View on How Theater

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

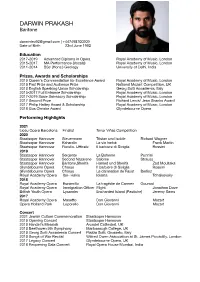

Darwin Prakash CV July 2021

DARWIN PRAKASH Baritone [email protected] | +447498700209 Date of Birth 23rd June 1993 Education 2017-2019 Advanced Diploma in Opera Royal Academy of Music, London 2015-2017 MA Performance (Vocals) Royal Academy of Music, London 2011-2014 BSc (Hons.) Geology University of Delhi, India Prizes, Awards and Scholarships 2019 Queen's Commendation for Excellence Award Royal Academy of Music, London 2019 First Prize and Audience Prize National Mozart Competition, UK 2018 English Speaking Union Scholarship Georg Solti Accademia, Italy 2015-2017 Full Entrance Scholarship Royal Academy of Music, London 2017-2019 Susie Sainsbury Scholarship Royal Academy of Music, London 2017 Second Prize Richard Lewis/ Jean Shanks Award 2017 Philip Hattey Award & Scholarship Royal Academy of Music, London 2016 Gus Christie Award Glyndebourne Opera Performing Highlights 2021 Liceu Opera Barcelona Finalist Tenor Viñas Competition 2020 Staatsoper Hannover Steuermann Tristan und Isolde Richard Wagner Staatsoper Hannover Kaherdin Le vin herbé Frank Martin Staatsoper Hannover Fiorello, Ufficale Il barbiere di Siviglia Rossini 2019 Staatsoper Hannover Sergente La Boheme Puccini Staatsoper Hannover Second Nazarene Salome Strauss Staatsoper Hannover Baritone,Sherifa Hamed und Sherifa Zad Moultaka Glyndebourne Opera Chorus Il barbiere di Siviglia Rossini Glyndebourne Opera Chorus La damnation de Faust Berlioz Royal Academy Opera Ibn- Hakia Iolanta Tchaikovsky 2018 Royal Academy Opera Escamillo La tragédie de Carmen Gounod Royal Academy Opera Immigration Officer Flight Jonathan Dove British Youth Opera Lysander Enchanted Island (Pastiche) Jeremy Sams 2017 Royal Academy Opera Masetto Don Giovanni Mozart Opera Holland Park Leporello Don Giovanni Mozart Concert 2021 Jewish Culture Commemoration Staatsoper Hannover 2019 Opening Concert Staatsoper Hannover 2019 Handel's Messiah Arundel Cathedral, UK 2018 Beethoven 9th Symphony Marlborough College, UK 2018 Georg Solti Accademia Concert Piazza Solti, Grosseto, Italy 2018 Songs of War Recital Wilfred Owen Association at St. -

Advance Program Notes New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players H.M.S

Advance Program Notes New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players H.M.S. Pinafore Friday, May 5, 2017, 7:30 PM These Advance Program Notes are provided online for our patrons who like to read about performances ahead of time. Printed programs will be provided to patrons at the performances. Programs are subject to change. Albert Bergeret, artistic director in H.M.S. Pinafore or The Lass that Loved a Sailor Libretto by Sir William S. Gilbert | Music by Sir Arthur Sullivan First performed at the Opera Comique, London, on May 25, 1878 Directed and conducted by Albert Bergeret Choreography by Bill Fabis Scenic design by Albère | Costume design by Gail Wofford Lighting design by Benjamin Weill Production Stage Manager: Emily C. Rolston* Assistant Stage Manager: Annette Dieli DRAMATIS PERSONAE The Rt. Hon. Sir Joseph Porter, K.C.B. (First Lord of the Admiralty) James Mills* Captain Corcoran (Commanding H.M.S. Pinafore) David Auxier* Ralph Rackstraw (Able Seaman) Daniel Greenwood* Dick Deadeye (Able Seaman) Louis Dall’Ava* Bill Bobstay (Boatswain’s Mate) David Wannen* Bob Becket (Carpenter’s Mate) Jason Whitfield Josephine (The Captain’s Daughter) Kate Bass* Cousin Hebe Victoria Devany* Little Buttercup (Mrs. Cripps, a Portsmouth Bumboat Woman) Angela Christine Smith* Sergeant of Marines Michael Connolly* ENSEMBLE OF SAILORS, FIRST LORD’S SISTERS, COUSINS, AND AUNTS Brooke Collins*, Michael Galante, Merrill Grant*, Andy Herr*, Sarah Hutchison*, Hannah Kurth*, Lance Olds*, Jennifer Piacenti*, Chris-Ian Sanchez*, Cameron Smith, Sarah Caldwell Smith*, Laura Sudduth*, and Matthew Wages* Scene: Quarterdeck of H.M.S. Pinafore *The actors and stage managers employed in this production are members of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. -

