Path to the 2020 Prosperity Agenda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

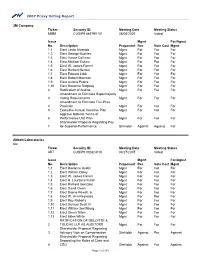

2007 Proxy Voting Report 3M Company Ticker Security ID: MMM

2007 Proxy Voting Report 3M Company Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status MMM CUSIP9 88579Y101 05/08/2007 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No. Description Proponent Rec Vote Cast Mgmt 1.1 Elect Linda Alvarado Mgmt For For For 1.2 Elect George Buckley Mgmt For For For 1.3 Elect Vance Coffman Mgmt For For For 1.4 Elect Michael Eskew Mgmt For For For 1.5 Elect W. James Farrell Mgmt For For For 1.6 Elect Herbert Henkel Mgmt For For For 1.7 Elect Edward Liddy Mgmt For For For 1.8 Elect Robert Morrison Mgmt For For For 1.9 Elect Aulana Peters Mgmt For For For 1.10 Elect Rozanne Ridgway Mgmt For For For 2 Ratification of Auditor Mgmt For For For Amendment to Eliminate Supermajority 3 Voting Requirements Mgmt For For For Amendment to Eliminate Fair-Price 4 Provision Mgmt For For For 5 Executive Annual Incentive Plan Mgmt For For For Approve Material Terms of 6 Performance Unit Plan Mgmt For For For Shareholder Proposal Regarding Pay- 7 for-Superior-Performance ShrHoldr Against Against For Abbott Laboratories Inc Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status ABT CUSIP9 002824100 04/27/2007 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No. Description Proponent Rec Vote Cast Mgmt 1.1 Elect Roxanne Austin Mgmt For For For 1.2 Elect William Daley Mgmt For For For 1.3 Elect W. James Farrell Mgmt For For For 1.4 Elect H. Laurance Fuller Mgmt For For For 1.5 Elect Richard Gonzalez Mgmt For For For 1.6 Elect David Owen Mgmt For For For 1.7 Elect Boone Powell, Jr. -

Bloomberg) -- Sun Microsystems Inc.'S New Chief Executive Officer, Jonathan Schwartz, Pledged to Revive Sales Growth and Reverse Five Years of Market-Share Losses

Print Sun Micro's New Chief Schwartz Pledges to Revive Sales Growth April 25 (Bloomberg) -- Sun Microsystems Inc.'s new chief executive officer, Jonathan Schwartz, pledged to revive sales growth and reverse five years of market-share losses. Schwartz, who was named yesterday to replace Scott McNealy as CEO, said he will review spending over the next 90 days and that he doesn't plan to cut a lot of jobs at the fourth-largest maker of server computers. McNealy will remain chairman. ``We're going to be ramping up the business,'' Schwartz, 40, said yesterday in an interview. ``A lot of what we've focused on over the past four years was recovering the product line.'' Schwartz's pledge echoes that of McNealy, who bought companies to add technologies and to keep Sun's products competitive in the market for servers, the computers used to run Web sites and corporate networks. While McNealy's strategy boosted sales, it failed to stem losses that totaled $4.51 billion over four years. Sun is also falling behind rivals Hewlett-Packard Co. and Dell Inc. Shares of Sun gained 44 cents, or 8.8 percent, to $5.42 in extended trading yesterday after the change was announced. They added 5 cents to $4.98 in regular Nasdaq Stock Market composite trading and have risen 19 percent this year. Schwartz's remarks about status quo may not satisfy some analysts and investors looking for quicker improvement. ``I feel there's a change under way at Sun, I just wish it would happen faster,'' said Brent Bracelin, an analyst at Pacific Crest Securities in Portland, Oregon. -

