SUMMARY May 13, 2021 2021COA67 No. 19CA2040, Board

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colorado Fourteeners Checklist

Colorado Fourteeners Checklist Rank Mountain Peak Mountain Range Elevation Date Climbed 1 Mount Elbert Sawatch Range 14,440 ft 2 Mount Massive Sawatch Range 14,428 ft 3 Mount Harvard Sawatch Range 14,421 ft 4 Blanca Peak Sangre de Cristo Range 14,351 ft 5 La Plata Peak Sawatch Range 14,343 ft 6 Uncompahgre Peak San Juan Mountains 14,321 ft 7 Crestone Peak Sangre de Cristo Range 14,300 ft 8 Mount Lincoln Mosquito Range 14,293 ft 9 Castle Peak Elk Mountains 14,279 ft 10 Grays Peak Front Range 14,278 ft 11 Mount Antero Sawatch Range 14,276 ft 12 Torreys Peak Front Range 14,275 ft 13 Quandary Peak Mosquito Range 14,271 ft 14 Mount Evans Front Range 14,271 ft 15 Longs Peak Front Range 14,259 ft 16 Mount Wilson San Miguel Mountains 14,252 ft 17 Mount Shavano Sawatch Range 14,231 ft 18 Mount Princeton Sawatch Range 14,204 ft 19 Mount Belford Sawatch Range 14,203 ft 20 Crestone Needle Sangre de Cristo Range 14,203 ft 21 Mount Yale Sawatch Range 14,200 ft 22 Mount Bross Mosquito Range 14,178 ft 23 Kit Carson Mountain Sangre de Cristo Range 14,171 ft 24 Maroon Peak Elk Mountains 14,163 ft 25 Tabeguache Peak Sawatch Range 14,162 ft 26 Mount Oxford Collegiate Peaks 14,160 ft 27 Mount Sneffels Sneffels Range 14,158 ft 28 Mount Democrat Mosquito Range 14,155 ft 29 Capitol Peak Elk Mountains 14,137 ft 30 Pikes Peak Front Range 14,115 ft 31 Snowmass Mountain Elk Mountains 14,099 ft 32 Windom Peak Needle Mountains 14,093 ft 33 Mount Eolus San Juan Mountains 14,090 ft 34 Challenger Point Sangre de Cristo Range 14,087 ft 35 Mount Columbia Sawatch Range -

The Geologic Story of Colorado's Sangre De Cristo Range

The Geologic Story of Colorado’s Sangre de Cristo Range Circular 1349 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover shows a landscape carved by glaciers. Front cover, Crestone Peak on left and the three summits of Kit Carson Mountain on right. Back cover, Humboldt Peak on left and Crestone Needle on right. Photograph by the author looking south from Mt. Adams. The Geologic Story of Colorado’s Sangre de Cristo Range By David A. Lindsey A description of the rocks and landscapes of the Sangre de Cristo Range and the forces that formed them. Circular 1349 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2010 This and other USGS information products are available at http://store.usgs.gov/ U.S. Geological Survey Box 25286, Denver Federal Center Denver, CO 80225 To learn about the USGS and its information products visit http://www.usgs.gov/ 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Lindsey, D.A., 2010, The geologic story of Colorado’s Sangre de Cristo Range: U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1349, 14 p. iii Contents The Oldest Rocks ...........................................................................................................................................1 -

