Wall, Worlds of Echo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Voice Phenomenon Electronic

Praised by Morton Feldman, courted by John Cage, bombarded with sound waves by Alvin Lucier: the unique voice of singer and composer Joan La Barbara has brought her adventures on American contemporary music’s wildest frontiers, while her own compositions and shamanistic ‘sound paintings’ place the soprano voice at the outer limits of human experience. By Julian Cowley. Photography by Mark Mahaney Electronic Joan La Barbara has been widely recognised as a so particularly identifiable with me, although they still peerless interpreter of music by major contemporary want to utilise my expertise. That’s OK. I’m willing to composers including Morton Feldman, John Cage, share my vocabulary, but I’m also willing to approach a Earle Brown, Alvin Lucier, Robert Ashley and her new idea and try to bring my knowledge and curiosity husband, Morton Subotnick. And she has developed to that situation, to help the composer realise herself into a genuinely distinctive composer, what she or he wants to do. In return, I’ve learnt translating rigorous explorations in the outer reaches compositional tools by apprenticing, essentially, with of the human voice into dramatic and evocative each of the composers I’ve worked with.” music. In conversation she is strikingly self-assured, Curiosity has played a consistently important role communicating something of the commitment and in La Barbara’s musical life. She was formally trained intensity of vision that have enabled her not only as a classical singer with conventional operatic roles to give definitive voice to the music of others, in view, but at the end of the 1960s her imagination but equally to establish a strong compositional was captured by unorthodox sounds emanating from identity owing no obvious debt to anyone. -

KUNM 89.9 FM L February 2010

P KUNM 89.9 FM l February 2010 89.9 ALBUQUERQUE l 88.7 SOCORRO l 89.9 SANTA FE l 90.9 TAOS l 90.5 CIMARRON/EAGLE NEST 91.9 ESPANOLA l 91.9 LAS VEGAS l 91.9 NAGEEZI l 90.5 CUBA KUNM celebrates Black History Month! Alfre Woodard hosts Can Do: Stories of Black Visionaries, Seekers, and Entrepreneurs, and Iyah Music Host Anthony “Ijah” Umi speaks with Activist/Comedian/Philosopher Dick Gregory on The Spoken Word Hour. Details on Page 11. KUNM Operations Staff Elaine Baumgartel...............................................................................Reporter KUNM Radio Board Carol Boss.....................................................................Membership Relations Tristan Clum...............................................................Interim Program Director UNM Faculty Representatives: Briana Cristo..........................................................Vista Youth Radio Assistant Dorothy Baca Matthew Finch ...........................................................................Music Director John Scariano Roman Garcia .......................................................Interim Production Director UNM Staff Representative: Sarah Gustavus..................................................................................Reporter Mary Jacintha Rachel Kaub ....................................................................Operations Manager Elected Community Reps: Jonathan Longcore..............................................................IT Support Analyst Graham Sharman Linda Morris .........................................................Senior -

Drone Music from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Drone music From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Drone music Stylistic origins Indian classical music Experimental music[1] Minimalist music[2] 1960s experimental rock[3] Typical instruments Electronic musical instruments,guitars, string instruments, electronic postproduction equipment Mainstream popularity Low, mainly in ambient, metaland electronic music fanbases Fusion genres Drone metal (alias Drone doom) Drone music is a minimalist musical style[2] that emphasizes the use of sustained or repeated sounds, notes, or tone-clusters – called drones. It is typically characterized by lengthy audio programs with relatively slight harmonic variations throughout each piece compared to other musics. La Monte Young, one of its 1960s originators, defined it in 2000 as "the sustained tone branch of minimalism".[4] Drone music[5][6] is also known as drone-based music,[7] drone ambient[8] or ambient drone,[9] dronescape[10] or the modern alias dronology,[11] and often simply as drone. Explorers of drone music since the 1960s have included Theater of Eternal Music (aka The Dream Syndicate: La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela, Tony Conrad, Angus Maclise, John Cale, et al.), Charlemagne Palestine, Eliane Radigue, Philip Glass, Kraftwerk, Klaus Schulze, Tangerine Dream, Sonic Youth,Band of Susans, The Velvet Underground, Robert Fripp & Brian Eno, Steven Wilson, Phill Niblock, Michael Waller, David First, Kyle Bobby Dunn, Robert Rich, Steve Roach, Earth, Rhys Chatham, Coil, If Thousands, John Cage, Labradford, Lawrence Chandler, Stars of the Lid, Lattice, -

