The Significance of a Life's Shape Dale Dorsey Department Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Bulletin

WANADA Bulletin #28-05 *Special Issue* July 13, 2005 2005 BOBBY MITCHELL HALL OF FAME GOLF CLASSIC Strong Dealer Support Helps Classic Raise Record $680,000 for Leukemia & Lymphoma Research! A moving video and testimonial by the Fertitta family (above left) helped inspire over 600 guests at Saturday night’s banquet to raise an astounding $680,000 for blood cancer research. t was truly an evening to remem- I ber. Not only was the 15th Anni- versary Bobby Mitchell/Toyota Hall of Fame Classic sponsored by the Washington Area Auto Dealers the largest gathering ever of Hall of Fame sports legends, it set a phe- nomenal fundraising record – $680,000 – for the benefit of the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society. That is a 36% increase over the $505,000 raised last year, taking the Clockwise from above, Classic total raised by the Classic to well Co-Chair Tammy Darvish drum- over $4 million, with nearly $2.5 ming up support; Paul Berry million coming in the past five years, with Leukemia survivors (from since WANADA got involved as a left) Brandon Ward, 12, principal sponsor. Ashlynn Prins, 6, Carter Beardsley, 7; and Christopher Hosted by Lansdowne Resort this Scheller, 10; and Bobby Mitchell past weekend, the spectacular event with Sonny Jurgensen and was the result of the commitment Sam Huff at “Press Day,” which and support of over 40 NFL and kicked off this year’s Classic. NBA Hall of Famers, the dynamic leadership of event chairman Bobby Mitchell and co-chairs Tammy Inside… Darvish of DARCARS Automotive Bobby Mitchell Golf Classic Highlights……………………...….p.2 & 3 Hall of Fame Sponsors…………………………………………….….…p.4 (Continued on page 2) Page 2 July 13, 2005 WANADA Bulletin #28-05 2005 BOBBY MITCHELL HALL OF FAME GOLF CLASSIC As always, the stars of the event were the Hall of Fame greats, seen here with WANADA leadership. -

American Cancer Society Fauquier County Relay for Life Silent

American Cancer Society Fauquier County Relay for Life 5/3/2014 Silent Auction Item List Auction Start - 12:00 Noon Auction Close - 5:00 PM Retail Min. Bid Item # Item Description Starting Bid Price Increment Derek Jeter Autographed #1 of Only 2 Limited Edition 3000th Hit Official Major League Rawlings Baseball and Yankees All Time Hits Leader Commemorative Bat #63 of 2674 & artist signed Lithograph You are bidding on two very rare items autographed by Derek Jeter. First we have an extremely rare limited edition baseball commemorating Derek Jeter’s 3,000th hit. There were only two of these baseballs commissioned and this baseball is the 1st ball in this set of 2 This ball has gold lettering under the signature that says: Derek Jeter #2 3,000th hit off David Price Home Run to Left Field est @ 001 July 9, 2011 vs. the TB Rays $2500.00 + $2,000.00 $50.00 Yankee Stadium display case Limited Edition #1 of 2" This extremely rare baseball comes with a full letter from JSA. This ball is difficult to price since there is only two of this limited edition and is estimated between $1,200.00 - $1,400.00. The 2nd item is a Black Louisville Slugger Yankees Bat commemorating Derek Jeter’s status as the all- time MLB hits leader at the Shortstop Position with his 2, 674th hit on August 16, 2009. The bat is #63 of only 2674 made. The bat comes with a Steiner tamperproof hologram stick on the bat and matching COA. Similar bats sells for $1000.00 - 1,200.00 at SportsMemorabilia.com, Amazon, Mounted Memories, Steiner Sports and other sports memorabilia stores. -

