The Case of Fiji

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender Politics in the Asia-Pacific Region

Gender Politics in the Asia-Pacific Region Amidst the unevenness and unpredictability of change in the Asia-Pacific region, women’s lives are being transformed. This volume takes up the challenge of exploring the ways in which women are active players, collaborators, partici- pants, leaders and resistors in the politics of change in the region. The contributors argue that ‘gender’ matters and continues to make a differ- ence in the midst of change, even as it is intertwined with questions of tradition, generation, ethnicity and nationalism. Drawing on current dialogue among femi- nism, cultural politics and geography, the book focuses on women’s agencies and activisms, insisting on women’s strategic conduct in constructing their own multiple identities and navigation of their life paths. The editors focus attention on the politics of gender as a mobilising centre for identities, and the ways in which individualised identity politics may be linked to larger collective emancipatory projects based on shared interests, practical needs or common threats. Collectively, the chapters illustrate the complexity of women’s strategies, the diversity of sites for action, and the flexibility of their alliances as they carve out niches for themselves in what are still largely patriar- chal worlds. This book will be of vital interest to scholars in a range of subjects, including gender studies, human geography, women’s studies, Asian studies, sociology and anthropology. Brenda S.A. Yeoh is an Associate Professor in the Department of Geography, National University of Singapore. Her research foci include the politics of space in colonial and post-colonial cities, and gender, migration and transnational communities. -

A Socio-Cultural Investigation of Indigenous Fijian Women's

A Socio-cultural Investigation of Indigenous Fijian Women’s Perception of and Responses to HIV and AIDS from the Two Selected Tribes in Rural Fiji Tabalesi na Dakua,Ukuwale na Salato Ms Litiana N. Tuilaselase Kuridrani MBA; PG Dip Social Policy Admin; PG Dip HRM; Post Basic Public Health; BA Management/Sociology (double major); FRNOB A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2013 School of Population Health Abstract This thesis reports the findings of the first in-depth qualitative research on the socio-cultural perceptions of and responses to HIV and AIDS from the two selected tribes in rural Fiji. The study is guided by an ethnographic framework with grounded theory approach. Data was obtained using methods of Key Informants Interviews (KII), Focus Group Discussions (FGD), participant observations and documentary analysis of scripts, brochures, curriculum, magazines, newspapers articles obtained from a broad range of Fijian sources. The study findings confirmed that the Indigenous Fijian women population are aware of and concerned about HIV and AIDS. Specifically, control over their lives and decision-making is shaped by changes of vanua (land and its people), lotu (church), and matanitu (state or government) structures. This increases their vulnerabilities. Informants identified HIV and AIDS with a loss of control over the traditional way of life, over family ties, over oneself and loss of control over risks and vulnerability factors. The understanding of HIV and AIDS is situated in the cultural context as indigenous in its origin and required a traditional approach to management and healing. -

Fiji's Road to Military Coup, 20061

2. 'Anxiety, uncertainty and fear in our land': Fiji's road to military coup, 20061 Brij V. Lal Introduction If civilization is to survive, one is driven to radical views. I do not mean driven to violence. Violence always compromises or ruins the cause it means to serve: it produces as much wrong as it tries to remedy. The State, for example, is always with us. Overthrow it and it will come back in another form, quite possibly worse. It's a necessary evilÐa monster that continually has to be tamed, so that it serves us rather than devours us. We can't do without it, neither can we ever trust it.2 Fiji experienced the whole gamut of emotions over the course of a fateful 2006. The year ended on an unsettled note, as it had begun. Fiji was yet again caught in a political quagmire of its own making, hobbled by manufactured tensions, refusing to heed the lessons of its recent tumultuous past, and reeling from the effects of the coup. Ironies abound. A Fijian army confronted a Fijian government, fuelling the indigenous community's worst fears about a Fijian army spilling Fijian blood on Fijian soil. The military overthrow took place 19 years to the day after frustrated coup-maker of 1987 Sitiveni Rabuka had handed power back to Fiji's civilian leaders, Ratu Sir Penaia Ganilau and Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara, paving the way for the eventual return to parliamentary democracy. The 2006 coup, like the previous ones, deposed a democratically elected government. Perhaps more importantly, it peremptorily sidelined the once powerful cultural and social institutions of the indigenous community, notably the Methodist Church and the Great Council of Chiefs (GCC)3 ± severing with a startling abruptness the overarching influence they had exercised in national life. -