Garrett List

Garrett List Information Discographie Agenda des concerts Trombone, Compositeur, Instrument(s) Arrangeur, Chant Date de 1943 naissance Lieu de Phoenix, U.S.A naissance Contacts Email Envoyer un email Site web Site web dédié © Christian Deblanc Text also available in English Né à Phoenix (Arizona) Garrett LIST joue du trombone et chante depuis l'âge de sept ans. A dix-huit ans, lorsqu'il entre à l'Université;, il a déjà une vie professionnelle et pédagogique remplie, il joue autant de la musique classique que d'autres styles (jazz, pop, blues), tout en donnant des cours aux enfants. Il s'adonne aussi à la composition. En 1965, il part pour New York pour y suivre des études strictement classiques à la célèbre Juilliard School of Music. Il y rencontre le compositeur italien Luciano BERIO et le chef d'orchestre Dennis RUSSELL DAVIES avec qui il forme le Juillard Ensemble. Grâce à cet ensemble, il rencontre aussi les compositeurs Henri POUSSEUR et Pierre BOULEZ et se met à jouer leurs musiques. Il entreprend plusieurs tournées en Europe et enregistre. Après cette immersion totale dans la musique contemporaine et ces études intenses au conservatoire Juilliard, il ressent le besoin d'une autre vision de la création musicale. C'est l'époque du free jazz et New York est sous le choc de mai '68. Il découvre l'improvisation, pas seulement dans le cadre du jazz ou du blues, mais la considère comme une manière de vivre la création musicale de l'intérieur. Il rencontre alors John CAGE, Frederic RZEWSKI, LaMonte YOUNG, Rhys CHATHAM, Anthony BRAXTON, Steve LACY et devient membre du Musica Eletronica Viva, un des groupes les plus influents de la musique improvisée de l'époque. -

(718) 636-4123 for IMMEDIATE RELEASE October 24, 1984

NEWS CONTACT: fllen Ldmpert FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Susan Spier October 24, 1984 (718) 636-4123 RICHARD LANDRY PERFORMS IN BAM'S NEXT WAVE FESTIVAL ON NOVE~1BER 10, 1984 Saxophonist and composer RICHARD LANDRY will make his first New York solo appearance in over two years in the Brooklyn Academy of Music's NEXT WAVE FESTIVAL on November 10, 1984. Joining Richard Landry in the second half of his concert is guest percussionist David Van Tieghem. Born and raised in Cecilia, Louisiana, where he still resides, Richard Landry's roots are in Cajun music, rural southern rhythm and blues, and jazz. His concerts are distinguished by virtuosic improvisations on the uncharted range of the tenor saxophone, processed through a quadrophonic delay system which allows him to form his own quintet. He has also performed and recorded with Steve Reich and Musicians, the Philip Glass Ensemble, Talking Heads, and Laurie Anderson, while presenting more than two hundred solo concerts throughout the United States, Canada, and Europe. Richard Landry's concert for tenor saxophone will be held in BAM's Carey Playhouse on Saturday, November 10, at 8:00pm. Tickets are $15.00 . The NEXT WAVE Production and Touring Fund is supported by the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Rockefeller Foundation, the Howard Gilman Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the Pew Memorial Trust, AT&T, WilliWear Ltd., Warner Communications Inc. , the Educational Foundation of America, the CIGNA Corporation, the Best Products Foundation, Abraham & Straus/Federated Department Stores Foundation, Inc. and the BAM NEXT WAVE Producers Council. -