International Richard Wagner Congress – Bonn 23Rd to 27Th September 2020

International Richard Wagner Congress – Bonn 23rd to 27th September 2020 Imprint The Richard Wagner Congress 2020 Richard-Wagner-Verband Bonn e.V. programme Andreas Loesch (Vorsitzender) John Peter (stellv. Vorsitzender) was created in collaboration with Zanderstraße 47, 53177 Bonn Tel. +49-(0)178-8539559 [email protected] Organiser / booking details ARS MUSICA Musik- und Kulturreisen GmbH Bachemer Straße 209, 50935 Köln Tel: +49-(0)221-16 86 53 00 Fax: +49-(0)221-16 86 53 01 [email protected] RICHARD-WAGNER-VERBAND BONN E.V. and is sponsored by Image sources frontpage from left to right, from top to bottom - Richard-Wagner-Verband Bonn - Michael Sondermann/Bundesstadt Bonn - Deutsche Post / Richard-Wagner-Verband Bonn - StadtMuseum Bonn - Michael Sondermann/Bundesstadt Bonn - Beethovenhaus Bonn - Stadt Königswinter - Michael Sondermann/Bundesstadt Bonn - Stadtmuseum Siegburg - Michael Sondermann/Bundesstadt Bonn - Michael Sondermann/Bundesstadt Bonn Current information about the program backpage - Michael Sondermann/Bundesstadt Bonn rwv-bonn.de/kongress-2020 Congress Programme for all Congress days 2 p.m. | Gustav-Stresemann-Institut Dear Members of the Richard Wagner Societies, dear Friends of Richard Wagner’s Music, Conference Hotel Hilton Richard Wagner – en miniature Symposium: »Beethoven, Wagner and the political “Welcome” to the Congress of the International Association of Richard Wagner Societies in 2020, commemorating Ludwig “Der Meister” depicted on stamps movements of their time « (simultaneous translation) van Beethoven’s 250th birthday worldwide. Richard Wagner appreciated him more than any other composer in his life, which Prof. Dr. Dieter Borchmeyer, PD Dr. Ulrike Kienzle, is why the Congress in Bonn, Beethoven’s hometown, is going to centre on “Beethoven and Wagner”. -

Wagner and Bayreuth Mendelssohn-Bartholdy and Berlin Brahms and Detmold

MUSIC DOCUMENTARY 30 MIN. VERSIONS Wagner and Bayreuth Arabic, English, French, German, Portuguese, Spanish (01 x 30 min.) No city in the world is so closely identified with a composer as Bayreuth is with Richard Wag- ner. Towards the end of the 19th century Richard Wagner had a Festival Theatre built here and RIGHTS revived the Ancient Greek idea of annual festivals. Nowadays, these festivals are attended by Worldwide, VOD, Mobile around 60,000 people. ORDER NUMBER 66 3238 VERSIONS Mendelssohn-Bartholdy and Berlin Arabic, English, French, German, Portuguese, Spanish (01 x 30 min.) Felix Mendelssohn, one of the most important composers of the 19th century, was influenced decisively by Berlin, which gave shape to the form and development of his music. The televi- RIGHTS sion documentary traces Mendelssohn’s life in the Berlin of the 19th century, as well as show- Worldwide, VOD, Mobile ing the city today. ORDER NUMBER 66 3305 VERSIONS Brahms and Detmold Arabic, English, French, German, Portuguese, Spanish (01 x 30 min.) Around the middle of the 19th century Detmold, a small town in the west of Germany, was a centre of the sort of cultural activity that would normally be expected only of a large city. An RIGHTS artistically-minded local prince saw to it that famous artists came to Detmold and performed in Worldwide, VOD, Mobile the theatre or at his court. For several years the town was the home of composer Johannes Brahms. Here, as Court Musician, he composed some of his most beautiful vocal and instru- ORDER NUMBER ment works. 66 3237 dw-transtel.com Classics | DW Transtel. -