Bobby Mitchell

PRO FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME TEACHER ACTIVITY GUIDE 2019-2020 EDITIOn WASHInGTOn REDSKInS Team History With three Super Bowl championships, the Washington Redskins are one of the NFL’s most dominant teams of the past quarter century. But the organization’s glorious past dates back almost 60 years and includes five world championships overall and some of the most innovative people and ideas the game has ever known. From George Preston Marshall to Jack Kent Cooke, from Vince Lombardi to Joe Gibbs, from Sammy Baugh to John Riggins, plus the NFL’s first fight song, marching band and radio network, the Redskins can be proud of an impressive professional football legacy. George Preston Marshall was awarded the inactive Boston franchise in July 1932. He originally named the team “Braves” because it used Braves Field, home of the National League baseball team. When the team moved to Fenway Park in July 1933, the name was changed to Redskins. A bizarre situation occurred in 1936, when the Redskins won the NFL Eastern division championship but Marshall, unhappy with the fan support in Boston,moved the championship game against Green Bay to the Polo Grounds in New York. Their home field advantage taken away by their owner, the Redskins lost. Not surprisingly, the Redskins moved to Washington, D.C., for the 1937 season. Games were played in Griffith Stadium with the opener on September 16, 1937, being played under flood lights. That year,Marshall created an official marching band and fight song, both firsts in the National Football League. That season also saw the debut of “Slinging Sammy” Baugh, a quarterback from Texas Christian who literally changed the offensive posture of pro football with his forward passing in his 16-season career. -

17 Finalists for Hall of Fame Election

For Immediate Release For More Information, Contact: January 10, 2007 Joe Horrigan at (330) 456-8207 17 FINALISTS FOR HALL OF FAME ELECTION Paul Tagliabue, Thurman Thomas, Michael Irvin, and Bruce Matthews are among the 17 finalists that will be considered for election to the Pro Football Hall of Fame when the Hall’s Board of Selectors meets in Miami, Florida on Saturday, February 3, 2007. Joining these four finalists, are 11 other modern-era players and two players nominated earlier by the Hall of Fame’s Senior Committee. The Senior Committee nominees, announced in August 2006, are former Cleveland Browns guard Gene Hickerson and Detroit Lions tight end Charlie Sanders. The other modern-era player finalists include defensive ends Fred Dean and Richard Dent; guards Russ Grimm and Bob Kuechenberg; punter Ray Guy; wide receivers Art Monk and Andre Reed; linebackers Derrick Thomas and Andre Tippett; cornerback Roger Wehrli; and tackle Gary Zimmerman. To be elected, a finalist must receive a minimum positive vote of 80 percent. Listed alphabetically, the 17 finalists with their positions, teams, and years active follow: Fred Dean – Defensive End – 1975-1981 San Diego Chargers, 1981- 1985 San Francisco 49ers Richard Dent – Defensive End – 1983-1993, 1995 Chicago Bears, 1994 San Francisco 49ers, 1996 Indianapolis Colts, 1997 Philadelphia Eagles Russ Grimm – Guard – 1981-1991 Washington Redskins Ray Guy – Punter – 1973-1986 Oakland/Los Angeles Raiders Gene Hickerson – Guard – 1958-1973 Cleveland Browns Michael Irvin – Wide Receiver – 1988-1999 -

15 Finalists for Hall of Fame Election

For Immediate Release For More Information, Contact January 11, 2006 Joe Horrigan at (330) 456-8207 15 FINALISTS FOR HALL OF FAME ELECTION Troy Aikman, Warren Moon, Thurman Thomas, and Reggie White, four first-year eligible candidates, are among the 15 finalists who will be considered for election to the Pro Football Hall of Fame when the Hall’s Board of Selectors meets in Detroit, Michigan on Saturday, February 4, 2006. Joining the first-year eligible players as finalists, are nine other modern-era players and a coach and player nominated earlier by the Hall of Fame’s Seniors Committee. The Seniors Committee nominees, announced in August 2005, are John Madden and Rayfield Wright. The other modern-era player finalists include defensive ends L.C. Greenwood and Claude Humphrey; linebackers Harry Carson and Derrick Thomas; offensive linemen Russ Grimm, Bob Kuechenberg and Gary Zimmerman; and wide receivers Michael Irvin and Art Monk. To be elected, a finalist must receive a minimum positive vote of 80 percent. Listed alphabetically, the 15 finalists with their positions, teams, and years follow: Troy Aikman – Quarterback – 1989–2000 Dallas Cowboys Harry Carson – Linebacker – 1976-1988 New York Giants L.C. Greenwood – Defensive End – 1969-1981 Pittsburgh Steelers Russ Grimm – Guard – 1981-1991 Washington Redskins Claude Humphrey – Defensive End – 1968-1978 Atlanta Falcons, 1979-1981 Philadelphia Eagles (injured reserve – 1975) Michael Irvin – Wide Receiver – 1988-1999 Dallas Cowboys Bob Kuechenberg – Guard – 1970-1984 Miami Dolphins -

