Using Role Method and Therapeutic Circus Arts with Adults to Create a Meaningful Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emilia Sonalii Selena Fernandez Alignment: Unprincipled P.C.C.: Fire Walker Occupation: Fire Dancer/Performer, Singer & Violinist

Emilia Sonalii Selena Fernandez Alignment: Unprincipled P.C.C.: Fire Walker Occupation: Fire Dancer/Performer, Singer & Violinist Excerpts for Emilia’s journal (translated from Spanish): “We buried papi this morning. It was a simple service. I think he’d have preferred that. When I gave my goodbyes to everyone who attended, I gave them for possibly forever. That thing that killed papi… they call it a “Dar’ota” … I overheard its master say they were “going up to ‘Seattle’ for business” (in English), which is a city in America; way up north, close to Canada. But if that’s where it is going, then so am I. I packed my things before the funeral, and I started heading north as soon as I left. I don’t know why it killed papi, but I will avenge him. I know that vengeance is a sin, but justice is not. Mexico City has always been my home, and I’ve never left my family. The idea of leaving behind my home and my family behind is terrifying. But I’m determined to the find that thing and destroy it, no matter what. I writing in this journal so in case I don’t come home, my family might understand why.” “I am in Seattle. It has taken me weeks to get here, but I did it. It is very different from Mexico City. There are so many trees here. The sky is steel gray, overcast and rainy most days. I can see mountains with snow on them in the distance. The people here are very different, but they are interesting and they are kind to me. -

Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday

Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Swinging Trapeze 1000-01 2:30-3:30PM Swinging Trapeze 1000-02 2:00-3:00PM Hammock 0200-02 3:00-3:30PM Swinging Trapeze 1000-02 2:45-3:30PM Swinging Trapeze 1000-01 2:15-3:15PM 9:00 AM Wings 0000-01 2:30-3:45PM Cloud Swing 1000-01 2:30-3:00PM Revolving Ladder 1000-01 3:15-4:00PM Double Trapeze 0100-04 3:30-4:15PM Duo Trapeze 0100-01 3:15-4:00PM Flying Trapeze 0000-02 3:00 PM 3:00 Mexican Cloud Swing 0100-02 3:30-4:15PM Pas de Deux 0000-01 3:00-4:00PM Swinging Trapeze 0100-02 3:15-4:00PM Handstands 1000-01 3:30-4:15PM Duo Trapeze 0100-03 3:15-4:00PM Globes 0000-01 Swinging Trapeze 0100-01 3:30-4:15PM Double Trapeze 0100-02 3:15-4:00PM Triangle Trapeze 1000-01 3:30-4:15PM Chair Stacking 1000-01 Triangle Trapeze 0100-02 3:15-4:00PM Low Casting Fun 0000-04 4-Girl Spinning Cube 1000-01 3:45-4:30PM Duo Trapeze 0100-02 3:30-4:15PM Static Trapeze 1000-01 4-Girl Spinning Cube 0000-01 3:30-4:00PM Mini Hammock 0000-02 Handstands 1000-01 Manipulation Cube 0000-01 3:30-4:00PM Star 0100-01 High Wire 1000-01 Stilt Walking 1000-01 3:30-4:25PM Toddlers 0200-03 ages 3-4 Mexican Cloud Swing 0100-02 3:30-4:15PM Acrobatics 0205-01 ages 10+ Triangle Trapeze 1000-01 3:30-4:15PM Double Trapeze 0100-04 3:30-4:15PM Stilt Walking 1000-01 3:30-4:25PM Trampoline 0000-04 ages 6-9 Swinging Trapeze 0100-01 3:30-4:15PM Bungee Trapeze 0300-01 Cloud Swing 0100-02 4:00-4:30PM Handstands 1000-01 3:30-4:15PM Duo Hoops 1000-01 4:00-4:30PM 4:00 PM 4:00 4-Girl Spinning Cube 1000-01 3:45-4:30PM Circus Spectacle 0100-01 Pas de Deux -