Il Favore Degli Dei (1690): Meta-Opera and Metamorphoses at the Farnese Court

chapter 4 Il favore degli dei (1690): Meta-Opera and Metamorphoses at the Farnese Court Wendy Heller In 1690, Giovanni Maria Crescimbeni (1663–1728) and Gian Vincenzo Gravina (1664–1718), along with several of their literary colleagues, established the Arcadian Academy in Rome. Railing against the excesses of the day, their aim was to restore good taste and classical restraint to poetry, art, and opera. That same year, a mere 460 kilometres away, the Farnese court in Parma offered an entertainment that seemed designed to flout the precepts of these well- intentioned reformers.1 For the marriage of his son Prince Odoardo Farnese (1666–1693) to Dorothea Sofia of Neuberg (1670–1748), Duke Ranuccio II Farnese (1639–1694) spared no expense, capping off the elaborate festivities with what might well be one of the longest operas ever performed: Il favore degli dei, a ‘drama fantastico musicale’ with music by Bernardo Sabadini (d. 1718) and poetry by the prolific Venetian librettist Aurelio Aureli (d. 1718).2 Although Sabadini’s music does not survive, we are left with a host of para- textual materials to tempt the historical imagination. Aureli’s printed libretto, which includes thirteen engravings, provides a vivid sense of a production 1 The object of Crescimbeni’s most virulent condemnation was Giacinto Andrea Cicognini’s Giasone (1649), set by Francesco Cavalli, which Crescimbeni both praised as a most per- fect drama and condemned for bringing about the downfall of the genre. Mario Giovanni Crescimbeni, La bellezza della volgar poesia spiegata in otto dialoghi (Rome: Buagni, 1700), Dialogo iv, pp. -

Marschner Heinrich

MARSCHNER HEINRICH Compositore tedesco (Zittau, 16 agosto 1795 – Hannover, 16 dicembre 1861) 1 Annoverato fra i maggiori compositori europei della sua epoca, nonché degno rivale in campo operistico di Carl Maria von Weber, strinse amicizia con i maggiori musicisti del tempo, fra cui Ludwig van Beethoven e Felix Mendelssohn Bartoldy. Dopo gli studi fatti a Lipsia ed a Praga con Tomášek e dopo essersi introdotto nel mondo musicale viennese, fu nominato maestro di cappella a Bratislava e successivamente divenne il direttore dei teatri dell'opera di Dresda e Lipsia; fu quindi ad Hannover nel periodo 1830-59, per dirigere la cappella di corte. Marschner fu fondamentalmente un compositore teatrale, fra le opere che gli conferirono maggior fama si annoverano: Der Vampyr (1828), Der templar und die Jüdin (1829) e un'opera di gusto popolare e leggendario, come è nel suo stile, intitolata Hans Heiling (1833), la quale ha alcune analogie con L'olandese volante di Richard Wagner. Caratteristica dell'arte di Marschner sono: la ricerca (nel melodramma) di soggetti soprannaturali caratteristici di quel senso puramente romantico di "orrore dilettevole", ma anche cavallereschi e soprattutto popolari, resi attraverso una ritmica incalzante, una vasta coloritura dei timbri orchestrali e con l'ausilio di numerosi leitmotiv e fili conduttori musicali. Non mancano inoltre nella sua produzione numerosi Lieder, due quartetti per pianoforte e ben sette trii per pianoforte particolarmente apprezzati da Robert Schumann. 2 3 HANS HEILING Tipo: Opera romantica in un prologo e tre atti Soggetto: libretto di Philipp Eduard Devrient Prima: Berlino, Königliches Opernhaus, 24 maggio 1833 Cast: la regina degli spiriti (S), Hans Heiling (Bar), Anna (S), Gertrude (A), Konrad (T), Stephan (B), Niklas (rec); spiriti, contadini, invitati, giocatori, tiratori Autore: Heinrich Marschner (1795-1861) Il personaggio di Hans Heiling, tra quelli creati da Marschner, rappresenta una delle più notevoli incarnazioni del tipico tema romantico dell’io diviso, condannato a non trovare la propria unità. -