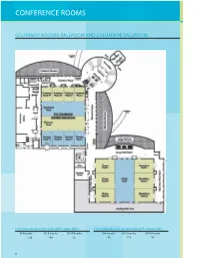

Conference Rooms

CONFERENCE ROOMS COLORADO ROCKIES BALLROOM AND COLUMBINE BALLROOM COLORADO ROCKIES EXHIBIT CAPACITIES COLUMBINE BALLROOM EXHIBIT CAPACITIES 8X8 booths 8X10 booths 10X10 booths 8X8 booths 8X10 booths 10X10 booths 120 104 92 150 125 100 6 CONFERENCE ROOMS WWW.KEYSTONECONFERENCES.COM CONFERENCE CENTER CENTER CONFERENCE Dining Square Dimensions Hollow Rounds of Footage LxWxH Theater Schoolroom Conference Square U-Shape Reception 12 people COLORADO ROCKIES BALLROOM 16000 157X102X18 1800 1100 X X X 1650 1620 CRESTONE OFFICE 40 4X10 X X X X X X X 2 SHAVANO OFFICE 80 4X20 X X X X X X X CHARTS CAPACITY / DIAGRAMS FLOOR CRESTONE PEAK 4000 38X102X18 480 275 X X X 400 360 CRESTONE I 1000 38X25X18 120 56 30 40 32 100 72 CRESTONE II 1000 38X25X18 120 56 30 40 32 100 72 CRESTONE III 1000 38X25X18 120 56 30 40 32 100 72 6 CRESTONE IV 1000 38X25X18 120 56 30 40 32 100 72 CRESTONE FOYER 1170 73X16X25 X X X X X 250 X SHIPPING PRICING/ VISUAL AUDIO CRESTONE TERRACE 1780 X X X X X X 250 180 RED CLOUD PEAK 4000 38X102X18 480 275 X X X 400 360 SHAVANO PEAK 4000 38X102X18 480 275 X X X 400 360 SHAVANO FOYER 2120 118X18X25 X X X X X 400 X 16 SHAVANO TERRACE 2100 110X19 X 25 X X X 150 200 TORREYS PEAK 4000 38X102X18 480 275 X X X 400 336 STANDARDS & POLICIES BANQUET MENUS/ TORREYS I 1000 38X25X18 120 56 30 40 32 100 72 TORREYS II 1000 38X25X18 120 56 30 40 32 100 72 TORREYS III 1000 38X25X18 120 56 30 40 32 100 72 TORREYS IV 1000 38X25X18 120 56 30 40 32 100 72 20 TORREYS FOYER 1530 102X15X25 X X X X X X X COLUMBINE BALLROOM 19800 120X165X18 2250 1275 X X X 2066 -

EVERYONE WHO HAS COMPLETED the COLORADO FOURTEENERS (In Order of Date of Submittal) ` First Name M.I

EVERYONE WHO HAS COMPLETED THE COLORADO FOURTEENERS (In Order of Date of Submittal) ` First Name M.I. Last Name First Peak Month Year Last Peak Month Year 1. Carl Blaurock (#1 & #2 tie) Pikes Peak 1911 1923 2. William F. Ervin (#1 & #2 tie) Pikes Peak 1911 1923 3. Albert Ellingwood 4. Mary Cronin Longs Peak 1921 Sep 1934 5. Carl Melzer 1937 6. Robert B. Melzer 1937 7. Elwyn Arps Eolus, Mt. 1920 Jul 1938 8. Joe Merhar Pyramid Peak Aug 1938 9. O. P. Settles Longs Peak 1927 Jul 1939 10. Harry Standley Elbert, Mt. 1923 Sep 1939 11. Whitney M. Borland Pikes Peak Jun 1941 12. Vera DeVries Longs Peak 1936 Kit Carson Peak Aug 1941 13. Robert M. Ormes Pikes Peak Capitol Peak Aug 1941 14. Jack Graham Sep 1941 15. John Ambler Sep 1943 16. Paul Gorham Pikes Peak 1926 Aug 1944 17. Ruth Gorham Grays Peak 1933 Aug 1944 18. Henry Buchtel Longs Peak 1946 19. Herb Hollister Longs Peak 1927 Jul 1947 20. Roy Murchison Longs Peak 1908 Aug 1947 21. Evelyn Runnette Longs Peak 1931 Uncompahgre Peak Sep 1947 22. Marian Rymer Longs Peak 1926 Crestones Sep 1948 23. Charles Rymer Longs Peak 1927 Crestones Sep 1948 24. Nancy E. Nones (Perkins) Quandary 1937 Eolus, Mt. Sep 1948 25. John Spradley Longs Peak 1943 Jul 1949 26. Eliot Moses Longs Peak 1921 Jul 1949 27. Elizabeth S. Cowles Lincoln, Mt. Sep 1932 Wetterhorn Peak Sep 1949 28. Dorothy Swartz Crestones Aug 1950 29. Robert Swartz Bross, Mt. 1941 Crestones Aug 1950 30. -

