Media Integrity Matters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TV and On-Demand Audiovisual Services in Albania Table of Contents

TV and on-demand audiovisual services in Albania Table of Contents Description of the audiovisual market.......................................................................................... 2 Licensing authorities / Registers...................................................................................................2 Population and household equipment.......................................................................................... 2 TV channels available in the country........................................................................................... 3 TV channels established in the country..................................................................................... 10 On-demand audiovisual services available in the country......................................................... 14 On-demand audiovisual services established in the country..................................................... 15 Operators (all types of companies)............................................................................................ 15 Description of the audiovisual market The Albanian public service broadcaster, RTSH, operates a range of channels: TVSH (Shqiptar TV1) TVSH 2 (Shqiptar TV2) and TVSH Sat; and in addition a HD channel RTSH HD, and three thematic channels on music, sport and art. There are two major private operators, TV Klan and Top Channel (Top Media Group). The activity of private electronic media began without a legal framework in 1995, with the launch of the unlicensed channel Shijak TV. After -

Stream Name Category Name Coronavirus (COVID-19) |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---TNT-SAT ---|EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 SD |EU|

stream_name category_name Coronavirus (COVID-19) |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---------- TNT-SAT ---------- |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 FULL HD 1 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 FHD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT PARIS PREMIERE |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT PARIS PREMIERE FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC 1 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ARTE SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ARTE FR |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT RMC STORY |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT RMC STORY SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---------- Information ---------- |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TV5 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TV5 MONDE FBS HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT France 24 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE INFO SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE INFO HD -

Media Integrity Matters

a lbania M edia integrity Matters reClaiMing publiC serviCe values in Media and journalisM This book is an Media attempt to address obstacles to a democratic development of media systems in the countries of South East Europe by mapping patterns of corrupt relations and prac bosnia and Herzegovina tices in media policy development, media ownership and financing, public service broadcasting, and journalism as a profession. It introduces the concept of media in tegrity to denote public service values in media and journalism. Five countries were integrity covered by the research presented in this book: Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia / MaCedonia / serbia Croatia, Macedonia and Serbia. The research – conducted between July 2013 and February 2014 – was part of the regional project South East European Media Obser vatory – Building Capacities and Coalitions for Monitoring Media Integrity and Ad vancing Media Reforms, coordinated by the Peace Institute in Ljubljana. Matters reClaiMing publiC serviCe values in Media and journalisM Media integrity M a tters ISBN 978-961-6455-70-0 9 7 8 9 6 1 6 4 5 5 7 0 0 ovitek.indd 1 3.6.2014 8:50:48 ALBANIA MEDIA INTEGRITY MATTERS RECLAIMING PUBLIC SERVICE VALUES IN MEDIA AND JOURNALISM Th is book is an attempt to address obstacles to a democratic development of media systems in the MEDIA countries of South East Europe by mapping patterns of corrupt relations and prac- BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA tices in media policy development, media ownership and fi nancing, public service broadcasting, and journalism as a profession. It introduces the concept of media in- tegrity to denote public service values in media and journalism. -

People's Advocate… ………… … 291

REPUBLIC OF ALBANIA PEOPLE’S ADVOCATE ANNUAL REPORT On the activity of the People’s Advocate 1st January – 31stDecember 2013 Tirana, February 2014 REPUBLIC OF ALBANIA ANNUAL REPORT On the activity of the People’s Advocate 1st January – 31st December 2013 Tirana, February 2014 On the Activity of People’s Advocate ANNUAL REPORT 2013 Honorable Mr. Speaker of the Assembly of the Republic of Albania, Honorable Members of the Assembly, Ne mbeshtetje te nenit 63, paragrafi 1 i Kushtetutes se republikes se Shqiperise dhe nenit26 te Ligjit N0.8454, te Avokatit te Popullit, date 04.02.1999 i ndryshuar me ligjin Nr. 8600, date10.04.200 dhe Ligjit nr. 9398, date 12.05.2005, Kam nderin qe ne emer te Institucionit te Avokatit te Popullit, tj’u paraqes Raportin per veprimtarine e Avokatit te Popullit gjate vitit 2013. Pursuant “ to Article 63, paragraph 1 of the Constitution of the Republic of Albania and Article 26 of Law No. 8454, dated 04.02.1999 “On People’s Advocate”, as amended by Law No. 8600, dated 10.04.2000 and Law No. 9398, dated 12.05.2005, I have the honor, on behalf of the People's Advocate Institution, to submit this report on the activity of People's Advocate for 2013. On the Activity of People’s Advocate Sincerely, PEOPLE’S ADVOCATE Igli TOTOZANI ANNUAL REPORT 2013 Table of Content Prezantim i Raportit Vjetor 2013 8 kreu I: 1Opinione dhe rekomandime mbi situaten e te drejtave te njeriut ne Shqiperi …9 2) permbledhje e Raporteve te vecanta drejtuar Parlamentit te Republikes se Shqiperise......................... -