The Beginner's Guide to Circus and Street Theatre

The Beginner’s Guide to Circus and Street Theatre www.premierecircus.com Circus Terms Aerial: acts which take place on apparatus which hang from above, such as silks, trapeze, Spanish web, corde lisse, and aerial hoop. Trapeze- An aerial apparatus with a bar, Silks or Tissu- The artist suspended by ropes. Our climbs, wraps, rotates and double static trapeze acts drops within a piece of involve two performers on fabric that is draped from the one trapeze, in which the ceiling, exhibiting pure they perform a wide strength and grace with a range of movements good measure of dramatic including balances, drops, twists and falls. hangs and strength and flexibility manoeuvres on the trapeze bar and in the ropes supporting the trapeze. Spanish web/ Web- An aerialist is suspended high above on Corde Lisse- Literally a single rope, meaning “Smooth Rope”, while spinning Corde Lisse is a single at high speed length of rope hanging from ankle or from above, which the wrist. This aerialist wraps around extreme act is their body to hang, drop dynamic and and slide. mesmerising. The rope is spun by another person, who remains on the ground holding the bottom of the rope. Rigging- A system for hanging aerial equipment. REMEMBER Aerial Hoop- An elegant you will need a strong fixed aerial display where the point (minimum ½ ton safe performer twists weight bearing load per rigging themselves in, on, under point) for aerial artists to rig from and around a steel hoop if they are performing indoors: or ring suspended from the height varies according to the ceiling, usually about apparatus. -

Xochitl Sosa- Circus Performer 2126 Emerson St Berkeley, CA 94705 Phone: (510)219-5157 E-Mail: [email protected]

Xochitl Sosa- Circus Performer 2126 Emerson st Berkeley, CA 94705 Phone: (510)219-5157 www.xochitlsosa.com E-mail: [email protected] Skills Dance Trapeze – Static Trapeze - Silks – Rope/Corde Lisse – Duo Trapeze – Straps – Acrobatics – Lyra/Cerceaux – Partner acrobatics – Stilting – Modern Dance Height: 5’5” Weight: 127 lbs Hair Color: Brown Experience Acrobatic Conundrum: Dance Trapeze, Duo Trapeze, Rope, partner acrobatics, acting (USA tour) 2016 Rolling in the Hay Cabaret: Dance trapeze (San Francisco, CA) 2015 Circovencion Mexicana: Performer on Dance Trapeze & Workshop instructor (Oaxtepec,Morelos MX) 2015 Yerba Buena Night: Performer on Dance Trapeze & Rope (San Francisco, CA) 2014-2015 Hardly Strictly Bluegrass Festival: Performer on Silks (San Francisco, CA) 2015 Topsy Turvy Queer arts Festival: Performer on Dance Trapeze (San Francisco, CA) 2015 Aerial Acrobatics Festival: Performer on Dance Trapeze (Denver,CO) 2014 Aerial Horizon: Performer on Dance Trapeze (San Antonio, TX) 2014 Crash Alchemy/ AgentRed: Dancer, Lyra, Trapeze, Partner Acrobatics, Contortion (USA) 2010-2015 Sky Candy Productions: Trapeze, Duo trapeze, Dancer, partner acrobatics, instructor (Austin,TX) 2010-2015 NASCAR’s Wild Asphalt Circus – Hellzapoppin Sideshow: Static Trapeze, Silks (Dallas,TX) 2013 Formula One Inaugeration: OMEGA events: Duo Trapeze, Static Trapeze (Austin,TX) 2012 Education Leslie Tipton: Contortion San Francisco, CA 2015 Chloe Farah: Duo Trapeze, Dance Trapeze, Rope Montreal, Canada 2015 Itzel Virguenza: Duo Trapeze, Dance Trapeze Montreal, Canada 2015 Victor Fomine: Straps Montreal, Canada 2015 Serchmaa Byamba: Contortion San Francisco, CA 2014-2015 Rachel Walker: Dance Trapeze Montreal , Canada 2013 NECCA Protrack Program Brattleboro, Vermont 2012-2013 (coaches: Aimee Hancock, Elsie & Serenity Smith, Bill Forchion, Sellam Ouahabi) NECCA Bootcamp Brattleboro, Vermont 2011 Sky Candy Austin Austin, TX 2010- 2014 Camp Winnarainbow (coahing under: Carrie Heller) Laytonville, CA summers 2000- 2009 2 . -