1985 Topps Football Card Checklist

1985 TOPPS FOOTBALL CARD CHECKLIST 1 Mark Clayton (Record Breaker) 2 Eric Dickerson (Record Breaker) 3 Charlie Joiner (Record Breaker) 4 Dan Marino (Record Breaker) 5 Art Monk (Record Breaker) 6 Walter Payton (Record Breaker) 7 NFC Championship 8 AFC Championship (Dolphins Vs. Steelers) 9 Super Bowl XIX (49ers Vs. Dolphins) 10 Falcons Team Ldrs. (Gerald Riggs) 11 William Andrews 12 Stacey Bailey 13 Steve Bartkowski 14 Rick Bryan 15 Alfred Jackson 16 Kenny Johnson 17 Mike Kenn (All Pro) 18 Mike Pitts 19 Gerald Riggs 20 Sylvester Stamps 21 R.C. Thielemann 22 Bears Team Leaders (Walter Payton) 23 Todd Bell (All Pro) 24 Richard Dent (All Pro) 25 Gary Fencik 26 Dave Finzer 27 Leslie Frazier 28 Steve Fuller 29 Willie Gault 30 Dan Hampton (All Pro) 31 Jim McMahon 32 Steve McMichael 33 Walter Payton (All Pro) 34 Mike Singletary 35 Matt Suhey 36 Bob Thomas 37 Cowboys Team Ldrs. (Tony Dorsett) 38 Bill Bates 39 Doug Cosbie 40 Tony Dorsett 41 Michael Downs 42 Mike Hegman Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 43 Tony Hill 44 Gary Hogeboom 45 Jim Jeffcoat 46 Ed "Too Tall" Jones 47 Mike Renfro 48 Rafael Septien 49 Dennis Thurman 50 Everson Walls 51 Danny White 52 Randy White 53 Lions Team Leaders (Lions' Defense) 54 Jeff Chadwick 55 Mike Cofer 56 Gary Danielson 57 Keith Dorney 58 Doug English 59 William Gay 60 Ken Jenkins 61 James Jones 62 Ed Murray 63 Billy Sims 64 Leonard Thompson 65 Bobby Watkins 66 Packers Team Ldrs. (Lynn Dickey) 67 Paul Coffman 68 Lynn Dickey 69 Mike Douglass 70 Tom Flynn 71 Eddie Lee Ivery 72 Ezra Johnson 73 Mark Lee 74 Tim Lewis 75 James Lofton 76 Bucky Scribner 77 Rams Team Leaders (Eric Dickerson) 78 Nolan Cromwell 79 Eric Dickerson (All Pro) 80 Henry Ellard 81 Kent Hill 82 Le Roy Irvin 83 Jeff Kemp 84 Mike Lansford 85 Barry Redden 86 Jackie Slater 87 Doug Smith 88 Jack Youngblood 89 Vikings Team Ldrs. -

Pro Football Hall of Fame

PRO FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME The Professional Football Hall Between four and seven new MARCUS ALLEN CLIFF BATTLES of Fame is located in Canton, members are elected each Running back. 6-2, 210. Born Halfback. 6-1, 195. Born in Ohio, site of the organizational year. An affirmative vote of in San Diego, California, Akron, Ohio, May 1, 1910. meeting on September 17, approximately 80 percent is March 26, 1960. Southern Died April 28, 1981. West Vir- 1920, from which the National needed for election. California. Inducted in 2003. ginia Wesleyan. Inducted in Football League evolved. The Any fan may nominate any 1982-1992 Los Angeles 1968. 1932 Boston Braves, NFL recognized Canton as the eligible player or contributor Raiders, 1993-1997 Kansas 1933-36 Boston Redskins, Hall of Fame site on April 27, simply by writing to the Pro City Chiefs. Highlights: First 1937 Washington Redskins. 1961. Canton area individuals, Football Hall of Fame. Players player in NFL history to tally High lights: NFL rushing foundations, and companies and coaches must have last 10,000 rushing yards and champion 1932, 1937. First to donated almost $400,000 in played or coached at least five 5,000 receiving yards. MVP, gain more than 200 yards in a cash and services to provide years before he is eligible. Super Bowl XVIII. game, 1933. funds for the construction of Contributors (administrators, the original two-building com- owners, et al.) may be elected LANCE ALWORTH SAMMY BAUGH plex, which was dedicated on while they are still active. Wide receiver. 6-0, 184. Born Quarterback. -