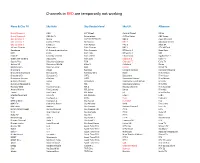

Channels in RED Are Temporarily Not Working

Channels in RED are temporarily not working Nova & Ote TV Sky Italy Sky Deutschland Sky UK Albanian Nova Cinema 1 AXN 13th Street Animal Planet 3 Plus Nova Cinema 2 AXN SciFi Boomerang At The Races ABC News Ote Cinema 1 Boing Cartoon Network BBC 1 Agon Channel Ote Cinema 2 Caccia e Pesca Discovery BBC 2 Albanian screen Ote Cinema 3 Canale 5 Film Action BBC 3 Alsat M Village Cinema Cartoonito Film Cinema BBC 4 ATV HDTurk Sundance CI Crime Investigation Film Comedy BT Sports 1 Bang Bang FOX Cielo Film Hits BT Sports 2 BBF FOXlife Comedy Central Film Select CBS Drama Big Brother 1 Greek VIP Cinema Discovery Film Star Channel 5 Club TV Sports Plus Discovery Science FOX Chelsea FC Cufo TV Action 24 Discovery World Kabel 1 Clubland Doma Motorvision Disney Junior Kika Colors Elrodi TV Discovery Dmax Nat Geo Comedy Central Explorer Shkence Discovery Showcase Eurosport 1 Nat Geo Wild Dave Film Aktion Discovery ID Eurosport 2 ORF1 Discovery Film Autor Discovery Science eXplora ORF2 Discovery History Film Drame History Channel Focus ProSieben Discovery Investigation Film Dy National Geographic Fox RTL Discovery Science Film Hits NatGeo Wild Fox Animation RTL 2 Disney Channel Film Komedi Animal Planet Fox Comedy RTL Crime Dmax Film Nje Travel Fox Crime RTL Nitro E4 Film Thriller E! Entertainment Fox Life RTL Passion Film 4 Folk+ TLC Fox Sport 1 SAT 1 Five Folklorit MTV Greece Fox Sport 2 Sky Action Five USA Fox MAD TV Gambero Rosso Sky Atlantic Gold Fox Crime MAD Hits History Sky Cinema History Channel Fox Life NOVA MAD Greekz Horror Channel Sky -

SYRIZA VICTORY in GREEK PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS, JANUARY 2015: Perceptions of Western Balkan Media & Opinion Makers

SYRIZA VICTORY IN GREEK PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS, JANUARY 2015: Perceptions of Western Balkan Media & Opinion Makers Maja Maksimović Bledar Feta Katherine Poseidon Ioannis Armakolas Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy (ELIAMEP) South-East Europe Programme Athens 2015 SYRIZA VICTORY IN GREEK PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS, JANUARY 2015: Perceptions of Western Balkan Media & Opinion Makers Contents About the Authors .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 About the South-East Europe Programme .............................................................................................................. 5 Preface .................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Executive Summary........................................................................................................................................................... 7 PART I - The January 2015 Parliamentary Elections in Greece: Perceptions of Western Balkan Media .................................................................................................................................................................................... 12 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................ -