Oregon Science Tour Sample Itinerary

Oregon Science Tour Sample Itinerary Day One Day Three Morning Morning Arrive in Portland, OR Deschutes River Rafting Climb into a raft for a 13 mile, 3.5 hour exciting ride! The Deschutes is known throughout Afternoon the United States as a premier river for white water rafting, fishing, kayaking, hiking and Oregon Zoo beautiful scenery. The Oregon Zoo is a rich ecosystem of conservation, animal care, enrichment and education. Observe and learn about plants and animals of the Pacific Northwest as well as from around Afternoon the world. Bonneville Day ZooSchool Visit the Bonneville Dam and Fish Ladder and learn about this Columbia River hydropower Learn how zookeepers communicate with animals and use training to keep the animals system from an Oregon Tribes perspective. You’ll hear about the history of the river and its active in both mind and body. You will get the chance try your hand at animal training. relationship with both the environment and the people past and present. Hike in the Hoyt Arboretum Columbia River Hike to Multnomah Falls, the second highest in the United States, and several others in this Voodoo Donuts beautiful area of the Columbia River Gorge. A yummy must-do in Portland. If there was ever a business that captured the kooky essence of Portland, it’s Voodoo. Sweet-fingered magicians concoct what might best be described as Evening avant-garde doughnuts. Overnight in Hood River Evening Overnight in Hood River (On the Columbia River) Day Four The Columbia River is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest . It is 1,243 miles long and extends into seven US states and a Canadian Province. -

Fire Performance Art Permit

Policy Grants Pass Department of Public Safety 4XX Fire Policy Manual Fire Performance Art Permit 4XX.1 PURPOSE AND SCOPE The purpose of this policy is to provide guidelines to advise fire performance venues and artists of safety considerations and practices consistent with fire and life safety codes and public assembly safety concerns. 4XX.2 POLICY This policy applies to all acts of fire performance art occurring within all areas in which Grants Pass Department of Public Safety has authority. Fire art refers to performances or demonstrations such as fire breathing, fire juggling, fire dancing, etc. Not included: pyrotechnics and flame effects (these are addressed in a different policy and require a separate permit). The business owner, event coordinator and the fire performer are responsible for all aspects of fire and life safety. Failure to possess a current permit and follow the minimum requirements set forth in this document may result in revocation of permit, future permits and/or issuing of citation(s). Fire performance artists shall: 1. Be at least 18 years of age. a. EXCEPTION: Performers age 16 to 18 may be allowed at the discretion of the Fire Marshal’s Office with written consent from a parent or legal guardian. They must be under the direct supervision of an adult fire performance troupe leader or instructor. 2. Have valid, state issued identification and Fire Performance Permit readily accessible at each performance. 3. Audience: It should be recognized that audiences, especially youthful ones, may not fully understand the dangers associated with fire performance art. Every effort should be made to emphasize the safety precautions and dangers of such activity. -

Janice Aria Was the Second Presenter on the Second Day of the NAIA Conference

Janice Aria was the second presenter on the second day of the NAIA Conference. She began her presentation knowing she had very interesting and “tough” acts to follow. She had no need to worry ‐ ‐ this dynamic woman had us spellbound; she is a consummate entertainer. Originally from Oakhurst, NJ, Jan began her career with Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey in 1972 when she left her last semester at New York University and applied to Ringling Bros. Clown College. Upon graduation, she got a contract with prestigious Ringling Bros. and that was the beginning of a love affair. She told us that it fulfilled a dream ‐‐ to ride up on top of those wonderful elephants. She was especially featured with the elephants and bear acts, but she also had trained dog acts with Golden Retrievers of her breeding. She is, of course, a consummate entertainer who toured worldwide. Aria has close to 40 years in animal training and animal behavior, and in 2005, she was named Director of Animal Stewardship. She directs the elephant‐training program for Ringling, teaches training methods to animal handlers, and is involved in the care of the largest herd of Asian elephants in the Western Hemisphere. All of the animals in the circus are “free contact” as opposed to “barrier contact,” which is generally used for animals in other settings. She stressed that the key to having happy animals is finding what they want to do, and training from there. When the Circus arrives by train at each new town, they have The Animal Walk, which is a parade from the train station to the performance venue. -