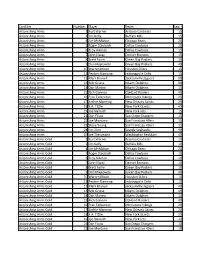

Card Set Number Player Team Seq. Astonishing Arms 1 Kurt Warner

Card Set Number Player Team Seq. Astonishing Arms 1 Kurt Warner Arizona Cardinals 15 Astonishing Arms 2 Jim Kelly Buffalo Bills 15 Astonishing Arms 4 Jim McMahon Chicago Bears 25 Astonishing Arms 5 Roger Staubach Dallas Cowboys 15 Astonishing Arms 6 Troy Aikman Dallas Cowboys 15 Astonishing Arms 7 John Elway Denver Broncos 15 Astonishing Arms 8 Brett Favre Green Bay Packers 15 Astonishing Arms 9 Don Majkowski Green Bay Packers 49 Astonishing Arms 10 Warren Moon Houston Oilers 15 Astonishing Arms 11 Peyton Manning Indianapolis Colts 15 Astonishing Arms 12 Mark Brunell Jacksonville Jaguars 99 Astonishing Arms 13 Bob Griese Miami Dolphins 99 Astonishing Arms 14 Dan Marino Miami Dolphins 15 Astonishing Arms 15 Rich Gannon Oakland Raiders 49 Astonishing Arms 16 Fran Tarkenton Minnesota Vikings 25 Astonishing Arms 17 Archie Manning New Orleans Saints 25 Astonishing Arms 18 Y.A. Tittle New York Giants 49 Astonishing Arms 19 Joe Namath New York Jets 15 Astonishing Arms 21 Dan Fouts San Diego Chargers 15 Astonishing Arms 22 Joe Montana San Francisco 49ers 15 Astonishing Arms 23 Steve Young San Francisco 49ers 15 Astonishing Arms 24 Jim Zorn Seattle Seahawks 99 Astonishing Arms 25 Joe Theismann Washington Redskins 49 Astonishing Arms Gold 1 Kurt Warner Arizona Cardinals 10 Astonishing Arms Gold 2 Jim Kelly Buffalo Bills 10 Astonishing Arms Gold 4 Jim McMahon Chicago Bears 20 Astonishing Arms Gold 5 Roger Staubach Dallas Cowboys 10 Astonishing Arms Gold 6 Troy Aikman Dallas Cowboys 10 Astonishing Arms Gold 7 John Elway Denver Broncos 10 Astonishing -

15 Modern-Era Finalists for Hall of Fame Election Announced

For Immediate Release For More Information, Contact: January 11, 2013 Joe Horrigan at (330) 588-3627 15 MODERN-ERA FINALISTS FOR HALL OF FAME ELECTION ANNOUNCED Four first-year eligible nominees – Larry Allen, Jonathan Ogden, Warren Sapp, and Michael Strahan – are among the 15 modern-era finalists who will be considered for election to the Pro Football Hall of Fame when the Hall’s Selection Committee meets in New Orleans, La. on Saturday, Feb. 2, 2013. Joining the first-year eligible, are eight other modern-era players, a coach and two contributors. The 15 modern-era finalists, along with the two senior nominees announced in August 2012 (former Kansas City Chiefs and Houston Oilers defensive tackle Curley Culp and former Green Bay Packers and Washington Redskins linebacker Dave Robinson) will be the only candidates considered for Hall of Fame election when the 46-member Selection Committee meets. The 15 modern-era finalists were determined by a vote of the Hall’s Selection Committee from a list of 127 nominees that earlier was reduced to a list of 27 semifinalists, during the multi-step, year-long selection process. Culp and Robinson were selected as senior candidates by the Hall of Fame’s Seniors Committee. The Seniors Committee reviews the qualifications of those players whose careers took place more than 25 years ago. To be elected, a finalist must receive a minimum positive vote of 80 percent. The Pro Football Hall of Fame Selection Committee’s 17 finalists (15 modern-era and two senior nominees*) with their positions, teams, and years active follow: • Larry Allen – Guard/Tackle – 1994-2005 Dallas Cowboys; 2006-07 San Francisco 49ers • Jerome Bettis – Running Back – 1993-95 Los Angeles/St. -