The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976 David Allen Chapman Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) Spring 4-27-2013 Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976 David Allen Chapman Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Chapman, David Allen, "Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The hiP lip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976" (2013). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 1098. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/1098 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of Music Dissertation Examination Committee: Peter Schmelz, Chair Patrick Burke Pannill Camp Mary-Jean Cowell Craig Monson Paul Steinbeck Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966–1976 by David Allen Chapman, Jr. A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 St. Louis, Missouri © Copyright 2013 by David Allen Chapman, Jr. All rights reserved. CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................... -

NEA-Annual-Report-1992.Pdf

N A N A L E ENT S NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR~THE ARTS 1992, ANNUAL REPORT NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR!y’THE ARTS The Federal agency that supports the Dear Mr. President: visual, literary and pe~orming arts to I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report benefit all A mericans of the National Endowment for the Arts for the fiscal year ended September 30, 1992. Respectfully, Arts in Education Challenge &Advancement Dance Aria M. Steele Design Arts Acting Senior Deputy Chairman Expansion Arts Folk Arts International Literature The President Local Arts Agencies The White House Media Arts Washington, D.C. Museum Music April 1993 Opera-Musical Theater Presenting & Commissioning State & Regional Theater Visual Arts The Nancy Hanks Center 1100 Pennsylvania Ave. NW Washington. DC 20506 202/682-5400 6 The Arts Endowment in Brief The National Council on the Arts PROGRAMS 14 Dance 32 Design Arts 44 Expansion Arts 68 Folk Arts 82 Literature 96 Media Arts II2. Museum I46 Music I94 Opera-Musical Theater ZlO Presenting & Commissioning Theater zSZ Visual Arts ~en~ PUBLIC PARTNERSHIP z96 Arts in Education 308 Local Arts Agencies State & Regional 3z4 Underserved Communities Set-Aside POLICY, PLANNING, RESEARCH & BUDGET 338 International 346 Arts Administration Fallows 348 Research 35o Special Constituencies OVERVIEW PANELS AND FINANCIAL SUMMARIES 354 1992 Overview Panels 360 Financial Summary 36I Histos~f Authorizations and 366~redi~ At the "Parabolic Bench" outside a South Bronx school, a child discovers aspects of sound -- for instance, that it can be stopped with the wave of a hand. Sonic architects Bill & Mary Buchen designed this "Sound Playground" with help from the Design Arts Program in the form of one of the 4,141 grants that the Arts Endowment awarded in FY 1992. -

University of California Santa Cruz

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ EXTENDED FROM WHAT?: TRACING THE CONSTRUCTION, FLEXIBLE MEANING, AND CULTURAL DISCOURSES OF “EXTENDED VOCAL TECHNIQUES” A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in MUSIC by Charissa Noble March 2019 The Dissertation of Charissa Noble is approved: Professor Leta Miller, chair Professor Amy C. Beal Professor Larry Polansky Lori Kletzer Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Charissa Noble 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures v Abstract vi Acknowledgements and Dedications viii Introduction to Extended Vocal Techniques: Concepts and Practices 1 Chapter One: Reading the Trace-History of “Extended Vocal Techniques” Introduction 13 The State of EVT 16 Before EVT: A Brief Note 18 History of a Construct: In Search of EVT 20 Ted Szántó (1977): EVT in the Experimental Tradition 21 István Anhalt’s Alternative Voices (1984): Collecting and Codifying EVT 28evt in Vocal Taxonomies: EVT Diversification 32 EVT in Journalism: From the Musical Fringe to the Mainstream 42 EVT and the Classical Music Framework 51 Chapter Two: Vocal Virtuosity and Score-Based EVT Composition: Cathy Berberian, Bethany Beardslee, and EVT in the Conservatory-Oriented Prestige Economy Introduction: EVT and the “Voice-as-Instrument” Concept 53 Formalism, Voice-as-Instrument, and Prestige: Understanding EVT in Avant- Garde Music 58 Cathy Berberian and Luciano Berio 62 Bethany Beardslee and Milton Babbitt 81 Conclusion: The Plight of EVT Singers in the Avant-Garde -