Albania Democratic Economic Governance

Fall 08 FINAL NARRATIVE REPORT Thematic window Albania Democratic Economic Governance Joint Programme Title: Economic governance, regulatory reform, public participation, and pro -poor development in Albania January 2013 Prologue The MDG Achievement Fund was established in 2007 through a landmark agreement signed between the Government of Spain and the UN system. With a total contribution of approximately USD 900 million, the MDG-Fund has financed 130 joint programmes in eight Thematic Windows, in 50 countries around the world. The joint programme final narrative report is prepared by the joint programme team. It reflects the final programme review conducted by the Programme Management Committee and National Steering Committee to assess results against expected outcomes and outputs. The report is divided into five (5) sections. Section I provides a brief introduction on the socio economic context and the development problems addressed by the joint programme, and lists the joint programme outcomes and associated outputs. Section II is an assessment of the joint programme results. Section III collects good practices and lessons learned. Section IV covers the financial status of the joint programme; and Section V is for other comments and/or additional information. We thank our national partners and the United Nations Country Team, as well as the joint programme team for their efforts in undertaking this final narrative report. MDG-F Secretariat FINAL MDG-F JOINT PROGRAMME NARRATIVE REPORT Participating UN Organization(s) Sector(s)/Area(s)/Theme(s) UNDP- Lead agency Albania – Democratic Economic Governance World Bank Joint Programme Title Joint Programme Number Economic Governance, Regulatory Reform and Project ID: 00072331 Pro-Poor Development in Albania Joint Programme Cost Joint Programme [Location] [Sharing - if applicable] [Fund Contribution): USD 2,097,200 Region(s): Albania Govt. -

Albanian Media Institute, “Children and the Media: a Survey of the Children and Young People’S Opinion on Their Use and Trust in Media,” December 2011, P

COUNTRY REPORT MAPPING DIGITAL MEDIA: ALBANIA Mapping Digital Media: Albania A REPORT BY THE OPEN SOCIETY FOUNDATIONS WRITTEN BY Ilda Londo (reporter) EDITED BY Marius Dragomir and Mark Thompson (Open Society Media Program editors) EDITORIAL COMMISSION Yuen-Ying Chan, Christian S. Nissen, Dusˇan Reljic´, Russell Southwood, Michael Starks, Damian Tambini The Editorial Commission is an advisory body. Its members are not responsible for the information or assessments contained in the Mapping Digital Media texts OPEN SOCIETY MEDIA PROGRAM TEAM Meijinder Kaur, program assistant; Morris Lipson, senior legal advisor; and Gordana Jankovic, director OPEN SOCIETY INFORMATION PROGRAM TEAM Vera Franz, senior program manager; Darius Cuplinskas, director 20 January 2012 Contents Mapping Digital Media ..................................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................... 6 Context ............................................................................................................................................. 9 Social Indicators ................................................................................................................................ 11 Economic Indicators ......................................................................................................................... 12 1. Media Consumption: Th e Digital Factor ......................................................................... -

ALBANIA Ilda Londo

ALBANIA Ilda Londo porocilo.indb 51 20.5.2014 9:04:36 INTRODUCTION Policies on media development have ranged from over-regulation to complete liberali- sation. Media legislation has changed frequently, mainly in response to the developments and emergence of media actors on the ground, rather than as a result of a deliberate and carefully thought-out vision and strategy. Th e implementation of the legislation was ham- pered by political struggles, weak rule of law and interplays of various interests, but some- times the reason was the incompetence of the regulatory bodies themselves. Th e Albanian media market is small, but the media landscape is thriving, with high number of media outlets surviving. Th e media market suff ers from severe lack of trans- parency. It also seems that diversifi cation of sources of revenues is not satisfactory. Media are increasingly dependent on corporate advertising, on the funds arising from other busi- nesses of their owners, and to some extent, on state advertising. In this context, the price of survival is a loss of independence and direct or indirect infl uence on media content. Th e lack of transparency in media ratings, advertising practices, and business practices in gen- eral seems to facilitate even more the infl uences on media content exerted by other actors. In this context, the chances of achieving quality and public-oriented journalism are slim. Th e absence of a strong public broadcaster does not help either. Th is research report will seek to analyze the main aspects of the media system and the way they aff ect media integrity. -