Patriots Coaching Staff

JUST ONE" TABLE OF CONTENTS Biographies: Assistant Coaches .................................. 7-9 Draft Choices, 1979 .................................... 38-40 t 6 Rm��� s�i�ci: : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : 5 Sullivan, William H., Jr................................... 4 Veteran Players. ................................ 10-34 Building the Patriots 36 Final 1978 Team Statistics .. 60-61 Historical Highlights of the Patriots. 68-69 Hotels on the Road... ....... 52 Important NFL Dates, 1979-80. 119 Listings: 100-Yard Rushing Games............... ............... 73 100 Games Played as a Patriot . .. .. .. ............. 80 300-Yard Passing Games .................. ............ 53 ; nF�t/ear-by-Year, Home and Away 67 ��:�J , . _ _ : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : 41 Awards, Post-Season ...................................... 57 Club Directory .. .. .. .. .. .......... 3 Crowds, Largest . .. .. .. .. ........... 70 Extra Points, by Kick . ............................. 73 Field Goals, All-Time . .............. .. 74 Field Goals, Year-by-Year 74 Head Coaches, Won and Lost .............. 9 lnterceRtors, Top 10...................................... 103 Kickoff Returners, Top 20 ................ 105 Last Time It Happened ................... .. .. 80 Leaders, Various Categories, Year-by-Year .............. 71-74 Passers, Top 10 . .. .. ............................... 103 Points, b'i_K1cking.... 74 Punters Top 10....... 105 Punt Re! urners, Top 20.......................... 105 Receivers, Top 30. -

(330) 456-8207 15 Modern-Era Finalists F

For Immediate Release For More Information, Contact: January 7, 2012 Joe Horrigan at (330) 456-8207 15 MODERN-ERA FINALISTS FOR HALL OF FAME ELECTION ANNOUNCED Two first-year eligible nominees – coach Bill Parcells and tackle Will Shields – are among the 15 modern-era finalists who will be considered for election to the Pro Football Hall of Fame when the Hall’s Selection Committee meets in Indianapolis, Ind. on Saturday, Feb. 4, 2012. Joining the first-year eligible, are 12 modern-era players and a contributor. The 15 modern-era finalists, along with the two senior nominees announced in August 2011 (former Pittsburgh Steelers cornerback Jack Butler and former Detroit Lions and Washington Redskins guard Dick Stanfel) will be the only candidates considered for Hall of Fame election when the 44-member Selection Committee meets. To be elected, a finalist must receive a minimum positive vote of 80 percent. Although technically a first-year eligible candidate, Parcells has been a finalist twice before (2001, 2002) following his announced retirement as head coach of the New York Jets in 1999. At the time the Hall of Fame By-Laws did not require a coach to be retired the now mandatory five seasons. Parcells returned to coach the Dallas Cowboys in 2003 and the five-year waiting period was in effect when he retired from coaching in 2006. The Pro Football Hall of Fame Selection Committee’s 17 finalists (15 modern-era and two senior nominees*) with their positions, teams, and years active follow: Jerome Bettis – Running Back – 1993-95 Los Angeles/St. -

John Riggins the Diesel

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 16, No. 2 (1994) JOHN RIGGINS THE DIESEL By Don Smith John Riggins was an all-America running back at the University of Kansas where he surpassed most of Gale Sayers' rushing records. He was the No. 1 draft choice of the New York Jets and the sixth player chosen in the 1971 NFL draft. Yet he wasn't at all sure he would make it in the pros. "I wasn't a very good player in college, to tell you the truth," he insisted. "I thought I might be the first No. 1 draft choice to be cut. I'd seen a few big names flop just ahead of me." But Riggins was not cut. Instead he launched a 14-year pro career that saw him play five seasons with the Jets and nine years with the Washington Redskins. In 14 seasons, he rushed for 11,352 yards, the sixth highest total of all time, and he accounted for 13,435 combined net yards, ninth most ever. His 116 career touchdowns and 104 rushing touchdowns are both No. 3 in the record book. Those achievements were recognized for posterity in 1992 with his election to the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Riggins was a 6-2, 240-pound workhorse who could always be depended upon for an all-out performance on the field. Fortunately or unfortunately, depending on the view point of those who were affected, his off- the-field antics were just as dependable -- they could be counted on to make the kind of news that tended to overshadow his excellent contributions as a player.