The Case of Fiji

University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform Volume 25 Issues 3&4 1992 Democracy and Respect for Difference: The Case of Fiji Joseph H. Carens University of Toronto Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Cultural Heritage Law Commons, Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Recommended Citation Joseph H. Carens, Democracy and Respect for Difference: The Case of Fiji, 25 U. MICH. J. L. REFORM 547 (1992). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr/vol25/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEMOCRACY AND RESPECT FOR DIFFERENCE: THE CASE OF FIJI Joseph H. Carens* TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................. 549 I. A Short History of Fiji ................. .... 554 A. Native Fijians and the Colonial Regime .... 554 B. Fijian Indians .................. ....... 560 C. Group Relations ................ ....... 563 D. Colonial Politics ....................... 564 E. Transition to Independence ........ ....... 567 F. The 1970 Constitution ........... ....... 568 G. The 1987 Election and the Coup .... ....... 572 II. The Morality of Cultural Preservation: The Lessons of Fiji ................. ....... 574 III. Who Is Entitled to Equal Citizenship? ... ....... 577 A. The Citizenship of the Fijian Indians ....... 577 B. Moral Limits to Historical Appeals: The Deed of Cession ............. ....... 580 * Associate Professor of Political Science, University of Toronto. -

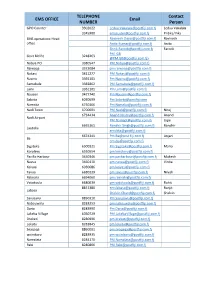

EMS Operations Centre

TELEPHONE Contact EMS OFFICE Email NUMBER Person GPO Counter 3302022 [email protected] Ledua Vakalala 3345900 [email protected] Pritika/Vika EMS operations-Head [email protected] Ravinesh office [email protected] Anita [email protected] Farook PM GB Govt Bld Po 3218263 @[email protected]> Nabua PO 3380547 [email protected] Raiwaqa 3373084 [email protected] Nakasi 3411277 [email protected] Nasinu 3392101 [email protected] Samabula 3382862 [email protected] Lami 3361101 [email protected] Nausori 3477740 [email protected] Sabeto 6030699 [email protected] Namaka 6750166 [email protected] Nadi Town 6700001 [email protected] Niraj 6724434 [email protected] Anand Nadi Airport [email protected] Jope 6665161 [email protected] Randhir Lautoka [email protected] 6674341 [email protected] Anjani Ba [email protected] Sigatoka 6500321 [email protected] Maria Korolevu 6530554 [email protected] Pacific Harbour 3450346 [email protected] Mukesh Navua 3460110 [email protected] Vinita Keiyasi 6030686 [email protected] Tavua 6680239 [email protected] Nilesh Rakiraki 6694060 [email protected] Vatukoula 6680639 [email protected] Rohit 8812380 [email protected] Ranjit Labasa [email protected] Shalvin Savusavu 8850310 [email protected] Nabouwalu 8283253 [email protected] -

Melanesia in Review: Issues and Events, 2000

Melanesia in Review: Issues and Events, 2000 Reviews of Papua New Guinea and tion of May 1999, became more overt West Papua are not included in this in the early months of 2000. Fijian issue. political parties, led by the former governing party, Soqosoqo ni Vakavu- Fi j i lewa ni Taukei (sv t), held meetings For the people of Fiji, the year 2000 around the country to discuss ways to was the most turbulent and traumatic oppose if not depose the government in recent memory. The country and thereby return to power. These endured an armed takeover of parlia- meetings helped fuel indigenous Fijian ment and a hostage crisis lasting fifty- unease and animosity toward Chaud- six days, the declaration of martial hry’s leadership. Signaling its move law and abrogation of the 1997 con- toward a more nationalist stance, the stitution, and a bloody mutiny in the sv t terminated its coalition with the armed forces. These events raised the Indo-Fijian–based National Federa- specter of civil war and economic col- tion Party in February, describing the lapse, international ostracism, and a coalition as “self-defeating.” future plagued with uncertainty and In March, the Taukei Movement ha r dship. Comparisons with the coups was revived with the aim, according of 1987 were inevitable, but most to spokesman Apisai Tora, of “rem o v - observers would conclude that the ing the government through various crisis of 2000 left Fiji more adrift legal means as soon as possible” (Sun, and divided than ever before. 3 May 2000, 1). In 1987 the Taukei The month of May has become Movement had spearheaded national- synonymous with coups in Fiji. -