July 9, 2020 BOA Meeting Agenda

CITY OF BRIGHTON REGULAR MEETING OF THE BOARD OF ADJUSTMENT AGENDA July 9, 2020 Meeting is to be held virtually at https://brightonco.cc/38m0Hwp To join by telephone (for higher quality, dial a number based on your current location): 1-669-900-9128, 1-253-215-8782, 1-346-248-7799, 1-646-558-8656, 1-301-715-8592, 1-312-626-6799 Webinar ID: 849 4346 5666 Chairman: Chris Maslanik Ward III Vice-Chair: Fidel Balderas At Large Commissioners: Oliver Shaw Ward I William Leck Ward IV Vacant Ward II Liane Wahl Alternate John Morse Alternate Giana Rocha Youth Stephen Colvin Youth ATTENTION TO ALL ATTENDING PUBLIC HEARING Please leave all cell phones out of the Commission Chambers or make sure that they are turned off before entering. Thank You! Por favor apage todos telefonos de celular y aparatos de busca personas antes de entrar al concejo municipal. Muchas Gracias! I. Call to Order immediately following the Planning Commission meeting II. Pledge of Allegiance III. Roll Call IV. Minutes from the October 10, 2019 BOA meeting will be presented for approval V. Public invited to be heard on items not on the agenda VI. Agenda Items 1. Variance request for water tower at 4204 Crestone Peak Street: Nick Di Mario presenting VII. Old Business VIII. New Business IX. Reports X. Adjournment CITY OF BRIGHTON BOARD OF ADJUSTMENT MINUTES October 10, 2019 I. CALL TO ORDER Chairman Maslanik called the meeting to order at 7:57 p.m. II. ROLL CALL Roll call was taken with the following Commissioners in attendance: Chris Maslanik, Oliver Shaw, Fidel Balderas and Rex Bell. -

Special Work Sessions

BOARD OF COUNTY COMMISSIONERS OF RIO BLANCO COUNTY, COLORADO Monday, June 3, 2019 Tuesday, June 4, 2019 Wednesday, June 5, 2019 SPECIAL WORK SESSIONS WHEN: Monday, June 3, 2019 Tuesday, June 4, 2019 Wednesday, June 5, 2019 WHERE: The Keystone Resort 21966 Highway 6 Keystone, CO 80435 TOPIC: CCI is a non-profit, membership association whose purpose is to offer assistance to county commissioners, mayors and council members and to encourage counties to work together on common issues. Governed by a board of directors consisting of eight commissioners from across the state, our focus is on information, education and legislative representation. We strive to keep our members up-to-date on issues that directly impact county operations. At the same time, we work to present a united voice to the Colorado General Assembly and other government and regulatory bodies to help shape the future. NOTE: One or more Commissioner may attend one or more of the meetings together. Please the attached Agenda for the CCI Work Shops. 2019 Summer Conference - Schedule at a Glance Monday, June 3, 2019 9 am – Noon Child Welfare Allocation Committee (CWAC) Crestone Peak 2-3 1 pm – 6 pm Registration Desk Open - Sponsored by Honnen Equipment Conference Center Lobby 1 pm – 5 pm Works Allocation Committee (WAC) Crestone Peak 2-3 1:30 pm – 3 pm CCI Issue Session | Ground Ambulance Licensing – A County Commissioner Responsibility Toreys Peak 2 1:30 pm – 3:30 pm New Commissioner Potpourri Toreys Peak 1 1:30 pm – 5 pm ACCA Issue Session | High Performance Governance – Bridging -