Battles Around New Music in New York in the Seventies

Presenting the New: Battles around New Music in New York in the Seventies A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Joshua David Jurkovskis Plocher IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY David Grayson, Adviser December 2012 © Joshua David Jurkovskis Plocher 2012 i Acknowledgements One of the best things about reaching the end of this process is the opportunity to publicly thank the people who have helped to make it happen. More than any other individual, thanks must go to my wife, who has had to put up with more of my rambling than anybody, and has graciously given me half of every weekend for the last several years to keep working. Thank you, too, to my adviser, David Grayson, whose steady support in a shifting institutional environment has been invaluable. To the rest of my committee: Sumanth Gopinath, Kelley Harness, and Richard Leppert, for their advice and willingness to jump back in on this project after every life-inflicted gap. Thanks also to my mother and to my kids, for different reasons. Thanks to the staff at the New York Public Library (the one on 5th Ave. with the lions) for helping me track down the SoHo Weekly News microfilm when it had apparently vanished, and to the professional staff at the New York Public Library for Performing Arts at Lincoln Center, and to the Fales Special Collections staff at Bobst Library at New York University. Special thanks to the much smaller archival operation at the Kitchen, where I was assisted at various times by John Migliore and Samara Davis. -

1984 Category Artist(S)

1984 Category Artist(s) Artist/Title Of Work Venue Choreographer/Creator Anne Bogart South Pacific NYU Experimental Theatear Wing Eiko & Koma Grain/Night Tide DTW Fred Holland/Ishmael Cowboys, Dreams, and Ladders The Kitchen Houston Jones Julia Heyward No Local Stops Ohio Space Mark Morris Season DTW Nina Wiener Wind Devil BAM Stephanie Skura It's Either Now or Later/Art Business DTW, P.S. 122 Timothy Buckley Barn Fever The Kitchen Yoshiko Chuma and the Collective Work School of Hard Knocks Composer Anthony Davis Molissa Fenley/Hempshires BAM Lenny Pickett Stephen Pertronio/Adrift (With Clifford Danspace Project Arnell) Film & TV/Choreographer Frank Moore & Jim Self Beehive Nancy Mason Hauser & Dance Television Workshop at WGBH- Susan Dowling TV Lighting Designer Beverly Emmons Sustained Achievement Carol Mulins Body of Work Danspace Project Jennifer Tipton Sustained Achievement Performer Chuck Greene Sweet Saturday Night (Special Citation) BAM John McLaughlin Douglas Dunn/ Diane Frank/ Deborah Riley Pina Bausch and the 1980 (Special Citation) BAM Wuppertaler Tanztheatre Rob Besserer Lar Lubovitch and Others Sara Rudner Twyla Tharp Steven Humphrey Garth Fagan Valda Setterfield David Gordon Special Achievement/Citations Studies Project of Movement Research, Inc./ Mary Overlie, Wendell Beavers, Renee Rockoff David Gordon Framework/ The Photographer/ DTW, BAM Sustained Achievement Trisha Brown Set and Reset/ Sustained Achievement BAM Visual Designer Judy Pfaff Nina Wiener/Wind Devil Power Boothe Charles Moulton/ Variety Show; David DTW, The Joyce Gordon/ Framework 1985 Category Artist(s) Artist/Title of Work Venue Choreographer/Creator Cydney Wilkes 16 Falls in Color & Searching for Girl DTW, Ethnic Folk Arts Center Johanna Boyce Johanna Boyce with the Calf Women & DTW Horse Men John Jesurun Chang in a Void Moon Pyramid Club Bottom Line Judith Ren-Lay The Grandfather Tapes Franklin Furnace Susan Marshall Concert DTW Susan Rethorst Son of Famous Men P. -