History of Inter-Group Conflict and Violence in Modern Fiji

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sydney eScholarship History of Inter-Group Conflict and Violence in Modern Fiji SANJAY RAMESH MA (RESEARCH) CENTRE FOR PEACE AND CONFLICT STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY 2010 Abstract The thesis analyses inter-group conflict in Fiji within the framework of inter-group theory, popularised by Gordon Allport, who argued that inter-group conflict arises out of inter-group prejudice, which is historically constructed and sustained by dominant groups. Furthermore, Allport hypothesised that there are three attributes of violence: structural and institutional violence in the form of discrimination, organised violence and extropunitive violence in the form of in-group solidarity. Using history as a method, I analyse the history of inter-group conflict in Fiji from 1960 to 2006. I argue that inter- group conflict in Fiji led to the institutionalisation of discrimination against Indo-Fijians in 1987 and this escalated into organised violence in 2000. Inter-group tensions peaked in Fiji during the 2006 general elections as ethnic groups rallied behind their own communal constituencies as a show of in-group solidarity and produced an electoral outcome that made multiparty governance stipulated by the multiracial 1997 Constitution impossible. Using Allport’s recommendations on mitigating inter-group conflict in divided communities, the thesis proposes a three-pronged approach to inter-group conciliation in Fiji, based on implementing national identity, truth and reconciliation and legislative reforms. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis is dedicated to the Indo-Fijians in rural Fiji who suffered physical violence in the aftermath of the May 2000 nationalist coup. -

Fiji Meteorological Service Government of Republic of Fiji

FIJI METEOROLOGICAL SERVICE GOVERNMENT OF REPUBLIC OF FIJI MEDIA RELEASE No. 13 1pm, Wednesday, 16 December, 2020 SEVERE TC YASA INTENSIFIES FURTHER INTO A CATEGORY 5 SYSTEM AND SLOW MOVING TOWARDS FIJI Warnings A Tropical Cyclone Warning is now in force for Yasawa and Mamanuca Group, Viti Levu, Vanua Levu and nearby smaller islands and expected to be in force for the rest of the group later today. A Tropical Cyclone Alert remains in force for the rest Fiji A Strong Wind Warning remains in force for the rest of Fiji. A Storm Surge and Damaging Heavy Swell Warning is now in force for coastal waters of Rotuma, Yasawa and Mamanuca Group, Viti Levu, Vanua Levu and nearby smaller islands. A Heavy Rain Warning remains in force for the whole of Fiji. A Flash Flood Alert is now in force for all low lying areas and areas adjacent to small streams along Komave to Navua Town, Navua Town to Rewa, Rewa to Korovou and Korovou to Rakiraki in Vanua Levu and is also in force for all low lying areas and areas adjacent to small streams of Vanua Levu along Bua to Dreketi, Dreketi to Labasa and along Labasa to Udu Point. Situation Severe tropical cyclone Yasa has rapidly intensified and upgraded further into a category 5 system at 3am today. Severe TC Yasa was located near 14.6 south latitude and 174.1 east longitude or about 440km west-northwest of Yasawa-i-Rara, about 500km northwest of Nadi and about 395km southwest of Rotuma at midday today. The system is currently moving eastwards at about 6 knots or 11 kilometers per hour. -

4.3 Fiji Port and Waterways Company Contact List Fiji Port and Waterways Company Contact List

4.3 Fiji Port and Waterways Company Contact List Fiji Port and Waterways Company Contact List Port Name Company Physical Address Website & Email Phone Number (office & Fa Description of Duties mobile) x N u m ber All Fiji Fiji Ports n/a http://www.portofsuva. +679 6662160 +6 Port Management Ports Corporation com 79 Limited 66 65 799 All Bollore 8-9 Freeston Road, Walu Bay, Chandima +679 3315044 +6 Transporter, shipping, storage: (Pacific Logistics Suva, Fiji Gunawardana, General 79 Island (Fiji) Ltd Manager. chandima. Shipping: MV Internatio gunawardana@bollor e. 33 nal Ports) com 15 Subritzky 120 MT, cargo capacity. MV, 055 Kusima 110 MT, cargo capacity MV, Mobile: +679 9994869 Kawai 115 MT, cargo capacity Ronald Dass, Manager Operations. Ronald [email protected] Mobile: +679 9905910 All (Fiji Fiji Ports n/a http://www.portofsuva. +679 6662160 +6 Port Management Ports) Corporation com 79 Limited 66 65 799 All / Suva Government Governments Wharf iliesa. Freight Superintendent: Mr. n Govt Only Shipping Shipping [email protected] Iliesa Raketekete /a Services Off Amra Street, Walu Bay, http://www. (GSS) Suva governmentshipping.gov. Tel: +679 3312246 fj Mobile: +6793314561 Port of Sea Road Fiji Seaboard Service pattersonship@connect. Sanjay Prasad n Shipping Schedule - Patterson Brothers S Suva Patterson (Patterson Brothers Seaboard com.fj /a eaboard Shipping co Brothers Shipping Co Ltd) Suite 182, + 679 3315644 Seaboard Epwoth House, Nina Street, Shipping co. Suva, Fiji. +6799221335 Port of Goundar Lot 22, Freeston Road, Walu goundarshipping@kidane Tel: + 679 3301060 n Shipping Schedule - Goundar Shipping Suva Shipping co. Bay, Suva. t.com.fj /a co Mobile: +6797775471 (Rakesh) +679 7775462 (Krishna) Vanua Wharf off Amra Street, Walu http://www. -