Case Studies on Innovation

I N N O V A A T I O N 1 www.ibscdc.org ITC’s E-Choupal: A Mirage of the American studios declared in May 2007 Immelt charted his own leadership style Poor? that it had obtained the rights for and brought about a cultural revolution in developing a theme park based on the GE. Expectations were high and the E-Choupal is a novel initiative of ITC extremely successful character of the challenges were many. Immelt had to face Limited (ITC), an Indian conglomerate, popular culture Harry Potter in US, UK several challenges. He had to provide to improve its marketing channel in and all over the world. Walt Disney parks leadership and lend vision to a large, diverse agriculture. It has its roots in Project and resorts have also tried to get the rights conglomerate like GE in the post 9/11 Symphony – a pilot project launched in for Harry Potter theme park but failed to volatile global business scenario. He also 1999 to organise ITC’s agri business. The strike a deal with the creator of the Harry had to shift the company’s focus towards business model was designed to Potter character, J.K. Rowling. Universal innovation and customer centricity in accommodate farmers, intermediaries in and Disney have been competing in the addition to posting continued growth in a the traditional model and the company entertainment industry for many years, and sluggish economy. The case study discusses through information technology. The main Walt Disney had been a leader in theme Immelt’s innovation and customer centric objective of e-Choupal is dissemination and parks. -

STB Developmental Bridge: Improve STEMM University CARED Outcomes (Grades 7-14)

Journal of Instructional Pedagogies Volume 25 STB developmental Bridge: improve STEMM University CARED Outcomes (Grades 7-14) Dr. John H. George, PE ABSTRACT The author was an engineer for 20 years in both development and applications followed by 15 years as adult educator primarily at a Midwestern urban university with under-represented students. Beginning fall 2008 and for the next 7 years, he developed interventions for “under- prepared” STEMM (STEM and pre-Medical) students. This freshmen group entered with ACT math scores ranging from 14 to 21. By: Shaping cooperative peer learning, Teaching problem solving, and Building self-regulated learning; these under-prepared, often under-represented students overcame fundamental future achievement obstacles (i.e., calculus and core (major) coursework sequences). Projected improvement per regression discontinuity for a student at point of discontinuity (21.5 ACT math score) participating or denied treatment is + 30% (+ 0.6 GPA) in follow-up Calculus sequence and + 20% (+ 0.4 GPA) in majority of core coursework. STB program improvements for a 50% rate of participation: Completion: + 15%; Achievement (average): + 23%; Retention: + 21%; Enrollment: + 15%; and (Identity) Diversity: + 4.4%. Keywords: cooperative peer learning, problem solving, self-regulated learning, student completion, student achievement, student retention, student enrollment, student diversity Copyright statement: Authors retain the copyright to the manuscripts published in AABRI journals. Please see the AABRI Copyright Policy at http://www.aabri.com/copyright.html STB developmental Bridge, Page 1 Journal of Instructional Pedagogies Volume 25 PREAMBLE: A CALL TO EDUCATIONAL ACTION “Growth comes through analogy; through seeing how things connect, rather than only seeing how they might be different.” (Albert Einstein) Teachers (educators) grades 5 through doctoral studies possess precisely the same 3 controls over those they lead as do CEOs of multi-national corporations and Brigadier Generals of the Armed Services. -

New Sun CEO Is Unconventional, Controversial

New Sun CEO Is Unconventional, Controversial Don Clark and Christopher Lawton. Wall Street Journal. (Eastern edition). New York, N.Y.: Apr 26, 2006. pg. B.1 WHEN DIRECTORS at Hewlett-Packard Co. saw a need for a new chief executive officer, they recruited Mark Hurd, a button-down operations specialist from NCR Corp. who is now overhauling H-P's sales strategy. Rival Sun Microsystems Inc., by contrast, promoted a brainy insider who promises to stay the computer maker's maverick course. Sun's choice prompts this question: Does Jonathan Schwartz, who succeeds co-founder Scott McNealy as Sun CEO this week, have the management chops to revive a Silicon Valley giant? Mr. McNealy answers with a resounding yes, citing a series of smart decisions by Mr. Schwartz and 10 years of seasoning in various jobs at Sun. "Nobody has any doubts about his strategic vision and capability," says Mr. McNealy, who remains chairman and played a leading role in grooming his successor. On Wall Street, though, some doubts remain. That is partly because Mr. Schwartz says he plans to resist analysts' calls for dramatic job cuts at the company, a one- time high-flyer that is losing money and seeking more growth in sales of its server systems. "It is unclear if CEO Schwartz will be able to provide as an objective and fresh a perspective as might be needed," said Toni Sacconaghi, an analyst at Bernstein Research, in a research note following the Schwartz appointment Tuesday. Mr. Schwartz's operating record is "relatively unproven," and his thinking "eerily similar" to McNealy's, the analyst wrote. -