Njoftimi-Media-Data-07.06.2017.Pdf

NJOFTIM PËR MEDIA Ditën e mërkurë, në datën 07 qershor 2017, u zhvillua mbledhja e radhës së Autoritetit të Page | 1 Mediave Audiovizive (AMA), ku morën pjesë anëtarët e mëposhtëm: Gentian SALA Kryetar Sami NEZAJ Zëvendëskryetar Agron GJEKMARKAJ Anëtar Gledis GJIPALI Anëtar Piro MISHA Anëtar Suela MUSTA Anëtar Zylyftar BREGU Anëtar AMA, pasi mori në shqyrtim çështjet e rendit të ditës, vendosi: 1. Miratimin e Numrit Logjik të Programit të shërbimeve programore kombëtare të përgjithshme dhe shërbimeve programore private rajonale/lokale, sipas listës bashkëlidhur. (Vendimi nr. 98, datë 07.06.2017); 2. Miratimin e rregullores “Për procedurat dhe kriteret e dhënies së autorizimeve”. (Vendimi nr. 99, datë 07.06.2017); 3. Miratimin e rregullores “Për procedurat dhe kriteret për dhënien e licencës lokale të transmetimit audioviziv në periudhën tranzitore”. (Vendimi nr. 100, datë 07.06.2017); 4. Miratimin e Rregullores “Për procedurat e inspektimit të veprimtarisë audiovizive të ofruesve të shërbimit mediatik audio dhe/ose audioviziv”. (Vendimi nr. 101, datë 07.06.2017); Po ashtu, AMA pasi shqyrtoi projekt-rregulloren “Mbi procedurat për shqyrtimin e ankesave nga Këshilli Ankesave dhe të drejtën e përgjigjes”, kërkoi rishikimin e tekstit të saj. Rruga “Papa Gjon Pali i II”, Tiranë |ëëë.ama.gov.al Tel. +355 4 2233370 |Email. [email protected] LISTA E NUMRIT LOGJIK TË SHËRBIMEVE PROGRAMORE AUDIOVIZIVE NLP SHËRBIMI PROGRAMOR Page | 2 1 "RTSH 1" 2 "RTSH 2" 3 "RTSH 3" 4 Top-Channel / Klan TV * 5 Klan TV / Top-Channel * 6 "Klan +" 7 "Vizion +" 8 “News -

Media Integrity Matters

a lbania M edia integrity Matters reClaiMing publiC serviCe values in Media and journalisM This book is an Media attempt to address obstacles to a democratic development of media systems in the countries of South East Europe by mapping patterns of corrupt relations and prac bosnia and Herzegovina tices in media policy development, media ownership and financing, public service broadcasting, and journalism as a profession. It introduces the concept of media in tegrity to denote public service values in media and journalism. Five countries were integrity covered by the research presented in this book: Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia / MaCedonia / serbia Croatia, Macedonia and Serbia. The research – conducted between July 2013 and February 2014 – was part of the regional project South East European Media Obser vatory – Building Capacities and Coalitions for Monitoring Media Integrity and Ad vancing Media Reforms, coordinated by the Peace Institute in Ljubljana. Matters reClaiMing publiC serviCe values in Media and journalisM Media integrity M a tters ISBN 978-961-6455-70-0 9 7 8 9 6 1 6 4 5 5 7 0 0 ovitek.indd 1 3.6.2014 8:50:48 ALBANIA MEDIA INTEGRITY MATTERS RECLAIMING PUBLIC SERVICE VALUES IN MEDIA AND JOURNALISM Th is book is an attempt to address obstacles to a democratic development of media systems in the MEDIA countries of South East Europe by mapping patterns of corrupt relations and prac- BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA tices in media policy development, media ownership and fi nancing, public service broadcasting, and journalism as a profession. It introduces the concept of media in- tegrity to denote public service values in media and journalism. -

Achievements Forum-2020 TOP100 Register

Achievements Forum-2020 TOP100 Register www.ebaoxford.co.uk 2020 The crisis transformations in the global economy and the pandemic posed a number of challenges for regional business - from the need for creative solutions in the field of personal safety and HR to the maximum strengthening of brand loyalty and brand recognition, expansion of partnerships and business geography. Today reality not only emphasises the importance of successful regional business for the development of the national economy, but also encourages international cooperation and introduction of innovative technologies and projects. Europe business Assembly continues annual research with the aim to select and encourage promising companies at the forefront of regional business. Following long-term EBA traditions, we are very pleased to present sustainable and promising companies and institutions to the global business community, and express our gratitude to them by presenting special awards. EBA created a special modern online platform to promote our members and award winners, exchange best practices, present achievements, share innovative projects and search for partners and clients. We conducted 3 online events on this platform in 2020. On the pages of this catalogue EBA proudly presents outstanding companies and personalities. They have all demonstrated remarkable resilience in a year of unprecedented challenges. We congratulate awardees and wish them further prosperity, health, happiness, love, family affluence and new business achievements! EBA team BUSINESS CARDS DR.DUDIKOVA CLINIC Ekaterina Dudikova Kiev, Ukraine phone: +38(067)172-53-47 e-mail: [email protected] www.dr-dudikova.clinic Dr.Dudikova Clinic was founded by Ekaterina Dudikova, a dermatologist-surgeon, a master of medicine with 14 years of experience.