28 Anderson Oak Ridge Freels Bend Rd. Oak Ridge MPS 5/6/1992 13 91001107 Jones, J. B., House Daniel Arthur Rehabilitation Center (DARC) Farm #2 Anderson Oak Ridge Old Edgemoor Rd. between Bethel Valley Rd. and Melton Hill Lake Oak Ridge MPS 9/5/1991 14 05001218 McAdoo, Green, School Clinton Colored School; McAdoo, Green, Grammar School Anderson Clinton 101 School St. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPSForm 10-900 OMBNo. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form — •••• ' ' ' This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual proplltie»:and.1districts. See instructions Jn How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by maifcirig V in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A*-foCn,.bt applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property___________________________________________________ historic name Galloway-Speedway Historic District_______________________________ other names/site number NA__________________________________________ 2. Location street & number N. Parkway, Faxon, Greenlaw, Galloway, and Forrest Avenues NAQ not for publication city or town Memphis_____________________________ ___ D vicinity N/A state Tennessee code TN county Shelby code 157 zip code 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this E3 nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set for in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ^ meets D does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered .significant D nationally Q statewide £3 locally. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NFS Form 10-900 QMS Mo. 1024-0018 (Rev. 8-86) o United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places MAY i 91989 Registration Form NATIONAL This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. laiolrlSlroclions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900a). Type all entries. 1. Name of Property________________________________________________ historic name___M^mph i g Pa rlcwa y fiyRt- <=»m___________________________________________ other names/site number TJ/A 2. Location PaT-lrw, N street & number ooay- W P! P iot for publication city, town icinity state code county QbolHi code R7 zip code 3. Classification Ownership of Property Category of Property Number of Resources within Property E3 private I I building(s) Contributing Noncontributing Qpublic-local Pxl district ____ ____ buildings Qpublic-State I | site ____ ____ sites I I public-Federal I I structure Q a structures I I object ____ ____ objects Name of related multiple property listing: Number of contributing resources previously foJLS Park and Parkway System listed in the National Register 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this SH nomination EH request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

National Register of Historic Places 1989 Weekly Lists

•.1 TAKE • PRIDEIN United States Department of the Interior AMERICA - NATIONAL PARK SERVICE P.O. BOX 37127 I!>-- -. WASHINGTON, D.C. 20013·7127 IN REPLY REFER TO: The Director of the National Park Service is pleased to inform you that the following properties have been entered in the National Register of Historic Places. For further information call 202/343-9542. JUL G7 1989 WEEKLY LIST OF LISTED PROPERTIES 6/26/89 THROUGH 6/30/89 KEY: Property Name, Multiple Name, Address/Boundary, city, Vicinity, Certification Date, Reference Number, NHL status ALABAMA Lee County Yarbrough, Franklin, Jr., Store Co. Hwy. 68 Beaulah vicinity 6/29/89 89000309 INDIANA Clark County French, Henry, House 217 E. High St. Jeffersonville 6/29/89 89000772 Orange County Braxtan, Thomas Newby, House 210 N. Gospel st. Paoli 6/29/89 89000777 Rush county Reeves, Jabez, Farmstead Co. Rd. 900 N. Rushville vicinity 6/29/89 89000776 Vanderburgh County Bernardin--Johnson House 17 Johnson Pl. Evansville 6/27/89 89000238 IOWA Boone County First National Bank Architectural Legacy of Proudfoot and Bird in Iowa, 1882--19 40 MPS 8th and Story Sts. Boone 6/28/89 88003232 •·IOWA Boone County Herman, John H., House Architectural Legacy of Proudfoot and Bird in Iowa, 1882--19 40 MPS 711 s. story st. Boone 6/28/89 88003233 MICHIGAN Oakland County Casa del Rey Apartments 111 Oneida Rd. Pontiac 6/29/89 89000787 Wayne County st. Thomas the Apostle catholic Church and Rectory 8363--8383 Townsend Ave. Detroit 6/29/89 89000785 MISSISSIPPI Adams County Oakland Lower Woodville Rd.