PLEASE DELIVER TO: Published by Access Intelligence, LLC, Tel: 301-354-2101

URGENT! PLEASE DELIVER TO: www.cablefax.com, Published by Access Intelligence, LLC, Tel: 301-354-2101 5 Pages Today Monday — August 27, 2007 Volume 18 / No. 166 Pretexting Challenge: NCTA Appeals FCC Order on Opt-Ins NCTA has filed an appeal in federal court over an FCC pretexting order released earlier this year. Once again, the association is taking issue with like services being treated dissimilarly. The cable group is challenging the FCC’s Mar decision to require telecommunications carriers and providers of interconnected VoIP services to obtain “opt in” customer approval before disclosing customer proprietary network information to joint venture partners and independent contractors. NCTA told the US Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit earlier this month that the rule is arbitrary and capricious, and violates the 1st Amendment. NCTA sees the problem like this: Verizon can share info with Verizon Wireless because it’s a part owner in the wireless jv with Vodafone. AT&T can share info with AT&T Wireless (formerly Cingular) because it’s an AT&T subsidiary. But cable companies are unable to share info with key jv partner Sprint unless customers opt in. The FCC said it doesn’t comment on litigation. The agency originally adopted the opt-in requirement in an order strengthening privacy rules for phone and wireless carriers. NCTA said it doesn’t object to any other provisions of the order, which includes rules prohibiting the release of a customer’s phone records unless the customer provides a password. This is the 2nd federal appeal of an FCC order that NCTA has filed this year. -

Casos De Éxito En ESTRATEGIA

www.FreeLibros.me Maq.EstrategiaPreliminares.indd ii 4/18/07 11:05:19 PM www.FreeLibros.me Casos de éxito en ESTRATEGIA Maq.EstrategiaPreliminares.indd i 4/18/07 11:05:18 PM www.FreeLibros.me Maq.EstrategiaPreliminares.indd ii 4/18/07 11:05:19 PM www.FreeLibros.me Casos de éxito en ESTRATEGIA Traducción María Eugenia Antúnez Farrugia Maestra en administración de empresas MÉXICO • BOGOTÁ • BUENOS AIRES • CARACAS • GUATEMALA • LISBOA MADRID • NUEVA YORK • SAN JUAN • SANTIAGO SAO PAULO • AUCKLAND • LONDRES • MILÁN • MONTREAL NUEVA DELHI • SAN FRANCISCO • SINGAPUR • ST. LOUIS • SIDNEY • TORONTO estrategia Maq.EstrategiaPreliminares.indd iii 4/18/07 11:05:19 PM www.FreeLibros.me Director Editorial: Fernando Castellanos Rodríguez Editor de desarrollo: Cristina Tapia Montes de Oca Supervisora de producción: Jacqueline Brieno Álvarez Diagramación: Ediciones y Recursos Tecnológicos, S. A. de C. V. CASOS DE ÉXITO EN ESTRATEGIA Prohibida la reproducción total o parcial de esta obra, por cualquier medio, sin autorización escrita del editor. DERECHOS RESERVADOS © 2007, respecto a la primera edición en español por, McGRAW-HILL INTERAMERICANA EDITORES, S.A. de C. V. A subsidiary of the McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Corporativo Punta Santa Fe Prolongación Paseo de la Reforma 1015, Torre A, Piso 17, Col. Desarrollo Santa Fe, Delegación Álvaro Obregón C. P. 01376, México, D. F. Miembro de la Cámara Nacional de la Industria Editorial Mexicana Reg. Núm. 736 ISBN 13: 978-970-10-6267-8 ISBN 10: 970-10-6267-1 1234567890 0986543217 Impreso en México Printed in Mexico Translated from the 1st English edition of Leadership power plays By: BusinessWeek Copyright © MMVII by McGraw Hill Companies, Inc. -