Timberline 1 Letter from the CEO Celebrating in Style

HigHer tHan everest 16 • make it spiritual 28 • tHe fourteeners and beyond 36 Trail & TThe Coloradoimberline Mountain Club • Winter 2011 • Issue 1013 • www.cmc.org Rocky Mountain HigH Trail & Timberline 1 Letter from the CEO Celebrating in Style n October 1, the CmC officially Climbs, and ryan ross is helping to put on launched its 100th year anniver- a majority of the events throughout the year. sary. i’m pleased to announce Thank you! Owe’ve dramatically expanded our plans to Registration for the first two events is celebrate the club’s milestone. We’re going open now at www.cmc.org/centennial. See to hold a series of “big-tent” events to better the entire calendar of events on page 6. take advantage of this once-in-a-century op- I look forward to seeing you at as many portunity to honor our history, drive fund- of these events as you can attend. One thing raising, increase membership, and celebrate i know for certain: We will end our centen- in style. Here’s your chance to be a part of nial year knowing we did everything we club history. could to celebrate this once-a-century mile- We’ve got a star-studded lineup to help stone in style. us celebrate, including a few local celebri- Happy 100th, CmC! ties. none of this would be possible with- out the help of a few committed and hard working volunteers. Our 100th anniversary Committee is comprised of linda lawson, Giles Toll, Steve bonowski, al Ossinger, Katie Blackett John Devitt, and bob reimann. -

Difficulty4 Fourteener Name Elev in Feet Trails Illust Map USGS 7.5

Fourteener Elev in Trails Illust USGS Lat Long Dist3 Vert3 Difficulty4 Name Feet Map 7.5' Topo (RT) Gain Grade Class Antero, Mt 14,269 130 E Mt Antero & St Elmo 38° 40' 106° 15' 13 5200 C 2 Belford, Mt 14,197 129 W Mt Harvard 38° 58' 106° 22' 7 4500 B 2 Bierstadt, Mt 14,060 104 E Mt Evans 39° 35' 105° 40' 6.5 2800 A 2 Blanca Peak 14,345 138 S Blanca Peak & Twin Peaks 37° 35' 105° 29' 14 5000 D 2 Bross, Mt 14,172 109 E Alma 39° 20' 106° 06' 5 2900 A 2 Cameron, Mt2 14,238 109 E Alma 39° 21' 106° 07' 4.5 3000 A 2 Capitol Peak 14,130 128 E Capitol Peak 39° 09' 107° 05' 15 4800 D 3 E Castle Peak 14,265 127 W Hayden Peak 39° 01' 106° 52' 10 4400 C 2 Challenger Point2 14,081 138 S Crestone Peak 37° 59' 105° 36' 10 5400 C 3 Columbia, Mt 14,073 129 W Mt Harvard 38° 54' 106° 18' 11 4100 C 2 Conundrum Peak2 14,022 127 W Hayden Peak 39° 01' 106° 52' 10 4200 C 3 Crestone Needle 14,197 138 S Crestone Peak 37° 58' 105° 35' 18 5400 D 3 E Crestone Peak 14,294 138 S Crestone Peak 37° 58' 105° 35' 20 6700 D 3 E Culebra Peak 14,047 N/A Culebra Peak & El Valle Creek 37° 07' 105° 11' 4 2500 A 2 Democrat, Mt 14,148 109 W Climax & Alma 39° 20' 106° 08' 7 3500 B 2 El Diente Peak 14,159 141 W Delores Peak & Mt Wilson 37° 50' 108° 00' 13.5 4800 D 3 Elbert, Mt 14,433 127 E Mt Elbert & Mt Massive 39° 07' 106° 27' 8.5 4700 C 1 Ellingwood Point 14,042 138 S Blanca Peak & Twin Peaks 37° 35' 105° 30' 13.5 4700 D 3 Eolus, Mt 14,083 140 W Columbine Pass & Mnt View Crest 37° 37' 107° 37' 18.5 6000 D 3 Evans, Mt 14,264 104 E Mt Evans 39° 35' 105° 39' 1 1500 A 2 Grays Peak -