Issues and Events, I992

.1 , • , Melanesia in Review: Issues and Events, I992 FIJI Fijians and non-Indo-Fijians, won all The year 1992 may well be remembered the 5 seats allocated to that community. in Fiji as one of unexpected develop In an unexpectedly close contest, the ments in the political arena, dominated National Federation Party won 14 of by the general election in May. The the 27 seats allocated to the Indo-Fijian first half of the year was consumed by community, with the Fiji Labour Party the election campaign and the second securing 13. The Soqosoqo ni Vakavu half by its problematic reverberations. lewa ni Taukei was able to form a gov It ended with a promise to take Fiji ernment after entering into a coalition away from the politics ofracial divi with the General Voters Party and with sion toward a multiracial government the support of the Fijian National ofnational unity. Whether, and if, that United Front. Sitiveni Rabuka became occurs will be the challenge of1993. prime minister after Labour threw its The general election, the sixth since support behind him rather than Kami independence in 1970 and the first since kamica, who was backed by the the coups of1987, was preceded by a National Federation Party. long and sometimes bitter campaign Labour's strategy took supporters (see my article, this issue). Political completely by surprise. Its leaders fragmentation in the Fijian community argued that Rabuka was a changed accompanied the emergence of a num man who appeared to be a genuine ber ofpolitical parties and the rise of friend ofthe poor of all races. -

FIJI Dates of Elections: 10 to 17 July 1982 Purpose of Elections

FIJI Dates of Elections: 10 to 17 July 1982 Purpose of Elections Elections were held for all the seats in the House of Representatives on the normal expiry of the members' term of office. Characteristics of Parliament The bicameral Parliament of Fiji is composed of a Senate and a House of Represen tatives. The Senate consists of 22 members appointed by the Governor-General, of whom: - 8 nominated by the Great Council of Chiefs; - 7 nominated by the Prime Minister; - 6 nominated by the Leader of the Opposition; - 1 nominated by the Council of the Island of Rotuma. Appointements are for 6 years, 11 members retiring every 3 years. The House of Representatives consists of 52 members elected for 5 years on the following basis; - Fijian: 12 members elected by voters on the Fijian Communal Roll; 10 members elected by voters on the National Roll. - Indian: 12 members elected by voters on the Indian Communal Roll: 10 members elected by voters on the National Roll. - General (persons neither Fijian nor Indian): 3 members elected by voters on the General Communal Roll; 5 members elected by voters on the National Roll. The "National Roll" consists of all registered electors on the three Communal Rolls. Electoral System Any person may be registered as elector on a Roll if he is a citizen of Fiji and has attained the age of 21 years. The insane, persons owing allegiance to a State outside the British Commonwealth, those under sentence of death or imprisonment for a term exceeding 12 months and those convicted of electoral offences may not be registered. -

Researchspace@Auckland

http://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz ResearchSpace@Auckland Copyright Statement The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). This thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: • Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. • Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author's right to be identified as the author of this thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. • You will obtain the author's permission before publishing any material from their thesis. To request permissions please use the Feedback form on our webpage. http://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/feedback General copyright and disclaimer In addition to the above conditions, authors give their consent for the digital copy of their work to be used subject to the conditions specified on the Library Thesis Consent Form and Deposit Licence. CONNECTING IDENTITIES AND RELATIONSHIPS THROUGH INDIGENOUS EPISTEMOLOGY: THE SOLOMONI OF FIJI ESETA MATEIVITI-TULAVU A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY The University of Auckland Auckland, New Zealand 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract .................................................................................................................................. vi Dedication ............................................................................................................................