The Impact of the Third Reich on Famous Composers by Bwaar Omer

The Impact of the Third Reich on Famous Composers By Bwaar Omer Germany is known as a land of poets and thinkers and has been the origin of many great composers and artists. In the early 1920s, the country was becoming a hub for artists and new music. In the time of the Weimar Republic during the roaring twenties, jazz music was a symbol of the time and it was used to represent the acceptance of the newly introduced cultures. Many conservatives, however, opposed this rise of for- eign culture and new music. Guido Fackler, a German scientist, contends this became a more apparent issue when Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) took power in 1933 and created the Third Reich. The forbidden music during the Third Reich, known as degen- erative music, was deemed to be anti-German and people who listened to it were not considered true Germans by nationalists. A famous composer who was negatively affected by the brand of degenerative music was Kurt Weill (1900-1950). Weill was a Jewish composer and playwright who was using his com- positions and stories in order to expose the Nazi agenda and criticize society for not foreseeing the perils to come (Hinton par. 11). Weill was exiled from Germany when the Nazi party took power and he went to America to continue his career. While Weill was exiled from Germany and lacked power to fight back, the Nazis created propaganda to attack any type of music associated with Jews and blacks. The “Entartete Musik” poster portrays a cartoon of a black individual playing a saxo- phone whose lips have been enlarged in an attempt to make him look more like an animal rather than a human. -

Der Vampyr De Heinrich Marschner

DESCUBRIMIENTOS Der Vampyr de Heinrich Marschner por Carlos Fuentes y Espinosa ay momentos extraordinarios Polidori creó ahí su obra más famosa y trascendente, pues introdujo en un breve cuento de en la historia de la Humanidad horror gótico, por vez primera, una concreción significativa de las creencias folclóricas sobre que, con todo gusto, el vampirismo, dibujando así el prototipo de la concepción que se ha tenido del monstruo uno querría contemplar, desde entonces, al que glorias de la narrativa fantástica como E.T.A. Hoffmann, Edgar Allan dada la importancia de la Poe, Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu, Jules Verne y el ineludible Abraham Stoker aprovecharían y Hproducción que en ellos se generara. ampliarían magistralmente. Sin duda, un momento especial para la literatura fantástica fue aquella reunión En su relato, Polidori presenta al vampiro, Lord Ruthven, como un antihéroe integrado, a de espléndidos escritores en Ginebra, su manera, a la sociedad, y no es difícil identificar la descripción de Lord Byron en él (sin Suiza, a mediados de junio de 1816 (el mencionar que con ese nombre ya una escritora amante de Byron, Caroline Lamb, nombraba “año sin verano”), cuando en la residencia como Lord Ruthven un personaje con las características del escritor). Precisamente por del célebre George Gordon, Lord Byron, eso, por la publicación anónima original, por la notoria emulación de las obras de Byron y a orillas del lago Lemán, departieron el su fama, las primeras ediciones del cuento se atribuyeron a él, aunque con el tiempo y una baronet Percy Bysshe Shelley, notable incómoda cantidad de disputas, terminara por dársele el crédito al verdadero escritor, que poeta y escritor, su futura esposa Mary fuera tío del poeta y pintor inglés Dante Gabriel Rossetti. -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Gustav Mahler, Alfred Roller, and the Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk: Tristan and Affinities Between the Arts at the Vienna Court Opera Stephen Carlton Thursby Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC GUSTAV MAHLER, ALFRED ROLLER, AND THE WAGNERIAN GESAMTKUNSTWERK: TRISTAN AND AFFINITIES BETWEEN THE ARTS AT THE VIENNA COURT OPERA By STEPHEN CARLTON THURSBY A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2009 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Stephen Carlton Thursby defended on April 3, 2009. _______________________________ Denise Von Glahn Professor Directing Dissertation _______________________________ Lauren Weingarden Outside Committee Member _______________________________ Douglass Seaton Committee Member Approved: ___________________________________ Douglass Seaton, Chair, Musicology ___________________________________ Don Gibson, Dean, College of Music The Graduate School has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To my wonderful wife Joanna, for whose patience and love I am eternally grateful. In memory of my grandfather, James C. Thursby (1926-2008). iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without the generous assistance and support of numerous people. My thanks go to the staff of the Austrian Theater Museum and Austrian National Library-Music Division, especially to Dr. Vana Greisenegger, curator of the visual materials in the Alfred Roller Archive of the Austrian Theater Museum. I would also like to thank the musicology faculty of the Florida State University College of Music for awarding me the Curtis Mayes Scholar Award, which funded my dissertation research in Vienna over two consecutive summers (2007- 2008). -