Estimated Hiking Use on Colorado's 14Ers

Estimated Hiking Use on Colorado’s 14ers Total Hiker Use Days: 415,000 (2020 Data) Front Range Best Est: 113,500 Mosquito Range Best Est: 49,000 Longs Peak 15,000-20,000^ Mount Lincoln 25,000-30,000* Pikes Peak 15,000-20,000* Mount Bross Torreys Peak 30,000-35,000* Mount Democrat Grays Peak Mount Sherman 15,000-20,000* Mount Evans 7,000-10,000 Mount Bierstadt 35,000-40,000* Elk Mountains Best Est: 11,500 Castle Peak 3,000-5,000* Tenmile Range Best Est: 49,000 Maroon Peak 1,000-3,000 Quandary Peak 45,000-50,000* Capitol Peak 1,000-3,000 Snowmass Mountain 1,000-3,000 Pyramid Peak 1,000-3,000 Sawatch Range Best Est: 110,000 Mount Elbert 20,000-25,000* Mount Massive 7,000-10,000 Sangre de Cristo Range Best Est: 13,000 Mount Harvard 5,000-7,000 Blanca Peak 1,000-3,000* La Plata Peak 5,000-7,000* Ellingwood Point Mount Antero 3,000-5,000 Crestone Peak 1,000-3,000 Mount Shavano 7,000-10,000 Crestone Needle 1,000-3,000 Tabegauche Peak Kit Carson Peak 1,000-3,000 Mount Belford 7,000-10,000 Challenger Point Mount Oxford Humboldt Peak 1,000-3,000 Mount Princeton 7,000-10,000* Culebra Peak <1,000 Mount Yale 7,000-10,000 Mount Lindsey 1,000-3,000* Mount Columbia 3,000-5,000 Little Bear Peak 1,000-3,000 Missouri Mountain 5,000-7,000 Mt. -

Estimated Hiking Use on Colorado's 14Ers

Estimated Hiking Use on Colorado’s 14ers Total Hiker Use Days: 353,000 (2018 Data) Front Range Best Est: 107,000 Mosquito Range Best Est: 39,000 Longs Peak 15,000-20,000 Mount Lincoln 20,000-25,000* Pikes Peak 10,000-15,000* Mount Bross Torreys Peak 25,000-30,000* Mount Democrat Grays Peak Mount Sherman 15,000-20,000* Mount Evans 10,000-15,000 Mount Bierstadt 35,000-40,000# Elk Mountains Best Est: 9,000 Castle Peak 1,000-3,000* Tenmile Range Best Est: 38,000 Maroon Peak 1,000-3,000 Quandary Peak 35,000-40,000* Capitol Peak 1,000-3,000 Snowmass Mountain 1,000-3,000 Pyramid Peak 1,000-3,000 Sawatch Range Best Est: 98,000 Mount Elbert 20,000-25,000* Mount Massive 7,000-10,000^ Sangre de Cristo Range Best Est: 17,000 Mount Harvard 5,000-7,000^ Blanca Peak 1,000-3,000* La Plata Peak 5,000-7,000* Ellingwood Point Mount Antero 3,000-5,000 Crestone Peak 1,000-3,000 Mount Shavano 5,000-7,000 Crestone Needle 1,000-3,000 Tabegauche Peak Kit Carson Peak 1,000-3,000 Mount Belford 7,000-10,000^ Challenger Point Mount Oxford Humboldt Peak 3,000-5,000 Mount Princeton 5,000-7,000 Culebra Peak 1,000-3,000 Mount Yale 7,000-10,000^ Mount Lindsey 1,000-3,000* Mount Columbia 3,000-5,000^ Little Bear Peak 1,000-3,000 Missouri Mountain 3,000-5,000^ Mt. -