Motorola's Spin-Off of Its Cell Phone Business

For the exclusive use of P. Sun, 2017. ID# CU129 PUBLISHED ON FEBRUARY 23, 2012 Motorola’s Spin-Off of Its Cell Phone Business BY KATHRYN RUDIE HARRIGAN* Introduction In March 2008, Motorola, Inc. announced that it would split itself into two publicly traded companies by spinning off its unprofitable mobile devices handset unit in a tax-free distribution to its shareholders. The spin-off was, in fact, postponed until January 4, 2011, as Motorola prepared for this momentous strategy change. The core of Motorola was renamed Motorola Solutions, Inc. (MSI) while the divested cell phone company was called Motorola Mobility, Inc. (MMI). At the time of its announcement, the cell phone business was the largest division of Motorola (52% of its sales), with $18.9 billion in net sales in year ending December 31, 2007, (a 33% decline from year ending December 31, 2006) and a loss of $1.2 billion (see Exhibit 1). Motorola’s money-losing and notoriously volatile phone business was in such bad shape that the unit attracted doubts about whether it could survive on its own.1 The other Motorola businesses were profitable (including Motorola’s enterprise solutions and public safety units, as well as its telecommunications infrastructure and cable set-top receiver equipment businesses). Unfortunately, neither of the company’s two profitable divisions—the home and networks mobility segment nor the enterprise mobility solutions segment—enjoyed the growth prospects that excited Motorola’s investors the way its cell phone business did. TABLE 1. MOTOROLA, INC. NET SALES. Year Ended December 31 (Dollars in millions) 2008 2007 2006 Mobile Devices $12,099 $18,988 $28,383 Home & Networks Mobility $10,086 $10,014 $9,164 Enterprise Mobility Solutions $8,093 $7,729 $5,400 Author affiliation Copyright information *Henry R. -

In Re Portal Software, Inc. Securities Litigation 03-CV-5138

Case 3:03-cv-05138-VRW Document 145 Filed 02/08/2006 Page 1 of 5 1 LERACH COUGHLIN STOIA GELLER RUDMAN & ROBBINS LLP 2 SANFORD SVETCOV (36561) 100 Pine Street, Suite 2600 3 San Francisco, CA 94111 Telephone: 415/288-4545 4 415/288-4534 (fax) [email protected] 5 – and – SAMUEL H. RUDMAN 6 ROBERT M. ROTHMAN (Pro Hac Vice) RUSSELL J. GUNYAN 7 58 South Service Road, Suite 200 Melville, NY 11747 8 Telephone: 631/367-7100 631/367-1173 (fax) 9 [email protected] [email protected] 10 [email protected] 11 Lead Counsel for Plaintiff and the Class 12 GREEN WELLING LLP ROBERT S. GREEN (136183) 13 235 Pine Street, 15th Floor San Francisco, CA 94104 14 Telephone: 415/477-6700 415/477-6710 (fax) 15 Liaison Counsel for Plaintiff and the Class 16 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 17 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 18 In re PORTAL SOFTWARE, INC. ) Master File No. C-03-5138-VRW 19 SECURITIES LITIGATION ) ) CLASS ACTION 20 ) This Document Relates To: ) DECLARATION OF SANFORD SVETCOV 21 ) IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS’ ALL ACTIONS. ) OPPOSITION TO DEFENDANTS’ MOTION 22 ) TO DISMISS FOURTH CONSOLIDATED ) AMENDED COMPLAINT 23 DATE: March 23, 2006 24 TIME: 2:00 p.m. COURTROOM: 6, Hon. Vaughn R. Walker 25 26 27 28 Case 3:03-cv-05138-VRW Document 145 Filed 02/08/2006 Page 2 of 5 1 I, Sanford Svetcov, declare as follows: 2 I am a partner in the Lerach Coughlin Stoia Geller Rudman & Robbins LLP law firm, lead 3 counsel for plaintiffs and the class in this action. -