Fire Producer E-28 Fire Performer E-29

FIRE DEPARTMENT ● CITY OF NEW YORK STUDY MATERIAL FOR THE EXAMINATION FOR CERTIFICATE OF FITNESS FOR Fire Producer E-28 Fire Performer E-29 © 12/2015 New York City Fire Department - All rights reserved 1 Table of Contents NOTICE OF EXAMINATION ............................................................................. 4 ABOUT THE STUDY MATERIAL ...................................................................... 9 Introduction .................................................................................................. 11 a. Worst Case Scenario .......................................................................... 12 b. Definitions ......................................................................................... 13 Class of Flammable and Combustible Liquids Reference Chart ................ 17 Part I. General Information............................................................................ 17 1. Permits .............................................................................................. 17 2. General requirements for Fire Effects ................................................. 18 3. Fire Performances .............................................................................. 19 Part II. Safety, Handling and Use................................................................... 20 1. Clothing, Costumes, Makeup ............................................................. 21 a. Fiber content ..................................................................................... 21 b. Characteristics -

Dust Palace Roving and Installation Price List 2017

ROVING AND INSTALLATION CIRQUE ENTERTAINMENT HAND BALANCE AND CONTORTION One of our most common performance installations is Hand Balance Contortion. Beautiful and graceful this incredible art is mastered by very few, highly skilled performers. Roving or installation spots are only possible for 30 mins at a time and are priced at $950+gst per performer. ADAGIO AND ACROBATICS Adagio, hand to hand, balance acrobatics and trio acro are all ways to describe the art of balancing people on people. Usually performed as a couple this is the same as hand balance contortion in that it’s only possible for 30 minute stints. Roving or installation can be performed in any style and we’re always happy to incorporate your events theme or branding into the theatrics around the skill. Performers are valued at $950+gst per 30 minute slot. MANIPULATION SKILLS Manipulation skills include; Hula Hoops, Juggling, Cigar boxes, Diabolo, Chin Balancing, Poi Twirling, Plate Spinning and Crystal Ball. As a roving or installation act these are fun and lively, bringing some nice speedy movement to the room. All are priced by the ‘performance hour’ which includes 15 minutes break and range between $400+gst and $700+gst depending on the performer and the skill. Some performers are capable of character work and audience interaction. Working these skills in synchronisation with multiple performers is a super cool look. Most of these skills can be performed with LED props. EQUILIBRISTICS aka balance skills The art of balancing on things takes many long hours of dedication to achieve even the most basic result. -

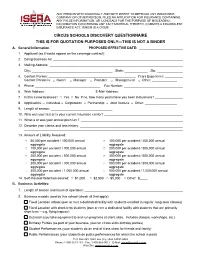

Circus Schools Discovery Questionnaire This Is for Quotation Purposes Only—This Is Not a Binder A