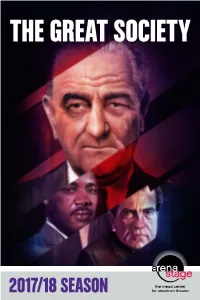

The Great Society Program Book Published February 2, 2018

THE GREAT SOCIETY 2017/18 SEASON COMING IN 2018 TO ARENA STAGE Part of the Women’s American Masterpiece Voices Theater Festival SOVEREIGNTY AUGUST WILSON’S NOW PLAYING THROUGH FEBRUARY 18 TWO TRAINS Epic Political Thrill Ride RUNNING THE GREAT SOCIETY MARCH 30 — APRIL 29 NOW PLAYING THROUGH MARCH 11 World-Premiere Musical Inspirational True Story SNOW CHILD HOLD THESE TRUTHS APRIL 13 — MAY 20 FEBRUARY 23 — APRIL 8 SUBSCRIBE TODAY! 202-488-3300 ARENASTAGE.ORG THE GREAT SOCIETY TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 Artistically Speaking 5 From the Executive Director 6 Molly Smith’s 20th Anniversary Season 9 Dramaturg’s Note 11 Title Page 13 Time / Cast List 15 Bios — Cast 19 Bios — Creative Team 21 For this Production 23 Arena Stage Leadership ARENA STAGE 1101 Sixth Street SW Washington, DC 20024-2461 24 Board of Trustees / Theatre Forward ADMINISTRATION 202-554-9066 SALES OFFICE 202-488-3300 TTY 202-484-0247 25 Full Circle Society arenastage.org 26 Thank You — The Annual Fund © 2018 Arena Stage. All editorial and advertising material is fully protected and must not 29 Thank You — Institutional Donors be reproduced in any manner without written permission. 30 Theater Staff The Great Society Program Book Published February 2, 2018 Cover Illustration by Richard Davies Tom Program Book Staff Amy Horan, Associate Director of Marketing Shawn Helm, Graphic Designer 2017/18 SEASON 3 ARTISTICALLY SPEAKING Historians often argue whether history is cyclical or linear. The Great Society makes an argument for both sides of this dispute. Taking place during the most tumultuous days in Lyndon Baines Johnson’s (LBJ) second term, this play depicts the president fighting wars both at home and abroad as he faces opposition to his domestic programs and the role of the United States in the Vietnam War. -

At the W Ardrobe Info 0113 269 4077

Brad Shepik was born in Walla Walla,Washington 1966 and raised in Seattle. He played Wednesday November 10 The Wardrobe £10/8 guitar and saxophone in school bands and attended Cornish College of the Arts where he Brad Shepik Trio studied with Jerry Granelli, Julian Priester, Dave Peck, James Knapp, Dave Petersen and Brad Shepik – guitar, saxaphone Ralph Towner. Tom Rainey – drums In 1990 Brad moved to New York and dived head first into the music scene. He quickly Matt Penman – bass became involved in the formation of a loose collective of improvising musicians who were into experimenting and playing each other’s music, as well as different folk musics including Balkan and Eastern European musics. Out of this environment was born many groups that Shepik continues to perform with today including the Tiny Bell Trio 1992, Paradox Trio 1992, Pachora 1993, and BABKAS 1992–8. In 1991 Bill Frisell recommended Shepik to Paul Motion for his Electric Be Bop Band which Shepik toured and recorded with for five years. “Shepik’s got the mind of a pioneer.The rhythmic complexity of his compositions has few parallels in jazz – or any other genre,for that matter.With all his exotic influences, and all his different axes,he makes us rethink what it means to be a guitarist and a musician.There’s no telling where he’ll go next.” allaboutjazz.com Iconoclastic and prolific jazz-rock guitarist David ‘Fuze’ Fiuczynski, a jazz player who “doesn’t want to Thursday November 18 The Wardrobe £12/10 play just jazz”, has been hailed by the world press as an incredibly inventive guitar hero, who continues Screaming Headless Torsos to deliver with music that is unclassifiable, challenging and invigorating.