United States District Court Findings of Fact and Conclusions Of

Case 5:17-cv-00220-LHK Document 1490 Filed 05/21/19 Page 1 of 233 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 9 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 10 SAN JOSE DIVISION 11 12 FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION, Case No. 17-CV-00220-LHK 13 Plaintiff, FINDINGS OF FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW 14 v. 15 QUALCOMM INCORPORATED, 16 Defendant. 17 United States District Court District United States Northern District of California District Northern 18 Plaintiff Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”) brings suit against Defendant Qualcomm 19 Incorporated (“Qualcomm”) for allegedly violating Section 5(a) of the FTC Act, 15 U.S.C. § 20 45(a), and seeks permanent injunctive relief. Specifically, the FTC claims that Qualcomm has 21 harmed competition in two markets for baseband processors, also called modem chips, through a 22 set of interrelated Qualcomm practices. The FTC Act prohibits “[u]nfair methods of competition,” 23 which include violations of the Sherman Act. The FTC asserts that Qualcomm’s conduct violates 24 (1) Section 1 of the Sherman Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1; (2) Section 2 of the Sherman Act, 15 U.S.C. § 2; 25 and (3) Section 5 of the FTC Act, 15 U.S.C. § 45(a). ECF No. 966. 26 On April 3, 2017, Qualcomm moved to dismiss the FTC’s Complaint. ECF No. 69. On 27 June 26, 2017, the Court denied Qualcomm’s motion to dismiss. ECF No. 134. 28 1 Case No. 17-CV-00220-LHK FINDINGS OF FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW Case 5:17-cv-00220-LHK Document 1490 Filed 05/21/19 Page 2 of 233 1 On August 30, 2018, the FTC moved for partial summary judgment on the question of 2 whether Qualcomm’s commitments to two standard setting organizations (“SSOs”), the Alliance 3 for Telecommunications Industry Solutions (“ATIS”) and the Telecommunications Industry 4 Association (“TIA”), require Qualcomm to license to other modem chip suppliers on fair, 5 reasonable, and nondiscriminatory terms Qualcomm’s patents that are essential to practicing the 6 ATIS and TIA standards. -

Schedule 14A

Use these links to rapidly review the document TABLE OF CONTENTS PROXY STATEMENT FOR 2016 ANNUAL MEETING OF STOCKHOLDERS Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 SCHEDULE 14A Proxy Statement Pursuant to Section 14(a) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (Amendment No. ) Filed by the Registrant ý Filed by a Party other than the Registrant o Check the appropriate box: o Preliminary Proxy Statement o Confidential, for Use of the Commission Only (as permitted by Rule 14a-6(e)(2)) ý Definitive Proxy Statement o Definitive Additional Materials o Soliciting Material under §240.14a-12 NETSUITE INC. (Name of Registrant as Specified In Its Charter) (Name of Person(s) Filing Proxy Statement, if other than the Registrant) Payment of Filing Fee (Check the appropriate box): ý No fee required. o Fee computed on table below per Exchange Act Rules 14a-6(i)(1) and 0-11. (1) Title of each class of securities to which transaction applies: (2) Aggregate number of securities to which transaction applies: (3) Per unit price or other underlying value of transaction computed pursuant to Exchange Act Rule 0-11 (set forth the amount on which the filing fee is calculated and state how it was determined): (4) Proposed maximum aggregate value of transaction: (5) Total fee paid: o Fee paid previously with preliminary materials. o Check box if any part of the fee is offset as provided by Exchange Act Rule 0-11(a)(2) and identify the filing for which the offsetting fee was paid previously. -

2012 Proxy Voting Report 3M Co. Ticker Security ID: MMM CUSIP

2012 Proxy Voting Report 3M Co. Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status MMM CUSIP 88579Y101 05/08/2012 Voted Meeting Type Country of Trade Annual United States Issue No. Description Proponent Mgmt Rec Vote Cast For/Agnst Mgmt 1 Elect Linda Alvarado Mgmt For For For 2 Elect Vance Coffman Mgmt For For For 3 Elect Michael Eskew Mgmt For For For 4 Elect W. James Farrell Mgmt For For For 5 Elect Herbert Henkel Mgmt For For For 6 Elect Edward Liddy Mgmt For For For 7 Elect Robert Morrison Mgmt For For For 8 Elect Aulana Peters Mgmt For Against Against 9 Elect Inge Thulin Mgmt For For For 10 Elect Robert Ulrich Mgmt For For For 11 Ratification of Auditor Mgmt For For For 12 Advisory Vote on Executive Mgmt For For For Compensation 13 Amendment to the General Mgmt For For For Employees Stock Purchase Plan 14 Amendment to the 2008 Long- Mgmt For For For Term Incentive Plan 15 Shareholder Proposal Regarding ShrHldr Against For Against Lobbying Report 16 Shareholder Proposal Regarding ShrHldr Against Against For Prohibition on Political Spending 17 Shareholder Proposal Regarding ShrHldr Against For Against Independent Board Chair Abbott Laboratories Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status ABT CUSIP 002824100 04/27/2012 Voted Meeting Type Country of Trade Annual United States Issue No. Description Proponent Mgmt Rec Vote Cast For/Agnst Mgmt 1.1 Elect Robert Alpern Mgmt For For For 1.2 Elect Roxanne Austin Mgmt For For For 1.3 Elect Sally Blount Mgmt For For For 1.4 Elect W.