ANY PERSON WHO KNOWINGLY AND WITH INTENT TO DEFRAUD ANY INSURANCE COMPANY OR OTHER PERSON, FILES AN APPLICATION FOR INSURANCE CONTAINING ANY FALSE INFORMATION, OR CONCEALS FOR THE PURPOSE OF MISLEADING, INFORMATION CONCERNING ANY FACT MATERIAL THERETO, COMMITS A FRAUDULENT INSURANCE ACT, WHICH IS A CRIME. CIRCUS SCHOOLS DISCOVERY QUESTIONNAIRE THIS IS FOR QUOTATION PURPOSES ONLY—THIS IS NOT A BINDER A. General Information PROPOSED EFFECTIVE DATE: 1. Applicant (as it would appear on the coverage contract): 2. Doing Business As: 3. Mailing Address: City: State: Zip: 4. Contact Person: Years Experience: Contact Person is: □ Owner □ Manager □ Promoter □ Management □ Other: 5. Phone: Fax Number: 6. Web Address: E-Mail Address: 7. Is this a new business? □ Yes □ No If no, how many years have you been in business? 8. Applicant is: □ Individual □ Corporation □ Partnership □ Joint Venture □ Other: 9. Length of season: 10. Who was your last or is your current insurance carrier? 11. What is or was your annual premium? 12. Describe your claims and loss history: 13. Amount of Liability Required: □ 50,000 per accident / 100,000 annual □ 100,000 per accident / 200,000 annual aggregate aggregate □ 100,000 per accident / 300,000 annual □ 200,000 per accident / 300,000 annual aggregate aggregate □ 200,000 per accident / 500,000 annual □ 300,000 per accident / 500,000 annual aggregate aggregate □ 300,000 per accident / 300,000 annual □ 500,000 per accident / 500,000 annual aggregate aggregate □ 300,000 per accident / 1,000,000 annual □ 500,000 per accident / 1,000,000 annual aggregate aggregate 14. Self-Insured Retention desired: □ $1,000 □ $2,500 □ $5,000 □ Other: $ B. -

New Orleans Far from Rebuilt

Newspapers try to be help- ful. Read the story on page 3 about how to make a friend. There is a news story on the left and an advice column on the right. What’s the difference? You can find advice columns in The Denver Post. Look in the Play section ( F). New Orleans far from rebuilt New Orleans, LOUISIANA – One failure in leadership at all levels here,” year ago on August 29, 2005, Hurricane said Reed Kroloff, who was leading Katrina slammed into the Gulf Coast. the Bring New Orleans Back group. More than 1,300 people died, and cities President Bush also expressed along the coasts of Louisiana, Mississippi, frustration as the money gets caught and Alabama were left in ruins. in the large wheels of city, state, and New Orleans suffered the most federal government politics. damage in its history, with mile “The money has been appropriated after mile of homes and businesses (set aside); the formula is in place. devastated. Thousands of homes are The whole purpose is intended to get still in shambles. In many areas, there’s money into people’s pockets to help no phone, gas, or cable service. them rebuild. Now it’s time to move The recovery is painfully slow. forward,” said Bush. The U.S. government appropriated Priscilla McKenzie, 58, escaped (set aside) $110 billion to rebuild the from New Orleans with her daughter. city, yet only about half of the money She is happily settled in Alabama but has actually been sent. Blame for the worries about her friends back home. -

Super Novas 2019 – 2020 Registration Packet

Super Novas 2019 – 2020 Registration Packet Overview of Circus Center’s Pre-Professional Youth Program Circus Center’s Pre-Professional Youth Program is a yearlong training program. Students are asked to commit to the entire year. The program is open to students ages 7–18 (exceptions for skilled younger students may be made). Students build a solid foundation in the basic skills of circus, including strength, flexibility, balance and coordination. Our Pre- Professional Youth Program has three levels: Rising Stars, Super Novas, and the San Francisco Youth Circus. For those students who want it and work for it, Circus Center’s Pre-Professional Youth Program has a long history of preparing young people for elite training and careers in the circus. Even for students who do not pursue a career in the circus, the exposure to high-level training builds discipline, commitment, and confidence that will serve them well in any path they choose. Super Novas (ages 9-16) – Students deepen their circus training when they advance to Super Novas. They continue to develop their strength, flexibility, and coordination while advancing their circus skills. Super Novas focus on two specialties throughout the year which are chosen by the students with coach approval. All Super Novas continue to train tumbling, group acrobatics, and juggling as well. The Super Novas develop their performance skills through weekly dance and acting classes. ● Students are required to complete 80 hours of training over the summer to prepare for the school year ● From September-May,