Flat 14Ers Individual Progress Log

Flat 14ers Individual Progress Log Name: Start Date: Completion Date: Peak: Distance: Elevation: Steps: 1 Blanca Peak 15 miles 14,345 ft 30,000 2 Capitol Peak 17 miles 14,130 ft 34,000 3 Castle Peak / Conundrum Peak* 14 miles 14,265 ft / 14,060 ft 28,000 4 Challenger Point 12 miles 14,081 ft 24,000 5 Crestone Needle 8 miles 14,197 ft 16,000 6 Crestone Peak 6.25 miles 14,294 ft 12,500 7 Culebra Peak 7 miles 14,047 ft 14,000 8 Ellingood Point 15.5 miles 14,042 ft 31,000 9 Grays Peak 7.5 miles 14,270 ft 15,000 10 Handies Peak 5.5 miles 14,048 ft 11,000 11 Humbolt Peak 7.25 miles 14,064 ft 14,500 12 Huron Peak 5.5 miles 14,003 ft 11,000 13 Kit Carson Peak 11.5 miles 14,165 ft 23,000 14 La Plata Peak 9.5 miles 14,336 ft 19,000 15 Little Bear Peak 13 miles 14,037 ft 26,000 16 Longs Peak 14 miles 14,255 ft 28,000 17 Maroon Peak / North Maroon Peak* 12 miles 14,156 ft /14,014 ft 24,000 18 Missouri Mountain 10.5 miles 14,067 ft 21,000 19 Mt Antero 13.6 miles 14,269 ft 27,000 20 Mt Belford 11 miles 14,197 ft 22,000 21 Mt Bierstadt 7 miles 14,060 ft 14,000 22 Mt Bross 9 miles 14,172 ft 18,000 23 Mt Columbia 11.5 miles 14,073 ft 23,000 24 Mt Democrat 4 miles 14,148 ft 8,000 25 Mt Elbert 9 miles 14,433 ft 18,000 www.americaonthemove.org ©2009 America On the Move Foundation, Inc. -

CRESTONE PEAK RESOURCES OPERATING LLC FINAL CDP SUBMISSION DATE: June 15, 2018 COGCC REQUESTED INFORMATION

CRESTONE PEAK RESOURCES OPERATING LLC FINAL CDP SUBMISSION DATE: June 15, 2018 COGCC REQUESTED INFORMATION BEFORE THE OIL AND GAS CONSERVATION COMMISSION OF THE STATE OF COLORADO IN THE MATTER OF THE APPLICATION OF CAUSE NO. 1 CRESTONE PEAK RESOURCES OPERATING LLC FOR AN ORDER TO ESTABLISH AND APPROVE A RULE 216 COMPREHENSIVE DRILLING PLAN DOCKET NO. 170500189 FOR PORTIONS OF SECTIONS 1, 2, 3, 10, 11 AND 12, TOWNSHIP 1 NORTH, RANGE 69 WEST, 6th P.M. AND PORTIONS OF SECTIONS 25, 26, 27, 34, TYPE: GENERAL ADMINISTRATIVE 35 AND 36, TOWNSHIP 2 NORTH, RANGE 69 WEST, 6TH P.M. FOR THE COMPREHENSIVE DEVELOPMENT AND OPERATION OF THE CODELL AND NIOBRARA FORMATIONS, WATTENBERG FIELD, BOULDER COUNTY, COLORADO. CRESTONE PEAK RESOURCES OPERATING LLC’S FINAL COMPREHENSIVE DRILLING PLAN CONTAINING ALL CONCEPTUAL, PRELIMINARY AND FINAL CDP PLAN ELEMENTS Pursuant to the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission’s (“Commission”) Comprehensive Drilling Plan (“CDP”) Pre-Hearing Application Process and Timeline (“Process”)1, Crestone Peak Resources Operating LLC (“Crestone”), by and through its undersigned attorneys, hereby submits the following Final Comprehensive Drilling Plan containing all Conceptual, Preliminary and Final CDP Plan Elements (the “Final CDP”) at the request of the Commission2. Pursuant to the Commission process established for Crestone’s Rule 216 CDP Application, as amended, if this Final CDP is satisfactory to Commission Staff, the Commission Director will file a hearing application with the full Commission requesting acceptance of the CDP and schedule a hearing for September 17-18, 2018.3 Executive SummAry of FinAl CDP Crestone filed its application to establish and approve a voluntary Rule 216 Comprehensive Drilling Plan for the CDP Area (defined below) on February 22, 2017.