Apocalypticism in Wagner's Ring by Woodrow Steinken BA, New York

Title Page Everything That Is, Ends: Apocalypticism in Wagner’s Ring by Woodrow Steinken BA, New York University, 2015 MA, University of Pittsburgh, 2018 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2021 Committee Page UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Woodrow Steinken It was defended on March 23, 2021 and approved by James Cassaro, Professor, Music Adriana Helbig, Associate Professor, Music David Levin, Professor, Germanic Studies Dan Wang, Assistant Professor, Music Dissertation Director: Olivia Bloechl Professor, Music ii Copyright © by Woodrow Steinken 2021 iii Abstract Everything That Is, Ends: Apocalypticism in Wagner’s Ring Woodrow Steinken, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2021 This dissertation traces the history of apocalypticism, broadly conceived, and its realization on the operatic stage by Richard Wagner and those who have adapted his works since the late nineteenth century. I argue that Wagner’s cycle of four operas, Der Ring des Nibelungen (1876), presents colloquial conceptions of time, space, and nature via supernatural, divine characters who often frame the world in terms of non-rational metaphysics. Primary among these minor roles is Erda, the personification of the primordial earth. Erda’s character prophesies the end of the world in Das Rheingold, a prophecy undone later in Siegfried by Erda’s primary interlocutor and chief of the gods, Wotan. I argue that Erda’s role changes in various stage productions of the Ring, and these changes bespeak a shifting attachment between humanity, the earth, and its imagined apocalyptic demise. -

122 a Century of Grand Opera in Philadelphia. Music Is As Old As The

122 A Century of Grand Opera in Philadelphia. A CENTURY OF GRAND OPERA IN PHILADELPHIA. A Historical Summary read before the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Monday Evening, January 12, 1920. BY JOHN CURTIS. Music is as old as the world itself; the Drama dates from before the Christian era. Combined in the form of Grand Opera as we know it today they delighted the Florentines in the sixteenth century, when Peri gave "Dafne" to the world, although the ancient Greeks listened to great choruses as incidents of their comedies and tragedies. Started by Peri, opera gradually found its way to France, Germany, and through Europe. It was the last form of entertainment to cross the At- lantic to the new world, and while some works of the great old-time composers were heard in New York, Charleston and New Orleans in the eighteenth century, Philadelphia did not experience the pleasure until 1818 was drawing to a close, and so this city rounded out its first century of Grand Opera a little more than a year ago. But it was a century full of interest and incident. In those hundred years Philadelphia heard 276 different Grand Operas. Thirty of these were first heard in America on a Philadelphia stage, and fourteen had their first presentation on any stage in this city. There were times when half a dozen travelling companies bid for our patronage each season; now we have one. One year Mr. Hinrichs gave us seven solid months of opera, with seven performances weekly; now we are permitted to attend sixteen performances a year, unless some wandering organization cares to take a chance with us. -

A Special Catalogue of the Musical Material in the University of Illinois Library

A Special Catalogue of tfec !v , ;\h icn^ h the University of Illinois Ubrarj mic 1 !: K/V ut>ji\'.<ji«- J J JU .NO EE J.,.UMI AJtV THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY A SPECIAL CATALOGUE OF THE MUSICAL MATERIAL IN THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY BY DELLA GRACE CORDELL THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF MUSIC IN MUSIC SCHOOL OF MUSIC UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS 1918 Itns UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS June 13 19^8 THIS IS TO CERTIFY THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Delia Grace Qqx.gL.61L. entitled A Special Catalogue of the Musical .Material in the University of Illinois Library. IS APPROVED BY ME AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE of Bachelor of Music HEAD OF DEPARTMENT OF Director, School of Music i. Table of Contents. Theoretical music. Introduction. I. History 1. II. General theory 13. III. Theory of music education, and instruction 26. IV. Philosophy and esthetics 42. V. Criticism and essays 43. VI. Periodicals 45. Practical music. I. Voice 47. II. Sacred 72. III. Piano ?6. IV. Violin S3. V. Organ 88. VI. Ensemble 108. VII. Orchestral 127. Index 140. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/specialcatalogueOOuniv S Introduction. In making this special catalogue of the music material in the University of Illinois Library, the object in view was a classifi- cation of the music and musical books from the standpoint of the music student in order that the material be made more accessible to those wishing to use it. The mu3ic material is arranged on the shelves according to the library Dewey Decimal classification system by means of which all books are classified under ten main divisions.